|

SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN COURT |

| << INTERPERSONAL POWER: LEADERSHIP, The Situational Perspective, Information power |

| SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN CLINIC >> |

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Lesson

43

SOCIAL

PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL

PSYCHOLOGY IN COURT

Aims:

·

To

understand the use of social psychology theories and

principles in court and legal

settings

Objectives:

·

To

discuss the persuasiveness of eyewitness

testimony.

·

To

describe other factors affecting

juror's judgments

Section

V: Social Psychology

Applied

Social

Psychology Applied is not a

separate section as far as syllabus of

social psychology is concerned.

Instead

it is based on the theories and

principles of social psychology

that we have studied so far

in

different

sections of our syllabus,

for example, person

perception, attitude formation,

persuasion,

interpersonal

interactions, and so on. Although

knowledge of social psychology

can be applied in a

variety

of

social settings, and fields of human

interaction, we will specially

discuss two areas where

this

knowledge

is very effectively

applied:

·

Social

Psychology in Clinics

·

Social

Psychology in court

Social

Psychology in Court

Chapter

Summary

This

chapter focuses on social psychological

aspects of the legal system.

The lecture begins with

an

examination

of research on eyewitness identification. Eyewitness

identifications are frequently

inaccurate.

Two

categories of variables that

influence these identifications

are estimator variables, which

concern the

eyewitness

and the situation (for example,

viewing conditions, arousal, weapon focus, own-race

bias, and

retention

interval) and system variables

under control of the legal

system, for example,

suggestive

questioning

and lineup procedures. Factors

that make for optimal eyewitness

identification are

identified.

The

conditions under which false

confessions occur, and under

which people may come to

believe their

own

false confessions, are examined.

Other factors that influence

juror decision making,

including

defendant

characteristics (like attractiveness

and race), and similarity to

jury are reviewed.

Introduction

Several

questions interest social psychologists working in

court setting, for example,

how influential is

eyewitness

testimony? How trustworthy

are eyewitness recollections? What

makes a credible

witness?

Such

questions fascinate lawyers, judges, and defendants.

And they are questions to

which social

psychology

can suggest answers, as most

law schools have recognized when

they hire professors of

"law

and

social science." There is a long list of

topics pertinent to both social

psychology and law. For

example:

·

How do

a culture's norms and traditions

influence its legal

decisions?

·

What

legal procedures strike

people as fair? How

important are perceptions of the judge's

or

mediator's

neutrality and honesty?

·

How do

we, and should we, attribute

responsibility of a crime to the

defendant?

Studying

the legal system helps social psychologists

see how behavior occurs in

complex, personally

relevant,

and emotion-laden contests.

·Two heavily researched

sets of factors :

Features of the courtroom

drama that can influence

jurors' judgments of a

defendant

Characteristics of both the jurors

and their

deliberations.

Although

many aspects of court and

legal system are of interest to

social psychologists, we will be

just

discussing

two main topics due to shortage of

time and space:

o

Eyewitness

testimony, and

o

Other

influences on judgment of

jury.

185

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Eyewitness

testimony: Persuasiveness

Several

studies have indicated that eyewitness

testimony is very persuasive. At the

University of

Washington,

Elizabeth Loftus (1974,

1979) found that those

who had "seen" were indeed

believed, even

when

their testimony was shown to be

useless. When students were

presented with a hypothetical

robbery-

murder

case with circumstantial evidence

but no eyewitness testimony, only

18% voted for

conviction.

Other

students received the same

information but with the

addition of a single eyewitness and

72% voted

for

conviction. For a third

group, the defense attorney

discredited this testimony

(the witness's eye sight

was

weak and was not wearing

glasses). Did this

discrediting reduce the effect of the

testimony? In this

case,

not much: 68% still voted

for conviction.

Later

experiments revealed that discrediting

may reduce somewhat the number of

guilty votes. But

unless

contradicted

by another eyewitness, a vivid eyewitness account is

difficult to erase from

jurors' minds. That

helps

explain why; compared to

criminal cases lacking those

that have eyewitness testimony are

more

likely

to produce convictions.

How

accurate are eyewitnesses?

The

persuasiveness of eyewitness leads us to a

very important question and

that is the accuracy of

eyewitness

testimony. Is eyewitness testimony, in

fact, often inaccurate? Stories

abound of innocent

people

who

have wasted years in prison

because of the testimony of eyewitnesses

who were sincerely

wrong.

More

than seven decades ago, Yale

law professor Edwin Borchard

(1932) documented 65 convictions

of

people

whose innocence was later

proven. Most resulted from mistaken

identifications.

To

assess the accuracy of eyewitness

recollections, we need to learn

their overall rates of

"hits" and

"misses."

One way to gather such

information is to stage crimes comparable

to those in everyday life

and

then

solicit eyewitness reports. This has

now been done many times,

sometimes with disconcerting

results.

For

example, at the California State

University-Hay ward, 141

students witnessed an "assault" on

a

professor.

Seven weeks later, when

Robert Buckhout (1974) asked

them to identify the assailant from

a

group

of six photographs, 60% chose an

innocent person. No wonder

eyewitnesses to actual crimes

sometimes

disagree about what they

saw. Later studies have confirmed

that eyewitnesses often are

more

confident

than correct. For example,

Brian Born-stein and Douglas

Zickafoose (1999) found that

students

averaged

74% confident in their later

recollections of a classroom visitor,

but were only 55%

correct.

Factors

affecting eyewitness testimony

Stress

and Arousal

Stress increases memory

for the event itself but

decreases memory for what

preceded and followed

the

incident.

Weapon

Focus Effect

People tend to keep their eye on

weapons because of their danger

and novelty.

This distracts their

attention from the robbers.

Own-Race

Bias

People are more accurate in

identifying members of their

own race.

Retention

Interval

Accuracy drops with

time rapidly at first, then

levels off.

Suggestive

Questioning

The

way witnesses are questioned

influences their memories of the

event.

Some questions are suggestive

but not deliberately

misleading

·E.g. Loftus & Palmer

(1978) found that people

said a car had been going

faster in an accident if they

asked

about

its speed when it "smashed"

into the other car as

opposed to "hit" it

Other questions are

deliberately misleading, asking

about nonexistent

details.

186

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

·

Identification

procedures:

Show-ups

ask witnesses to indicate

whether or not a single witness is the

perpetrator

Simultaneous

lineups

Show the witness several potential

suspects at the same

time.

Sequential

lineups

Show potential suspects

one at a time; this approach

has been proved

effective.

Three

hypotheses for how

post-event information affects

memory

over-writing

forgetting

source monitoring

People

retain memories of both the

event and any post-event information

but cannot identify the source

of

the

memories. Evidence supports

this technique.

Reducing

Error in eyewitness

testimony

Train

police interviewers:

When

Ronald Fisher and his co-workers

(1987) examined tape-recorded interviews

of eyewitnesses

conducted

by experienced Florida police detectives,

they found a typical

pattern. Following an open-ended

beginning

("Tell me what you recall"),

the detectives would occasionally

interrupt with

follow-up

questions,

including questions eliciting terse

answers ("How tall was

he?"). Fisher and Edward

Geiselman

(1996)

and the new guide book say

interviews should begin by

allowing eyewitnesses to offer

their own

unprompted

recollections.

The

recollections will be most complete if

the interviewer jogs the memory by

first guiding people

to

reconstruct

the setting. Have them visualize the

scene and what they were

thinking and feeling at the

time.

Even

showing pictures of the setting--of, say, the

store checkout lane with a

clerk standing where she

was

robbed--can

promote accurate recall

(Cutler & Penrod, 1988). After

giving witnesses ample,

uninterrupted

time

to report everything that

comes to mind, the interviewer

then jogs their memory

with evocative

questions

("Was there anything unusual about the

voice? Was there anything unusual

about the person's

appearance

or clothing?"). In this reference, Ronald

Fisher et al. (1987) suggested

that allow

eyewitnesses

to

offer their own unprompted

recollections and ask questions. People

may be guided to reconstruct the

setting

for better recall (Cutler

& Penrod, 1988). A statistical

summary of 42 studies confirmed

that the

"cognitive

interview" substantially increase

details recalled, with no

loss in accuracy (Kohnken et

al.,

1999).

Minimize

false lineup identification:

Instructions

given to eyewitnesses are

also important. Identifications

are most accurate when the

witness is

told

that the suspect "may or may

not" be in the lineup. Another

useful strategy is that give a

blank lineup

to

the identifiers which contains no

suspects, and screens those

who make false

identifications.

Educate

jurors:

·

If the

facts of a case are

compelling, then jury can

lay aside their biases

and render a fair

judgment.

·

However,

studies conducted in several countries show that

jurors discount most of the

factors

which

are known to influence eyewitness

testimony

·

A

survey of 63 experts on eyewitness testimony

lists the most agreed-upon phenomena to

help

jurors

evaluate the testimony of both

prosecution and defense witness:

o

Question

wording:

An

eyewitness's testimony can be affected by

how the questions are

asked.

o

Lineup

instructions

o

Post-event

information:

187

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Eyewitness

testimony is not only

affected by what they

actually saw but

information

they obtained later

on.

Accuracy

vs. confidence

o

An

eyewitness's confidence may not be a

good predictor.

Attitudes

and expectation:

o

Eyewitness's

perception and memory of an event

may be affected by

his

attitudes.

Other

influences on Judgments

Physical

attractiveness

o

We

have seen (in chapters of

person perception and persuasion) that

communicators are more

persuasive

if they seem credible and

attractive. How jurors and judges

make social judgments?

Michael

Efran (1974) asked students

whether attractiveness should affect

presumption of guilt.

o

The

answer was, "No, it

shouldn't". But did it?

When Efran gave other

students a description

of

the case with a photograph of

either an attractive or an unattractive

defendant, they

judged

the

most attractive as less

guilty and recommended that

person for the least

punishment.

Many

experiments and field studies have supported

these results.

o

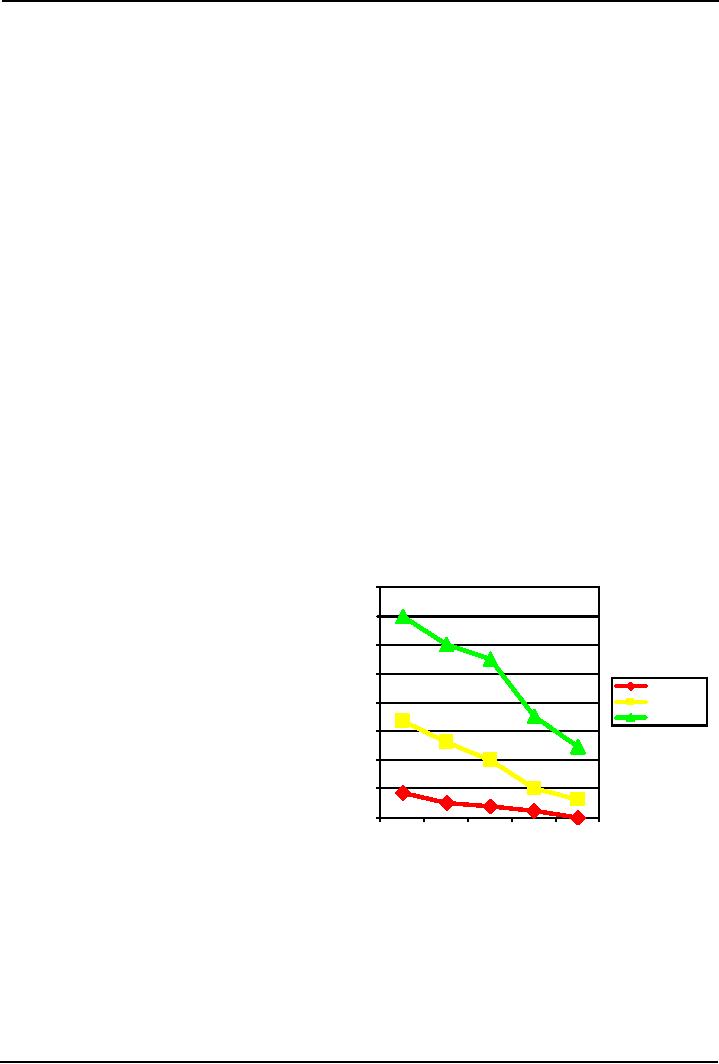

An

example of the real world phenomenon is

Chris Downs and Lyons's

study (1991). They

o

asked

police escorts to rate the physical

attractiveness of 1,742 defendants appearing

before 40

judges

in misdemeanour cases. The results shown

in Figure 1 indicate that the judges

set

higher

bails and fines for less

attractive defendants:

Figure

1: Attractiveness and legal judgments for

minor, moderate and serious

crimes

Similarity

to the jurors

16

0 0

·Jurors are

more

sympathetic to a defendant

14

0 0

who

shares their attitudes,

religion, race, or

gender

(Selby et al., 1977)

12

0 0

English speaking people more

likely to think

10

0 0

the

person not guilty if the

defendant's

M

ino r

testimony

was in English rather than

translated

800

M

o de ra t e

S

e rio us

form

Spanish or Thai (Stephen &

Stephen,

600

1986).

400

·Similar

prejudice

has been reported in

200

psychiatry.

0

1

2

3

4

5

Readings:

·

David

G. Myers, D. G. (2002).

Social

Psychology

(7th ed.). New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Taylor,

S.E. (2006). Social

Psychology (12th ed.). New York: Prentice

Hall.

·

188

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Readings, Main Elements of Definitions

- INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Social Psychology and Sociology

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Scientific Method

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Evaluate Ethics

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY RESEARCH PROCESS, DESIGNS AND METHODS (CONTINUED)

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY OBSERVATIONAL METHOD

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY CORRELATIONAL METHOD:

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY EXPERIMENTAL METHOD

- THE SELF:Meta Analysis, THE INTERNET, BRAIN-IMAGING TECHNIQUES

- THE SELF (CONTINUED):Development of Self awareness, SELF REGULATION

- THE SELF (CONTINUE…….):Journal Activity, POSSIBLE HISTORICAL EFFECTS

- THE SELF (CONTINUE……….):SELF-SCHEMAS, SELF-COMPLEXITY

- PERSON PERCEPTION:Impression Formation, Facial Expressions

- PERSON PERCEPTION (CONTINUE…..):GENDER SOCIALIZATION, Integrating Impressions

- PERSON PERCEPTION: WHEN PERSON PERCEPTION IS MOST CHALLENGING

- ATTRIBUTION:The locus of causality, Stability & Controllability

- ATTRIBUTION ERRORS:Biases in Attribution, Cultural differences

- SOCIAL COGNITION:We are categorizing creatures, Developing Schemas

- SOCIAL COGNITION (CONTINUE…….):Counterfactual Thinking, Confirmation bias

- ATTITUDES:Affective component, Behavioral component, Cognitive component

- ATTITUDE FORMATION:Classical conditioning, Subliminal conditioning

- ATTITUDE AND BEHAVIOR:Theory of planned behavior, Attitude strength

- ATTITUDE CHANGE:Factors affecting dissonance, Likeability

- ATTITUDE CHANGE (CONTINUE……….):Attitudinal Inoculation, Audience Variables

- PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION:Activity on Cognitive Dissonance, Categorization

- PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION (CONTINUE……….):Religion, Stereotype threat

- REDUCING PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION:The contact hypothesis

- INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION:Reasons for affiliation, Theory of Social exchange

- INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION (CONTINUE……..):Physical attractiveness

- INTIMATE RELATIONSHIPS:Applied Social Psychology Lab

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE:Attachment styles & Friendship, SOCIAL INTERACTIONS

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE (CONTINE………):Normative influence, Informational influence

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE (CONTINUE……):Crimes of Obedience, Predictions

- AGGRESSION:Identifying Aggression, Instrumental aggression

- AGGRESSION (CONTINUE……):The Cognitive-Neo-associationist Model

- REDUCING AGGRESSION:Punishment, Incompatible response strategy

- PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR:Types of Helping, Reciprocal helping, Norm of responsibility

- PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE………):Bystander Intervention, Diffusion of responsibility

- GROUP BEHAVIOR:Applied Social Psychology Lab, Basic Features of Groups

- GROUP BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE…………):Social Loafing, Deindividuation

- up Decision GROUP BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE……….):GroProcess, Group Polarization

- INTERPERSONAL POWER: LEADERSHIP, The Situational Perspective, Information power

- SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN COURT

- SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN CLINIC

- FINAL REVIEW:Social Psychology and related fields, History, Social cognition