|

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Lesson

37

PROSOCIAL

BEHAVIOR

Aims

To

introduce psychological aspects of

prosocial behaviour

Objectives

Describe

different types of helping

behavior

�

Discuss

different explanations of helping

behavior: Why do we

help?

�

Evaluate

the Bystander Intervention

Model

Prosocial

Behavior: Chapter Summary

This

chapter discusses the basics of helping

behavior. Altruism is distinguished

from prosocial

behavior.

Several

theoretical perspectives on helping

are considered. These include the

evolutionary perspective; the

socio-cultural

perspective (focusing on social norms of

responsibility, reciprocity, social

justice); the

learning

perspective (modeling and reinforcement);

Latan� and Darley's decision-making

perspective

(perceiving

a need, taking personal responsibility,

weighing the costs and benefits,

deciding to help and

taking

action); and attribution theory's

perspective (focusing on our willingness

to help those who deserve

help

because we attribute their problems to

causes out of their

control). Factors that

influence a potential

helper's

likelihood of actually helping

are considered, including mood,

empathy and personal distress,

personality

characteristics, and gender. More

specific situational factors that

influence the decision to

help

are

also discussed, including the bystander

effect (and explanations for

it), environmental conditions,

and

time

pressures.

Definitions

All

of us have experience of helping and being

helped by others. Sometime our prosocial

behavior involves

little

cost, while on other times it

involves money, effort, or

time. Two kinds of helping

behavior exist with

different

motives. Nineteenth century

philosopher Auguste Comte maintained

that egoistic help is based

on

egoism;

in which the person wants

something in return. On the other hand

altruistic help is for

another

person's

welfare. Prosocial, egoistic and

altruistic behaviors are

distinguished below from

each other:

Prosocial

Behavior: Voluntary

behavior that is carried out

to benefit another person

Egoistic

helping: A form of

helping in which the ultimate

goal of the helper is to increase

one's own

welfare

Altruistic

helping means

helping someone when there is no

expectation of a reward

Types

of Helping (McGuire,

1994)

�

Casual

help, e.g., giving

directions

�

Substantial

help, e.g., lending

money

�

Emotional

help, e.g., listening

�

Emergency

help, e.g., saving someone,

helping in crisis

Explanations

of helping behavior: Why do we

help?

�

An

Evolutionary perspective

�

A

Sociocultural Perspective: Norms of

reciprocity, social responsibility, social

justice

�

A

Learning Perspective

152

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Helping

is Consistent with Evolutionary

Theory

Sometime

we help for some personal

gain, while on other times

we help without any personal

motive. Not

only

human beings, but many examples of

prosocial behavior have been observed

among animal species,

e.g.,

dolphins, lions, chimpanzees,

etc. One principle of

evolutionary theory is that

any social behavior

that

enhances

reproductive success (the

conception, birth, and survival of

offspring) will continue to be

passed

on

from one generation to the next.

However, to reproduce, an animal must

first survive. Taken

together,

there

may be mechanisms for the

genetic transmission of helpful

inclinations from generation to

generation.

Evolutionary

theorists contend that it is not only

personal survival that is important.

Rather it is a gene

survival

that promotes reproductive

fitness.

"Kin

selection"

provides an explanation for

gene survival:

�

There

is a preference for helping blood

relatives because this will

increase the chances for

the

helper's

genes to pass on to successive

generations. Because your blood

relatives share many

of

your

same genes, by promoting

their survival you can

also preserve your genes

even if you don't

survive

the helpful act. This

principle of kin selection

states

that you will exhibit

preferences for

helping

blood relatives because this

will increase the odds that

your genes will be

transmitted to

subsequent

generations.

�

Animals

help others more who are

genetically related.

But

People also help non-relatives.

How this becomes possible?

This is explained by Trivers

(1983) in the

next

perspective on prosocial behavior

explanations.

A

Socio-cultural Perspective: Social

Norms

Reciprocal

helping:

According

to this principle, people

are likely to help strangers

if it is understood that the recipient

is

expected

to return the favor at some

time in future. Trivers

(1983) believes that

reciprocal helping is

most

likely

to evolve in a species when

certain conditions exist.

Three of these conditions

are:

�

Social

group living, so that

individuals have ample opportunity to

give and receive

help.

�

Mutual

dependence, in which species

survival depends on cooperation,

and

�

The

lack of rigid dominance hierarchies, so

that reciprocal helping will

enhance each animal's

power.

Considerable

research supports both kin

selection and reciprocal helping among

humans and other animals.

For

example, when threatened by predators, squirrels

are much more likely to warn

genetically related

squirrels

with which they live

than unrelated squirrels or

those from other areas.

Similarly, across a

wide

variety

of human cultures, relatives receive more

help than non-relatives,

especially if the help

involves

considerable

costs, such as being a

kidney donor (Borgida et

al., 1992). Reciprocal

helping is also common

in

humans, and, consistent with

evolutionary-based mechanisms to prevent

cheating, when people

are

unable

to reciprocate, they tend to experience

guilt and

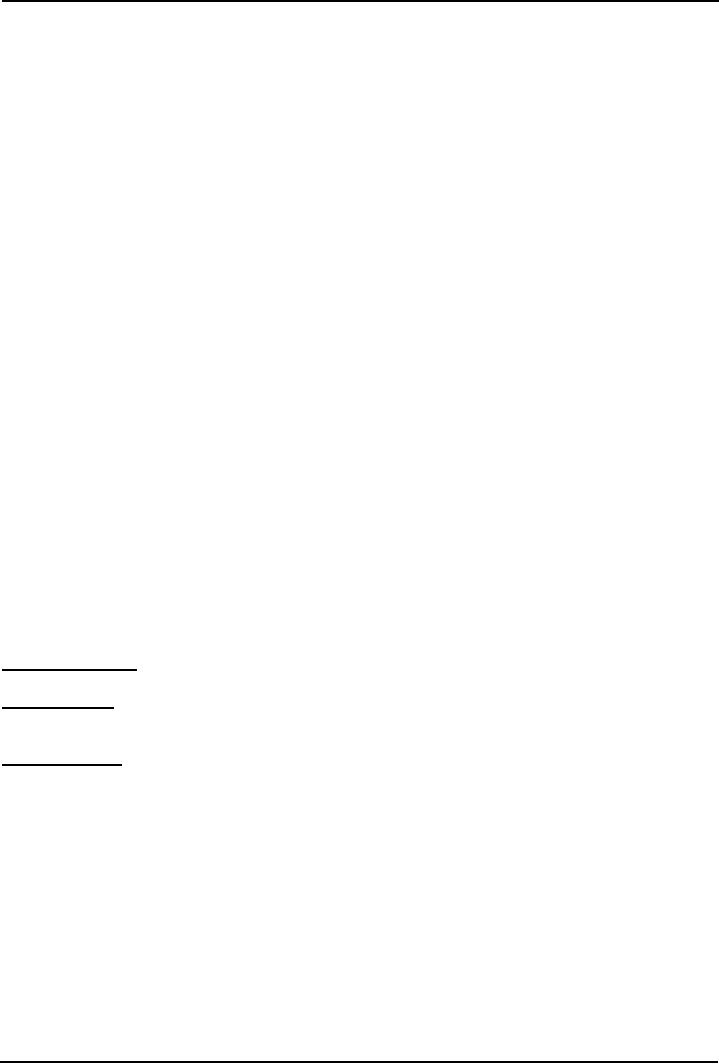

Figure

1 illustrates the power

of

reciprocity:

shame.

Three

social norms that serve as

guidelines for

prosocial

behavior

deal

with

reciprocity,

responsibility,

and justice. The first of

these prosocial

norms,

the norm of reciprocity, is based

on

maintaining

fairness in social relationships. This

norm

prescribes

that people should be paid

back for

whatever

they give us. This

norm also explains

the

discomfort

that people typically experience

when they

receive

help but cannot give something back in

return.

Norm

of responsibility:

In

comparison to the reciprocity norm, the

other two

153

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

prosocial

norms dictate that people

should help due to a greater awareness of

what is right. For instance,

the

norm

of social responsibility states

that we should help when

others are in need and dependent on

us.

Acting

on this norm, adults feel responsible

for the health and safety of

children, teachers have a sense

of

duty

and obligation to their students, and

police and fire-fighters believe

they must help even at the

risk of

their

own lives. This social

responsibility norm requires help-givers

to render assistance regardless of

the

recipient's

worthiness and without an expectation of

being rewarded.

Norm

of social justice:

In

contrast to the dependent-driven social

responsibility norm, the norm

of social justice stipulates

that

people

should help only when

they believe that others

deserve assistance. People become

entitled to the

deserving

label by either possessing

socially desirable personality

characteristics or by engaging in

socially

desirable

behaviors. Thus, according to the social

justice norm, if "good"

people encounter unfortunate

circumstances,

they deserve our help

and we have a duty to render

assistance.

A

Learning Perspective

Observational

learning in children:

According

to social learning theorists, observational

learning or modeling can

influence the development of

helping

in at least two ways (Rosenkoetter,

1999; Rushton, 1980). First, it

can initially teach children

how

to

engage in helpful actions. Second, it

can show children what is

likely to happen when they

actually

engage

in helpful (or selfish)

behavior. In this learning

process, what models say and

what they do both

shape

the observers' prosocial behaviors.

For example, in one study,

sixth-grade girls played a

game to win

chips

that could be traded for

candy and toys (Midlarsky et

al,, 1973). Prior to

actually playing, each of

the

girls

watched a woman play the game. In the

charitable condition, the adult

put some of the chips she

won

into

a jar labeled "money for

poor children" and then

urged the girl to think

about the poor children

who

would

"love to receive the prizes these chips

can buy." In the selfish

condition, the adult model

also urged

the

child to donate chips to the poor

children, but she did so

after putting all her chips

into a jar labeled

"my

money."

Results indicated a clear effect of

prosocial modeling. Girls

who had observed the

charitable

model

donated more chips to the poor than those

who had seen the selfish

model.

Prosocial

modeling in adults:

Modeling

prosocial behavior is not

confined to children. In one

study conducted in a natural

setting,

motorists

who simply saw someone

helping a woman change a

flat tire were more likely to

later stop and

assist

a second woman who was in a

similar predicament (Bryan & Test,

1967). In another experiment

(Rushton

& Campbell, 1977), female

college students interacted

with a friendly woman as part of a

study

on

social interaction (this was

not the true purpose, and the

woman was a confederate of the

researchers).

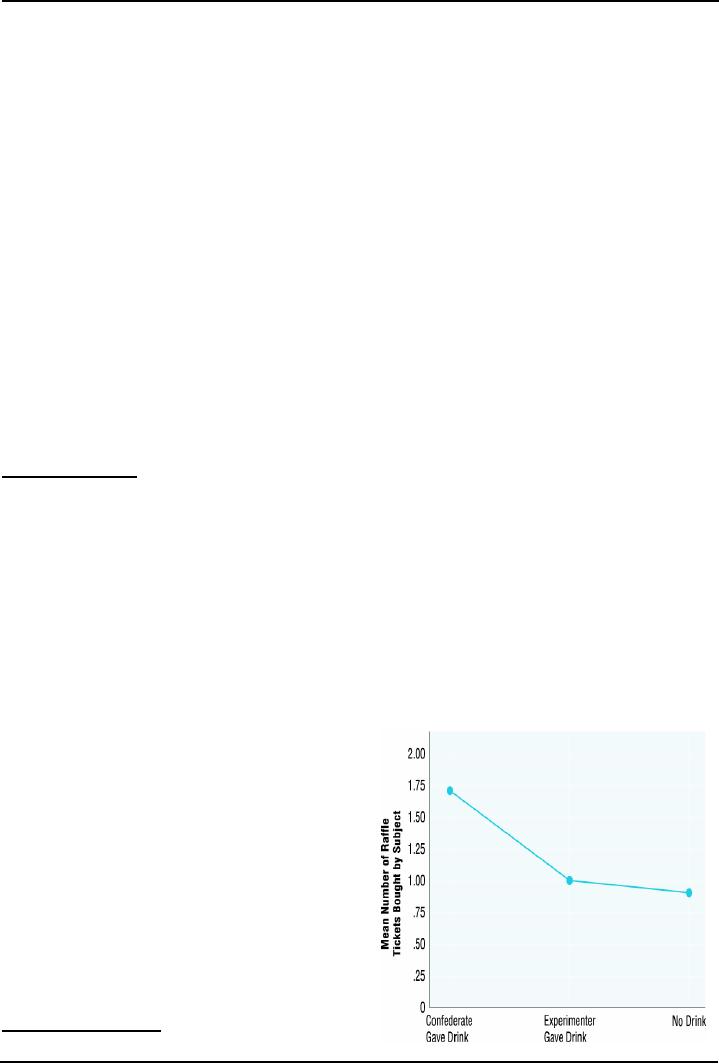

When

the fabricated study was completed, the

two women left the lab

together and passed a table

staffed by

people

asking for blood donations.

When participants were asked

first, only 25% agreed, and

none actually

followed

through on their pledge six

weeks later. However, when

the confederate was asked first

and

signed

up to donate blood, 67% of the

participants also agreed to

give blood, and 33% actually

fulfilled

their

commitment.

Modelling

helping behaviour

Figure

2 more clearly illustrates the findings

of this

study:

70

Rewarding

prosocial behavior:

60

Although

observing the prosocial actions of others

can

50

shape

children's and adults' own helping,

the

40

consequences

of their actions will often

determine

30

whether

they continue to engage in

prosocial behavior.

20

Social

rewards, such as praise, are generally

more

effective

reinforcers than material rewards,

such as

10

money

(Grusec, 1991). In one such

experiment

0

Participant

asked

Confederate

conducted

by Rushton and Goody Teachman

(1978),

first

asked

first

154

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

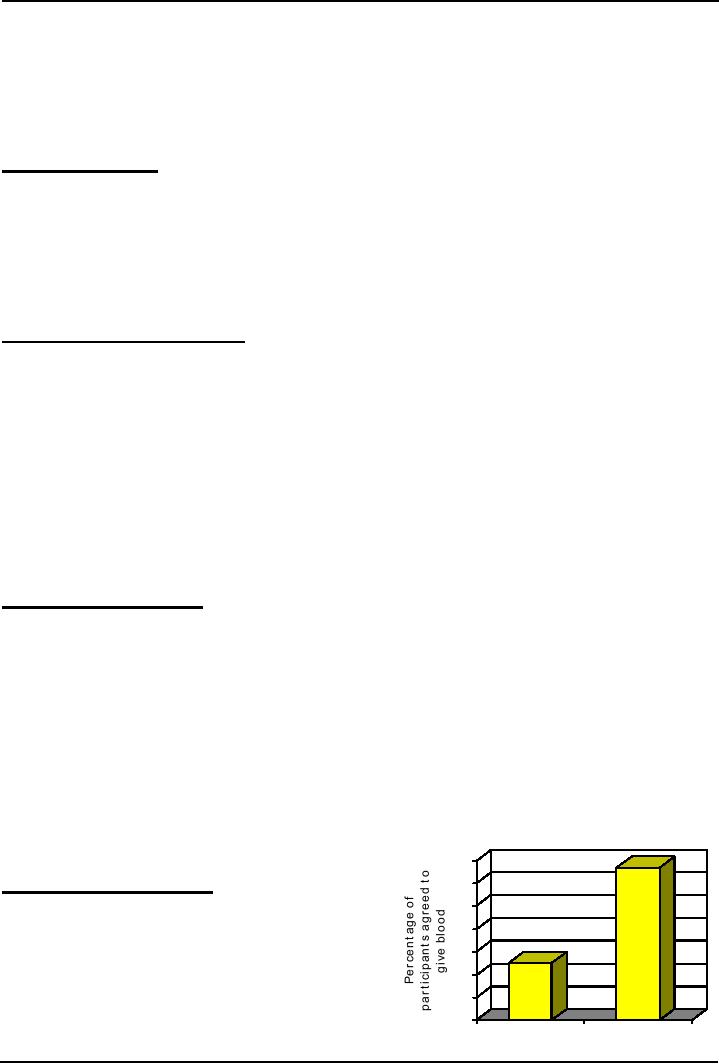

children

were first induced to behave generously

by having generosity modeled to them as

in the previously

described

game-token studies. When the

children donated some of their

winnings to an orphan

named

Bobby,

the model either praised the child

for his or her imitative

generosity (reward condition) by

saying

"Good

for you, that's really

nice of you," or scolded the

child (punishment condition) by

saying "That's

kind

of silly for you to give to

Bobby. Now you will have

fewer tokens for yourself."

There was also a

no-

reinforcement

condition in which the adult

said nothing. As you can

see in figure 3, children

who were

praised

gave more to Bobby on later trials

than did children who were

scolded. The effects of being

either

rewarded

or punished for prosocial behavior were

so strong that they still

influenced how much

the

children

gave to Bobby two weeks

later. The results are

demonstrated in Figure

3 as

given below:

Another

study demonstrates that

verbal praise or

scolding

by an adult model can either

strengthen or

weaken

children's level of generosity

(Moss & Page,

1972).

In the reward condition, the woman

asking for

directions

rewarded her helper by saying, "Thank

you

very

much, I really appreciate this." In contrast, in

the

punishment

condition the woman responded to

help by

saying,

"I can't understand what you're

saying, never

mind,

I'll ask someone else."

Researchers found

that

when

people were rewarded by the first woman,

90%

of

them helped the second woman.

However, when

punished

by the first woman, only 40%

helped in the

later

situation. As in the study with

children, this adult

study

suggests that people's future decisions

to help

are

often influenced by the degree to

which current helpful

efforts are met by praise or

rebuke.

When

do we help?

On

March 13, 1964, Kitty

Genovese was stabbed

on

her

way back to home. A man stabbed her

with knife

near

her apartment building in New York at

3.20 a.m.

Her

cries rang out in the night

but nobody came

for

help

while at least 38 of her neighbors were

watching

from

the windows. The apathy of her

neighbors was

the

topic of news stories, and

people's dinner

conversations.

Two people who discussed the

murder

at

length were social psychologists John Darley

and

Bibb

Latane.

Bystander

intervention model eventually

emerged as a

result

of these dinner

discussions.

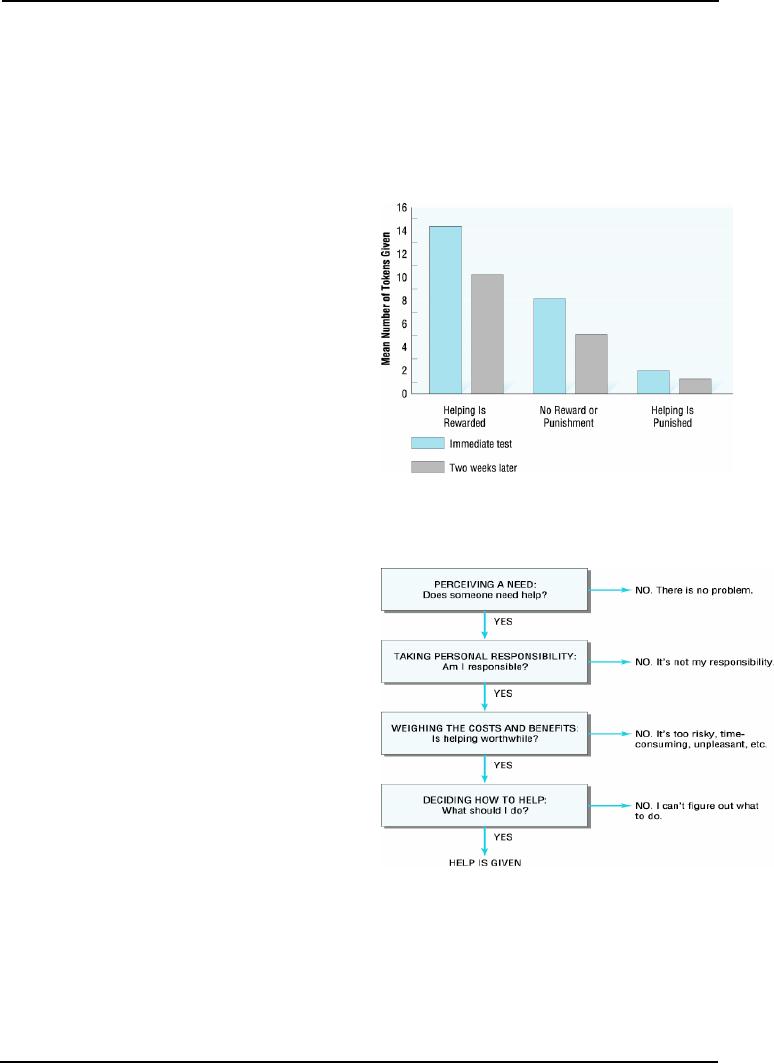

Bystander

intervention involves a series

of

decisions

Although

people often see people in

need of help, they

sometimes

don't go and offer it themselves. People

decide whether or not to offer

assistance based on a

variety

of perceptions and evaluations. Help is

offered only if a person

answers "yes" at each step.

The

bystander

intervention model maintains

that there are four stages

which must be gone through

before

helping

occurs.

As

it can be seen in Figure 4

given below that at each

point in this five-step

process, one decision results

in

no

help being given, while the

other decision takes the bystander

one step closer to

intervention.

155

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

The

first thing that you, as a

potential helper, must do is

notice that something unusual is

happening.

Unfortunately,

in many social settings, countless sights

and sounds flood our senses.

Because it is

impossible

to attend to all this stimuli, and

because we may be preoccupied with

something else, a cry

for

help

could conceivably go completely

unnoticed. This stimulus

overload effect is more likely to occur

in

densely

populated urban environments

than in rural settings (Milgram,

1970). Indeed, it is one of the

likely

reasons

why there is a negative correlation

between population density and helping

(Levine, 2003).

Another

reason is that sometimes it is

difficult to notice things

out of the ordinary as what is unusual in

one

setting

may be a normal occurrence in

another. As a bystander to an emergency, if you do

indeed notice

that

something unusual is happening you move

to the second step in the decision-making

process: deciding

whether

something is wrong and help

is needed. Returning to the previous

example, if you pass by

an

unconscious

man on the sidewalk you may

ask yourself, "Did he suffer

a heart attack or is he merely

sleeping.

When you define the

situation as an emergency, the bystander intervention

model states that

the

third

decision you must make is

determining the extent to which

you have responsibility to help.

According

to

Latane and Darley, one

factor that may play a

role in your decision to

help or not is whether

an

appropriate

authority figure is nearby. Let's

continue this hypothetical emergency

situation, but now

imagine

that there is no police car in

sight. Faced with the

reality of a clear emergency, you still

may not

help

if you convince yourself

that all the other motorists

watching this incident could

help just as well as

you.

The presence of these other

potential helpers, like the presence of

authority figures, may cause

you to

feel

less personally responsible for

intervening.

If,

however, you assume

responsibility for helping, a

fourth decision you must

make is the appropriate form

of

assistance to render. But in the

heat of the moment, what if you

are not sure what to do? You

may

become

paralyzed with uncertainty

about exactly how to render

assistance.

Finally,

if you notice something unusual,

interpret it as an emergency, assume

responsibility, and decide

how

to help, you still must

decide whether to implement your

course of prosocial

action.

Reading

�

Franzoi,

S. (2003). Social

Psychology. Boston:

McGraw-Hill. Chapter 14.

Other

Readings

�

Lord,

C.G. (1997). Social

Psychology. Orlando:

Harcourt Brace and Company. Chapter

8.

�

David

G. Myers, D. G. (2002). Social

Psychology (7th ed.).

New York:

McGraw-Hill.

�

Taylor,

S.E. (2006). Social

Psychology (12th ed.). New York: Prentice

Hall.

156

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Readings, Main Elements of Definitions

- INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Social Psychology and Sociology

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Scientific Method

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Evaluate Ethics

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY RESEARCH PROCESS, DESIGNS AND METHODS (CONTINUED)

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY OBSERVATIONAL METHOD

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY CORRELATIONAL METHOD:

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY EXPERIMENTAL METHOD

- THE SELF:Meta Analysis, THE INTERNET, BRAIN-IMAGING TECHNIQUES

- THE SELF (CONTINUED):Development of Self awareness, SELF REGULATION

- THE SELF (CONTINUE…….):Journal Activity, POSSIBLE HISTORICAL EFFECTS

- THE SELF (CONTINUE……….):SELF-SCHEMAS, SELF-COMPLEXITY

- PERSON PERCEPTION:Impression Formation, Facial Expressions

- PERSON PERCEPTION (CONTINUE…..):GENDER SOCIALIZATION, Integrating Impressions

- PERSON PERCEPTION: WHEN PERSON PERCEPTION IS MOST CHALLENGING

- ATTRIBUTION:The locus of causality, Stability & Controllability

- ATTRIBUTION ERRORS:Biases in Attribution, Cultural differences

- SOCIAL COGNITION:We are categorizing creatures, Developing Schemas

- SOCIAL COGNITION (CONTINUE…….):Counterfactual Thinking, Confirmation bias

- ATTITUDES:Affective component, Behavioral component, Cognitive component

- ATTITUDE FORMATION:Classical conditioning, Subliminal conditioning

- ATTITUDE AND BEHAVIOR:Theory of planned behavior, Attitude strength

- ATTITUDE CHANGE:Factors affecting dissonance, Likeability

- ATTITUDE CHANGE (CONTINUE……….):Attitudinal Inoculation, Audience Variables

- PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION:Activity on Cognitive Dissonance, Categorization

- PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION (CONTINUE……….):Religion, Stereotype threat

- REDUCING PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION:The contact hypothesis

- INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION:Reasons for affiliation, Theory of Social exchange

- INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION (CONTINUE……..):Physical attractiveness

- INTIMATE RELATIONSHIPS:Applied Social Psychology Lab

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE:Attachment styles & Friendship, SOCIAL INTERACTIONS

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE (CONTINE………):Normative influence, Informational influence

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE (CONTINUE……):Crimes of Obedience, Predictions

- AGGRESSION:Identifying Aggression, Instrumental aggression

- AGGRESSION (CONTINUE……):The Cognitive-Neo-associationist Model

- REDUCING AGGRESSION:Punishment, Incompatible response strategy

- PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR:Types of Helping, Reciprocal helping, Norm of responsibility

- PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE………):Bystander Intervention, Diffusion of responsibility

- GROUP BEHAVIOR:Applied Social Psychology Lab, Basic Features of Groups

- GROUP BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE…………):Social Loafing, Deindividuation

- up Decision GROUP BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE……….):GroProcess, Group Polarization

- INTERPERSONAL POWER: LEADERSHIP, The Situational Perspective, Information power

- SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN COURT

- SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN CLINIC

- FINAL REVIEW:Social Psychology and related fields, History, Social cognition