|

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

19

Diagnosing

Groups and Jobs

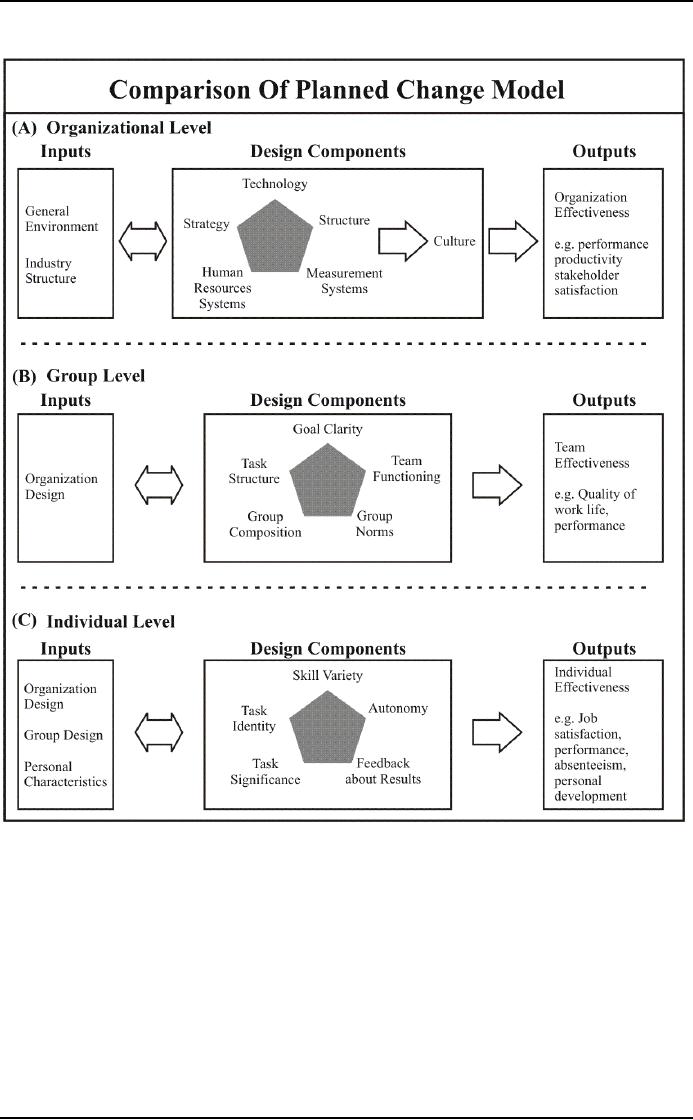

Figure

25: Comprehensive Model for

Diagnosing Organizational

Systems

Individual-Level

Diagnosis:

The

lowest level of organizational diagnosis is the

individual job or position. An

organization consists of

numerous

groups; a group, in turn, is composed of

several individual jobs. This

section discusses the

inputs,

design components, and relational

fits for diagnosing jobs.

The model shown in Figure 25(C)

is

similar

to other popular job

diagnostic frameworks, such as

Hackrnan and Oldhamn's job

diagnostic survey

and

Herzberg's job enrichment model.

Inputs:

Three

major inputs affect job design:

organization design, group design,

and the personal characteristics

of

job

holders.

Organization

design is concerned with the

larger organization within which the

individual job is the

smallest

unit. Organization design is a key

part of the larger context surrounding

jobs. Technology,

structure,

measurement systems, human

resources systems, and culture

can have a powerful impact

on the

way

jobs are designed and on

people's experiences in jobs.

For example, company reward

systems can

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

orient

employees to particular job behaviors

and influence whether people see job

performance as fairly

rewarded.

In general, technology characterized by relatively

uncertain tasks and low

interdependency is

likely

to support job designs allowing

employees flexibility and discretion in

performing tasks.

Conversely,

low-uncertainty

work systems are likely to

promote standardized job

designs requiring routinized

task

behaviors.

Group

design concerns the larger

group or department containing the

individual job. Like

organization

design,

group design is an essential

part of the job context. Group

task structure, goal

clarity, composition,

performance

norms, and group functioning

serve as inputs to job design. They

typically have a more

immediate

impact on jobs than do the larger,

organization-design components. For

example, group task

structure

can determine how individual

jobs are grouped together -- as in groups

requiring coordination

among

jobs or in ones comprising collections of independent

jobs. Group composition can

influence the

kinds

of people who are available to

fill jobs. Group performance

norms can affect the kinds of job

designs

that

are considered acceptable,

including the level of job holders'

performances. Goal clarity helps

members

to

prioritize work, and group

functioning can affect how

powerfully the group influences

job behaviors.

When

members maintain close relationships and

the group is cohesive, group

norms are more likely to

be

enforced

and followed.

Personal

characteristics of individuals occupying

jobs include their age, education,

experience, and skills

and

abilities.

All of these can affect job

performance as well as how people

react to job designs.

Individual

needs

and expectations can also

affect employee job responses.

For example, individual

differences in

growth

need -- the need for self-direction,

learning, and personal accomplishment --

can determine how

much

people are motivated and

satisfied by jobs with high

levels of skill variety,

autonomy, and

feedback

about

results. Similarly, work motivation

can be influenced by people's

expectations that they can

perform

a

job well and that

good job performance will

result in valued

outcomes.

Design

Components:

Figure

25(C) shows that individual

jobs have five key

dimensions: skill variety,

task identity, task

significance,

autonomy, and feedback about

results.

Skill

variety identifies the degree to which a

job requires a range of

activities and abilities to perform

the

work.

Assembly-line jobs, for example,

generally have limited skill

variety because employees perform

a

small

number of repetitive activities. Most

professional jobs, on the other

hand, include a great deal of

skill

variety

because people engage in diverse

activities and employ several different

skills in performing

their

work.

Task

identity measures the degree to

which a job requires the

completion of a relatively whole,

identifiable

piece

of work. Skilled craftspeople, such as

tool-and-die makers and

carpenters, generally have

jobs with

high

levels of task identity. They

are able to see a job

through from beginning to end.

Assembly-line jobs

involve

only

a

limited

piece

of

work

and

score

low

on

task

identity.

Task

significance identifies the degree to

which a job has a significant

impact on other people's

lives.

Custodial

jobs in a hospital are likely to

have more task significance

than similar jobs in a toy

factory

because

hospital custodians are likely to

see their jobs as affecting

someone else's health and

welfare.

Autonomy

indicates the degree to which a

job provides freedom and discretion in

scheduling the work

and

determining

work methods. Assembly-line jobs

generally have little autonomy: the

work pace is

scheduled,

and

people perform programmed tasks.

College teaching positions have

more autonomy: professors

usually

can

determine how a course is taught,

even though they may have

limited say over class

scheduling.

Feedback

about results involves the degree to

which a job provides employees

with direct and clear

information

about the effectiveness of task

performance. Assembly-line jobs often

provide high levels

of

feedback

about results, whereas college

professors must often contend

with indirect and

ambiguous

feedback

about how they are performing in the

classroom.

Those

five job dimensions can be

combined into an overall measure of

job enrichment. Enriched jobs

have

high

levels of skill variety,

task identity, task

significance, autonomy, and

feedback about results.

They

provide

opportunities for self

direction, learning, and personal

accomplishment at work. Many people

find

enriched

jobs internally motivating

and satisfying.

Fits:

The

diagnostic model in Figure 25(C) suggests

that job design must

fit job inputs to produce effective

job

outputs,

such as high quality and

quantity of individual performance,

low absenteeism, and high

job

satisfaction.

Research reveals the following

fits between job inputs and

job design:

1.

Job

design should be congruent with the

larger organization and group

designs within which

the

job

is embedded. Both the organization and

the group serve as a powerful

context for individual jobs

or

positions.

They tend to support and

reinforce particular job

designs.

Highly differentiated

and

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

integrated

organizations and groups

that permit members to

self-regulate their behavior

fit enriched jobs.

These

larger organizations and

groups promote autonomy,

flexibility, and innovation at the

individual

job

level. Conversely, bureaucratic

organizations and groups

relying on external controls are congruent

with

job

designs scoring low on the

five key dimensions. Both

organizations and groups reinforce

standardized,

routine

jobs. As suggested earlier, congruence

across different levels of organization

design promotes

integration

of the organization, group, and job

levels. Whenever the levels do

not fit each other,

conflict is

likely

to emerge.

2.

Job

design should fit the personal

characteristics of the jobholders if they are to

perform

effectively

and derive satisfaction from

work. Generally, enriched

jobs fit people with

strong

growth needs. These people derive

satisfaction and accomplishment

from

performing

jobs

involving skill variety,

autonomy, and feedback about

results. Enriched jobs also

fit

people

possessing moderate to high

levels of task-relevant skills,

abilities, and knowledge.

Enriched

jobs generally require complex

information processing and

decision making;

people

must have comparable skills

and abilities to perform effectively.

Jobs scoring low on

the

five

job dimensions generally fit

people with rudimentary skills and

abilities and with low

growth

needs.

Simpler, more routinized jobs requiring

limited skills and

experience fit better with

people

who

place a low value on

opportunities for self-

direction and learning. In

addition, because

people

can grow through education,

training, and experience,

job design must he monitored

and

adjusted

from time to time.

Table of Contents:

- The Challenge for Organizations:The Growth and Relevance of OD

- OD: A Unique Change Strategy:OD consultants utilize a behavioral science base

- What an “ideal” effective, healthy organization would look like?:

- The Evolution of OD:Laboratory Training, Likert Scale, Scoring and analysis,

- The Evolution of OD:Participative Management, Quality of Work Life, Strategic Change

- The Organization Culture:Adjustment to Cultural Norms, Psychological Contracts

- The Nature of Planned Change:Lewin’s Change Model, Case Example: British Airways

- Action Research Model:Termination of the OD Effort, Phases not Steps

- General Model of Planned Change:Entering and Contracting, Magnitude of Change

- The Organization Development Practitioner:External and Internal Practitioners

- Creating a Climate for Change:The Stabilizer Style, The Analyzer Style

- OD Practitioner Skills and Activities:Consultant’s Abilities, Marginality

- Professional Values:Professional Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, Technical Ineptness

- Entering and Contracting:Clarifying the Organizational Issue, Selecting an OD Practitioner

- Diagnosing Organizations:The Process, The Performance Gap, The Interview Data

- Organization as Open Systems:Equifinality, Diagnosing Organizational Systems

- Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Methods for Collecting Data, Observations

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Sampling, The Analysis of Data

- Designing Interventions:Readiness for Change, Techno-structural Interventions

- Leading and Managing Change:Motivating Change, The Life Cycle of Resistance to Change

- Leading and managing change:Describing the Core Ideology, Commitment Planning

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Measurement

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Research Design

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Group Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Leadership and Authority, Group Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Third-Party Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Building, Team Building Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Management Styles

- Organization Process Approaches:Application Stages, Microcosm Groups

- Restructuring Organizations:Structural Design, Process-Based Structures

- Restructuring Organizations:Downsizing, Application Stages, Reengineering

- Employee Involvement:Parallel Structures, Multiple-level committees

- Employee Involvement:Quality Circles, Total Quality Management

- Work Design:The Engineering Approach, Individual Differences, Vertical Loading

- Performance Management:Goal Setting, Management by Objectives, Criticism of MBO

- Developing and Assisting Members:Career Stages, Career Planning, Job Pathing

- Developing and Assisting Members:Culture and Values, Employee Assistance Programs

- Organization and Environment Relationships:Environmental Dimensions, Administrative Responses

- Organization Transformation:Sharing the Vision, Three kinds of Interventions

- The Behavioral Approach:The Deep Assumptions Approach

- Seven Practices of Successful Organizations:Training, Sharing Information