|

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Lesson

42

INTERPERSONAL

POWER: LEADERSHIP

Aims:

�

To

understand main theories and types of leadership in the

light of current

research.

Objectives:

�

To

describe main theories of

leadership.

�

To

discuss different types of

leadership.

�

To

discuss recent research on gender

and leadership.

Leadership

The

leader of a group is the person who

has the most impact on group

behavior and beliefs. According

to

Pescosolido

(2001), the person who

exerts the most influence

and provides direction and

energy to the

group

is the leader this is the person who

initiates action, gives

orders, doles out rewards and

punishments,

settles

disputes between fellow members, and

pushes and pulls the group

toward its goals. Leaders

may be

appointed,

elected, or emerge over time.

Many groups have only one

leader; other groups have two or

more

individuals

with equally high levels of

influence. Generally, groups tend to have

multiple leaders as

their

tasks

become more diverse and

complex.

Theories

of leadership

The great-person

theory

The situational

perspective

The contingency

theory

The

great person theory

The

great-person theory of leadership suggests

that leaders possess

particular characteristics. This

perspective

on leadership maintains that some

people are born to lead

and others are born to

follow.

According

to this "trait" or "great

person" perspective, some people

are more clever or dominant

than

others,

so they rise to the top. This perspective

is based on anthropological studies,

that certain human

beings

also have traits that make

them "natural leaders." One such

trait is intelligence. In some groups,

the

leader

is more intelligent than his or her

followers (Bass & Avolio,

1993; Stogdill, 1948).

Intellectually

gifted

individuals often make very

successful leaders.

In

some studies of small groups, the

person who talked most

became the group leader (McGrath &

Julian,

1963).

Two other important traits

are a need for achievement and

being perceptive about other

people's

needs.

The best leaders seem to be

people who are both

strongly driven to succeed and

skillful at

maintaining

good relationships with

their followers.

�Stogdill's early (1948) and

later review (1974) of 163

studies from 1949-1970

showed that the

success of

a

leader is related to different

traits:

Intelligent

Need for achievement &

being perceptive about

others' needs

Strong interpersonal

skills

Confident

Optimistic

takes initiative in social

situations

The

Situational Perspective

A

second perspective on leadership holds

that the situation creates the

leader. According to

this

"situational"

perspective, the person who becomes a

group's leader is the one who happened to be in

the

right

place at the right time (Cooper &

McGaugh, 1969). Adolph

Hitler rose to power in

pre-World War II

Germany

because citizens who had suffered

military and economic collapse wanted the

most forceful

leader

they could find. Groups

frequently respond to crisis by choosing

a leader who in other

circumstances

179

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

might

be perceived as too authoritarian.

Situational factors as trivial as who

sits at the head of the table

can

also

affect who emerges as the

group leader (Howells & Becker,

1962).

Leadership

and talking:

Finally,

Situational factors affect who

talks the most in a group,

which in turn affects who

emerges as

leader.

In one study of talkativeness and leadership, four

college men held a group

discussion (Bavelas,

Hastorf,

Gross, & Kite, 1965).

After the discussion had ended, the four

men rated each other on

traits like

leadership.

The more the target man

talked, the higher he was rated on

leadership. In other words, a

purely

situational

factor, having nothing to do

with the man's own

personality, cast him in the

role of group leader.

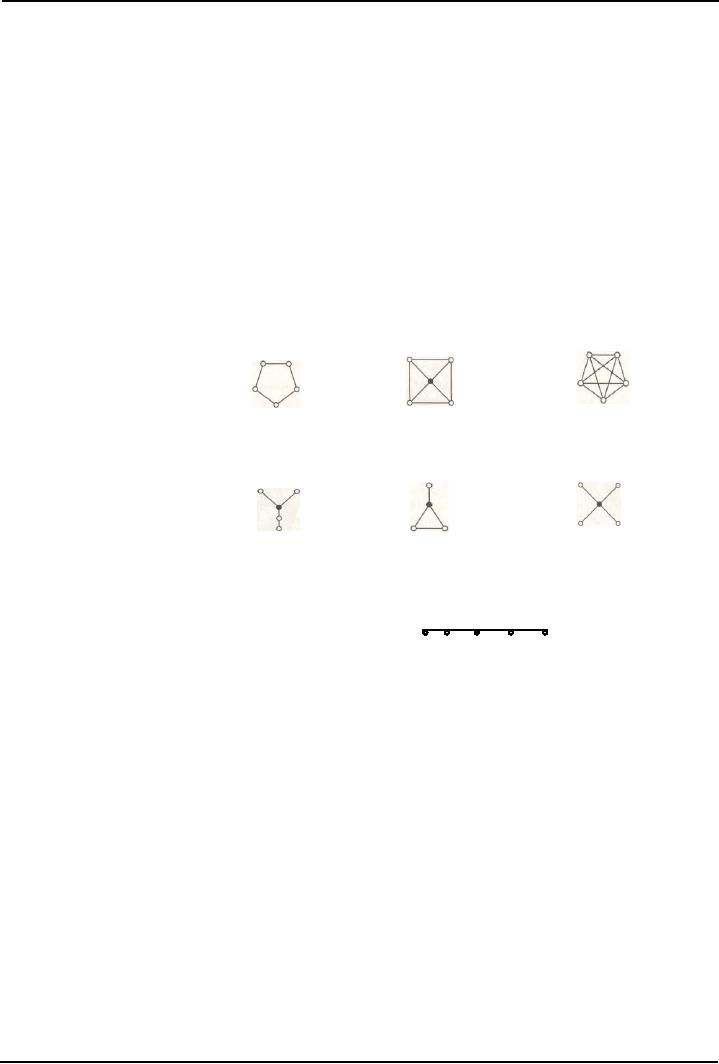

Communication

patterns:

�Communication pattern is another

situational factor that is

important in making a person

leader.

�Some groups (corporate & govt.

Bureaucracies) have formal, established patterns of

communications

�Several different

possible

group

communication

Communication

patterns:

networks:

people occupying

central

position emerge as

leaders

than peripheral

The

Contingency Theory of

Leadership

According

to the contingency

Circle

W

heel

All-channel

theory

of leadership, the

group

member who acts as

leader

is contingent, or

dependent,

on what the group

needs

to accomplish (Fiedler,

1964,

1967, 1971, 1993).

According

to the contingency

Y

or Yoke

Kite

Star

theory

of leadership, potential

leaders

differ in whether

they

are

task-oriented

or

Chain

relationship-oriented.

Task-

oriented

leaders concentrate

the

group's energies on the

task

at hand. They are impatient

with and intolerant of group

members who do not

contribute to the group

effort.

Relationship-oriented leaders, in contrast,

concentrate the group's energies on maintaining

cohesion,

harmony,

and cooperation. They tend

to get along well with subordinates, even

those who may not

be

contributing

as much as they might to a

particular group

effort.

To

identify these two leadership styles,

Fiedler developed the Least Preferred

Coworker Scale, which

asks

leaders

to evaluate the person in the group

they like least. Fiedler

found that leaders who

evaluated their

least

preferred coworker (LPC)

very negatively were primarily

motivated to attain successful

task

performance

and only secondarily motivated to

seek good interpersonal

relations among group

members.

These

low LPC leaders fit the

mold of the task-oriented

leader. In contrast, Fiedler found

that leaders who

evaluated

their LPCs positively were

primarily motivated toward

achieving satisfactory

interpersonal

relationships

among the group members and only

secondarily motivated to successfully complete

group

tasks.

These high LPC leaders

fit the mold of the relationship-oriented

leader.

Predicting

leader effectiveness

Who

makes the best leader-someone

who is task-oriented or someone

who is relationship-oriented?

According

to the contingency theory of leadership,

"it all depends (Fiedler

& Garcia, 1987). In

some

situations

a task-oriented leader is more effective. In

other situations, a relationship-oriented

leader is more

effective.

The determining factor is

how much control the leader

has. The leader's control

depends on three

factors:

the leader's relationship with the

group; the degree to which the group's

task is structured or well

180

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

defined;

and the leader's power to bestow rewards

or punishments. In "favorable" situations where

the

leader

has good relations with

subordinates, the task is well defined,

and the leader's power is

unquestioned,

a

task-oriented leader is best for

both group effectiveness and group

members' satisfaction. Interestingly,

a

task-oriented

leader is also best for

"unfavorable" situations, where the leader

has very poor relations

with

subordinates,

the task is very unstructured, and the leader

has little real power. A

relationship-oriented

leader

functions best, however, in the

"mid-range" situations where

leader-follower relations

are

moderately

good, the task is neither structured

nor unstructured, and the leader's

"legitimate" power is

moderate.

In

one test of contingency theory,

university administrators were identified as

either task-oriented or

relationship-oriented

(Chemers, Hays, Rhode-wait, &

Wysocki, 1985). Their jobs

wore classified as

low,

moderate,

or high in situational

control.

Task-oriented

leaders felt under the most

stress when their leadership

situation was uncertain--when

they

held

neither high nor low

situational control.

Relationship-oriented

leaders, in contrast, felt under the

greatest stress when they

had low rather than

moderate

control over the situation.

Task-oriented leaders also

reported far more stress-related

physical

illnesses

(such as angina pectoris, colitis, and

eczema) than did

relationship-oriented leaders in

moderate

situational

control jobs, whereas

relationship-oriented leaders reported

more stress-related illnesses in

low

situational

control jobs.

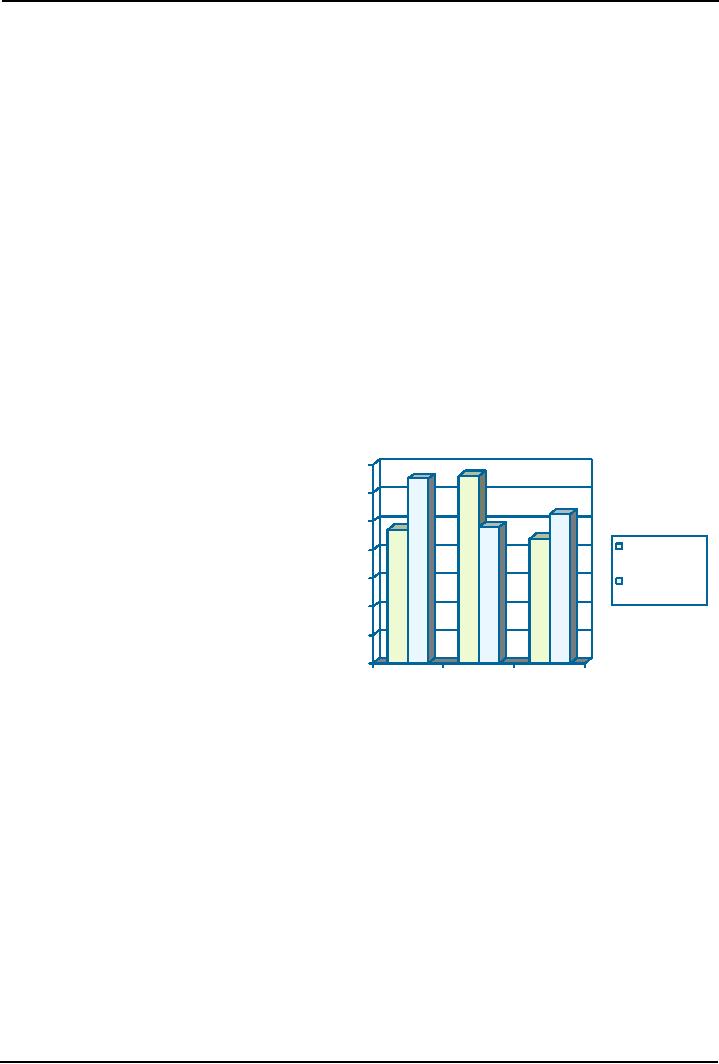

Figure

1: Leadership style & perception

of

situational

stress

70

Transformational

and

Transactional

60

leadership

50

�House (1976), Burns (1978),

Bass (1985)

linked

the need of leaders and followers in

an

Task

orient ed

40

interactive

process.

30

�Bass distinguished

transformational and

Relationship-

orient

ed

transactional

behaviour

20

�Transformational leaders

raises followers to

10

higher

levels of morality and

motivation

�Multifactor Leadership

Questionnaire was

0

Low

Moderat

e

High

developed

to measure transformational and

transactional

leadership (Bass & Avolio,

1989)

Transformational

Leaders Take Heroic and

unconventional Actions

One

of the earliest approaches to understanding leadership

was to search for person;

traits that caused

some

people

and not others to become

leaders. Unfortunately, few

leaf characteristics have been

identified.

Leaders

tend to be slightly more intelligent and

taller than nonleaders, are more

confident and adaptable,

and,

not surprisingly, have a higher

desire for power (Chemers et

al., 2000). They also

tend to be more

charismatic,

a quality that has prompted

a number of researchers to analyze the psychological

dynamics of

charismatic

or transformational

leaders.

Transformational

Leaders.

A

transformational leader changes--or

transforms--the outlook and behavior of

followers, which

allows

them

to move beyond their self-interests

for the good of the group or

society (Bass, 1997). Some

great

leaders

of the twentieth century inspired

tremendous changes in their respective

societies by making

supporters

believe that anything was

possible if they collectively worked

toward a common good

(as

defined

by the leader). The general view of

transformational leaders is that

they are "natural

born"

influence

agents who inspire high

devotion, motivation, and productivity in

group members.

Because

181

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

transformational

leaders often use

unconventional strategies that

put them at risk, it is not uncommon

for

them

to face severe physical

hardships--and even death--in moving the

group to its goals.

Survey,

interview, and experimental studies

suggest there are at least three

core components to

transformational

leadership (Kirkpatrick & Locke,

1996; Rai & Sinha,

2000).

1.

Ability to communicate a vision. A

vision, which is a future

ideal state embodying shared

group values,

is

the main technique that

transformational leaders use to

inspire followers. In communicating a

vision,

leaders

convey the expectation of high

performance among followers and a confidence

that they have the

ability

to reach the vision.

2.

Ability to implement a vision.

Transformational leaders use a

variety of techniques to implement

a

vision,

such as clarifying how task

goals are to be accomplished, serving as a

role model, providing

individualized

support, and recognizing accomplishments.

3.

Demonstrating a charismatic communication

style. Transformational leaders have a

captivating

communication

style, in which they make

direct eye contact, exhibit animated

facial expressions, and

use

powerful

speech and nonverbal

tactics.

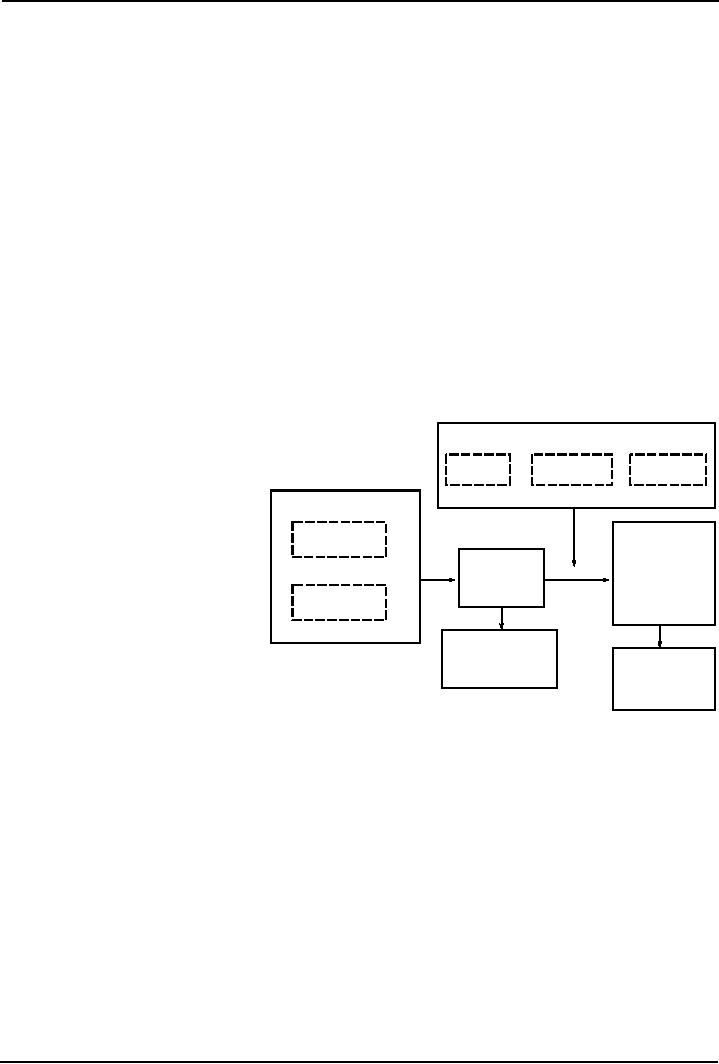

Subtypes

of Transformational leadership (as

measured by MLQ)

�Charismatic/idealised

influence:

role

model, respect, trust

Transformational

Leadership Model

�Inspirational

motivation

Bass

& Avolio (1994)

Provide

meaning, team's spirit,

commitment

to goals

Transf

or mat iona l

Leadership

�Intellectual

stimulation

To

be innovative and creative, no

Charisma

Individualised

Intellectual

+

+

Inspiration

Consideration

Stimulation

critique

of mistakes

Transact

ional Leadership

�Individual

consideration

coach/mentor,

two-way

Management

Heightened

-by-exception

communication

motivation

to

attain

+

Expected

designated

effort

Subtypes

of

Transactional

outcomes

Contingent

leadership

(extra

effort)

reward

�Contingent

reward

for

performance

Expected

Performance

performance

reasonably

effective

beyond

expectations

�Management

by

execption

(corrective)

active: monitor

deviance

passive: if supervising

large numbers of

subordinate

�Laissez faire:

non-transactional

decisions not made, action

delayed

responsibility

ignored

How

do leaders wield

power?

Winston

Churchill exerted considerable interpersonal

power in his letters to Roosevelt, in

which Churchill

tried

to bring the United States

into the war on Britain's side.

The letters contained six types

of

interpersonal

or social power that Churchill and

other leaders use: expert

power, referent power,

informa-

tional

power, legitimate power,

reward power, and coercive

power.

Six

types of leaders' power

1.

Expert

power comes

from having superior

knowledge or ability. Modern subordinates

in the

workplace

often do not have access to the

organization's plans and problems. Supervisors

wield

expert

power because they know

details of the organization

that subordinates do not

know.

182

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

2.

Referent

power involves

emphasizing a common identity. Churchill

always signed his letters to

Roosevelt

"Former Naval Person." Although

such a signature may seem

odd for the leader of the

British

Empire, it emphasized that

Churchill and Roosevelt had both

served their countries' navies.

Before

becoming president, Franklin Roosevelt

had served as U.S. Secretary of the

Navy.

Similarly,

modern workplace supervisors wield

referent power over subordinates by

making them

feel

like part of a team.

Referent power depends on

building a social identity.

3.

Information

power consists of

using arguments that are

logically compelling. When

Churchill

emphasized

the danger to the United States should

Britain be defeated, Roosevelt found

the

argument

very convincing.

4.

Legitimate

power is based on

social norms and obligations, especially

reciprocating when

someone

else has done you a favor.

Churchill first put

Roosevelt in his debt by

sharing military

secrets

that were vital to U.S.

interests. Then he emphasized

that Britain was sacrificing

to defend

the

United States and other countries

from subjugation.

5.

Reward

power comes

from ability to grant rewards.

Modern workplace supervisors also

use

reward

power selectively to accomplish their

goals. The person who

controls your promotions

and

pay

raises is in a good position to

demand obedience.

6.

Coercive

power involves a

threat of punishment.

When

the types are

used

The

higher in the organization a leader was

and the more people the leader supervised

directly or indirectly,

the

more the leader used threats of

punishment, promises of rewards, and

appeals to company loyalty to get

followers

to obey. Power affects a leader's choice of

influence tactics in settings as diverse

as industry and

psychotherapy

(Kipnis, 1984). Hitler and

his Nazis came to rely

almost exclusively on coercive

power.

Different

sex for different

tasks?

Women

are chosen as leaders by groups

that are pursuing "feminine"

tasks, whereas men are

chosen as

leaders

by groups that are pursuing

"masculine" tasks (Eagly &

Karau, 1991; Eagly et al.,

1994). According

to

the traditional stereotype, "feminine"

tasks include deciding how

to spend wedding money,

sewing

buttons

on a panel, and getting to know

other group members by sharing

feelings. "Masculine"

tasks

include

ranking the desirability of auto

accessories, repairing a machine, and

discussing how to survive in

a

disaster.

In other words, groups chose as leader a

person who is expected to have expert

power.

Unfortunately

for qualified women, most

business tasks seem

"masculine." When businessmen

and

businesswomen

in the United States describe the

ideal leader or the ideal manager, they

typically describe

someone

who acts like the male sex

role stereotype ancL-not someone

who acts like the female

sex role

stereotype

(Lord, DeVader, & Alliger,

1986). Subordinates perceive women

business executives, for

instance,

as having more of all six types of

power when the women wear a

jacket and "look like a

man"

than

when they do not. According

to traditional sex role

stereotypes, acting like a

man involves being

independent,

masterful, competent, and assertive,

whereas acting like a woman

involves being

friendly,

unselfish,

and concerned about other

people's feelings.

Reaction

to women as leaders

In

one study of how subordinates react to

male versus female leaders, groups of

four college students held

a

discussion

(Butler & Geis, 1990). The group's

goal was to rank how

important various items (for

example,

food,

a first-aid kit, water, a

compass, rope, a star map)

would be for surviving a

spaceship crash on

the

moon.

Only two of the four group

members (one man and one

woman) were actual participants. The

other

two

group members were confederates

who had studied all possible arguments

for and against each

survival

item. In some of the group

discussions, either the male or the

female confederate "took over"

and

started

leading the group. The "solo

leader," whether male or female,

directed the discussion and

provided

183

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

the

final rationale for each

group decision. The other

confederate, although he or she offered

good

suggestions,

adopted the role of "follower." In other

group discussions, the male and female

confederates

both

"took over." With their

greater preparation, the confederates were

easily able to direct and to

dominate

the

discussion and the group's decisions. When the

discussion ended, the experimenters asked

participants

to

rate each other's

competence. The participants

did not display sex

bias by rating female

leaders as less

competent

than male leaders. The experimenters

suspected, though, that

participants might be biased

with-

out

being aware of it. During

the discussion, the experimenters placed observers

behind one-way mirrors

to

record

the facial expressions of participants.

According to these observers,

whose ratings agreed with

each

other,

participants betrayed their

true feelings by smiling and

nodding agreement whenever the

male

confederate

"took charge" and by frowning and

tightening their facial

muscle whenever the

female

confederate

"took charge." Also, when

participants were later asked to

describe each other's

personality

traits,

both men and women described the

female solo leader as bossy and

excessively dominating. When

she

talked more than everyone

else and forced the group to be

task-oriented, which she had to do to

become

a

solo leader, the female solo

leader violated sex role expectations and

"earned" the condemnation of

other

group

members.

Reading:

�

Franzoi,

S. (2003). Social Psychology.

Boston: McGraw-Hill. Chapter

10.

Other

Readings:

�

Lord,

C.G. (1997). Social

Psychology. Orlando: Harcourt

Brace and Company. Chapter 8.

�

David

G. Myers, D. G. (2002). Social

Psychology (7th ed.). New

York: McGraw-Hill.

�

Taylor,

S.E. (2006). Social

Psychology (12th ed.). New York: Prentice

Hall.

184

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Readings, Main Elements of Definitions

- INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Social Psychology and Sociology

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Scientific Method

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Evaluate Ethics

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY RESEARCH PROCESS, DESIGNS AND METHODS (CONTINUED)

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY OBSERVATIONAL METHOD

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY CORRELATIONAL METHOD:

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY EXPERIMENTAL METHOD

- THE SELF:Meta Analysis, THE INTERNET, BRAIN-IMAGING TECHNIQUES

- THE SELF (CONTINUED):Development of Self awareness, SELF REGULATION

- THE SELF (CONTINUE…….):Journal Activity, POSSIBLE HISTORICAL EFFECTS

- THE SELF (CONTINUE……….):SELF-SCHEMAS, SELF-COMPLEXITY

- PERSON PERCEPTION:Impression Formation, Facial Expressions

- PERSON PERCEPTION (CONTINUE…..):GENDER SOCIALIZATION, Integrating Impressions

- PERSON PERCEPTION: WHEN PERSON PERCEPTION IS MOST CHALLENGING

- ATTRIBUTION:The locus of causality, Stability & Controllability

- ATTRIBUTION ERRORS:Biases in Attribution, Cultural differences

- SOCIAL COGNITION:We are categorizing creatures, Developing Schemas

- SOCIAL COGNITION (CONTINUE…….):Counterfactual Thinking, Confirmation bias

- ATTITUDES:Affective component, Behavioral component, Cognitive component

- ATTITUDE FORMATION:Classical conditioning, Subliminal conditioning

- ATTITUDE AND BEHAVIOR:Theory of planned behavior, Attitude strength

- ATTITUDE CHANGE:Factors affecting dissonance, Likeability

- ATTITUDE CHANGE (CONTINUE……….):Attitudinal Inoculation, Audience Variables

- PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION:Activity on Cognitive Dissonance, Categorization

- PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION (CONTINUE……….):Religion, Stereotype threat

- REDUCING PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION:The contact hypothesis

- INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION:Reasons for affiliation, Theory of Social exchange

- INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION (CONTINUE……..):Physical attractiveness

- INTIMATE RELATIONSHIPS:Applied Social Psychology Lab

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE:Attachment styles & Friendship, SOCIAL INTERACTIONS

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE (CONTINE………):Normative influence, Informational influence

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE (CONTINUE……):Crimes of Obedience, Predictions

- AGGRESSION:Identifying Aggression, Instrumental aggression

- AGGRESSION (CONTINUE……):The Cognitive-Neo-associationist Model

- REDUCING AGGRESSION:Punishment, Incompatible response strategy

- PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR:Types of Helping, Reciprocal helping, Norm of responsibility

- PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE………):Bystander Intervention, Diffusion of responsibility

- GROUP BEHAVIOR:Applied Social Psychology Lab, Basic Features of Groups

- GROUP BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE…………):Social Loafing, Deindividuation

- up Decision GROUP BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE……….):GroProcess, Group Polarization

- INTERPERSONAL POWER: LEADERSHIP, The Situational Perspective, Information power

- SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN COURT

- SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN CLINIC

- FINAL REVIEW:Social Psychology and related fields, History, Social cognition