|

INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION (CONTINUE……..):Physical attractiveness |

| << INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION:Reasons for affiliation, Theory of Social exchange |

| INTIMATE RELATIONSHIPS:Applied Social Psychology Lab >> |

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Lesson

29

INTERPERSONAL

ATTRACTION (CONTINUE........)

Aims

To

introduce the concept of interpersonal

attraction and related

concepts

Objectives

�

To

describe the characteristics of others as

important factors in interpersonal

attraction.

�

To

discuss the situations when social

interaction becomes

problematic

Characteristics

of others & attraction

The

following characteristics of others have

been involved in interpersonal

attraction:

�

Physical

attractiveness

�

Similarity

�

Desirable

personal attributes

Physical

attractiveness

Despite

the old sayings that "beauty is

only skin deep" and "you

can't judge a book by its

cover", We tend

to

operate according to Aristotle's

2000-year-old pronouncement that

"personal

beauty is a greater

recommendation

than any letter of

introduction."

Research

on physical attractiveness

stereotype

What

is beautiful is good:

In

one of the first studies of the physical

attractiveness stereotype, Karen

Berscheid, and Elaine

[Walster]

Hatfield

(1972) asked college

students to look at pictures of men and

women who either were

good-

looking,

average, or homely and to then evaluate

their personalities. Results

indicated that the

students

tended

to assume that physically

attractive persons possessed a

host of socially desirable personality

traits

relative

to those who were unattractive.

This physical attractiveness effect

has also been documented

in

Hollywood

movies. Steven Smith and his coworkers

(1999) asked people to watch

the 100 most popular

movies

between 1940 and 1990 and to evaluate the

movies' main characters. Consistent with

the physical

attractiveness

stereotype, beautiful and handsome

characters were significantly more likely

to be portrayed

as

virtuous, romantically active, and

successful than their less

attractive counterparts. Over the

past thirty-

five

years, many researchers have

examined this stereotype, and

two separate meta-analyses of

these

studies

reveal that physically

attractive people are

perceived to be more sociable, successful,

happy,

dominant,

sexually warm, mentally

healthy, intelligent, and socially

skilled than those who

are unattractive

(Eagly

et al., 1991; Feingold

1992).

Cross-cultural

differences:

Although

these findings are based

solely on samples from

individualist cultures, the

physical

attractiveness

stereotype also occurs in collectivist

cultures, but its content is a bit

different.

Research

with children:

The

positive glow generated by

physical attractiveness is not reserved

solely for adults. Attractive

infants

are

perceived by adults as more likable, sociable,

competent, and easy to care

for than unattractive

babies

(Casey

& Ritter, 1996).

Attractiveness

and job-related

outcomes:

Field

and laboratory studies conducted in both

individualist and collectivist cultures

indicate that

physical

attractiveness

does have a moderate impact in a

variety of job-related outcomes,

including hiring,

salary,

116

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

and

promotion decisions. In one representative study,

Irene Frieze and her coworkers (1991)

obtained

information

on the career success of more than

700 former MBA graduates of

the 1973 to 1982 classes

at

the

University of Pittsburgh. They

also judged former students'

facial attractiveness based on photos

taken

during

their final year in school.

Results indicated that there

was about a $2,200

difference between the

starting

salaries of good-looking men and

those with slow average

faces. For women, facial

attractiveness

did

not influence their starting

salaries, but it did

substantially impact their

later salaries. Once

hired,

women

who were above average in facial

attractiveness typically earned $4,200

more per year than

women

who

were below average in attractiveness. For

attractive and unattractive

men, this difference in

earning

power

per year was $5,200.

Further, although neither

height nor weight affected a

woman's starting

salary,

being

20% or more overweight reduced a

man's starting salary by more than

$2,000. Overall, the

research

literature

informs us that physical

appearance does indeed

influence success on the

job.

Obesity

and attractiveness

bias:

�

People

who are obese are

stigmatized and face discrimination in

the workplace.

�

The

negative view occurs because

people are seen as responsible

for their weight.

�

Anti-fat

prejudice is strongest in individualistic

cultures (Crandall et al.,

2001).

Who

is Attractive?

Culture

plays a large role in

standards of attractiveness. However,

people do tend to agree on

some features

that

are seen as more

attractive:

�

Statistically

"average" faces

�

Symmetrical

or balanced faces

Taking

into consideration all the cross-cultural

research, it appears that -

all things being equal--men

prefer

women

with relatively low

waist-to-hip ratios because

this body type signifies

youth, fertility, and

current

non-pregnancy.

However, in environments where people

face frequent food

shortages, male preference

shifts

to a higher female waist-to-hip

ratio because this body

type signifies greater ability to

both produce

and

nurse offspring when food is

scarce.

Beyond

body type, there is also evidence

that there may be universal

standards of

facial attractiveness. For

example,

a number of studies indicate that we

prefer faces in which right

and left sides are

well matched or

symmetrical

(Chen

et al., 1997; Mealey et al.,

1999). Facial symmetry was

one thing that Lucy

Grealy's

plastic

surgeons tried unsuccessfully to restore

in countless operations (see lecture 28

for reference).

Evolutionary

psychologists contend that we refer

facial symmetry because

symmetry generally indicates

physical

health and the lack f

genetic defects,

Besides

symmetry influencing attractiveness,

studies of people's perceptions of young

men and women's

individual

faces and composite faces

(computer-generated "averages" of all the

individual faces),

indicate

that

what people judge most

attractive are faces that

represent the "average" face in the

population

(Langlois

et al., 1994). This tendency to

define physical attractiveness

according to the "average rule"

has

been

found in many cultures (Jones &

Hill, 1993; Pollard,

1995).

Evolutionary

psychologists further contend that,

besides symmetry and averageness,

youthfulness and

maturity

figure into facial attractiveness

judgments. Consistent with this

hypothesis, a number of studies

have

found that possessing

youthful or slightly immature

facial

features (large eyes, small

nose, full lips,

small

chin, delicate jaw) enhances

female attractiveness, while possessing

mature

facial

characteristics

related

to social dominance, broad forehead,

thick eyebrows, thin lips,

large jaw) increases

the

attractiveness

of males (Cunningham, 1986; Johnston

& Franklin, 1993).

Why

does attractiveness

matter?

�

People

believe attractiveness is correlated with

other positive characteristics

(consistent with

implicit

personality theory).

�

Being

associated with an attractive

other leads a person to be

seen as more attractive him or

herself.

�

According

to evolutionary theory, attractiveness

may provide a clue to health

and reproductive

fitness.

117

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Is

the attractiveness stereotype

accurate?

Alan

Feingold (1992b) conducted a meta-analysis of more

than ninety studies that

investigated whether

physically

attractive and physically

unattractive people actually

differed in their basic

personality traits.

His

analysis

indicated no significant relationships

between physical attractiveness and such

traits as

intelligence,

dominance, self-esteem, and mental

health.

Birds

of a feather really do flock

together: Similarity

Social

Psychological research generally

indicates that we are attracted to those

who are similar to

us.

Demographic

similarity:

Research

on high school friendships found

that students identified

their best friends as those

who were

similar

to them in sex, race, age, and

year in school.

Attitudinal

similarity:

In

Newcomb's boardinghouse study (as

mentioned previously), similarity in

age and family background

not

only

influenced interpersonal attraction,

but similarity in attitudes

also provided mutual liking,

Unlike

physical

and demographic characteristics, it generally

takes lime to learn another

person's attitudes. In

laboratory

studies, Dorm Byrne and

his colleagues accelerated the

getting-acquainted process by

having

participants

complete attitude questionnaires and later

"introducing" them to another person by

having

them

read his or her responses to a

similar questionnaire (Byrne &

Nelson, 1965; Schoneman et

al., 1977).

The

researchers had actually filled

out the questionnaire so that the

answers were either similar

or

dissimilar

to the participants' own attitudinal

responses. The results

showed that the participants

expressed

much

stronger liking when they

thought they shared a greater

percentage of similar attitudes

with the

individual.

This finding is important,

for it suggests that

the

proportion of similar

attitudes is more

important

than the actual number

of

similar attitudes. Thus, we should be

more attracted to someone who

agrees

with us on four of six topics

(66 percent similarity) than

one with whom we share

similar opinions

on

ten of twenty-five topics (40 percent

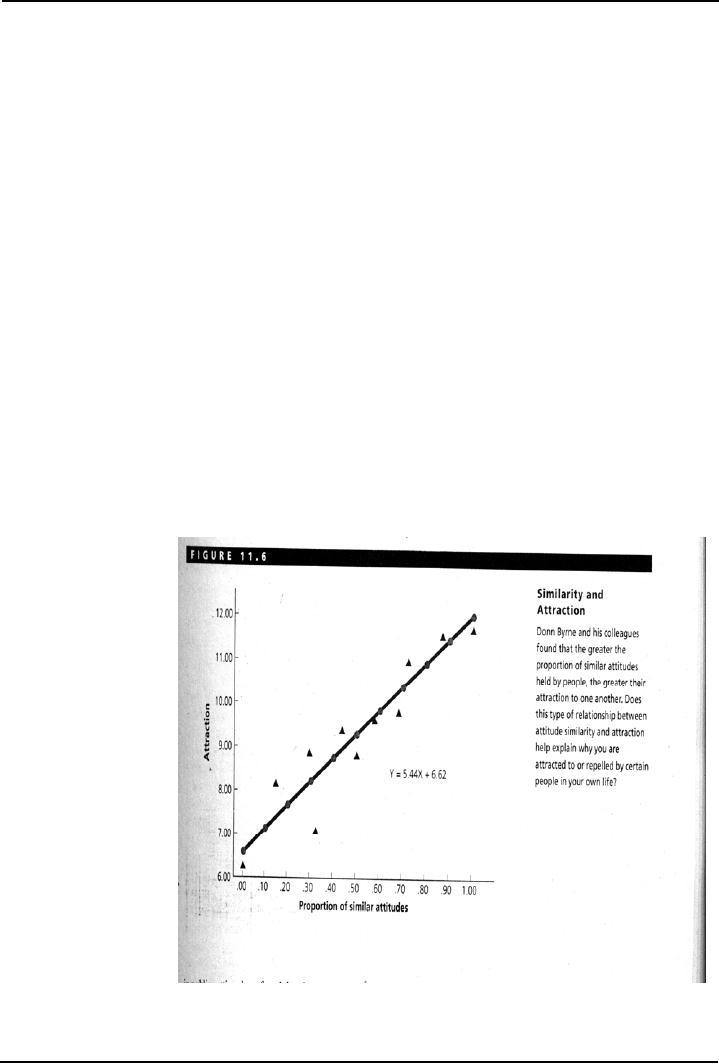

similarity). The graph given

below describes more clearly

the

relationship

between attitude similarity and

attraction.

Similarity

in physical

attractiveness:

In

fact, researchers who

have

observed couples

in

public settings have

found

that they

are

remarkably

well

matched

in physical

attractiveness

(Feingold,

1988). One

possible

reason why

we

are

attracted to potential

romantic

partners who

are

similar to us in

physical

attractiveness

is

that we estimate they

have

about the same

social

exchange value

as

us.

This

tendency to be

attracted

to others who

are

similar to us in particular

characteristics, such as physical

attractiveness, is known as the matching

hypothesis,

and

it appears to be a socially shared

belief (Stiles et al.,

1996). We expect that people

who

118

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

have

similar levels of physical attractiveness

will be more satisfied as couples

than those who are

phys-

ically

mismatched.

Desirable

Personal Attributes

�

Warmth

o

People

appear warm when they have a

positive attitude and

express liking, praise,

and

approval.

Nonverbal

behaviors such as smiling, attentiveness,

and expressing emotions also

o

contribute

to perceptions of warmth.

�

Competence

o

We

like people who are

socially skilled, intelligent,

and competent.

The

type of competence that

matters most depends on the nature of the

relationship., e.g.,

o

social

skills for friends,

knowledge for professors

will be preferred. However,

being "too

perfect"

can be off-putting

When

social interaction becomes

problematic

Whenever

we approach others, we

risk rejection. Even

if others do accept

our

social

overtures, there is the further possibility

that we may commit a social

blunder that

will

cause them to form a negative impression

of us.

Social

anxiety can keep us isolated

from others

Social

anxiety is the unpleasant

emotion we experience due to our

concern with interpersonal

evaluation

(Leary

& Kowalski, 1995). This

anxiety is what causes us to

occasionally (or frequently)

avoid social

interaction.

We can experience social anxiety even

when alone: simply

anticipating social interaction is

often

sufficient to arouse

it.

The

unfortunate consequence of social

anxiousness is that it can

trap a person into

increasingly unpleasant

social

exchanges (DePaulo et al.,

1990). Highly socially

anxious people anxiously expect,

readily perceive,

and

intensely react to rejection

cues in their surroundings (Downey et

al., 2004). For example,

they are

more

attentive to faces with

negative expressions than

they are to those with

positive or neutral

expressions

(Pishyar

et al., 2004). This

attentional bias in noticing

negative social feedback results in

highly anxious

persons

often acting in ways--avoiding eye

contact, appearing nervous and jittery--that

fulfill the self-

prophecy

(Pozo et al., 1991).

Defining

and measuring loneliness

Loneliness

is

defined as having a smaller or less

satisfying network of social and

intimate relationships

than

we desire (Green et al.,

2001).

Age,

gender, culture and

loneliness

Numerous

studies have identified the

young--adolescents and young adults--as

the loneliest age groups

(Peplau

et al., 1982), As people mature and

move beyond the young adult

years, their loneliness

tends to

decrease

until relatively late in

life, when factors such as

poor health and the death of loved

ones increase

social

isolation (Green et al.,

2001). One reason why

adolescents and young adults may be

lonelier than

older

individuals is that young

people face many more social

transitions, such as falling in and

out of love

for

the first time, leaving

family and friends, and training

and

searching

for a full-time job--all of

which

can

cause loneliness (Oswald &

Clark, 2003).

There

are clear age differences in

loneliness, but gender differences

are not as clear-cut. Some

studies have

found

a slight tendency for women to

report greater loneliness than

men, yet other studies

fail to find any

differences

at all (Archibald et al.,

1995; Brage et al., 1993). Despite

any firm evidence for

gender

differences

in the degree

of

loneliness, there does appear to be

evidence that men and women

feel lonely

119

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

for

different reasons. Men tend

to feel lonely when deprived

of group interaction; women

are more likely to

feel

lonely when they lack

one-to-one emotional sharing (Stokes

&

Levin,

1986).

Social

skills deficits and

loneliness

Similar

to the negative consequences of social

anxiousness, chronically lonely

people often think

and

behave

in ways that reduce their

likelihood of establishing new and

rewarding relationships. Studies

conducted

with college students

illustrate some of these

self-defeating patterns of behavior.

Typically, in

these

investigations, students who

are strangers to one another are

asked to briefly interact in

either pairs or

groups,

after which they rate

themselves and their partners on

such interpersonal dimensions as

friendliness,

honesty, and openness, Compared with

individuals, nonlonely college

students rate themselves

negatively

following such laboratory

interactions. They perceive

themselves as having been

less friendly,

less

honest and open, and less

warm (Christensen & Kashy, 1998;

Jones et al., 1983). They

also expect

those

who interact with them to

perceive them in this negative

manner. This expectation of

failure in social

interaction

appears all the more hopeless to the

chronically lonely because

they believe that improving

their

social

life is beyond their control

(Duck et al., 1994).

Reading

�

Franzoi,

S. (2003). Social

Psychology. Boston:

McGraw-Hill. Chapter 11.

Other

Readings

�

Lord,

C.G. (1997). Social

Psychology. Orlando:

Harcourt Brace and Company. Chapter

8.

�

David

G. Myers, D. G. (2002). Social

Psychology (7th ed.).

New York:

McGraw-Hill.

120

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Lesson

30

INTIMATE

RELATIONSHIPS

Aims

To

introduce the concept of intimate

relationships, attachment styles and later

adult relationships

Objectives

To

discuss what is

intimacy?

To

describe how self concepts

of important others are manifested in

one's own self

schemas

To

discuss attachment as an adaptive

response

To

describe link between different

attachment styles & later adult

relationships:

To

discuss attachment styles and romantic

relationships as well as

friendships

Applied

Social Psychology

Lab

In

the previous lecture, it was

pointed out that social

skill deficit is likely

cause of loneliness, which is

the

primary

reason of low self esteem.

Applied social Psychology Lab

exercise highlights the

appropriate

social

skills, as mentioned below,

required for interpersonal

interaction.

Amount

of personal attention given to one's

partner in interaction

Ability

to recognize and conform to social

norms

Regulating

one's mood prior to commencing

social interaction

Training

includes observation, modeling,

role playing, observing

one's own interaction on

videotape,

speaking

on phone, giving compliments, actively

listening, etc.

Research

has indicated that

participation in this kind of

training shows improvement in social

skills and an

increased

level of social satisfaction (Erwin,

1994).

Student's

Activity

In

the following exercise, you are to

think of one person who is a

close friend, and another person

who you

know

fairly well but whom

you believe you are

unlikely to become close to.

After you have decided on the

people

who will be rating, first

rate yourself on whether or not

you have each of the characteristics

listed by

placing

a check on the line for each

characteristic that describes you.

Then do the same thing for

your close

friend

and for your acquaintance.

Traits

Self

Close

friend

Acquaintance

/

Non-Friend

Outgoing

Soft-Hearted

Organized

Creative

Independent

Conscientious

Quiet

Tough-minded

Efficient

Calm

Practical

Adventurous

Trusting

Passive

Generous

121

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Readings, Main Elements of Definitions

- INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Social Psychology and Sociology

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Scientific Method

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Evaluate Ethics

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY RESEARCH PROCESS, DESIGNS AND METHODS (CONTINUED)

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY OBSERVATIONAL METHOD

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY CORRELATIONAL METHOD:

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY EXPERIMENTAL METHOD

- THE SELF:Meta Analysis, THE INTERNET, BRAIN-IMAGING TECHNIQUES

- THE SELF (CONTINUED):Development of Self awareness, SELF REGULATION

- THE SELF (CONTINUE…….):Journal Activity, POSSIBLE HISTORICAL EFFECTS

- THE SELF (CONTINUE……….):SELF-SCHEMAS, SELF-COMPLEXITY

- PERSON PERCEPTION:Impression Formation, Facial Expressions

- PERSON PERCEPTION (CONTINUE…..):GENDER SOCIALIZATION, Integrating Impressions

- PERSON PERCEPTION: WHEN PERSON PERCEPTION IS MOST CHALLENGING

- ATTRIBUTION:The locus of causality, Stability & Controllability

- ATTRIBUTION ERRORS:Biases in Attribution, Cultural differences

- SOCIAL COGNITION:We are categorizing creatures, Developing Schemas

- SOCIAL COGNITION (CONTINUE…….):Counterfactual Thinking, Confirmation bias

- ATTITUDES:Affective component, Behavioral component, Cognitive component

- ATTITUDE FORMATION:Classical conditioning, Subliminal conditioning

- ATTITUDE AND BEHAVIOR:Theory of planned behavior, Attitude strength

- ATTITUDE CHANGE:Factors affecting dissonance, Likeability

- ATTITUDE CHANGE (CONTINUE……….):Attitudinal Inoculation, Audience Variables

- PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION:Activity on Cognitive Dissonance, Categorization

- PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION (CONTINUE……….):Religion, Stereotype threat

- REDUCING PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION:The contact hypothesis

- INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION:Reasons for affiliation, Theory of Social exchange

- INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION (CONTINUE……..):Physical attractiveness

- INTIMATE RELATIONSHIPS:Applied Social Psychology Lab

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE:Attachment styles & Friendship, SOCIAL INTERACTIONS

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE (CONTINE………):Normative influence, Informational influence

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE (CONTINUE……):Crimes of Obedience, Predictions

- AGGRESSION:Identifying Aggression, Instrumental aggression

- AGGRESSION (CONTINUE……):The Cognitive-Neo-associationist Model

- REDUCING AGGRESSION:Punishment, Incompatible response strategy

- PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR:Types of Helping, Reciprocal helping, Norm of responsibility

- PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE………):Bystander Intervention, Diffusion of responsibility

- GROUP BEHAVIOR:Applied Social Psychology Lab, Basic Features of Groups

- GROUP BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE…………):Social Loafing, Deindividuation

- up Decision GROUP BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE……….):GroProcess, Group Polarization

- INTERPERSONAL POWER: LEADERSHIP, The Situational Perspective, Information power

- SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN COURT

- SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN CLINIC

- FINAL REVIEW:Social Psychology and related fields, History, Social cognition