|

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

LESSON

33

PRICING

AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.)

BROAD

CONTENTS

Materials/Support

Costs

Pricing

out the Work

System

Pricing

Developing

the Supporting/Backup Costs

The

Low-Bidder Dilemma

Special

Problems

Estimating

Pitfalls

33.1

MATERIALS/SUPPORT

COSTS:

Three

of four major pricing input

requirements are fulfilled by the salary structure,

overhead

structure,

and labor hours. The fourth

major input is the cost for

materials and support. Six

subtopics

are included under

materials/support: materials, purchased

parts, subcontracts,

freight,

travel,

and other. Freight and travel

can be handled in one of two

ways, both normally

dependent

on the size of the program. For

small-dollar-volume programs, estimates

are made

for

travel and freight. For

large dollar-volume programs, travel is

normally expressed as

between

3 and 5 percent of the direct labor

costs, and freight is

likewise between 3 and 5

percent

of all costs for material,

purchased parts, and subcontracts.

The category labeled

"other

support

costs" may include such

topics as computer hours or special consultants.

Determination

of the material costs is very

time-consuming, more so than cost

determination for

labor

hours. Material costs are

submitted via a bill of materials

that includes all vendors

from

whom

purchases will be made,

projected costs throughout the

program, scrap factors, and

shelf

lifetime

for those products that may

be perishable.

As

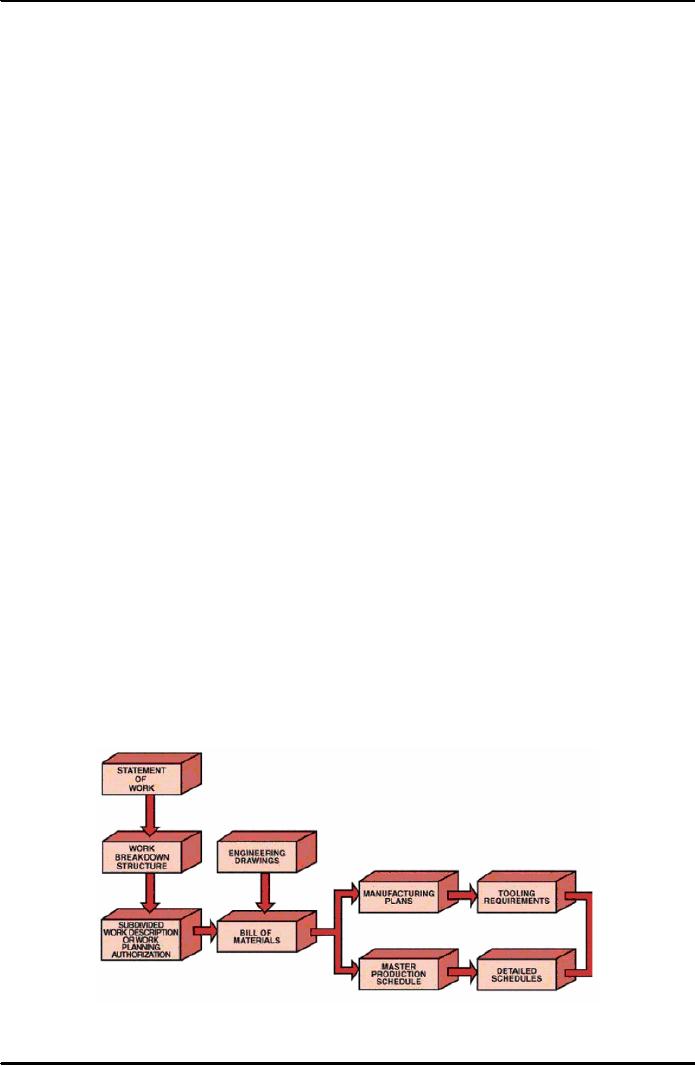

depicted in the Figure 33.1

below, upon release of the

work statement, work

breakdown

structure,

and subdivided work description, the

end-item bill of materials and

manufacturing

plans

are prepared. End item materials

are those items identified as an

integral part of the

production

end-item. Support materials consist of

those materials required by engineering

and

operations

to support the manufacture of end-items, and are

identified on the manufacturing

plan.

Figure

33.1: Material

Planning Flow Chart

239

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

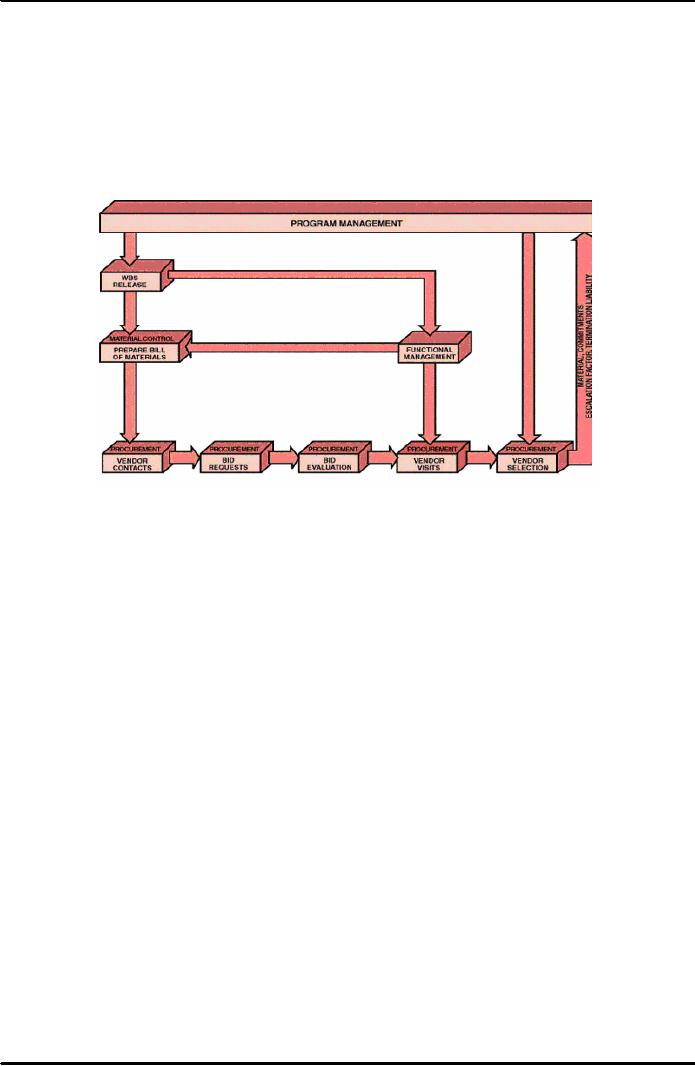

Furthermore,

a procurement plan/purchase requisition is prepared as

soon as possible after

contract

negotiations (using a methodology as

shown in Figure 33.2 below).

This plan is used to

monitor

material acquisitions, forecast

inventory levels, and

identify material price

variances.

Manufacturing

plans prepared upon release of the

subdivided work descriptions are

used to

prepare

tool lists for

manufacturing, quality assurance,

and engineering. From these

plans a

special

tooling breakdown is prepared by tool

engineering, which defines

those tools to be

procured

and the material requirements of tools to

be fabricated in-house. These items

are

priced

by cost element for input on the

planning charts.

Figure

33.2: Procurement

Activity

The

materials/support costs are

submitted by month for each

month of the program. If

long-lead

funding

of materials is anticipated, then they

should be as items must be applied to

all

materials/support

costs. Some vendors may

provide fixed prices over

time periods in excess of

a

twelve-month

period. As an example, vendor Z

may quote a firm-fixed price

of $130.50 per unit

for

650 units to be delivered

over the next eighteen

months if the order is placed within

sixty

days.

There are additional factors

that influence the cost of

materials.

33.2

PRICING

OUT THE WORK:

Note

that the logical pricing techniques

are available in order to

obtain detailed estimates.

The

following

thirteen steps provide a

logical sequence in order to

better control the

company's

limited

resources. These steps may

vary from company to

company.

Step

1: Provide

a complete definition of the work

Step

2: Establish a

logic network with

checkpoints.

Step

3: Develop

the work breakdown structure.

Step

4: Price

out the work breakdown

structure.

Step

5: Review

WBS costs with each

functional manager.

Step

6: Decide

on the basic course of

action.

Step

7: Establish

reasonable costs for each

WBS element.

Step

8: Review

the base case costs with

upper-level management.

Step

9: Negotiate

with functional managers for

qualified personnel.

Step

10: Develop

the linear responsibility chart.

Step

11: Develop

the final detailed and PERT/CPM

schedules.

Step

12: Establish

pricing cost summary reports.

Step

13: Document the

result in a program

plan.

240

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

Although

the pricing of a project is an iterative

process, the project manager

must still burden

himself

at each iteration point by

developing cost summary reports so

that key project

decisions

can

be made during the planning.

Detailed pricing summaries

are needed at least twice:

in

preparation

for the pricing review

meeting with management and at

pricing termination. At

all

other

times it is possible that ''simple

cosmetic surgery" can be

performed on previous

cost

summaries,

such as perturbations in escalation factors

and procurement cost of raw

materials.

The

list identified below shows

the typical pricing reports:

·

A

detailed cost breakdown for

each Work Breakdown Structure

(WBS) element. If the

work

is

priced out at the task

level, then there should be a

cost summary sheet for each

task, as

well

as rollup sheets for each

project and the total

program.

·

A

total program manpower curve

for each department. These

manpower curves show how

each

department has contracted with the

project office to supply

functional resources. If the

departmental

manpower curves contain several "peaks and

valleys," then the

project

manager

may have to alter some of

his schedules to obtain some

degree of manpower

smoothing.

Functional managers always

prefer manpower-smoothed resource

allocations.

·

A

monthly equivalent manpower

cost summary. This

table normally shows the

fully

burdened

cost for the average

departmental employee carried

out over the entire period

of

project

performance. If project costs have to be reduced, the

project manager performs a

parametric

study between this table and the manpower

curve tables.

·

A

yearly cost distribution

table. This

table is broken down by WBS

element and shows the

yearly

(or quarterly) costs that

will be required. This

table, in essence, is a project

cash-flow

summary

per activity.

·

A

functional cost and hour

summary. This

table provides top

management with an

overall

description

of how many hours and dollars

will be spent by each major

functional unit, such

as

a division. Top management

would use this as part of

the forward planning process

to

make

sure that there are

sufficient resources available

for all projects. This also

includes

indirect

hours and dollars.

·

Monthly

labor hour and dollar

expenditure forecast. This

table can be combined with

the

yearly

cost distribution, except that it is

broken down by month, not

activity or department.

In

addition, this table

normally includes manpower termination

liability information

for

premature

cancellation of the project by outside

customers.

·

A

raw material and expenditure

forecast. This

shows the cash flow for

raw materials based

on

vendor lead times, payment

schedules, commitments, and termination

liability.

·

Total

program termination liability

per month. This

table shows the customer the

monthly

costs

for the entire program. This

is the customer's cash flow,

not the contractor's. The

difference

is that each monthly cost

contains the termination liability for

man-hours and

dollars,

on labor and raw materials. This

table is actually the monthly

costs attributed to

premature

project termination.

It

is important to note that

these tables are used by

both project managers and

upper-level

executives.

The project managers utilize

these tables as the basis

for project cost control.

Top-

level

management utilizes them for selecting,

approving, and prioritizing

projects.

33.3

SYSTEMS

PRICING:

The

basis of successful program

management is the establishment of an accurate

cost package

from

which all members of the

organization can both

project and track costs. The

cost data must

241

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

be

represented in such a manner

that maximum allocation of the corporate

resources of people,

money,

and facilities can be achieved.

In

addition, the systems approach to pricing

out the activity schedules

and the work

breakdown

structure

provides a means for

obtaining unity within the

company. The flow of

information

readily

admits the participation of all members

of the organization in the program, even if on

a

part-time

basis.

Functional

managers obtain a better understanding of

how their labor fits

into the total

program

and

how their activities

interface with those of

other departments. For the

first time,

functional

managers

can accurately foresee how

their activity can lead to

corporate profits.

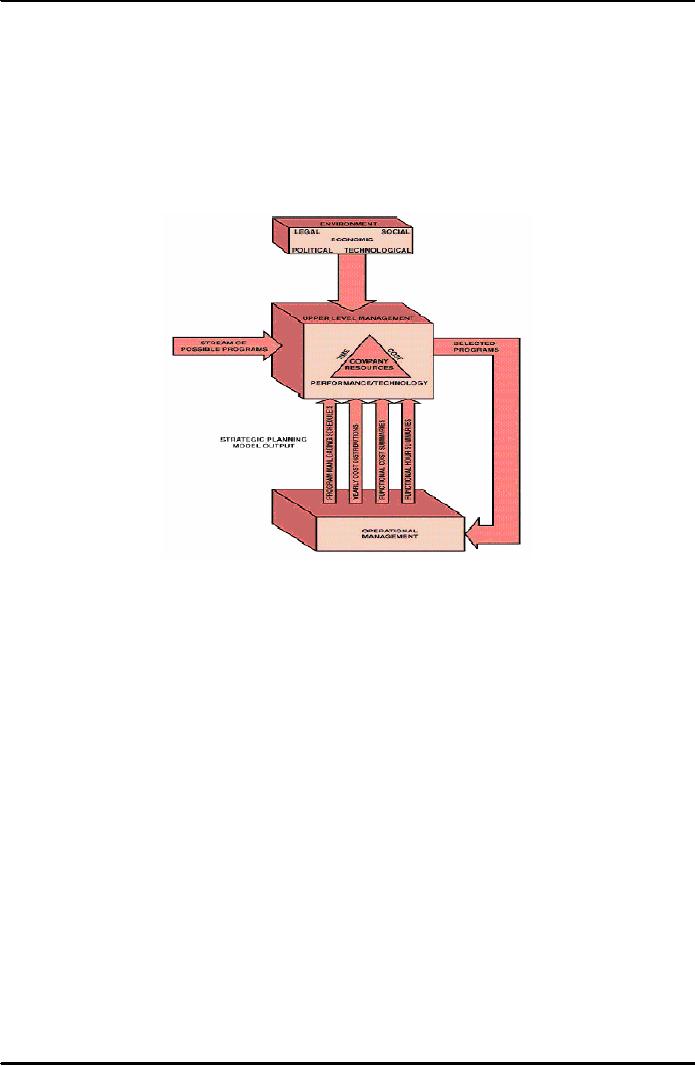

Figure

33.3: System

Approach to Resource

Control

As

shown in Figure 33.3 above the project

pricing model (sometimes

called a strategic project

planning

model) acts as a management

information system, forming the

basis for the systems

approach

to resource control. The

summary sheets from the computer

output of the strategic

pricing

model provide management

with the necessary data from

which the selection of possible

programs

can be made so that maximum

utilization of resources will

follow.

The

strategic pricing model also

provides management with an

invaluable tool for

performing

perturbation

analysis on the base case costs.

This perturbation analysis provides

management

with

sufficient opportunity for design and

evaluation of contingency plans, should a

deviation

from

the original plan be

required.

33.4

DEVELOPING

THE SUPPORTING/BACKUP

COSTS:

Remember

that not all cost

proposals require backup support,

but for those that

do, the backup

support

should be developed along

with the pricing. Extreme

caution must be exercised to

make

sure

that the itemized prices are

compatible with the supporting

data. Government

pricing

requirements

are a special case.

Most

supporting data come from

external (subcontractor or outside

vendor) quotes. Internal

data

must

be based on historical data, and

these historical data must

be updated continually as each

new

project is completed. The supporting

data should be traceable by itemized

charge numbers.

It

must be kept in mind that

customers may wish to audit

the cost proposal. In this

case, the

starting

point might be with the

supporting data. It is not uncommon on

sole-source proposals to

have

the supporting data audited

before the final cost

proposal is submitted to the

customer.

242

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

Not

all cost proposals require

supporting data; the determining factor

is usually the type of

contract.

On a fixed-price effort, the customer

may not have the right to

audit your books.

However,

for a cost-reimbursable package, your

costs are an open book, and

the customer

usually

compares your exact costs to

those of the backup support.

Commonly,

most companies usually have a choice of

more than one estimate to be

used for

backup

support. In deciding which estimate to

use, consideration must be

given to the

possibility

of follow-on work:

·

If

your actual costs grossly exceed

your backup support estimates,

you may lose

credibility

for

follow-on work.

·

If

your actual costs are less

than the backup costs, you

must use the new actual

costs on

follow-on

efforts.

We

see that the moral here is

that backup support costs

provide future credibility. If

you have

well-documented,

"livable" cost estimates,

then you may wish to

include them in the cost

proposal

even if they are not

required.

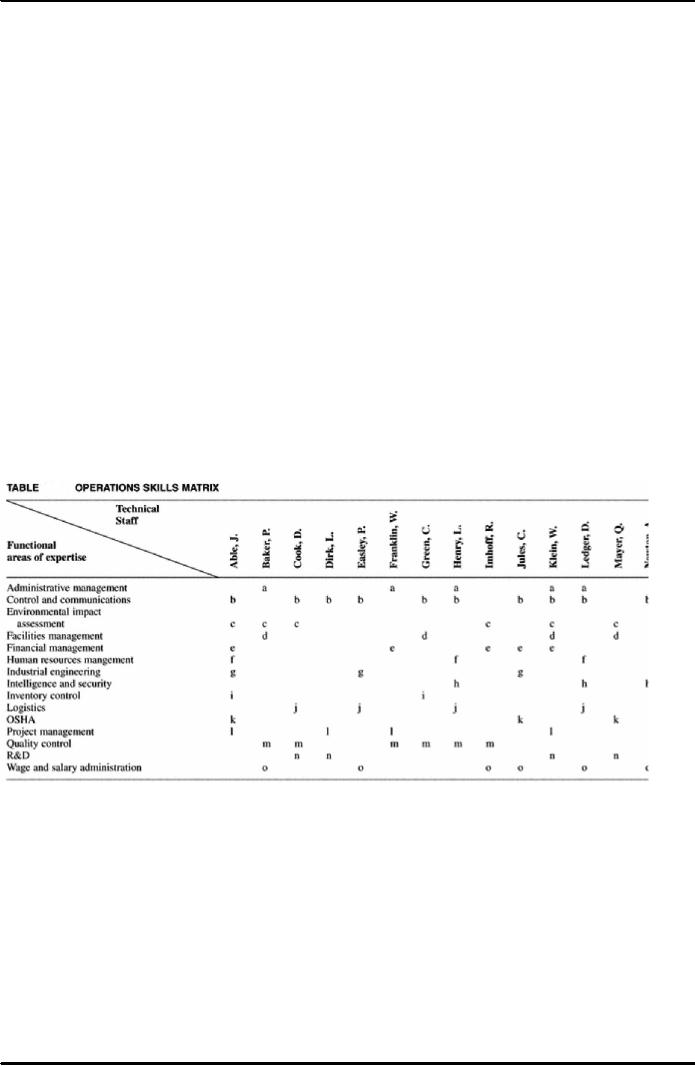

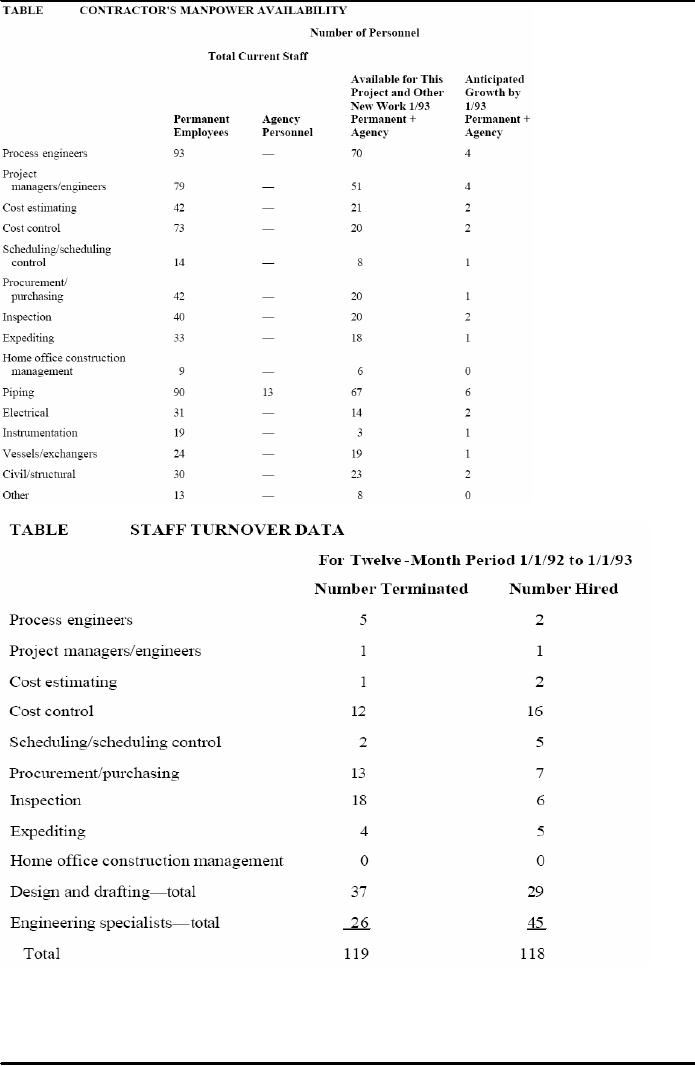

Since

both direct and indirect

costs may be negotiated separately as

part of a contract,

supporting

data such as those in the

following four Tables (33.1,

33.2, 33.3 and 33.4

respectively)

and Figure 33.4 following

them may be necessary to justify

any costs that

may

differ

from company (or customer-approved)

standards.

243

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

Tables

33.1 and 33.2

Table

33.3: Staff

Turnover Data

244

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

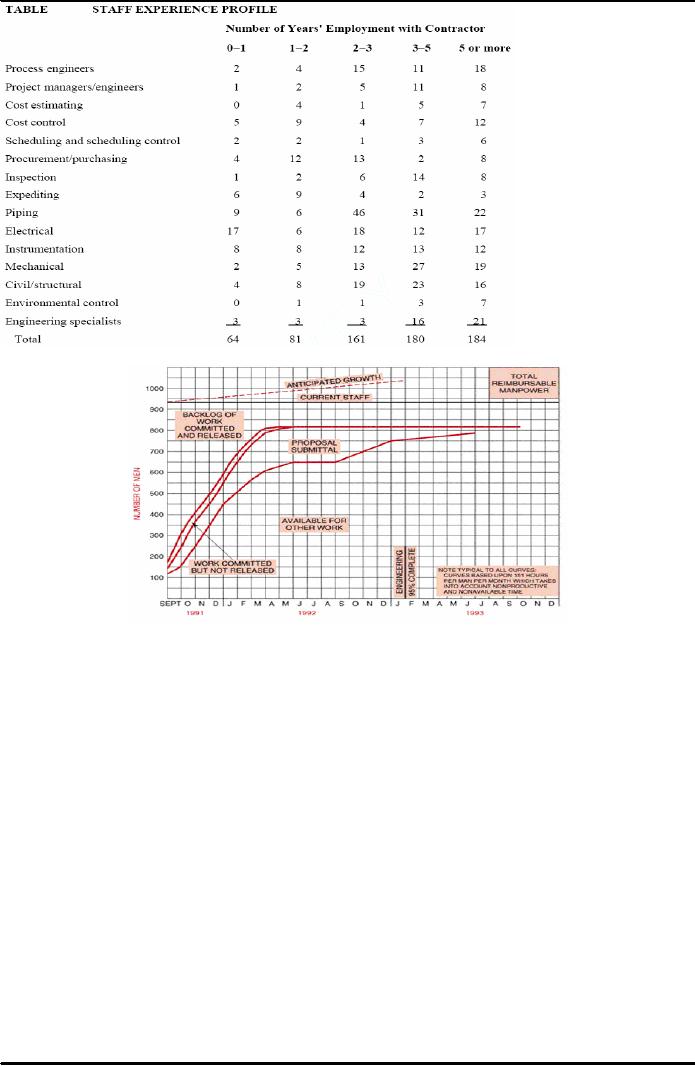

Table

33.4: Staff

Experience Profile

Figure

33.4: Total

Reimbursable Manpower

33.5

THE

LOW-BIDDER DILEMMA:

There

is little argument about the importance

of the price tag to the proposal. The

question is

what

price will win the job?

Everyone has an answer to

this question. The decision

process that

leads

to the final price of your

proposal is highly complex

with many uncertainties.

Yet

proposal

managers, driven by the desire to

win the job, may

think that a very

low-priced

proposal

will help. But, hopefully,

winning is only the beginning.

Companies have short-

and

long-range

objectives on profit, market

penetration, new product

development, and so on.

These

objectives

may be incompatible with or

irrelevant to a low-price strategy per

se; for example:

·

A

suspiciously low price,

particularly on cost-plus type proposals,

might be perceived by

the

customer as unrealistic, thus

affecting the bidder's cost credibility

or even the technical

ability

to perform.

·

The

bid price may be unnecessarily

low, relative to the competition

and customer budget,

thus

eroding profits.

·

The

price may be irrelevant to the

bid objective, such as

entering a new market.

Therefore,

the

contractor has to sell the proposal in a

credible way, e.g., using

cost sharing.

245

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

·

Low

pricing without market

information is meaningless. The

price level is always

relative

to

(1) the competitive prices, (2) the

customer budget and (3) the bidder's

cost estimate.

·

The

bid proposal and its price

may cover only part of the

total program. The ability

to win

phase

II or follow-on business depends on

phase I performance and phase II

price.

·

The

financial objectives of the customer

may be more complex than

just finding the

lowest

bidder.

They

may include cost objectives

for total system life-cycle

cost (LCC), for

design

to unit

production

cost (DTUPC), or

for specific logistic support items.

Presenting sound approaches

for

attaining these system

costperformance parameters and

targets may be just as

important as,

if

not more important than, a

low bid for the system's

development.

In

addition to this, it is refreshing to

note that in spite of customer

pressures toward low cost

and

fixed

price, the lowest bidder is

certainly not an automatic

winner. Both commercial and

governmental

customers are increasingly

concerned about cost realism

and the ability to

perform

under contract. A compliant, sound,

technical and management proposal,

based on past

experience

with realistic, well documented

cost figures, is often

chosen over the lowest

bidder,

who

may project a risky image

regarding technical performance, cost, or

schedule.

33.6

SPECIAL

PROBLEMS:

It

is essential to note that there

are always special problems that,

although often

overlooked,

have

a severe impact on the pricing

effort. As an example, pricing

must include an

understanding

of cost control-- specifically,

how costs are billed back to

the project. There

are

three

possible situations:

1.

Work

is priced out at the department average,

and all work performed is

charged to the

project

at the department average salary, regardless of

who accomplished the work. This

technique

is obviously the easiest, but

encourages project managers to

fight for the highest

salary

resources, since only

average wages are billed to

the project.

2.

Work

is priced out at the department average,

but all work performed is

billed back to the

project

at the actual salary of those

employees who perform the

work. This

method can

create

a severe headache for the

project manager if he tries to use

only the best employees

on

his project. If these employees

are earning substantially more

money than the department

average,

then a cost overrun will

occur unless the employees can

perform the work in

less

time.

Some companies are forced to

use this method by government

agencies and have

estimating

problems when the project that

has to be priced out is of a short

duration where

only

the higher-salaried employees can be

used. In such a situation it is common to

''inflate"

the

direct labor hours to compensate

for the added costs.

3.

The

work is priced out at the

actual salary of those

employees who will perform the

work,

and

the cost is billed back the

same way. This

method is the ideal situation as long as

the

people

can be identified during the

pricing effort.

In

this regard, some companies

use a combination of all three

methods. In this case, the

project

office

is priced out using the

third method (because these

people are identified

early), whereas

the

functional employees are priced

out using the first or

second method.

33.7

ESTIMATING

PITFALLS:

There

are several pitfalls that

can impede the pricing

function. Probably the most

serious pitfall,

and

the one that is usually

beyond the control of the project

manager, is the "buy-in" decision,

which

is based on the assumption that there

will be "bail-out" changes or

follow-on contracts

later.

These changes and/or

contracts may be for spares,

spare parts, maintenance,

maintenance

246

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

manuals,

equipment surveillance, optional

equipment, optional services, and

scrap factors.

Other

types of estimating pitfalls

include:

·

Misinterpretation

of the statement of work

·

Omissions

or improperly defined

scope

·

Poorly

defined or overly optimistic

schedule

·

Inaccurate

work breakdown structure

·

Applying

improper skill levels to

tasks

·

Failure

to account for risks

·

Failure

to understand or account for cost

escalation and inflation

·

Failure

to use the correct estimating

technique

·

Failure

to use forward pricing rates

for overhead, general and administrative, and

indirect

costs.

Unfortunately,

many of these pitfalls do

not become evident until

detected by the cost

control

system,

well into the

project.

247

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Broad Contents, Functions of Management

- CONCEPTS, DEFINITIONS AND NATURE OF PROJECTS:Why Projects are initiated?, Project Participants

- CONCEPTS OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT:THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT SYSTEM, Managerial Skills

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT METHODOLOGIES AND ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES:Systems, Programs, and Projects

- PROJECT LIFE CYCLES:Conceptual Phase, Implementation Phase, Engineering Project

- THE PROJECT MANAGER:Team Building Skills, Conflict Resolution Skills, Organizing

- THE PROJECT MANAGER (CONTD.):Project Champions, Project Authority Breakdown

- PROJECT CONCEPTION AND PROJECT FEASIBILITY:Feasibility Analysis

- PROJECT FEASIBILITY (CONTD.):Scope of Feasibility Analysis, Project Impacts

- PROJECT FEASIBILITY (CONTD.):Operations and Production, Sales and Marketing

- PROJECT SELECTION:Modeling, The Operating Necessity, The Competitive Necessity

- PROJECT SELECTION (CONTD.):Payback Period, Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

- PROJECT PROPOSAL:Preparation for Future Proposal, Proposal Effort

- PROJECT PROPOSAL (CONTD.):Background on the Opportunity, Costs, Resources Required

- PROJECT PLANNING:Planning of Execution, Operations, Installation and Use

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Outside Clients, Quality Control Planning

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Elements of a Project Plan, Potential Problems

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Sorting Out Project, Project Mission, Categories of Planning

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Identifying Strategic Project Variables, Competitive Resources

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Responsibilities of Key Players, Line manager will define

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):The Statement of Work (Sow)

- WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE:Characteristics of Work Package

- WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE:Why Do Plans Fail?

- SCHEDULES AND CHARTS:Master Production Scheduling, Program Plan

- TOTAL PROJECT PLANNING:Management Control, Project Fast-Tracking

- PROJECT SCOPE MANAGEMENT:Why is Scope Important?, Scope Management Plan

- PROJECT SCOPE MANAGEMENT:Project Scope Definition, Scope Change Control

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Historical Evolution of Networks, Dummy Activities

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Slack Time Calculation, Network Re-planning

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Total PERT/CPM Planning, PERT/CPM Problem Areas

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION:GLOBAL PRICING STRATEGIES, TYPES OF ESTIMATES

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.):LABOR DISTRIBUTIONS, OVERHEAD RATES

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.):MATERIALS/SUPPORT COSTS, PRICING OUT THE WORK

- QUALITY IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Value-Based Perspective, Customer-Driven Quality

- QUALITY IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT (CONTD.):Total Quality Management

- PRINCIPLES OF TOTAL QUALITY:EMPOWERMENT, COST OF QUALITY

- CUSTOMER FOCUSED PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Threshold Attributes

- QUALITY IMPROVEMENT TOOLS:Data Tables, Identify the problem, Random method

- PROJECT EFFECTIVENESS THROUGH ENHANCED PRODUCTIVITY:Messages of Productivity, Productivity Improvement

- COST MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL IN PROJECTS:Project benefits, Understanding Control

- COST MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL IN PROJECTS:Variance, Depreciation

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT THROUGH LEADERSHIP:The Tasks of Leadership, The Job of a Leader

- COMMUNICATION IN THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Cost of Correspondence, CHANNEL

- PROJECT RISK MANAGEMENT:Components of Risk, Categories of Risk, Risk Planning

- PROJECT PROCUREMENT, CONTRACT MANAGEMENT, AND ETHICS IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Procurement Cycles