|

ATTRIBUTION ERRORS:Biases in Attribution, Cultural differences |

| << ATTRIBUTION:The locus of causality, Stability & Controllability |

| SOCIAL COGNITION:We are categorizing creatures, Developing Schemas >> |

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Lesson

17

ATTRIBUTION

ERRORS

Aims

Introduce

the basic concept of causal

judgment and errors involved in

this process

Objectives

�

Understanding

primary biases in attributions

fundamental attribution error,

actor-observer bias,

false

consensus effect, self-serving

attribution error, and ultimate

attribution error

�

Discussing

implication of attribution

errors

Biases

in Attribution

�

Kelley's

model is idealized to explain

causes of behaviour, but we

really are naive

scientists.

�

Although

people follow these rules

and deduce causality

logically in some circumstances, a number

of

attribution

biases and `errors' often

occur

�

Considerable

research suggests that there

are several prominent biases in the ways

we make causal

attributions

The

process of making causal attributions

entails several "biases."

First, attributers seem too

ready to

assume

that another person's traits

correspond with his or her

words and deeds. This

"correspondence

bias"

occurs because people

overlook situational constraints,

have unrealistic expectations

for what

other

people are willing and able

to do, overemphasize the

link between the person

and his or her

behavior,

and adjust their initial

attributions inaccurately when

they are "cognitively busy."

The

fundamental

attribution error is the

correspondence bias.

A.

The fundamental attribution

error

Ichheiser

(1940) maintained long time

ago that "In everyday life

interpreting individual behaviour in

the

light

of personal factors rather than in the light of

situational factors must be considered the

fundamental

source

of misunderstanding personality in our

time". More than 30 years

later, Ross (1977) renamed

this

tendency

to make internal rather than external

attributions for peoples'

behaviour. He maintained that

the

fundamental

attribution error is the tendency to overestimate the

impact of dispositional causes

and

underestimate

the impact of situational causes on

other person's behaviour. Ross and

his colleagues devised

a

simulated TV quiz game in

which students were randomly

assigned to serve as either quizmaster

or

contestants.

The quizmasters would ask 10

challenging but fair questions

from the contestants. The

results

showed

that observers and contestants

both rated the quizmasters as more

knowledgeable despite the

process

of random

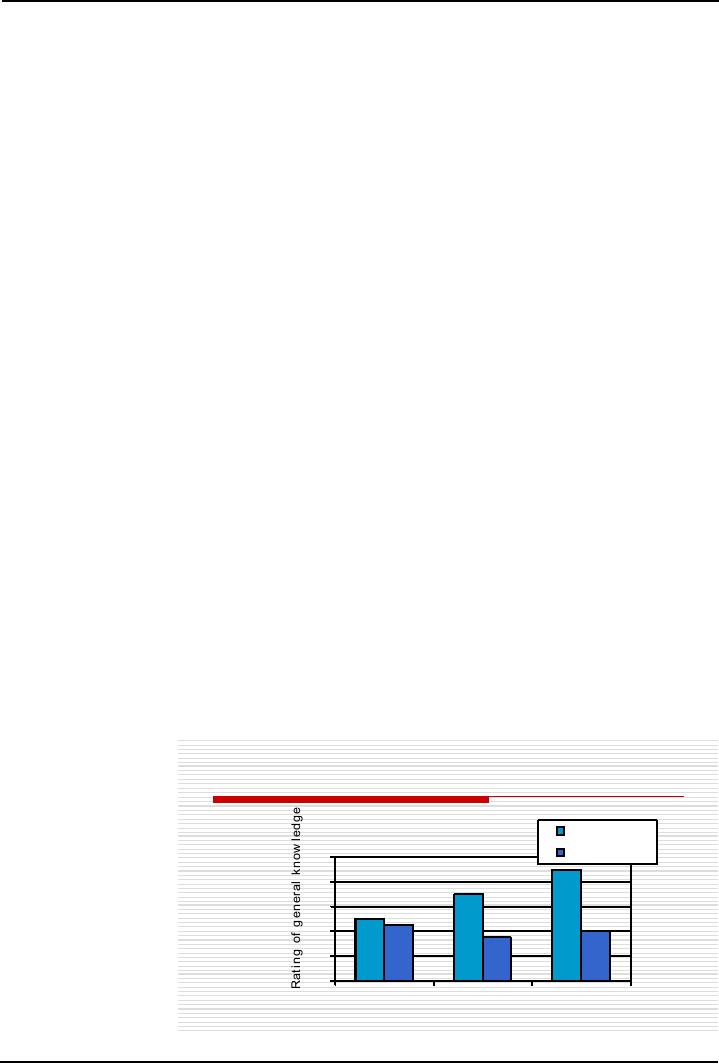

Fundamental

attribution error and

selection

for serving as

either

contestant or

TV

quiz game

quizmaster.

Figure 1

illustrates

this

Ross

et al. (1977)

experiment.

Quizmast

er

Cont

estant

10

Explanations

for the

8

fundamental

attribution

error

6

4

�

The

fundamental

2

attribution

error

0

may

occur because

Quizmaster

Contestant

Observer

people

make

ratings

ratings

ratings

dispositional

attributions

automatically

70

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

�

We

only later use situational

information

to discount it.

�

Predictability

Need: It gives us greater confidence

that we can accurately predict

behaviour

�

Perceptual

salience

The

person being observed is the most

perceptually salient aspect of the

situation (i.e., moving,

talking,

etc.) and so an internal (person) attribution

becomes much more

accessible.

Taylor

and Fiske (1975) tested this

hypothesis by varying the seats of 6

people who observed 2

actors

engaged

in carefully arranged 5-minute

conversation. Observers were seated so

that faced actor A, B

or

both. Then they were asked

whom they thought had the

most impact on the

conversation.

Results:

whichever actor they faced was

perceived as the most

important of the dyad.

Cultural

differences

�

The

fundamental attribution error is more

common in individualist cultures than

collectivist (Miller,

1984)

suggesting that social learning may

also contribute to the explanation of the

effect.

�

People

in non-Western cultures are more likely to

take situational and contextual

information into

account

�

However,

cultures do not create people

with rigidly independent or

collectivistic styles, situational

factors

can trigger spontaneous self

concepts

B.

The actor-observer

bias

�

People

tend to attribute their own

behaviour to external causes

but that of others to

internal

�

Actors

overestimate

the importance of the situation in

explaining their own

behaviours: actors

look

at

the situation, observers look at

actors.

�

This

bias suggests that observers

overestimate

the importance of an actor's dispositions

for causing

the

actor's behavior;

�

Access

to different information: actors have

more background about

themselves

�

Actors

overestimate

the importance of the situation in

explaining their own

behaviors Perceptual:

actors

look at the situation, observers

look at actors

Storms's

Stusy (1973)

ν

2

participants as observers, 2 as

`conversational' actors

ν

Observers

focus attention only on the actor they

were facing

ν

Observers

emphasized dispositional factors when

explaining actor's

behaviour

ν

Actors

emphasized situational factors when

explaining their own

behaviour

Perceptual

salience: Actors attention is away

from them (external), observers

attention is on actor

(internal)

ν

The

actor-observer bias is reversed when

participants shown videotapes of their

opposite perspective

before

making attributions

Actors

saw own faces and

made an internal attribution

C.

False Consensus Effect

The

attributers draw less

dispositional inferences about

their own behaviour than

about another

person's

behaviour, because their own

behaviours is less visually

salient and because they

believe that

their

own choices are more

prevalent than they are, or

at least more prevalent than

they are viewed by

other

people who choose

differently. False consensus occurs

because our own behaviours

are relatively

easy

to imagine, because we usually

interact with "our own

kind," and because it makes us

feel good

about

ourselves.

71

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Why

do we tend to see our own

behaviour and opinions as

typical?

�

We

have a biased sample of similar

others among our

friends

�

Our

own opinions are more

accessible/ salient

�

We

fail to realize that our

choices reflect our construal

and that others have

different perceptions

�

We

are motivated to see ourselves as

normal & good.

D.

The Self-Serving Attribution

Bias (SSAB)

We

are not coldly rational

informational processors of information.

When our performance results

in

either

success or failure, we tend to

take credit for our

successes but deny blame for

our failures. Self-

serving

biases include attributing

our own (but not

other people's) successes to

internal-stable

factors

and our own (but

not other people's) failures

to external-unstable factors, taking

more

credit

than is due for desirable

outcomes, and unrealistic

(but useful) optimism about

our life

prospects.

Where we will assign the locus of

causality?: IQ, effort vs.

unreasonable professor or luck?

According

to Olson & Ross (1988), we make

internal attributions for

our successes (e.g., I'm

intelligent)

and external attributions for

failures (e.g., it was a particularly

hard exam)

Explanations

of the SSAB

ν

Motivational

Internally

attributing success and externally

attributing failure protects

self-esteem

ν

Cognitive

We

expect to do well in most things,

which make it logical to attribute

failure to external sources

(Taylor

& Riess, 1989).

E.

The ultimate attribution

error

We

attribute our group's

successes to internal factors and

other group's successes to

external factors

(Hewstone,

1990)

Accuracy

of judgments -- Our judgments are both accurate and

inaccurate.

�

We

tend to be accurate about external

visible attributes.

�

We

are less accurate about inferred internal

states (traits or

feelings).

Implications

The

process and biases of causal attribution

have important consequences

for deciding what

caused

our own and other

people's success and failure

and for attributing

responsibility or blame.

When

making attributions for

success and failure, people

who attribute their own

success to internal

causes

and their own failure to

external causes do more for

their self-esteem than do people

who make

the

opposite attributions. People

who attribute their own

success to stable causes and

their own

failure

to unstable causes have more

optimistic expectations for

the future than do people

who make

the

opposite attributions. Also,

people who attribute another

person's suffering to

uncontrollable

causes

have more pity, less

anger, and less urge to

help than do people who

attribute another person's

suffering

to controllable causes.

Attributions

of responsibility influence how

people react to personal and

social problems.

Dispositional

attributions often elicit

more punitive reactions than

do situational attributions

for

disaster

victims, quarrelling spouses,

drivers in automobile accidents,

and for people with

liver disease

and

other health problems.

Prospective jurors also make

different attributions and

award different

sentences

for rape depending on

characteristics of the victim.

Finally, attributions for

murder differ

depending

on characteristics of the victim

that the killer did

not know and depending on

the culture.

People

from collectivist cultures are

less biased toward

dispositional attributions for

murder than are

people

from individualist

cultures.

Reading

1.

Franzoi, S. (2003). Social

Psychology. Boston:

McGraw-Hill. Chapter 4.

2.

Lord, C.G. (1997). Social

Psychology. Orlando:

Harcourt Brace and Company. Chapter

4.

72

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Readings, Main Elements of Definitions

- INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Social Psychology and Sociology

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Scientific Method

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Evaluate Ethics

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY RESEARCH PROCESS, DESIGNS AND METHODS (CONTINUED)

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY OBSERVATIONAL METHOD

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY CORRELATIONAL METHOD:

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY EXPERIMENTAL METHOD

- THE SELF:Meta Analysis, THE INTERNET, BRAIN-IMAGING TECHNIQUES

- THE SELF (CONTINUED):Development of Self awareness, SELF REGULATION

- THE SELF (CONTINUE…….):Journal Activity, POSSIBLE HISTORICAL EFFECTS

- THE SELF (CONTINUE……….):SELF-SCHEMAS, SELF-COMPLEXITY

- PERSON PERCEPTION:Impression Formation, Facial Expressions

- PERSON PERCEPTION (CONTINUE…..):GENDER SOCIALIZATION, Integrating Impressions

- PERSON PERCEPTION: WHEN PERSON PERCEPTION IS MOST CHALLENGING

- ATTRIBUTION:The locus of causality, Stability & Controllability

- ATTRIBUTION ERRORS:Biases in Attribution, Cultural differences

- SOCIAL COGNITION:We are categorizing creatures, Developing Schemas

- SOCIAL COGNITION (CONTINUE…….):Counterfactual Thinking, Confirmation bias

- ATTITUDES:Affective component, Behavioral component, Cognitive component

- ATTITUDE FORMATION:Classical conditioning, Subliminal conditioning

- ATTITUDE AND BEHAVIOR:Theory of planned behavior, Attitude strength

- ATTITUDE CHANGE:Factors affecting dissonance, Likeability

- ATTITUDE CHANGE (CONTINUE……….):Attitudinal Inoculation, Audience Variables

- PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION:Activity on Cognitive Dissonance, Categorization

- PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION (CONTINUE……….):Religion, Stereotype threat

- REDUCING PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION:The contact hypothesis

- INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION:Reasons for affiliation, Theory of Social exchange

- INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION (CONTINUE……..):Physical attractiveness

- INTIMATE RELATIONSHIPS:Applied Social Psychology Lab

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE:Attachment styles & Friendship, SOCIAL INTERACTIONS

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE (CONTINE………):Normative influence, Informational influence

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE (CONTINUE……):Crimes of Obedience, Predictions

- AGGRESSION:Identifying Aggression, Instrumental aggression

- AGGRESSION (CONTINUE……):The Cognitive-Neo-associationist Model

- REDUCING AGGRESSION:Punishment, Incompatible response strategy

- PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR:Types of Helping, Reciprocal helping, Norm of responsibility

- PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE………):Bystander Intervention, Diffusion of responsibility

- GROUP BEHAVIOR:Applied Social Psychology Lab, Basic Features of Groups

- GROUP BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE…………):Social Loafing, Deindividuation

- up Decision GROUP BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE……….):GroProcess, Group Polarization

- INTERPERSONAL POWER: LEADERSHIP, The Situational Perspective, Information power

- SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN COURT

- SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN CLINIC

- FINAL REVIEW:Social Psychology and related fields, History, Social cognition