|

Organizational

Psychology (PSY510)

VU

LESSON

04

DEFINING

THE CULTURE

Culture

may be understood as:

�

the

set of common understandings expressed in

language

�

values,

beliefs and expectations

that members come to

share

�

a

system for creating,

sending, storing and processing

information

�

the

collective of the mind which

distinguishes the members of one

group of people from another

The

world culture has been derived

from the Latin word cultura

stemming

from colere, meaning

"to cultivate".

It

generally refers to patterns of

human activity and the

symbolic structures that give

such activity

significance.

Different definitions of "culture"

reflect different theoretical bases for

understanding, or

criteria

for evaluating, human

activity.

Anthropologists

most commonly use the term "culture" to

refer to the universal human capacity to

classify

codify

and communicate their

experiences symbolically. This capacity

has long been taken as a

defining

feature

of the humans. Many observers

have shown that there

are cultural differences

in:

o

Self

perception

Self

perception is how people belonging to different

culture look at themselves. For

example,

in

some cultures people are

viewed as honest while in

other people are cynical about

each

other.

Therefore, they act accordingly taking or

not taking precautionary

measures.

o

Relationship

with world

This

refers to the inclination of the people to dominate

their environment to,

perhaps extract

the

most out of it. Further, it

also refers to the acceptability of

other cultures. In simpler

terms,

relationship

with the world refers to the

terms that people have with

their environment and

the

rest

of the world.

o

Time

Dimension

Time

dimension refers to the past, present or

future orientation of the people in a culture.

It

means

that people in a particular culture may either be

concerned about their future or

present

or

past. The Japanese culture is a

future oriented while the American

culture is considered to be

a

present oriented.

o

Public

and private space

In

some cultures, people prefer to be

sitting alone in their

cabins at their workplace,

while in

other

cultures, people tend to inclined

towards common working space

where they sit together

and

work. Therefore, the public or private

space orientation is also a

differentiating feature of

cultures.

Key

Components of Culture

A

common way of understanding culture sees it as

consisting of four elements

that are "passed on

from

generation

to generation by learning alone":

1.

Values

2.

Norms

3.

Institutions

4.

Artifacts

Values

comprise ideas about what in

life seems important. They

guide the rest of the culture. Norms

consist

of

expectations of how people will

behave in various situations.

Each culture has methods,

called sanctions,

of

enforcing its norms.

Sanctions vary with the importance of the

norm; norms that a society

enforces

formally

have the status of laws.

Institutions are the structures of a

society within which values

and norms

are

transmitted. Artifacts are things, or

aspects of material culture.

Organizational

Culture

Just

as a country has a culture, organizations

also have culture which is influenced by

the national culture.

With

respect to cultural differences affecting

organizational psychology, two major researches

need to be

quoted:

�

Geert

Hofstede's research; and

�

Trompenaar's

Research

10

Organizational

Psychology (PSY510)

VU

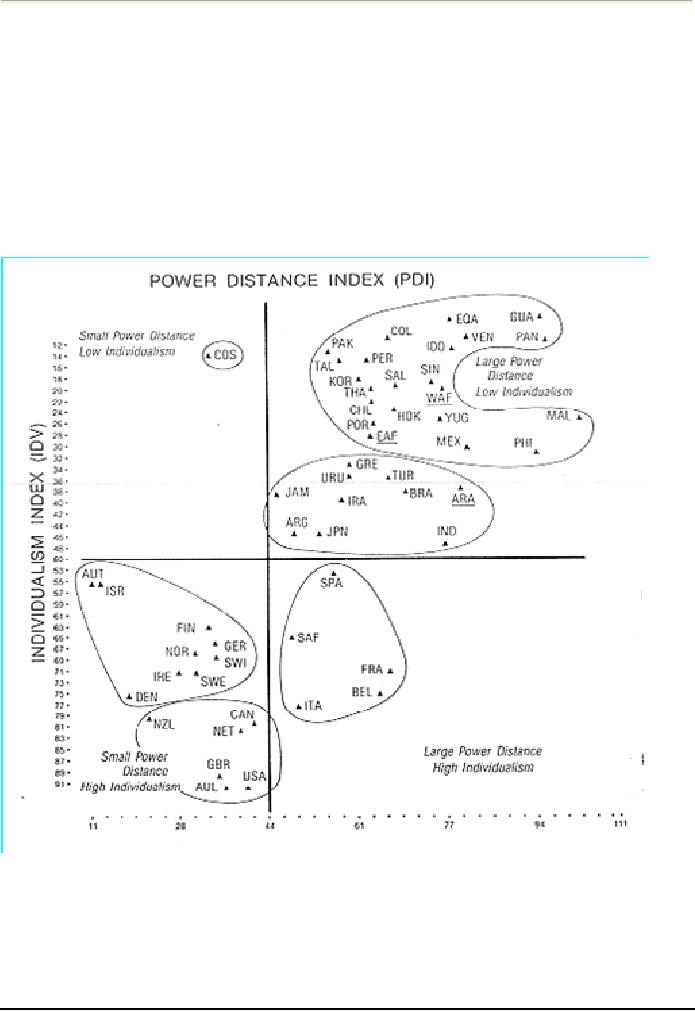

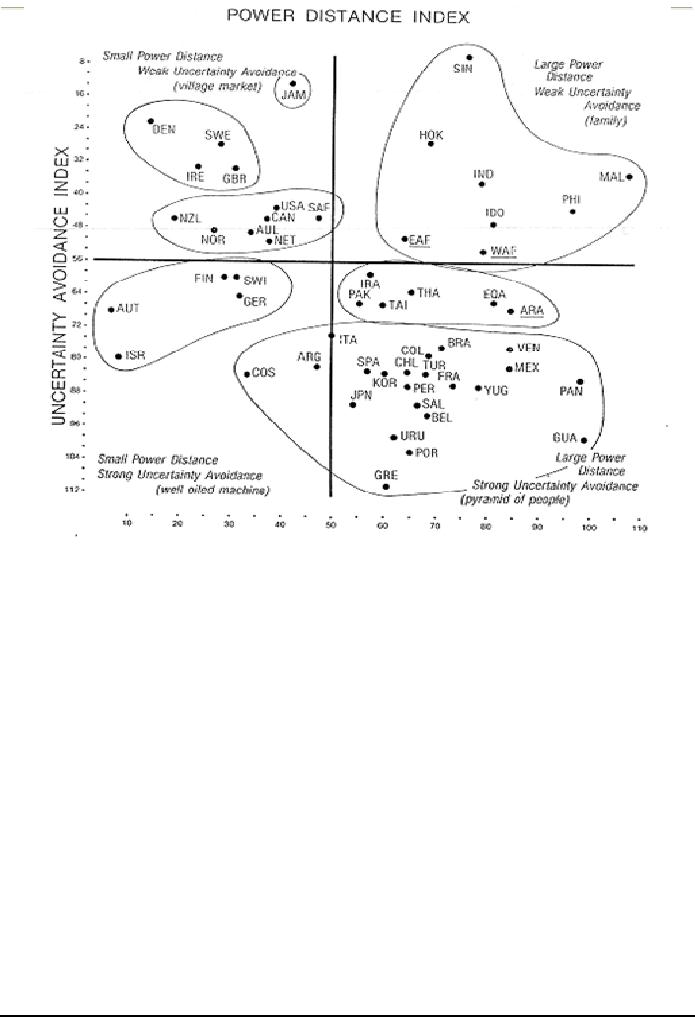

Geert

Hofstede's Research

Hofstede

researched on 116,000 workers of IBM

spread over 70 countries

world wide. He discovered

that

organizational

culture differs in the following four

terms:

�

Power

distance (acceptance of other's

power)

�

Masculinity/Femininity

�

Indvidualism/collectivism

�

Uncertainty

avoidance

Power

Distance Index (PDI) that

is the extent to which the less powerful

members of organizations

and

institutions

(like the family) accept and

expect that power is distributed

unequally. This represents

inequality

(more

versus less), but defined

from below, not from

above. It suggests that a

society's level of inequality is

endorsed

by the followers as much as by the

leaders. Power and

inequality, of course, are

extremely

fundamental

facts of any society and

anybody with some international

experience will be aware

that 'all

societies

are unequal, but some

are more unequal than

others'.

Individualism

(IDV) on the

one side versus its

opposite, collectivism, that is the degree to

which

individuals

are integrated into groups. On the

individualist side we find

societies in which the ties

between

individuals

are loose: everyone is

expected to look after him/herself

and his/her immediate

family. On the

collectivist

side, we find societies in

which people from birth

onwards are integrated into

strong, cohesive

in-groups,

often extended families

(with uncles, aunts and

grandparents) which continue

protecting them in

exchange

for unquestioning loyalty. The

word 'collectivism' in this sense has no

political meaning: it

refers

to

the group, not to the state. Again, the

issue addressed by this dimension is an

extremely fundamental one,

regarding

all societies in the

world.

11

Organizational

Psychology (PSY510)

VU

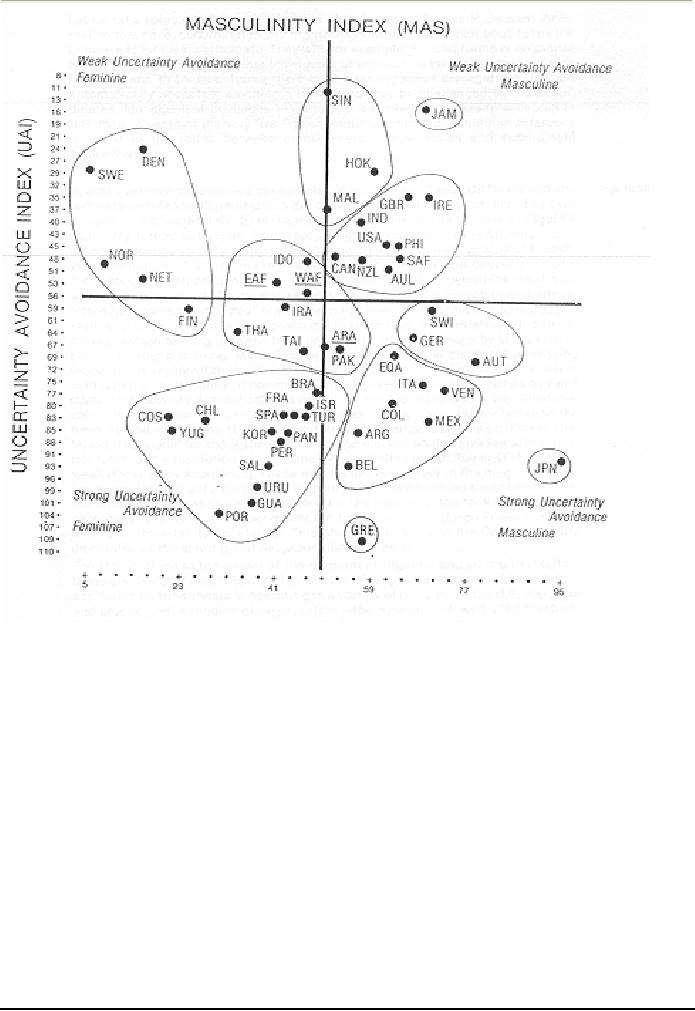

Masculinity

(MAS) versus

its opposite, femininity refers to the

distribution of roles between the

genders

which

is another fundamental issue for any

society to which a range of solutions

are found. The IBM

studies

revealed that (a) women's

values differ less among

societies than men's values; (b)

men's values from

one

country to another contain a dimension from very

assertive and competitive

and maximally different

from

women's values on the one

side, to modest and caring

and similar to women's

values on the other.

The

assertive pole has been

called 'masculine' and the

modest, caring pole 'feminine'.

The women in

feminine

countries have the same

modest, caring values as the

men; in the masculine countries they

are

somewhat

assertive and competitive, but

not as much as the men, so

that these countries show a

gap

between

men's values and women's

values. The following table

shows some of the basic

characteristics of

Feminine

and Masculine societies.

Feminine

societies

Masculine

societies

Assertiveness

ridiculed

Assertiveness

appreciated

Undersell

yourself

Oversell

yourself

Stress

on life quality

Stress

on careers

Intuition

Decisiveness

12

Organizational

Psychology (PSY510)

VU

Uncertainty

Avoidance Index (UAI) deals

with a society's tolerance

for uncertainty and ambiguity; it

ultimately

refers to man's search for

Truth. It indicates to what extent a culture

programs its members

to

feel

either uncomfortable or comfortable in unstructured

situations. Unstructured situations are

novel,

unknown,

surprising, and different

from usual. Uncertainty

avoiding cultures try to minimize the

possibility

of

such situations by strict laws

and rules, safety and

security measures, and on the

philosophical and

religious

level by a belief in absolute Truth;

'there can only be one

Truth and we have it'.

People in

uncertainty

avoiding countries are also

more emotional, and motivated by

inner nervous energy.

The

opposite

type, uncertainty accepting cultures, are

more tolerant of opinions

different from what they

are

used

to; they try to have as few

rules as possible, and on the

philosophical and religious level they

are

relativist

and allow many currents to

flow side by side. People

within these cultures are

more phlegmatic and

contemplative,

and not expected by their

environment to express

emotions.

13

Organizational

Psychology (PSY510)

VU

Long-Term

Orientation (LTO) versus

short-term orientation: this fifth dimension

was found

in

a study among students in 23

countries around the world, using a

questionnaire designed by

Chinese

scholars It can be said to

deal with Virtue regardless

of Truth. Values associated

with

Long

Term Orientation are thrift

and perseverance; values

associated with Short

Term

Orientation

are respect for tradition,

fulfilling social obligations, and

protecting one's 'face'.

Both

the

positively and the negatively rated

values of this dimension are found in the

teachings of

Confucius,

the most influential Chinese

philosopher who lived around

500 B.C.; however, the

dimension

also applies to countries

without a Confucian heritage.

14

Organizational

Psychology (PSY510)

VU

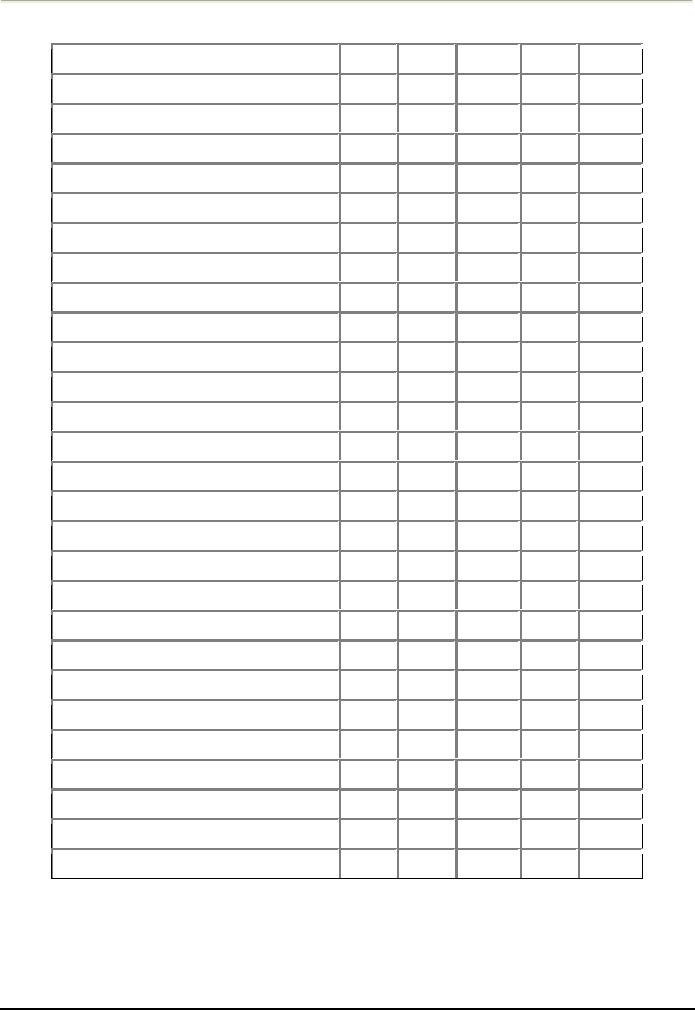

The

following table shows the

ratings for some countries

of the world on Hofstede's

dimensions:

Country

PDI

IDV

MAS

UAI

LTO

Arab

World

80

38

52

68

Australia

36

90

61

51

31

Canada

39

80

52

48

23

China

80

20

66

30

118

Denmark

18

74

16

23

France

68

71

43

86

Germany

35

67

66

65

31

Hong

Kong

68

25

57

29

96

India

77

48

56

40

61

Indonesia

78

14

46

48

Israel

13

54

47

81

Italy

50

76

70

75

Japan

54

46

95

92

80

Malaysia

104

26

50

36

Mexico

81

30

69

82

Netherlands

38

80

14

53

44

New

Zealand

22

79

58

49

30

Norway

31

69

8

50

20

Pakistan

55

14

50

70

0

Russia

93

39

36

95

Singapore

74

20

48

8

48

South

Korea

60

18

39

85

75

Sweden

31

71

5

29

33

Switzerland

34

68

70

58

Taiwan

58

17

45

69

87

United

Kingdom

35

89

66

35

25

United

States

40

91

62

46

29

Trompenaar's

Research

Trompenaar's

research comprised 15000

managers in 28 countries. Having

researched and

written

extensively

on how reconciling cultural differences

can lead to competitive

advantage, Fons Trompenaars

is

now

widely recognised as a leading

authority on organisational culture.

To

Fons Trompenaars, knowledge management

is, or should be, fundamentally a cultural

issue. "Data

becomes

meaningful when you structure it in a

certain way it becomes

information. When you

structure

15

Organizational

Psychology (PSY510)

VU

information,

it becomes knowledge, and when you

structure knowledge it becomes science,

it is the process

of

structuring that adds meaning.

And since different cultures

have different ways of structuring

meaning,

you

can see that, by definition, knowledge

management is a cultural construct."

He

identified the following dimensions of

culture:

o

Universalism/Particularism

practices applied universally and in particular

countries

o

Individualism/collectivism

o

Neutral/Affective:

emotions held in control; affective

cultures emotions are openly

expressed.

o

Specific/diffuse:

differences in public/private space

sharing.

o

Achievement/Ascription:

stress of a person on his

work/achievement, or stress on who

a

person

is

The

first of these he identifies as the

universal versus the particular, a

dilemma that he explores in

great

depth

in his book, Did the

Pedestrian Die? "Imagine you're going in

a car, you're friend is speeding

and he

hits

a pedestrian. You come to court,

and your friend's lawyer

tells you not to worry, as

you were the only

witness.

You know he was speeding,

but what right does your

friend have to ask you to

lie? Would you do

so?"

This is a question that vividly

demonstrates the divide between

universalist and particularist

thinking.

Trompenaars's

research has revealed that

92 per cent of Americans,

for example, would fall

into the

universalist

camp: respect to the truth

and to the law overrides any

notion of there being exceptions to

the

rule.

Conversely, the majority of those in

South Korea, Venezuela and

France (and indeed most of

the Latin

world)

would tend to a more particularistic

standpoint: in Trompenaars's experience,

most ask for

more

information

before they are able to decide whether

they would lie for their

friend, the most common

question

being, did the pedestrian

die?

In

a corporate context, this cultural dilemma raises

obvious difficulties for a knowledge

manager,

particularly

those operating in a multinational organization.

Even on a functional level, it is a disparity

that

needs

to be addressed. As Trompenaar says,

while HR, finance and

marketing professionals are

generally

Universalist

in their outlook, salespeople tend to be

more particularist they invariably

demand exceptions

for

their clients, for example.

For a KM system to succeed, therefore, it

must reconcile the

two.

Implementing

a standardized system in every

office around the world and

across functions will

isolate the

particularist,

just as allowing every office

and department to develop their own

approach to KM will lead

to

chaos.

"Mass customization is the reconciliation of the

universal and the particular," he

says. "You will

not

solve

knowledge management through one

approach alone; it's about how

you combine the two."

The

second of Trompenaar's five dimensions is

the individual versus the team,

which is closely aligned

to

the

third: specific and codified

versus diffuse and implicit knowledge. He

himself relates "a short time ago

we

worked with General Motors to

help integrate its joint

venture with Isuzu, a Japanese

truck-producing

firm.

Because their knowledge was so

individualized, the Americans spent

about 30 per cent of their

time

codifying

their knowledge and writing it up in

handbooks and procedures. The

Japanese, on the other

hand,

never

wrote anything down. Their

knowledge was stored in the network of

their relationships. This

infuriated

the Americans, but in a group-oriented

culture, you need other ways

of communicating

knowledge.

Whereas in an individualized society,

there is a tendency to keep knowledge

because knowledge

is

seen as power, in Japan, knowledge is

only knowledge when it is shared; your

status is dependent on

how

much

you contribute to the

group."

Eventually,

GM's managers succeeded in

convincing their Japanese

counterparts to compile more

concise,

less

time-consuming manuals, which went

some way to satisfying both

parties, but the challenge

of

reconciling

the individual and the group, particularly in an

international organization, is

clear.

The

last of Trompenaars's five

dimensions of knowledge management

relates to the disparity between

perceptions

from the top down and

from the bottom up. "Data

about clients and products

is stored in the

heads

of individual staff members," he says.

"Middle management translates it

into information that in

turn

is

organized as knowledge by top management.

For effective KM, the reconciliation of this

dilemma can be

found

in `middle-up-down', in which middle

management is the bridge between the

standards of top

management

and the chaotic reality of those on the

front line," he says. It can

also be reconciled by the

`servant

leader', he continues, a leader

who connects the bottom with

the top through the style

with which

he

or she leads, drawing their

authority by serving the community as a whole. In

Trompenaars's view, this is

an

approach Goldman Sachs seems

to have mastered.

16

Organizational

Psychology (PSY510)

VU

REFERENCES

�

Trompenaars,

F., Did the Pedestrian Die?

(Capstone Publishing, 2003)

�

Trompenaars,

F. & Hampden-Turner, C., 21 Leaders

for the 21st Century (Capstone Publishing,

2001)

�

Geert-Hofstede's

research:http://www.geert-hofstede.com/geert_hofstede_resources.shtml

�

Detailed

article on defining culture:

http://courses.ed.asu.edu/margolis/spf301/definitions_of_culture.html

FURTHER

READING

�

Dictionary

of the History of Ideas: "culture"

and "civilization" in modern

times:

http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/cgi-local/DHI/dhi.cgi?id=dv1-73

�

Countries

and their Cultures:

http://www.everyculture.com/

�

Global

Culture Essays on globalization,

migration and their impact

on global culture: http://global-

culture.org/

�

What

is Culture? - Washington State

University:

http://www.wsu.edu/gened/learn-

modules/top_culture/culture-index.html

�

Define

Culture - List of definitions of culture

from people around the world:

http://www.defineculture.com/

�

Arnold,

Matthew. 1869. Culture and

Anarchy. New York:

Macmillan. Third edition,

1882, available

online.

Retrieved: 2006-06-28.

�

Forsberg,

A. Definitions of culture CCSF Cultural

Geography course notes. Retrieved:

2006-06-29.

http://fog.ccsf.cc.ca.us/~aforsber/ccsf/culture_defined.html

17

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO ORGANIZATIONAL PSYCHLOGY:Hawthorne Effect

- METHODOLOGIES OF DATA COLLECTION:Observational method, Stability of Measures

- GLOBALIZATION:Aspects of Globalization, Industrial Globalization

- DEFINING THE CULTURE:Key Components of Culture, Individualism

- WHAT IS DIVERSITY?:Recruitment and Retention, Organizational approaches

- ETHICS:Sexual Harassment, Pay and Promotion Discrimination, Employee Privacy

- NATURE OF ORGANIZATIONS:Flat Organization, Neoclassical Organization Theory

- ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE:Academy Culture, Baseball Team Culture, Fortress Culture

- CHANGING ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE:Move decisively, defuse resistance

- REWARD SYSTEMS: PAY, Methods of Pay, Individual incentive plan, New Pay Techniques

- REWARD SYSTEMS: RECOGNITION AND BENEFITS, Efficiency Wage Theory

- PERCEPTION:How They Work Together, Gestalt Laws of Grouping, Closure

- PERCEPTUAL DEFENCE:Cognitive Dissonance Theory, Stereotyping

- ATTRIBUTION:Locus of Control, Fundamental Attribution Error

- IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT:Impression Construction, Self-focused IM

- PERSONALITY:Classifying Personality Theories, Humanistic/Existential

- PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT:Standardized, Basic Categories of Measures

- ATTITUDE:Emotional, Informational, Behavioural,Positive and Negative Affectivity

- JOB SATISFACTION:The work, Pay, Measurement of Job Satisfaction

- MOTIVATION:Extrinsic motive, Theories of work motivation, Safety needs

- THEORIES OF MOTIVATION:Instrumentality, Stacy Adams’S Equity theory

- MOTIVATION ACROSS CULTURES:Meaning of Work, Role of Religion

- POSITIVE PSYCHOLOGY:Criticisms of ‘Traditional’ Psychology, Optimism

- HOPE:Personality, Our goals, Satisfaction with important domains, Negative affect

- EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE:EI IS Related To Emotions and Intelligence

- SELF EFFICACY:Motivation, Perseverance, Thoughts, Sources of Self-Efficacy

- COMMUNICATION:Historical Background, Informal-Formal, Interpersonal Communication

- COMMUNICATION (Part II):Downward Communication, Stereotyping Problems

- DECISION MAKING:History, Personal Rationality, Social Model, Conceptual

- PARTICIPATIVE DECISION MAKING TECHNIQUES:Expertise, Thinking skills

- JOB STRESS:Distress and Eustress, Burnout, General Adaptation Syndrome

- INDIVIDUAL STRESSORS:Role Ambiguity/ Role Conflict, Personal Control

- EFFECTS OF STRESS:Physical Effects, Behavioural Effects, Individual Strategies

- POWER AND POLITICS:Coercive Power, Legitimate Power, Referent Power

- POLITICS:Sources of Politics in Organizations, Final Word about Power

- GROUPS AND TEAMS:Why Groups Are Formed, Forming, Storming

- DYSFUNCTIONS OF GROUPS:Norm Violation, Group Think, Risky Shift

- JOB DESIGN:Job Rotation, Job Enlargement, Job Enrichment, Skill Variety

- JOB DESIGN:Engagement, Disengagement, Social Information Processing, Motivation

- LEARNING:Motor Learning, Verbal Learning, Behaviouristic Theories, Acquisition

- OBMOD:Applications of OBMOD, Correcting Group Dysfunctions

- LEADERSHIP PROCESS:Managers versus Leaders, Defining Leadership

- MODERN THEORIES OF LEADERSHIP PROCESS:Transformational Leaders

- GREAT LEADERS: STYLES, ACTIVITIES AND SKILLS:Globalization and Leadership

- GREAT LEADERS: STYLES, ACTIVITIES AND SKILLS:Planning, Staffing