|

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Lesson

15

PERSON

PERCEPTION: WHEN PERSON PERCEPTION IS

MOST CHALLENGING

Aims:

�

Evaluating

when person perception can

be most challenging

Objectives:

�

Discussing

how perception of baby or mature

aces affects people's perceptions.

�

Describing

how to detect lies.

Link

to previous two lectures on

person perception

When

we perceive other people, we

start with salient

categories such as sex, race, or

age. We

use

the category to make initial

assumptions about the

person. If we are willing and

able to do so, we

also

gather additional verbal or

nonverbal information. We often

interpret the new

information as

consistent

with our first impression.

If the new information seems

inconsistent enough, we

sometimes

re-categorize

the person or come to regard

the person as an individual. Person

perception, however, is

slanted

toward perceiving people as

merely instances of a category rather

than as individuals.

Additional

verbal information can sometimes

undo category-based assumptions,

but only when

the

perceiver

is highly motivated to form an

individual impression. Some types of

verbal information, such

as

knowing how the individual

behaves, are as likely as physically

salient categories to

generate

spontaneous

trait inferences. Nonverbal

information also offers many

cues to forming an

impression.

We

draw different inferences

about people depending on

how dominant and attractive

their face

appears,

how high-pitched their

voices seem, how youthfully

they walk, and how

often and youthfully

they

walk, and how often

and intimately they touch

each other.

"Accuracy"

in person perception can be defined as

agreement between the

perceiver and the

target

of

perception, agreement between

two or more perceivers, or

whether the perceiver's

impression predicts

the

target person's future behavior. By

any measure, perceivers are

more likely to be accurate

about

evolutionarily

significant traits than

about other traits. Contrary

to popular belief, accuracy does

not

improve

with length of

acquaintance.

Person

perception from verbal

information is subject to several biases.

When perceivers learn

about

a target person's traits in a specific

order, for example, the

initial traits affect the

final impression

more

than do subsequent traits.

Initial traits also change

the meaning of subsequent traits,

because

perceivers

use several effective strategies to

interpret seemingly inconsistent

information in a way

that

"fits"

the initial impression.

Perceivers are also biased

by implicit personality theories.

They believe that

knowing

one fact about a person,

especially the person's standing on a

"central trait," allows

confident

inferences

about many other facets of

the person's character.

Perceiving

people's emotions from nonverbal

information is also difficult.

Despite some

universals

in how people display their

emotions, different cultures

have different "display

rules."

Knowledge

of local display rules is

necessary for successful

"decoding" of a target person's

emotions.

Also,

people are good at faking

facial expressions and other

nonverbal cues when they

want to mislead

perceivers.

Women are better than men at

"reading" the valid cues to

emotion.

When

is person perception most

challenging?

Person

Perception is the foundation of all

social interactions: work,

politics, patient-doctor

relationship,

romantic

attachments, legal decisions, and

international diplomacy. Usually it

works well, but

sometimes

person

perception gets very tricky

and challenging. Although there could be

several instances where person

perception

can be demanding, there are

particularly two instances where it

could be very

challenging:

1.

Perceiving

baby faces

2.

Detecting

lies

61

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

Perceiving

baby faces

It

becomes very difficult to be

objective in case of very

attractive characteristics of people

with

whom

we interact. Similarly for

certain people, we feel more sympathetic

for example we feel

sympathy

toward

handicapped. The perception of baby faced

people is most tricky. We

tend to treat baby faced as

babies,

which are considered dependent and

fragile. Young of many

species can look after

themselves after

weeks

of their birth, but a human

child is dependent for years.

Human beings are prepared by

their

Evolutionary

history to treat baby-faced in the same

way as they do with

children. Baby faced

are

unanimously

explained as having large

eyes, a small chin, thin

eyebrows, and a small nose.

Stability

of facial features

Zebrowitz

and Montepare (1992) found

that the adult's perceivers agreed almost

perfectly on which were

the

baby-faced persons and which were the

more mature-faced persons when they

saw photographs of 6

age

groups: infants, preschoolers, fifth

graders, eighth graders,

young adults, and older adults.

People

who have baby faces also

tend to keep their immature

facial features as they move

from one age

group

to the next. Zebrowitz et al.

(1993) showed that the

perception about someone

having a baby or

mature

face was stable over the

years. However, women were

less likely to retain their

baby faces from

high

school to their thirties. For

both sexes, having a bay

face at age 30 did not

predict having a baby

face

at

age 50 though.

Baby

faced people may also come

to believe they have the traits

others assume they have

(self-fulfilling

prophecy).

Consistent with this, in one

study the researchers Berry &

Brownlow's (1989) found that

baby-

faced

women perceived themselves as

less likely to carry tasks

requiring strength. Baby faced are

also

perceived

as having some positive

traits, e.g., warmth, trustworthy,

etc., and this perception is

remarkably

stable

across cultures. One study

showed that baby faced were

perceived as weak, na�ve,

but

interpersonally

warm, honest, & dependent by

Americans (white, black) and

Korean students (Zebrowitz

et

al.,

1993)

Positive

and negative

consequences

There

are many positive and

negative consequences of perceiving

baby faced people as this

perception will

affect

every field of life: media,

work, legal system, and

interpersonal attractions.

Interpersonal

interactions:

It

has been found that

people behave and speak to baby-faced

differently. As people think

that children at

younger

ages require different treatment

because of their cognitive

immaturity, they may deal

baby-faced in

the

same way, like speaking

slowly and clearly. In one study,

student's teachers taught two

complicated

tasks

to a preschooler. Some students were shown pictures of

baby-faced preschoolers while

others saw

those

of more mature faces. The telephonic

conversation was recorded so that the

experimenter could

determine

to what extent the student teachers

clarified, simplified, tried to get

and hold attention, and

spoke

slowly.

The results showed that the

adult teachers were more apt to use

baby talk when talking to

the baby

faced.

(Zebrowitz et al.,

1992)

Perception

about traits:

Adults

may assume that baby-faced

are more honest but less

intellectually competent. In one

study

(Brownlow

& Zebrowitz, 1990), videotapes of 150

TV commercials were taken from morning,

afternoon

and

evening time slots, and it

was found that the

baby-faced were cast primarily in

commercials

emphasizing

trust, while mature-faced were shown in commercials emphasizing

expertise

Problems

in jobs:

Another

important consequence of having a

baby face occurs when

people apply for jobs.

Baby-faced

applicants

may be at a disadvantage compared to

their mature-faced peers when

they apply for certain

types

62

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

of

jobs, most notably higher-status

jobs that require leadership. In a

study of how facial features

might

influence

occupational hiring, college

students examined resumes

that included demographic and

academic

details.

The examiners attached to each

resume a photograph of a person

who had either a baby

face or

mature

face. Both faces were

equally attractive. The

students made hiring decisions

about two jobs at a

children's

day care centre: teacher and

director. The results showed

that the baby-faced were selected

more

frequently

for teaching job, while the

mature-faced were considered appropriate for the

post of director

(Zebrowitz

et al., 1991). Moreover,

women applicants were more likely to be

hiding for teacher job

and

men

for director jobs. These

findings indicate that the

decision was only based on

face, not on the

resume.

These

results clearly demonstrate

that baby-faced individuals

may be discriminated against in ways that

are

legally

prohibited for race and

sex.

Double

standard of justice:

Research

has shown that baby-faced

are convicted less for

causing intentional harm, but are

accused more

for

causing negligent harm (Zebrowitz &

McDonald, 1991)

Facial

maturity and jury

decisions

To

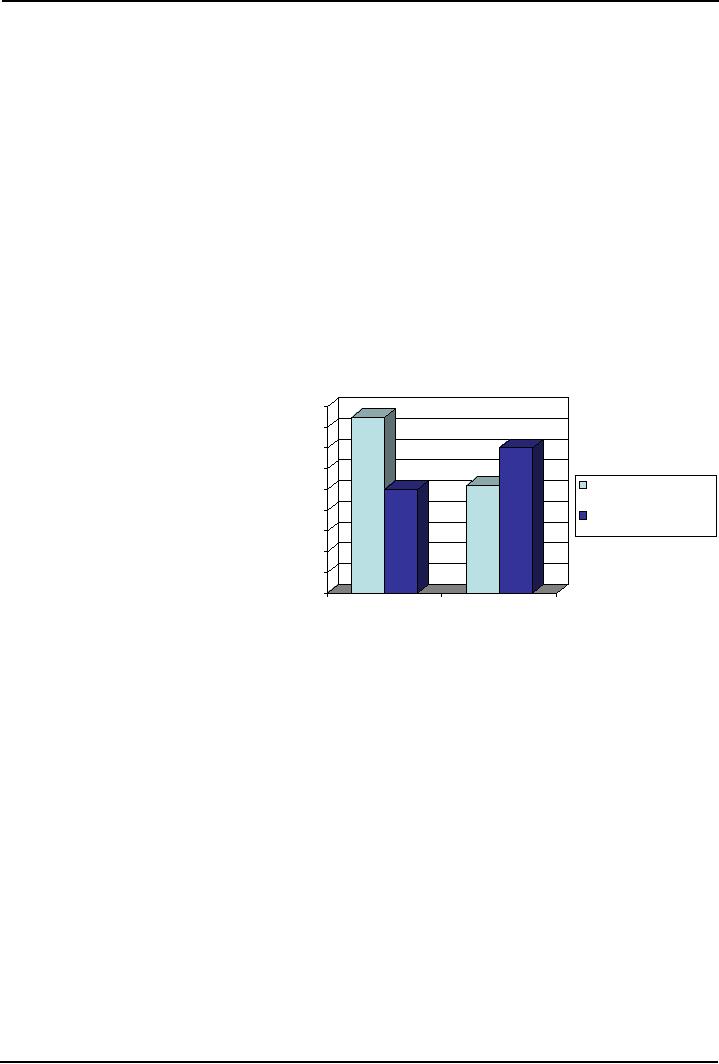

summarize, baby faced

are

perceived

differently which

affect

Berry

et al., 1988

many

kinds of

interpersonal

interactions.

Because babies need

0.9

protection,

perceivers assume

that

adults

who have baby faces

also

0.8

have

childlike traits. Baby faces

are

0.7

easy

to identify across cultures

and

0.6

across

the life span. People

who

Mature

faced

0.5

defendant

have

baby faces are treated

as

0.4

Baby

faced defendant

though

they are warm

and

0.3

approachable,

but also as though

0.2

they

are weak and

incompetent.

0.1

Perceivers

trust baby faced actors

in

0

television

commercials to be honest,

Intentional

crime

Negligent

crime

hire

baby-faced applicants for

jobs

that

require interpersonal warmth,

and treat baby-faced

defendants leniently when

they are charged

with

causing intentional harm.

Conversely, perceivers "talk down" to

baby faced pupils, avoid

choosing

baby

faced workers for leadership

positions, and consider baby

faced defendants likely to

have caused

negligent

harm.

Detecting

Lies

The

success or failure of business

deals, romantic relationships,

international trade, murder trials,

depend

importantly

on whether perceivers believe that

another person is telling the truth. Of

all organisms,

however,

the most skillful deceiver is the human

being who is the acknowledged

master of deceit and

speaks

lies in love and war

and who indulges himself in

little white lies. People

lie because it is adaptive

to

do

so, and because people get

benefit from it.

Why

lying is successful?

�

Perceivers

have a truthfulness bias (Zuckerman et

al., 1981).

�

Most

behaviour is accepted uncritically at

face value

�

To

doubt a target person's authority often

runs the risk of hurting the

perceiver's own

feelings

Accuracy

in judgment

�

People,

who have access to multiple

channels of communication, tend to be

more accurate in

judging

others' emotions.

63

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

�

Nonverbal

leakage: True

emotions tend to "leak" out

through nonverbal

channels

�

The

body is more likely than the

face to reveal

deception

�

Generally,

the verbal channel tends to be the most

influential.

�

Lying:

The Giveaways

Liars

blink more, hesitate more, make more

speech errors, speak in higher-pitched

voices, and have

more

dilated pupils

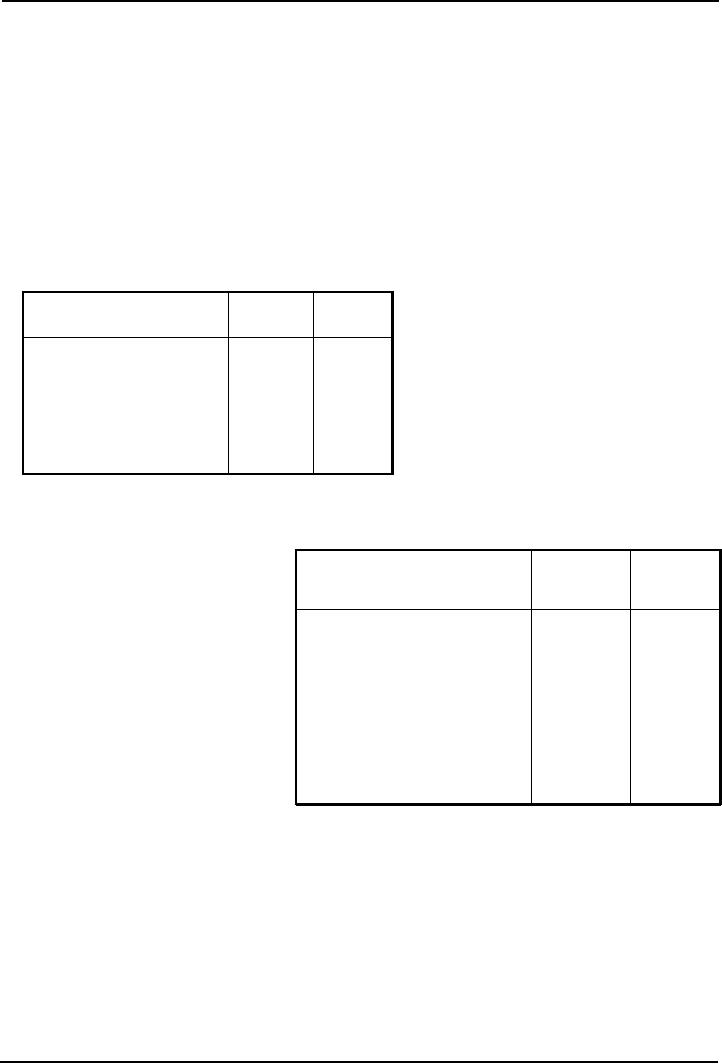

Tables

1-4 displayed below describe

how different forms of clues

can be employed to detect

lies:

T

a b le 1 :C u e s to d e c e p tio n : V e rb a l c u e

s

P

e rce iv e rs

Is

it a v a lid

V

e rb a l c u e s

lo

o k fo r it

cue?

Yes

No

N

e g a tiv e s ta tem e n ts

Yes

No

Irre

le v a n t s ta tem e n ts

Yes

No

G

e n e ra lizin g

Yes

No

D

istancin g

T

a b le 2 : C u e s to d e c e p tio n : V o ca l c u e

s

Perceivers

Is

it a valid

Vocal

cues

look

for it

cue?

Hesitation

Yes

Yes

Yes

Higher

pitch

Yes

Yes

Speech

errors

Yes

Delay

before speaking

Yes

Yes

Yes

Speaking

slowly

Yes

Length

of speaking

Yes

Yes

64

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

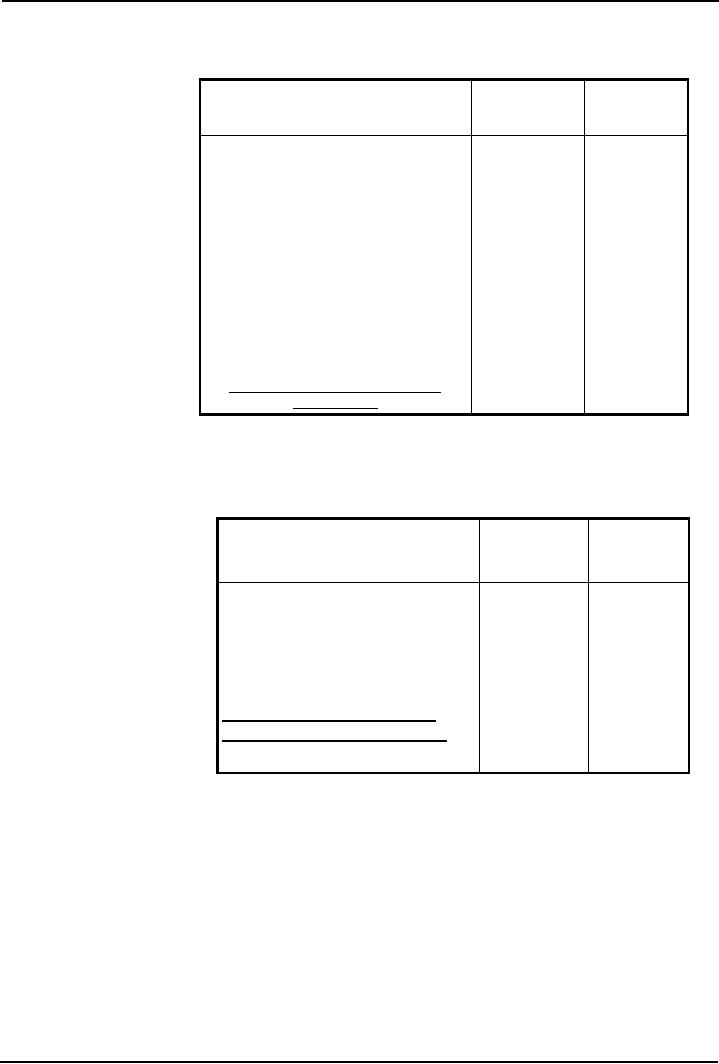

Table

3. Cues to deception: Visual

Cues

Perceivers

Is

it a valid

Visual

cues

look

for it

cue?

Yes

No

�Dialated

pupils

Yes

No

�Adaptor

behaviour

Yes

No

�Blinks

Yes

No

�Shrugs

No

Yes

�Avoiding

eye contact

No

Yes

�Posture

shifts

Yes

Yes

�Not

smiling

Yes

No

�Emblems

(Prof. accused)

Yes

No

�Illustrators

No

Yes

�Manipulators

(People

rely usually on wrong

ones

Ekman,

1985)

Table

4: Cues to deception:

Miscellaneous

cues

Perceivers

Is

it a valid

Miscellaneous

cues

look

for it

cue?

Discrepancies

No

Yes

Planning

time

No

Yes

Seem

rehearsed

No

Yes

Guilt,

heightened emotions:

blinking,

shrugging, sweating

Applied

Social Psychology

Lab

�

"Always

tell the truth. Then you

don't have to remember anything"

(Mark Twain,

1835-1910)

�

Paula

DePaula's lying figures (1996): In a

week a person speaks 10 lies

on average; people lie to

one

thirds of people they

interact

�

People

who are more sociable, manipulative, and

concerned about creating

favourable self-

impression

are more likely to

lie.

�

Analyze

yourself that when you

lie, how do you conceal

it, and what cues

you use when you

lie in

your

everyday life.

65

Social

Psychology (PSY403)

VU

How

to detect lie?

�

One

study found that inaccurate judges

(30% accuracy or worse) focused on

verbal cues, compared

to

accurate judges (80% or more) who

focused on nonverbal cues

(Ekman & Sullivan,

1991)

�

We

are easily deceived when we

are involved in

discussion

�

In

nonverbal cues, biggest mistake is

placing too much emphasis on

the face (Ekman et al.,

1988)

like

on baby or attractive

faces.

�

In

one study a sample of female

nurses watched disgusting or pleasant

short films and they were

instructed

to either report their

honest feelings about the

film or to conceal their

feelings. Hidden

video

cameras either focused on

their faces or their

body/behaviour. These tapes were

later viewed

by

some judges. The results

showed that the judges who were

focusing on body movement

like

fidgeting

fingers, shifts of body,

etc. were more successful in detecting

lies of nurses (Ekman

&

Friesen,

1974).

It

can be concluded that people

lie because they benefit

from doing so. Ironically,

the more liars have

to

gain

from lying, the easier they

are to detect. Lie detection,

however, is far from accurate.

Perceivers

rely

on cues that are not

helpful and ignore cues

that would be helpful. One

frequently used cue is an

"honest

face." Another is expectancy

violation. Because expectancies differ

from one culture to the

next,

lie

detection across cultures is

very difficult. Within a

culture, some people are

better than others at

telling

and detecting lies.

Readings

1.

Franzoi,

S.L. (2006). Social

Psychology. New

York: McGraw Hill. Chapter

4.

2.

Lord,

C.G. (1997). Social

Psychology. Orlando:

Harcourt Brace and Company. Chapter

3.

66

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Readings, Main Elements of Definitions

- INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Social Psychology and Sociology

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Scientific Method

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY:Evaluate Ethics

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY RESEARCH PROCESS, DESIGNS AND METHODS (CONTINUED)

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY OBSERVATIONAL METHOD

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY CORRELATIONAL METHOD:

- CONDUCTING RESEARCH IN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY EXPERIMENTAL METHOD

- THE SELF:Meta Analysis, THE INTERNET, BRAIN-IMAGING TECHNIQUES

- THE SELF (CONTINUED):Development of Self awareness, SELF REGULATION

- THE SELF (CONTINUE…….):Journal Activity, POSSIBLE HISTORICAL EFFECTS

- THE SELF (CONTINUE……….):SELF-SCHEMAS, SELF-COMPLEXITY

- PERSON PERCEPTION:Impression Formation, Facial Expressions

- PERSON PERCEPTION (CONTINUE…..):GENDER SOCIALIZATION, Integrating Impressions

- PERSON PERCEPTION: WHEN PERSON PERCEPTION IS MOST CHALLENGING

- ATTRIBUTION:The locus of causality, Stability & Controllability

- ATTRIBUTION ERRORS:Biases in Attribution, Cultural differences

- SOCIAL COGNITION:We are categorizing creatures, Developing Schemas

- SOCIAL COGNITION (CONTINUE…….):Counterfactual Thinking, Confirmation bias

- ATTITUDES:Affective component, Behavioral component, Cognitive component

- ATTITUDE FORMATION:Classical conditioning, Subliminal conditioning

- ATTITUDE AND BEHAVIOR:Theory of planned behavior, Attitude strength

- ATTITUDE CHANGE:Factors affecting dissonance, Likeability

- ATTITUDE CHANGE (CONTINUE……….):Attitudinal Inoculation, Audience Variables

- PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION:Activity on Cognitive Dissonance, Categorization

- PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION (CONTINUE……….):Religion, Stereotype threat

- REDUCING PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION:The contact hypothesis

- INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION:Reasons for affiliation, Theory of Social exchange

- INTERPERSONAL ATTRACTION (CONTINUE……..):Physical attractiveness

- INTIMATE RELATIONSHIPS:Applied Social Psychology Lab

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE:Attachment styles & Friendship, SOCIAL INTERACTIONS

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE (CONTINE………):Normative influence, Informational influence

- SOCIAL INFLUENCE (CONTINUE……):Crimes of Obedience, Predictions

- AGGRESSION:Identifying Aggression, Instrumental aggression

- AGGRESSION (CONTINUE……):The Cognitive-Neo-associationist Model

- REDUCING AGGRESSION:Punishment, Incompatible response strategy

- PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR:Types of Helping, Reciprocal helping, Norm of responsibility

- PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE………):Bystander Intervention, Diffusion of responsibility

- GROUP BEHAVIOR:Applied Social Psychology Lab, Basic Features of Groups

- GROUP BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE…………):Social Loafing, Deindividuation

- up Decision GROUP BEHAVIOR (CONTINUE……….):GroProcess, Group Polarization

- INTERPERSONAL POWER: LEADERSHIP, The Situational Perspective, Information power

- SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN COURT

- SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED: SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY IN CLINIC

- FINAL REVIEW:Social Psychology and related fields, History, Social cognition