|

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Lesson

18

SOCIAL

COGNITION

Aims

To

acquaint students with the

concept of social cognition and cognitive

misers in making sense of

their

social

world.

Objectives

�

To

understand the dual process of social

cognition

�

To

describe how do we organize and

make sense of social information

through social

categorization

and schemas.

�

To

discuss what shortcuts

stretch our cognitive

resources.

What

is Social Cognition?

Social

cognition is the way we analyse, remember, and

use information about the social

world (Berkowitz

&

Devine, 1995)

Social

cognition focuses on

the way we use this

information to arrive at coherent

judgments.

Dual-Process

models of social cognition:

strategies

�

Explicit

cognition: Deliberate judgments or decisions of

which we are consciously

aware

�

Implicit

cognition: Judgments or decisions that

are under the control of

automatically activated

evaluations

How

do we organize and make

sense of social

information

Usually

we make quick impression of people based

on minimal information available and we

do not have

luxury

of engaging in detailed impression.

Luckily then we come

equipped with alternative social

strategies

that

rely on implicit cognition. To

make sense of our social

world, we categorize things, and

develop

theories

(schemas) of how the social world

operates.

We

are categorizing creatures

�

A

mental grouping of objects, ideas, or

events that share common

properties is known as

category

concepts

�

Categories

are building blocks of

cognitions

�

Bruner,

Goodnow, & Austin (1956)

indicated that category membership is

determined via

defined

features,

i.e., an animal with three

body divisions, six legs, an

external skeleton, and a

rapid

reproductive

system = INSECT. If one or more of

these attributes is missing the animal

is

something

else.

�

Expands

our ability to deal with the

huge amount of information

Social

categorization (Hampson, 1988)

�

The

classification of people into groups

based on their common

attributes

�

Usually

done on the basis of readily apparent

physical features: sex, age,

and race; primary

categories

for human beings (Schneider, 2004);

special for evolutionary and

socio-cultural reasons

�

BUT...many

categories have uncertain or `Fuzzy'

boundaries (Rosch, 1978) and do not

fit in with a

strict

classification system.

73

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

�

Category

refers to features that characterize the

most typical (McGarry,

1999).

�

Prototypes

are the most representative members of a

category (Barsalou,

1991).

�

Categorization

of less typical members may

be slower/errorful because they

are less available

(male

nurses).

�

Correct

categorization depends on how

similar a given instance is to the

prototype, e.g., the

prototype

of the category `engineers' is a male

which may lead to errors in

categorization when

encountering

a female engineer. Similarly the

prototype of a "nurse" fits

well with a female.

Developing

Schemas

�

We

not only mentally group

objects, ideas, or events into

categories, but we also develop

theories

about

these categories, called

schemas.

�

A

schema

is

an organized, structured set of

cognitions about a concept.

�

Event

schemas are known as

scripts.

�

Schemas

are often called stereotypes

when applied to members of a social

group

�

Schemas

can be about particular

people, social roles, groups, or common

events.

�

People

are good or bad in certain

schemas, like someone's computer

schema may not be

good.

Advantages

of Schematic Processing

�

Schemas

Aid Information Processing

�

Schemas

Aid Recall

�

Schemas

Speed Up Processing

�

Schemas

Aid Automatic Inference

�

Schemas

Add Information

�

Schemas

Aid Interpretation

�

Schemas

Provide Expectations

�

Schemas

Contain Affect

What

shortcuts stretch our

cognitive resources: The

cognitive miser?

�

Processing

resources are valuable so we

engage in timesaving mental

shortcuts when trying

to

understand

the social world (Fiske & Taylor,

1991)

�

Timesaving

mental shortcuts, called heuristics,

reduce complex judgements to simple

rules-of-

thumb

(Tversky & Kahneman, 1974)

�

Advantages

of using cognitive miser are: 1. quick

social judgement and, 2. reasonable

accuracy

�

Quick

and easy - but can result in

biased information processing

(Ajzen, 1996)

A.

The Representativeness

Heuristic

�

The

tendency to judge the category membership of

people based on how closely

they match the

prototypical

member of that category.

There is an old saying that

"It looks like a duck, it

quakes

like

a duck, then it is probably a

duck"

�

One

important qualifying information is

base rates

�

Importance

of personal descriptions vs. base-rate

information: study by Tversky &

Kahneman

(1973)

where they told the research

participants that an imaginary

named Jack had been

selected

from

a group of 100 people. Some

were told that 30 were engineer and

others were told that 70

of

100

were engineers. Half of them were given a

description of jack that

either fit the omen

stereotype

of an engineer or did not.

Then they were asked to

guess the probability that

Jack was an

engineer.

The results showed that

when participants received

only importance related to

base rates,

they

were more likely to guess that he

was an engineer, but when

they received information

about

jack's

personality, they tended to ignore the

base-rate information. This tendency is

known as base-

rate

fallacy.

74

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

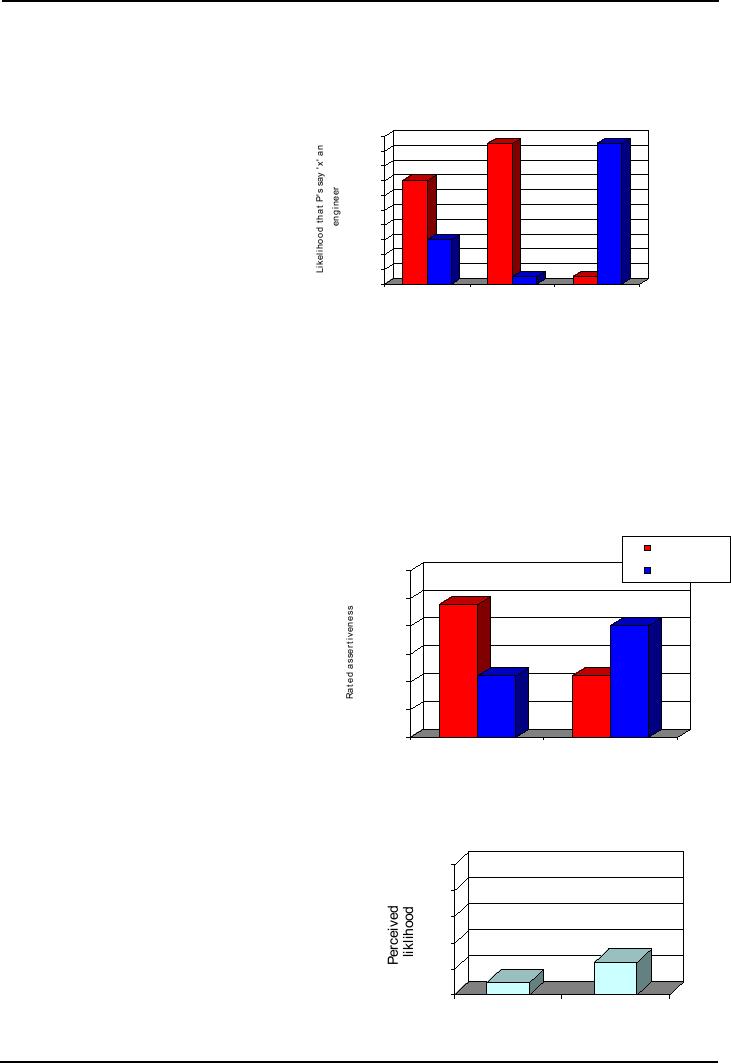

Figure

1 illustrates this study.

S

tu d y o f T v e rs k y & K a h n e m a n

(1

9 7 3 )

B.

The Availability

Heuristic

The

tendency to judge the

frequency

or probability of an

100

event

in terms of how easy it

is

90

to

think of examples of

that

80

70

event

(accessibility, Tversky &

60

Kahneman

(1973), e.g., plane

50

crashes.

40

30

20

Study

of Schwarz et al.

(1991)

10

0

�

Recall

12 (cognitively

Ba

s e r a t e in fo

Ba

s e ra t e in fo + Ba s e ra t e in fo +

re

p re s e n t a t iv e un r e p re s e n t a t iv e

difficult)

vs. 6 (cognitively

d

e s c r ip t io n

d

e s c r ip t io n

easy)

examples of assertive and unassertive

behaviour

�

Rate

assertiveness

�

People

attend to the difficulty of retrieving

instances of certain behaviours rather

than just the

content

Figure

2 illustrates this

study

C.The

Anchoring & adjustment

Heuristic

R

a t e d a s s e r t iv e n e s s fo llo w in g r e t r ie v a l o

f

�

Anchoring

is the tendency to be biased

a

s s e r t iv e b e h a v io u r s

towards

the starting value or anchor in

6

it e m s

making

quantitative judgements

7

1

2 it e m s

�

In

a survey study Plous (1989)

asked

6

.5

one

of the following questions from

the

respondents:

6

1.

Is there a greater than 1%

5

.5

chance

of a nuclear war

occurring

soon? (10%), OR

5

2.

Is there less than a

90%

4

.5

chance

of a nuclear war

4

occurring

soon? (25%)

A

s s e r t iv e b e h a v io u r

U

n a s s e r t iv e

b

e h a v io u r

Estimated

chances of a nuclear

The

results of this study are

illustrated in Figure

3

war

100

Reading

3.

Franzoi, S. (2003). Social

Psychology.

80

Boston:

McGraw-Hill. Chapter 5.

60

40

25

20

10

0

>1%

<90%

Anchor

75

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Readings, Main Elements of Definitions

- INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Social Psychology and Sociology

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Scientific Method

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Evaluate Ethics

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY RESEARCH PROCESS, DESIGNS AND METHODS (CONTINUED)

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY OBSERVATIONAL METHOD

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY CORRELATIONAL METHOD:

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY EXPERIMENTAL METHOD

- THE SELF:Meta Analysis, THE INTERNET, BRAIN-IMAGING TECHNIQUES

- THE SELF (CONTINUED):Development of Self awareness, SELF REGULATION

- THE SELF (CONTINUE…….):Journal Activity, POSSIBLE HISTORICAL EFFECTS

- THE SELF (CONTINUE……….):SELF-SCHEMAS, SELF-COMPLEXITY

- PERSON PERCEPTION:Impression Formation, Facial Expressions

- PERSON PERCEPTION (CONTINUE…..):GENDER SOCIALIZATION, Integrating Impressions

- PERSON PERCEPTION: WHEN PERSON PERCEPTION IS MOST CHALLENGING

- ATTRIBUTION:The locus of causality, Stability & Controllability

- ATTRIBUTION ERRORS:Biases in Attribution, Cultural differences

- SOCIAL COGNITION:We are categorizing creatures, Developing Schemas

- SOCIAL COGNITION (CONTINUE…….):Counterfactual Thinking, Confirmation bias

- ATTITUDES:Affective component, Behavioral component, Cognitive component

- ATTITUDE FORMATION:Classical conditioning, Subliminal conditioning

- ATTITUDE AND BEHAVIOR:Theory of planned behavior, Attitude strength

- ATTITUDE CHANGE:Factors affecting dissonance, Likeability

- ATTITUDE CHANGE (CONTINUE……….):Attitudinal Inoculation, Audience Variables

- PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION:Activity on Cognitive Dissonance, Categorization

- PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION (CONTINUE……….):Religion, Stereotype threat

- REDUCING PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION:The contact hypothesis

- INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION:Reasons for affiliation, Theory of Social exchange

- INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION (CONTINUE……..):Physical attractiveness

- INTIMATE RELATIONSHIPS:Applied Social Psychology Lab

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE:Attachment styles & Friendship, SOCIAL INTERACTIONS

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE (CONTINE………):Normative influence, Informational influence

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE (CONTINUE……):Crimes of Obedience, Predictions

- AGGRESSION:Identifying Aggression, Instrumental aggression

- AGGRESSION (CONTINUE……):The Cognitive-Neo-associationist Model

- REDUCING AGGRESSION:Punishment, Incompatible response strategy

- PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR:Types of Helping, Reciprocal helping, Norm of responsibility

- PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE………):Bystander Intervention, Diffusion of responsibility

- GROUP BEHAVIOR:Applied Social Psychology Lab, Basic Features of Groups

- GROUP BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE…………):Social Loafing, Deindividuation

- up Decision GROUP BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE……….):GroProcess, Group Polarization

- INTERPERSONAL POWER: LEADERSHIP, The Situational Perspective, Information power

- SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN COURT

- SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN CLINIC

- FINAL REVIEW:Social Psychology and related fields, History, Social cognition