|

COUNSELING PROCESS:Transference & Counter-transference |

| << COUNSELING PROCESS:The Initial Session, Counselor-initiated, Advice Giving |

| THEORY IN THE PRACTICE OF COUNSELING:Timing of Termination >> |

Theory

and Practice of Counseling -

PSY632

VU

Lesson

21

COUNSELING

PROCESS

Initial

Resistances

�

Resistances

may be broadly defined as

anything that gets in the

way of counseling.

�

Resistances

can be present at any stage

of counseling.

�

Most

clients are ambivalent when they

come for counseling. At the

same time as wanting change, they

may

have anxieties both about

changing and about the

counseling process, for

instance, talking

about

themselves.

Some clients come reluctantly:

for example, 'problem'

children sent to school

counselors

for

disrupting class.

�

Sullivan

(1954) observed cultural resistance in

non-medical counseling. Sullivan (1954)

observed that

there

were cultural handicaps to the work of

the psychiatrist. These 'anti-psychiatric' or

`anti-counselor'

elements

in the culture can also lead to

resistances in non-medical counseling.

Such culturally

handicapping

norms include: people ought not to

need help.

Other

cultural thinking errors contributing to

resistances are that people

who need helping are

'sick and

that

you should be able to solve

all problems by 'common sense'. A

study about Pakistani

people's

perceptions

about those seeking medical

or psychological help showed

that people seeking help

for

depression

were perceived as less

intelligent, sociable, kind,

etc (Suhail & Anjum,

2004).

�

Sometime

resistance could be as a consequence of

poor counseling skills or

models. Counselors

may

wrongly

attribute the sources of clients'

resistances by being too quick to

blame them for lack

of

cooperation

and progress which may

actually be the consequence of poor

counseling skills,

for

example,

not listening properly. Furthermore, some

counseling models, especially if

incompetently

applied,

may engender resistances:

for instance, the lack of

structure of the person-centered

counseling

or

the didactic nature of the rational

emotive behavior counseling. Clients

may resist counselors

whose

behavior

is too discrepant from their

expectations and perceived

requirements

�

Counselors

also bring resistances to

their work, for example,

fatigue, and burnout. One

counselor

mentioned

that once he counseled a 59-year-old

female client whose manipulative manner

triggered

anxieties

in him because she reminded

him of how his mother

sometimes controlled how he should

feel

and

think when a child.

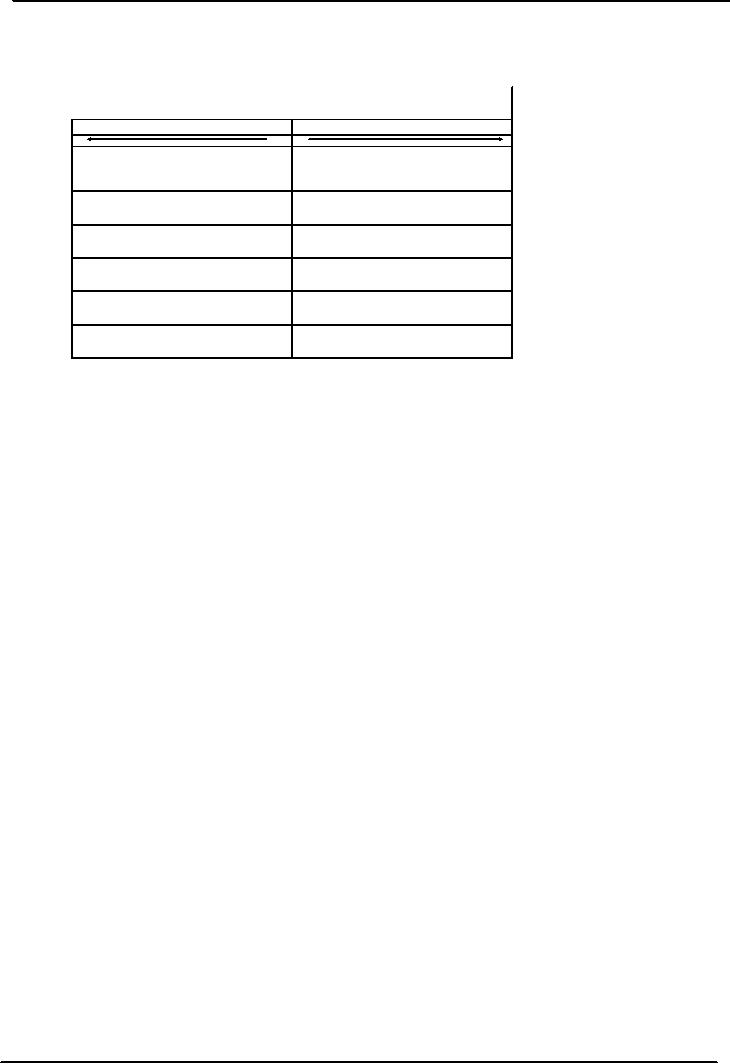

The

following tables illustrate how

different restraining and driving

forces could interplay in

resistance.

90

Theory

and Practice of Counseling -

PSY632

VU

Ta

ble 1: "Driving " a nd "Restraini ng"

forces

Restraining

Forces

Driving

Forces

5

4

3

2

1

1

2

3

4

5

A

B

C

D

E

How

to deal with Initial

Resistances?

�

Use

non-judgmental listening to convey

understanding: By

using good active listening

skills, you do much

to

build

the trust needed to lower

resistances.

�

Communicate

acceptance of

client's unwillingness to change:

Rather than justify yourself or

allow yourself to

be

sucked into a competitive

contest, one approach to

handling such aggression is to

reflect.

�

Join

with clients.

Example

of joining with

clients:

Client:

I

think coming here is a waste of time. My

parents keep picking on me

and they are the ones

who

need

help.

Family

Counselor You

feel angry about coming here because

your parents are the people

with problems.

Client:

Yes

(and then proceeds to share

his/her side of the

story).

Just

showing clients that you

understand their internal viewpoints,

especially if done consistently,

may

diminish

resistances. For instance,

counselors can initially listen

and offer support to

children expressing

resentment

about parents. In the above

instance you can focus on

parental deficiencies prior

to, possibly,

focusing

the client back on himself or herself.

You use your client's

need to talk about parental

injustices to

build

the counseling relationship.

The

above are just some

ways of working with

resistances and reluctance.

Counselors need to be

sensitive

to

the pace at which different

clients work. Clients who

feel pressured by counselors may

become even

more

resistant. Furthermore, if attacked prematurely

and clumsily, clients may reinforce

their defenses.

When

dealing with client

resistances, counselors require sensitivity,

realism, flexibility and

tact.

�

Discuss

reluctance and

fears

In

the following example, a parole officer

responds to a juvenile delinquent's

seeming reluctance to

disclose

anything

significant.

Counselor:

I

detect an unwillingness to open up to me because

I'm your parole counselors. If

I'm right, I'm

wondering

what specifically worries you

about that.

91

Theory

and Practice of Counseling -

PSY632

VU

�

Invite

cooperation

Initial

statements by counselors aim to

create the idea of a partnership, a

shared endeavor in which

clients

and

counselors can work together to attain

goals.

�

Enlist

client self-interest

It

helps clients to identify

reasons for participating in

counseling. `What are your

goals in the situation?' and

`Wouldn't

you, like to be more in control of

your life?'

�

Reward

silent

clients for talking.

Transference

& Counter-transference

These

are concepts as old as Freud.

Transference and counter-transference

are issues that affect all

forms

of

counseling, guidance, and

psychotherapy.

Transference:

�

Transference

can be direct or indirect and it is the

client's projection of past or

present feelings,

attitudes,

or desires or relationships onto the

counselor. It originally emphasized the

transference of

earlier

emotions, but today it is not

restricted to psychoanalytic therapy and

may be based on current

experiences.

�

According

to Gelso and Carter (1985),

all counselors have a

transference pull, which is an

image

generated

through the use of personality and a

particular theoretical approach. The way

counselor

speaks,

looks, gestures, or sits may trigger a

client's reaction.

�

Cavanagh

(1982) describes that

transference can be either direct or

indirect. Direct transference is

well

represented

by the example of the client who

thinks of the counselor as his/her

mother. Indirect

transference

is harder to recognize. It is usually

revealed in client's reactions

and behavior.

�

Transference

can be both negative and

positive. Cavanagh (1982) considers

both as forms of resistance.

�

Corey

at al. (1993) sees a therapeutic

value in working through

transference. Mild or indirect

positive

transference

is less harmful. Corey

believes that the relationship improves

once the client

resolves

distorted

perceptions about the counselor. It is

reflected in client's increased trust

and confidence in the

counselor.

Counter

Transference

Cavanagh

maintains that to resolve

transference the counselor may

work directly and interpersonally

rather

than

analytically, called counter transference. It is the

counselor's projected emotional reaction to

or

behavior

towards the client. It can take on

many forms, from a desire to

please the client, to wanting to

develop

a social or sexual relationship with the

client, to identify with the problems of

the client so much

that

one loses objectivity,

giving advice compulsively, etc.

(Corey et al., 1993) . When

this happens,

supervision

or counseling for the counselor is

called for.

�

Three

approaches to counter

transference:

Negative

Positive

Both

positive and negative

Counter

transference refers to negative

and positive feelings

towards clients based on

unresolved areas in

counselors'

lives. Intentionally or unintentionally

some counselors use both

involving and information

self-

disclosures

to manipulate clients to meet needs

for approval, intimacy and

sex.

92

Theory

and Practice of Counseling -

PSY632

VU

�

Watkins

(1985) identifies four forms of counter

transference:

o

Overprotective

o

Benign

o

Rejecting

o

Hostile

The

first two are examples of

identification, while the rest

show misidentification. This highlights

the

importance

both of awareness of your

motivation (for example, a

counselor was aware that a

59-year-old

female

client's manipulative manner triggered

anxieties in him because she

reminded him of how his

mother

sometimes

controlled how he should feel and

think when a child) and also

of behaving ethically.

Working

through counter transference

�

Some

pointers in effectively dealing with

transference or client's reactions to

you are:

o

Be

willing to examine your own

reactions

o

Monitor

your own counter

transference

o

Seek

supervision or consultation with

difficult cases

o

Avoid

blaming or judging the client

o

Avoid

labeling clients

o

Demonstrate

understanding and

respect

The

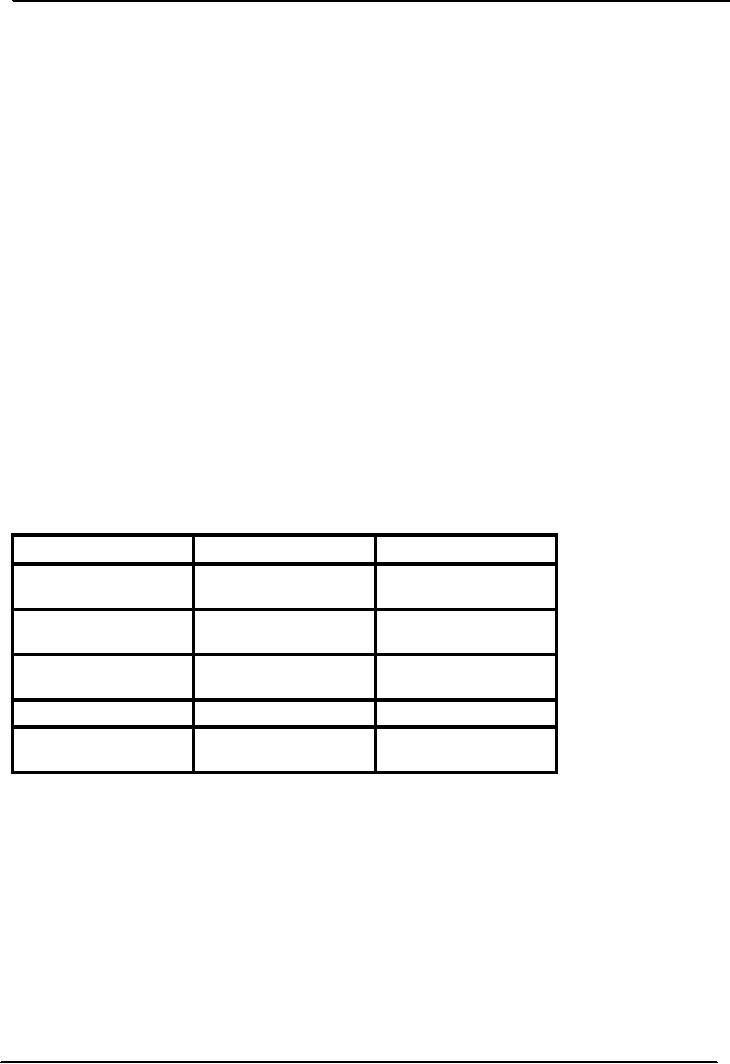

following table describes attitudes of

both client and counselor in

different transference

patterns.

Table

2: Patterns of Transference (Watkins,

1983)

Transferring

Pattern

Client

Attitude

Counselor

Attitude

Ideal

Idealizes,

imitates, hungry Feels pride;

angry

for

presence

Seer

Views

counselor as expert, Feeling of al-

knowing; self-

asks

advices

doubts

Nurturer

Profuse

emotions, sense of Sympathy,

urge to touch;

fragility

depression

Frustrator

Cautious;

distrustful

Uneasiness,

anger

Nonentity

Topic

shifting

Feeling

of being used, lack

of

recognition

To

understand transference, a counselor

must focus on client's

expectations, need for

advice, dependence,

trust

building, establishing contact

and getting behind client's

barriers.

Termination

of Counseling Relationships

�

Life

is a series of hellos and

goodbyes; hello begins at

birth and good-byes end at

death.

�

Refers

to the decision, one-sided or mutual, to

stop counseling (Burke,

1989)

�

A

formal termination serves

three functions:

o

Signals

that something is finished: Many

theorists assume that

termination will occur naturally

and

leave

both clients and counselors

pleased.

o

Termination

is a means of maintaining changes already

achieved and generalizing

problem-solving

skills

93

Theory

and Practice of Counseling -

PSY632

VU

Serves

as a reminder that the client has

matured. It indicates that the

counseling is finished and it

is

o

time

for the client to face their

life challenges. The client

has matured and thinks

and acts more

effectively

and independently.

Termination

of a Session

There

is no great secret to ending sessions.

There are some

guidelines:

�

Start

and end on time.

�

Leave

5 minutes or so for a summary of the

session.

�

Introduce

the end of the session normally

("Our time is coming to a close").

�

Assign

homework.

�

Set

up next appointment.

�

Limit

the number of sessions.

Limiting

the number of sessions can facilitate

termination. Counselors and

client both are motivated by

the

knowledge

that the counseling experience is

limited in time.

Termination

of the Relationship

�

Termination

is the end of the professional relationship

with the client when the

session goals have

been

met.

�

Generally,

both client and counselor

should give each other verbal messages

about a readiness to

terminate.

�

It is

wise to spend the final 3-4

weeks discussing termination in a

relationship lasting more than 3

months

(Hackney & Cormier, 1994).

�

One-sixth

of the time spent in a counseling relationship should

be devoted to focusing on termination

(Shulman,

1979). For example, if there

are total 18 sessions, 3 can

be devoted to mentioning about

termination.

�

Two

ways to facilitate the ending (Dixon &

Glover, 1984):

o

Fading is

gradual decrease reinforcement for

behaving in certain ways.

o

To

help client develop successful

problem-solving skills.

94

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION:Counseling Journals, Definitions of Counseling

- HISTORICAL BACKGROUND COUNSELING & PSYCHOTHERAPY

- HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 1900-1909:Frank Parson, Psychopathic Hospitals

- HISTORICAL BACKGROUND:Recent Trends in Counseling

- GOALS & ACTIVITIES GOALS OF COUNSELING:Facilitating Behavior Change

- ETHICAL & LEGAL ISSUES IN COUNSELING:Development of Codes

- ETHICAL & LEGAL ISSUES IN COUNSELING:Keeping Relationships Professional

- EFFECTIVE COUNSELOR:Personal Characteristics Model

- EFFECTIVE COUNSELOR:Humanism, People Orientation, Intellectual Curiosity

- EFFECTIVE COUNSELOR:Cultural Bias in Theory and Practice, Stress and Burnout

- COUNSELING SKILLS:Microskills, Body Language & Movement, Paralinguistics

- COUNSELING SKILLS COUNSELOR’S NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION:Use of Space

- COUNSELING SKILLS HINTS TO MAINTAIN CONGRUENCE:

- LISTENING & UNDERSTANDING SKILLS:Barriers to an Accepting Attitude

- LISTENING & UNDERSTANDING SKILLS:Suggestive Questions,

- LISTENING & UNDERSTANDING SKILLS:Tips for Paraphrasing, Summarizing Skills

- INFLUENCING SKILLS:Basic Listening Sequence (BLS), Interpretation/ Reframing

- FOCUSING & CHALLENGING SKILLS:Focused and Selective Attention, Family focus

- COUNSELING PROCESS:Link to the Previous Lecture

- COUNSELING PROCESS:The Initial Session, Counselor-initiated, Advice Giving

- COUNSELING PROCESS:Transference & Counter-transference

- THEORY IN THE PRACTICE OF COUNSELING:Timing of Termination

- PSYCHOANALYTIC APPROACHES TO COUNSELING:View of Human Nature

- CLASSICAL PSYCHOANALYTIC APPROACH:Psychic Determination, Anxiety

- NEO-FREUDIANS:Strengths, Weaknesses, NEO-FREUDIANS, Family Constellation

- NEO-FREUDIANS:Task setting, Composition of Personality, The Shadow

- NEO-FREUDIANS:Ten Neurotic Needs, Modes of Experiencing

- CLIENT-CENTERED APPROACH:Background of his approach, Techniques

- GESTALT THERAPY:Fritz Perls, Causes of Human Difficulties

- GESTALT THERAPY:Role of the Counselor, Assessment

- EXISTENTIAL THERAPY:Rollo May, Role of Counselor, Logotherapy

- COGNITIVE APPROACHES TO COUNSELING:Stress-Inoculation Therapy

- COGNITIVE APPROACHES TO COUNSELING:Role of the Counselor

- TRANSACTIONAL ANALYSIS:Eric Berne, The child ego state, Transactional Analysis

- BEHAVIORAL APPROACHES:Respondent Learning, Social Learning Theory

- BEHAVIORAL APPROACHES:Use of reinforcers, Maintenance, Extinction

- REALITY THERAPY:Role of the Counselor, Strengths, Limitations

- GROUPS IN COUNSELING:Major benefits, Traditional & Historical Groups

- GROUPS IN COUNSELING:Humanistic Groups, Gestalt Groups

- MARRIAGE & FAMILY COUNSELING:Systems Theory, Postwar changes

- MARRIAGE & FAMILY COUNSELING:Concepts Related to Circular Causality

- CAREER COUNSELING:Situational Approaches, Decision Theory

- COMMUNITY COUNSELING & CONSULTING:Community Counseling

- DIAGNOSIS & ASSESSMENT:Assessment Techniques, Observation

- FINAL OVERVIEW:Ethical issues, Influencing skills, Counseling Approaches