|

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

37

Employee

Involvement

Quality

Circles:

Quality

circles or "employee involvement teams"

as they are often called in the

United States, were at

one

time

the most popular parallel structure

approach to EI. Originally developed in

Japan in the mid-1950s,

quality

circles consist of small

groups of employees who meet

voluntarily to identify and

solve productivity

problems.

The group method of problem

solving and the participative management

philosophy associated

with

it are natural outgrowths of Japanese

managerial practices. The

Japanese emphasize

decentralized

decision

making and use the small

group as the organization unit to promote

collective decision making

and

responsibility. Various estimates

once put the total circle

membership at as many as ten

million

Japanese

workers.

Quality

circles were introduced in the

United States in the mid-1970s.

Their growth through the

early I

980s

was nothing short of astounding,

with some four thousand

companies adopting some version of

the

circles

approach. The popularity of

quality circles can be

attributed in part to the widespread

drive to

emulate

Japanese management practices

and to achieve the quality improvements

and cost savings

associated

with those methods. What

may be overlooked, however, is the

Japanese philosophy of

decentralized,

collective decision making, which

supports and nurtures the

circles approach. Thus,

quality

circles

may be more difficult to implement in the

more autocratic, individualistic

situations that

characterize

many

American companies.

Although

quality circles are implemented in

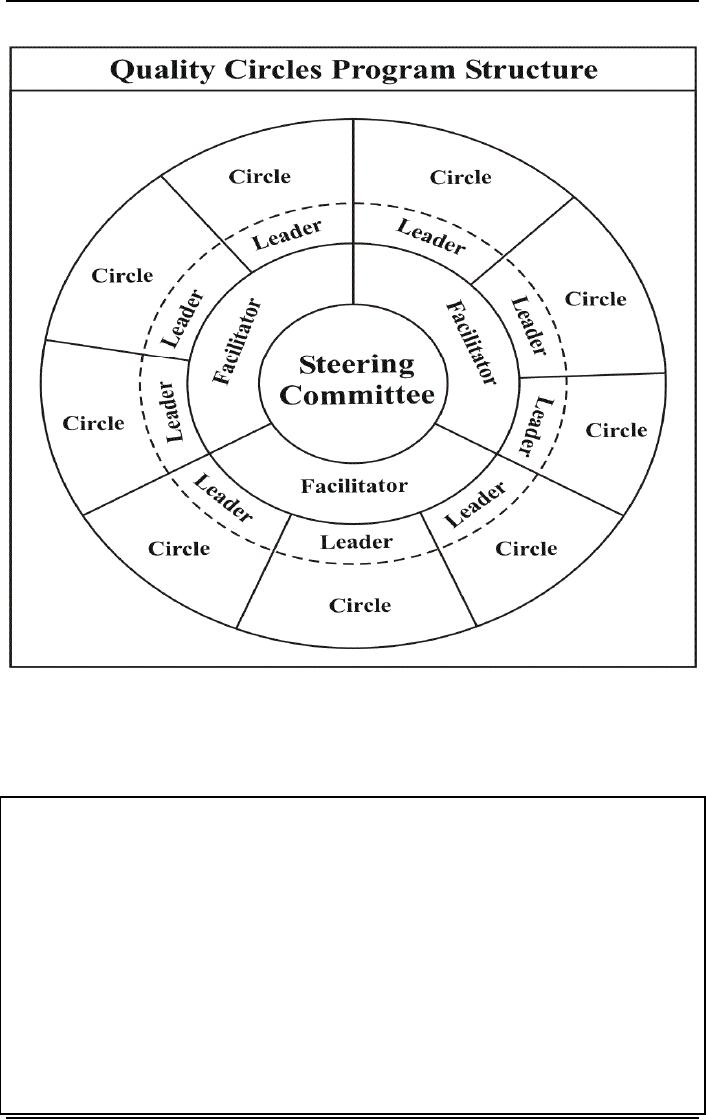

different ways, a typical program is illustrated in

Figure 49.

Circle

programs generally are implemented

with a parallel structure consisting of

several circles, each

having

three

to fifteen members Membership is

voluntary, and members of a

circle share a common job or

work

area.

Circles meet once each

week for about one hour on

company tune, several consulting

companies have

developed

training packages as part of

standardized programs for implementing

quality circles.

Members

are

trained in different prob1cm identification

and analysis techniques and

they apply their training to

identify,

analyze, and recommend solutions to

work-related problems. When possible,

they implement

solutions

that affect only their work

area and do not require higher

management approval.

Each

circle has a leader, who is

typically the supervisor of the work

area represented by circle

membership.

The

leader trains circle members

and guides the weekly

meetings, setting the agenda

and facilitating the

problem-solving

process.

Facilitators

can be a key part of a

quality circles program. They coordinate

the activities of several

circles

and

may attend the meetings, especially

during the early development stages.

Facilitators train circle

leaders

and

help them start the circles.

They also help circles

obtain needed inputs from

support groups and

keep

upper

management apprised of progress.

Because facilitators are the most

active promoters of the program,

their

role may he full

time.

A

steering committee is the central

coordinator of the quality circles

program. Generally, it is composed

of

the

facilitators and representatives of the major

functional departments in the organization.

The steering

committee

determines the policies and

procedures of the program and the issues

that tall outside of

circle

attention,

such as wages, fringe

benefits, and other topics

normally covered in union

contracts. The

committee

also coordinates training

programs and guides program

expansion. Large quality

circles

programs

might have several steering

committees operating at different

levels.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Figure

49

Application

8 presents a classic example of a

quality circles program in the warehouse

department of the

HEB

Grocery Company. The study reports mixed

results but identifies the organizational

conditions

needed

to implement effective quality

circles.

Application

8: Quality Circles at H.E.B

Grocery Company

A

quality circles program was implemented

as a pilot project at a large

warehouse of the HE-B

Grocery

Company

in Texas. Department management of this

eighty-person, two- shift

warehousing operation

volunteered

to adopt the program, which

was part of a larger corporate

strategy to increase

employee

involvement.

This choice emerged from a

survey in which employees indicated a

desire to be better

informed

about department events and to

have greater involvement in

problem solving. All but

four

workers

volunteered to be part of the pilot

circles.

The

program consisted of four circles,

each composed of ten people representing

a cross section of

workers

familiar with the warehousing

operation. The circles met

for two hours at two-week

intervals.

Because

of the large number of workers who

wished to participate in the program,

management held

periodic

rotations, replacing some circle

members with new volunteers. One

rotation occurred after

five

months:

twelve workers dropped out,

several more left the department,

and twenty-nine employees

joined

the

circles.

Each

circle had a worker-leader trained in communication

techniques, group process,

and problem-solving

skills.

The leaders also formed a

leader circle that met

regularly to exchange ideas, concerns,

and

information

and to coordinate the four circles.

Supervisors were trained and

served as resources to the

circles.

Similarly, members of the corporate human

resources department served as facilitators. They

helped

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

the

leaders train circle

members, attended the meetings,

and provided process

facilitation. The department

head

and several top managers

formed the steering committee to

guide the project. Circle suggestions

were

reported

to department management, which worked

closely with employees to implement the

suggestions.

Researchers

conducted a thorough evaluation of the

quality circles program. They

compared the warehouse

department

with a similar control group

that had not participated in the program.

Comparison measures

included

survey data at three points

in time: five months before the program,

three months after its

beginning,

and ten months after the program started,

Also included were unobtrusive

measures of

productivity,

absenteeism, and accidents

collected at four- week intervals

beginning one year before

the

program.

The researches also

conducted formal, open-ended interviews

with selected warehouse

managers

and

circle members and observed

the circles in action once a month.

All documentation that emerged

from

the

circles was examined.

In

contrast to the control group, the

warehouse department showed slightly

more positive trends

in

productivity

during the course of the circles program.

Specifically, the quantity of production

increased

slightly,

and small decreases were

shown in costs, absenteeism,

labor expense, overtime, and

accidents. The

survey

data showed that the

attitudes of warehouse employees

changed little during the program

but,

unexpectedly,

the attitudes of members of the control

group suffered in regard to feeling

informed, being

involved

in decision making, and receiving

feedback from super4sors.

The researchers attributed

this

deterioration

in morale to the disruption caused by a

rapid expansion in the workload of the

comparison

unit.

Because the expansion affected

both the warehouse and the

control group, the researchers

concluded

that

the circles program might have

buffered warehouse employees

during this disruption, accounting

for

the

stability of attitudes during the

program.

Examination

of the interview and observational data

revealed a more negative

assessment of the circles

program.

Its initial months were

marked by a flurry of activity

and improvement suggestions.

Among the

outcomes

were efforts to improve equipment

maintenance procedures, reduce

warehouse congestion,

and

prevent

damage. After several months,

attendance at the meetings began to

wane, and the circle

members

found

it increasingly difficult to identify

significant issues within their

sphere of expertise and

influence.

Supervisors

also started to admit that the

circles were draining time

and energy from the

department.

A

second flurry of activity

and enthusiasm for the program

took place soon after the

voluntary rotation of

members

into and out of the program.

With time, this energy also

subsided as members became

frustrated

with

the difficulty of systematic problem

solving, the slowness of any

implementation of ideas, and

the

failure

of the program to affect their jobs. As the

workload of the warehouse increased,

management

allowed

the circles to become inactive by

neglecting the project.

Interview

data showed that participants in the

program felt they had accomplished

something worthwhile,

had

learned a lot, and had

enjoyed the circles. Non-participants or

those who dropped out of the

circles felt

that

the program never really dealt with

significant issues, it is interesting that

those who didn't

participate

or

dropped out showed a marked

worsening of attitudes during the

program, compared with

active

participants.

This unexpected downturn was

attributed to disillusionment with the program

and to feelings

that

some participants were wasting time.

Supervisors felt that the

payback was not worth the

time spent in

the

meetings. The human

resources personnel judged the program a

successful step toward

employee

involvement

in H.E.B.

Observations

and interviews suggested several

reasons why the program gradually died.

The level of group

functioning

did not noticeably improve

during the program, and

there was

no

indication that systematic

problem-solving

techniques were followed.

implementation of several ideas

was unduly delayed in

bureaucratic

channels, resulting in member perceptions

of low management commitment to the

program-

Although

many circle members reported

satisfaction with the program,

little indication was

evident that

their

enthusiasm translated into

greater motivation on the job.

Indeed, many of the most

active participants

became

disenchanted with their jobs

and sought ways to enter the

supervisory ranks. Some

members also

felt

that they were being inadequately

compensated for generating

moneysaving ideas for the

company.

The

researchers concluded that, as a pilot

project, the quality circles program was

successful. The

company

learned

about the level of commitment and energy required to

sustain such programs and

continued to

experiment

with other approaches to

employee involvement, holding

more realistic expectations.

The

rigorous

and contradictory nature of the

assessment measures strongly suggests

that research on

quality

circles

must go beyond glowing testimonials

and superficial reports of worker

enthusiasm to include

whether

such programs effect valued

individual and organization

outcomes.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

High-Involvement

Organizations:

Over

the past several years, an

increasing number of employee involvement

projects have been aimed

at

creating

high-involvement organizations (HIOs).

These interventions create organizational

conditions that

support

high levels of employee

participation. What makes

HIOs unique is the comprehensive nature

of

their

design process. Unlike parallel

structures that do not alter the

formal organization, in HIOs almost

all

organization

features are designed

jointly by management and

workers to promote high

levels of

involvement

and performance including

structure, work design,

information and control

systems, physical

layout,

personnel policies, and

reward systems.

Features

of High Involvement Organizations:

High-involvement

organizations are designed

with features congruent with

one another. For example,

in

HIOs

employees have considerable influence

over decisions. To support

such a decentralized

philosophy,

members

receive extensive training in

problem-solving techniques, plant

operation, and organizational

policies;

in addition, both operational and

issue-oriented information is shared

widely and is obtained easily

by

employees. Finally, rewards

are tied closely to unit

performance, as well as to knowledge and

skill levels.

These

disparate aspects of the organization are

mutually reinforcing and

form a coherent pattern

that

contributes

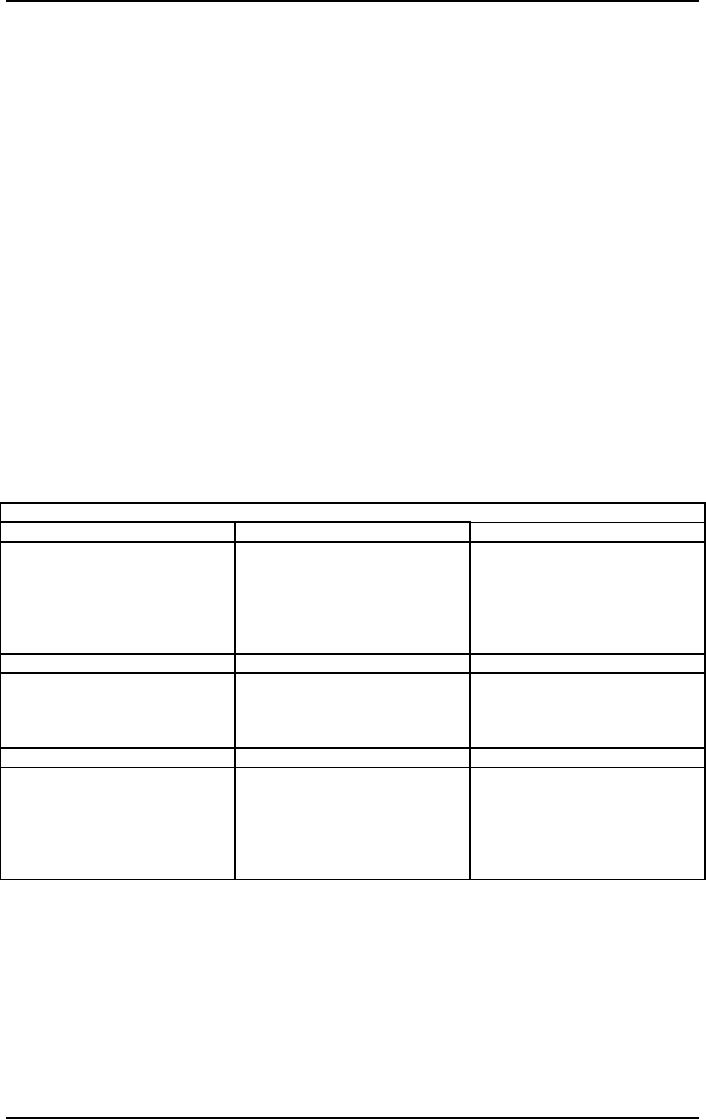

to employee involvement. Table 18

presents a list of compatible design

elements characterizing

HIOs

and most such organizations

include several if not all of the

following features:

Flat,

lean organization structures contribute

to involvement by pushing the scheduling,

planning, and

controlling

functions typically performed by

management and stall groups

toward the shop floor.

Similarly,

mini-enterprise,

team-based structures that is

oriented to a common purpose or Outcome

help focus

employee

participation on a shared objective. Participative

structures, such as work

councils and union--

management

Committees, create conditions in

which workers can influence the

direction and policies

of

the

organization.

Table

18

Design

Features for a participative

System

Organization

Structure

Job

Design

Information

System

Flat

Individually

enriched

Open

Lean

Self-managing

teams

Inclusive

Minienterprise-oriented

Tied

to jobs

Team-based

Decentralized;

team-based

Anticipatively

set goals

and

Participative

council or structure

standards

Career

System

Selection

Training

Tracks

and counseling

available

Realistic

job preview

Heavy

commitment

Open

job posting

Team-based

Peer

training

Potential

and

process-skill

Economic education

oriented

Interpersonal

skills

Reward

System

Personnel

Policies

Physical

Layout

Open

Stability

of employment

Around

organizational structure

Skill-based

Anticipatively

established through Egalitarian

Gain

sharing or ownership

representative

group

Safe

and pleasant

Flexible

benefits

All

salaried workforce

Egalitarian

perquisites

Job

designs that

provide employees with high

levels of discretion, task variety,

and meaningful feedback

can

enhance evolvement. They enable workers

to influence day-to-day workplace decisions and to

receive

intrinsic

satisfaction by performing work under

enriched conditions. Self-managed trains

encourage

employee

responsibility by providing cross-training

and job rotation, which give

people a chance to learn

about

the different functions contributing to

organizational performance.

Open

information systems that

are tied to jobs or work

teams provide the necessary

information tar

employees

to participate meaningfully in decision making.

Goals and standards of

performance that are

set

participatively

can provide employees with a

sense of commitment arid motivation for

achieving those

objectives.

Career

systems that

provide different tracks for

advancement and counseling to

help people choose

appropriate

paths can help employees

plan and prepare for

long-term development in the organization.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Open

job posting, for example,

makes employees aware of

jobs that can further

their development.

Selection

of

employees for high-involvement

organizations can be improved

through a realistic

job

preview

providing information about what it

will be like to work in such

situations. Team

member

involvement

in a selection process oriented to

potential and process skills

of recruits can facilitate a

participative

climate.

Training

employees

for the necessary knowledge and

skills to participate effectively in

decision making is a

heavy

commitment in HIOs. This effort

includes education on the economic

side of the enterprise, as

well

as

interpersonal skill development. Peer

training is emphasized as a valuable

adjunct to formal, expert

training.

Reward

systems can

contribute to employee involvement

when information about them is open and

the

rewards

are based on acquiring new

skills, as well as sharing

gains from improved

performance. Similarly,

participation

is enhanced when people can

choose among different

fringe benefits and when

reward

distinctions

among people from different

hierarchical levels are

minimized.

Personnel

policies

that are participatively set

and encourage stability of employment

provide employees

with

a strong sense of commitment to the organization.

People feel that the policies

are reasonable and

that

the

firm is committed to their long-term

development.

Physical

layouts of

organizations also can

enhance employee involvement.

Physical designs that

support

team

structures and reduce status

differences among employees

can reinforce the egalitarian climate

needed

for

employee participation. Safe

and pleasant working

conditions provide a physical

environment

conducive

to participation.

These

HIO design features are

mutually reinforcing. "They

all send a message to people in the

organization

that

says they are important,

respected, valued, capable of growing,

and trusted and that

their understanding

of

and involvement in the total organization

is desirable and expected." Moreover,

these design

components

tend to motivate and focus

organizational behavior in a strategic

direction, and thus can

lead

to

superior effectiveness and competitive

advantage, particularly in contrast to

inure traditionally

designed

organizations.

Total

Quality Management:

Total

quality management (TQM) is the

most recent and, along with

high-involvement organizations the

most

comprehensive approach to employee

involvement. Also known as

"Continuous process

improvement"

and "continuous quality," TQM

grew out of a manufacturing emphasis on

quality control

and

represents a long- term effort to

orient all of an organization's

activities around the concept of

quality.

Quality

is achieved when organizational processes reliably

produce products and services

that meet or

exceed

customer expectations.

Like

high-involvement designs, TQM increases

workers' knowledge and skills through

extensive training,

provides

relevant information to employees, pushes

decision-making power downward in the

organization

and

ties rewards to performance.

When implemented successfully. TQM also

is aligned closely with a

firm's

overall

business strategy and

attempts to change the entire organization

toward continuous quality

improvement.

Characteristics

of TQM:

TQM

is a philosophy and a set of

guiding principles for continuous

improvement based on

customer

satisfaction,

teamwork, and empowerment of individuals. TQM

applies human resources and

analytical

tools

to focus on meeting or exceeding

customer's current and future

needs. There are a series of

planned

improvements

that will ultimately influence the

quality and productivity of the

organization.

Like

high-involvement designs, TQM increases

workers' knowledge and skills through

extensive training,

provides

relevant information to employees, pushes

decision-making power downward in the

organization

and

ties rewards to

performance.

When

implemented successfully TQM also is

aligned closely with a

firm's overall business

strategy and

attempts

to change the entire organization toward continuous

quality improvement.

TQM

usually have several principles or

components in common:

TQM

is organization-wide. The

production line is natural and

obvious place to improve

quality, but

TQM

also takes place in the

accounting, human resource

management, house-keeping, marketing,

sales,

and

in other service and staff

areas of an organization.

The

CEO and other top managers

support it. Everyone,

from top managers to hourly

employees,

operates

under TQM. There is a reward system in

place that ensures continual

support.

Organization

wide TQM generally takes three or

more years. So allocation of significant

resources for

training

is a crucial aspect. Motorola

company has developed a University, a

training organization, that

teaches

in twenty-seven languages. It allocates

at least 1.5 percent of its

budget to education, and

every

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

employee

must take a minimum of forty

hours of training a year. This

effort supports the Company's

goals

of

"six sigma" quality -a

statistical measure of product

quality that implies 99.9997

% perfection. Having a

work-force

that is able to read, write,

solve problems, and do math

at the seventh-grade level or

above.

TQM

is an ingrained value in the corporate

culture. Continuous

improvement penetrates the culture

and

values of the organization. Quality is

seen as "how we do things around

here."

Partnership

with customers and

suppliers. The

organization encourages partnerships with

suppliers and

customers.

The product or service must

meet or exceed the customer's

expectations. Results not

slogans

represent quality.

For

example, a leading garments

company found that the

retailers were out of stock

on 30 percent of their

items

100 percent of the time. In response, the

company revamped its systems

to fill orders within

twenty-

four

hours 95 percent of the time.

Everyone

in an organization has a customer. The

customer may be internal or external.

The next

person

on the production line, another

department, and someone

outside the organization who

purchases

the

product are all seen as

customers.

Reduced

cycle time.

Cycle times for products,

services, as well as support functions,

focus on doing the

job

faster.

Techniques

range in scope. The

techniques used in TQM include

statistical quality control,

job design,

empowerment,

and self-managed work

teams.

Do

it right the first

time.

Quality is not obtained by

rejecting a product at the end of a

production line;

rather

it is built in at every stage of the

production process.

Organization

values and respects everyone.

This

includes customers, suppliers,

employees, owners,

community,

and the environment. These

parties are often called

stakeholders.

No

single formula works fit

everyone. Every

organization is unique, and off-the-shelf

programs tend not

to

work. "What was successful

at one company may not

work in another."

Application

8: Total Quality Management at

L.L. Bean

Customers

of L.LBean know that they are the

boss. They can order

hunting equipment twenty-four hours

a

day.

They can request fishing

poles to arrive, via Federal Express,

within two days--at no extra

charge. And

they

can return broken car

racks after years of use. To

say that the Maine-based mail-

order company has a

reputation

for superior customer service is an

understatement. The company's

history is replete with

stories

of

employees who went out of

their way for a customer.

L.L.Bean has a reputation that

dates back to 1912,

when

founder Leon Leonwood Bean

made good on nearly an entire shipment of

hunting shoes that

came

back

to him with defective stitching.

That

reputation prompted Leon

Gorman, the grandson of Bean

and current chairman of L.L.Bean,

to

apply

for the Malcolm Baldridge National

Quality Award in the service

category in 1988, the first

year the

award

came out. Despite its

reputation, L.L.Bean won no award

that year, although it was

one of two

companies

that qualified for a site

Visit. No award was given

that year in the service

category.

At

the time, German noted that L.L.Bean

"will be under a great deal of

pressure to renew and

enhance our

quality

improvement efforts to make

sure we live up to our

reputation." Consequently, the company

used

feedback

from the Baldridge committee as

diagnostic information to carry

out Gorman's desire to

renew

and

enhance the company's quality

improvement efforts. This

resulted in a change program that

focused

first

on employee involvement and

then on process improvement.

The

Baldridge feedback prompted Bean to

take a hard look at its

quality culture, Although members of

the

award

committee had been impressed

with Bean's customer service

and cited it as "world class,"

they

thought

that the firm was not

achieving customer satisfaction in a

productive way. Bean had

been satisfying

customers

through a guarantee-based approach to

quality; in fact, they pioneered the "no-questions

asked"

guarantee.

The Baldridge committee members

thought that Bean should not

rely on a guarantee but should

ensure

that things happen right the

first time. A favorite company

story illustrates the situation: A

customer

service

representative in Freeport, Maine, once

strapped a canoe on his car

and drove it to a customer

in

New

York, who was leaving the

next morning for a hunting

trip. Although this certainly

demonstrated

exemplary

customer service, the award

committee noted that it also

served as a sign that

something was

wrong.

The canoe had been ordered

in plenty of time to be shipped; had the

order been processed

properly

in

the first place, there would

have been no need for

heroics.

The

diagnostic information also

revealed that Bean needed to

have more employee

involvement. This came

as

a surprise to management because the

firm prided itself on a participative

culture. L.L.Bean had been

one

of the first organizations in the United

States to implement quality circles ten

years earlier. Certainly,

managers

argued, the employee who delivered the

canoe was involved. What

members of L.L.Bean had

trouble

understanding was the practice of

letting people take responsibility for

their work and the

work

quality.

In fact, decision making at L.L.Bean had

usually taken place at a

high level.

Based

on the diagnostic feedback, the organization

first developed a definition for what

was referred to as

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

"total

quality" (TQ). It proposed that

"total quality involves

managing an enterprise to maximize

customer

satisfaction

in the most efficient and effective

way possible by totally

involving people in improving the

way

work

is done." In short, the company defined

TQ as the way to involve its people

and to improve

customer-service

processes.

Next,

L.L.Bean focused on training. It spent

approximately ten months familiarizing its

three thousand

employees

with TQ methods and what

quality means to the firm. First,

all salaried employees in

the

organization

received three days of TQ

training, and then all

hourly workers received one

day. Senior

executives

were trained first so that

each level within the company

was capable of supporting

total quality

as

the next level down learned

about it.

During

this training period, Bean's

human resources department explored ways

to change the infrastructure

of

the company to support greater

employee involvement in decisions

that affect quality. It concluded

that

because

L.L.Bean is a service organization, decisions

that influence quality occur

every time a customer

calls

one

of its phone centers and

talks to a customer service

representative. Thus, frontline,

customer-contact

employees

needed to be knowledgeable and

empowered. This would require a

new managerial role aimed

at

involving

employees and helping them develop the

necessary expertise.

Soon

after the training, Bean enlisted

seventy members to devise

ways to put the knowledge into action

and

to

challenge the status quo. They formed

seven cross-functional teams composed of

both managers and

workers.

One team defined the manager's

role in a quality-oriented organization as

that of coach and

developer,

and created a program to help

managers acquire the knowledge and

skills to fill this new

role.

Another

team constructed a feedback instrument as

part of a management development process.

The tool

eventually

became part of a performance

management process that

linked managers' compensation

to

improvements

in such behaviors as being "aspiring

and focused, ethical and

compassionate, customer

focused

and aligned, effective and

efficient, challenging and empowering,

open and innovating,

and

rewarding

and developing."

Employee

involvement also paid big dividends in

L.L.Bean's process improvement

efforts. At the

manufacturing

division, a manager of footwear

production shut down an entire

work line, despite

tremendous

productivity pressures, and

spent the morning teaching

workers how a shoe is costed

out. He

explained

each of the operations involved in making a

shoe and described the cost

of each task and of

the

materials

involved. He then took

employees back to the production

line and asked them to

discover ways

that

they could save money based

on what they had learned in the morning.

Employees found enough

savings

that day to pay for

all the training conducted in the

department for the entire year. In another

case,

stockers

who replenish shelves in

Bean's retail store swapped

jobs temporarily with

pickers who gather

store

orders from inventory in the

distribution center. They applied TQ

methods, such as

work-flow

mapping,

to understand the work relationship

between the store and the

distribution center. In the

old

process,

retail workers placed orders

with the distribution center

for items running low in the

store. Pickers

at

the distribution center gathered

those items on rolling

carts, packed them in boxes,

and loaded them

onto

trucks. `When the items arrived at the

store, stockers unloaded and unwrapped

them and put them on

rolling

carts for transportation to the

shelves. When the employees

saw both sides of the work

process,

they

realized that there was no

reason for packaging the

items. Now, the pickers

simply roll the carts

holding

items directly on to trucks so that

stockers can roll them right

off.

To

support these process improvements,

L.L.Bean's staff groups also

changed. The human

resources

department,

for example, expanded its

role to help employees

understand and manage the TQ

process. The

department

reengineered itself from a

functional structure to a

customer-oriented organization.

Now,

service

teams made up of human

resources specialists support

each of LL.Bean's major divisions

with

process

improvement techniques, health and

safety advice, employee relations help,

and training.

Most

gratifying to L.L.Bean is that through

all the changes, customer

satisfaction remained high

and job

satisfaction

among the workforce increased

more than 12 percent.

Although L.L.Bean is only halfway

through

its TQ intervention, it has

experienced increased profitability,

return on sales, and return

on equity.

TQM

and OD have Similar

Values:

TQM

& OD share certain values.

Both are system-wide, depend

on planned change, believe in

empowerment

and involvement, are

self-renewing and continuous, base

decision-making on data-based

activities,

and view people as having inherent

desire to contribute in meaningful

ways.

There

are differences, however, between OD

and TQM. Some OD practitioners

argue that their

core

values

differ, and they caution against OD

practitioners assuming the role of

"quality management

expert."

The

OD practitioner has to enter the

organization as a neutral party and resists

advocating any particular

method

of change. OD practitioners view organization

problems as having a variety of causes

with no

predefined

solutions. TQM consultant, on the other

hand, views organization problems as

having TQM

solutions.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

TQM

can be applied as one change

methodology along with an accompanying

array of other

interventions.

TQM

is more likely to be successful when

combined with employee involvement.

The two are

complementary,

and the impact of either is diminished by the

absence of the other.

Table of Contents:

- The Challenge for Organizations:The Growth and Relevance of OD

- OD: A Unique Change Strategy:OD consultants utilize a behavioral science base

- What an “ideal” effective, healthy organization would look like?:

- The Evolution of OD:Laboratory Training, Likert Scale, Scoring and analysis,

- The Evolution of OD:Participative Management, Quality of Work Life, Strategic Change

- The Organization Culture:Adjustment to Cultural Norms, Psychological Contracts

- The Nature of Planned Change:Lewin’s Change Model, Case Example: British Airways

- Action Research Model:Termination of the OD Effort, Phases not Steps

- General Model of Planned Change:Entering and Contracting, Magnitude of Change

- The Organization Development Practitioner:External and Internal Practitioners

- Creating a Climate for Change:The Stabilizer Style, The Analyzer Style

- OD Practitioner Skills and Activities:Consultant’s Abilities, Marginality

- Professional Values:Professional Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, Technical Ineptness

- Entering and Contracting:Clarifying the Organizational Issue, Selecting an OD Practitioner

- Diagnosing Organizations:The Process, The Performance Gap, The Interview Data

- Organization as Open Systems:Equifinality, Diagnosing Organizational Systems

- Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Methods for Collecting Data, Observations

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Sampling, The Analysis of Data

- Designing Interventions:Readiness for Change, Techno-structural Interventions

- Leading and Managing Change:Motivating Change, The Life Cycle of Resistance to Change

- Leading and managing change:Describing the Core Ideology, Commitment Planning

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Measurement

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Research Design

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Group Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Leadership and Authority, Group Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Third-Party Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Building, Team Building Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Management Styles

- Organization Process Approaches:Application Stages, Microcosm Groups

- Restructuring Organizations:Structural Design, Process-Based Structures

- Restructuring Organizations:Downsizing, Application Stages, Reengineering

- Employee Involvement:Parallel Structures, Multiple-level committees

- Employee Involvement:Quality Circles, Total Quality Management

- Work Design:The Engineering Approach, Individual Differences, Vertical Loading

- Performance Management:Goal Setting, Management by Objectives, Criticism of MBO

- Developing and Assisting Members:Career Stages, Career Planning, Job Pathing

- Developing and Assisting Members:Culture and Values, Employee Assistance Programs

- Organization and Environment Relationships:Environmental Dimensions, Administrative Responses

- Organization Transformation:Sharing the Vision, Three kinds of Interventions

- The Behavioral Approach:The Deep Assumptions Approach

- Seven Practices of Successful Organizations:Training, Sharing Information