|

Organizational

Psychology (PSY510)

VU

LESSON

24

HOPE

Rick

Synder defines hope as "a positive

motivational state; having will power

and way power"

Snyder

traced

the origins of his thinking to earlier

work by Averill, Catlin, and

Chon (1990) and Stotland

(1969), in

which

hope was cast in terms of

people's expectations that

goals could be achieved.

According to Snyder's

view,

goal-directed expectations are

composed of two separable

components. The first is

agency, and it

reflects

someone's determination that

goals can be achieved. The

second is identified as pathways:

the

individual's

beliefs that successful

plans can be generated to

reach goals. The second

component is Snyder's

novel

contribution, not found in

other formulations of optimism as an

individual difference.

Hope

so defined is measured with a

brief self-report scale (Snyder et

al., 1996). Representative

items, with

which

respondents agree or disagree, include

the following:

1.

I energetically pursue my goals.

[agency]

2.

There are lots of ways around any

problem. [Path ways]

Responses

to items are combined by averaging.

Scores have been examined

with respect to goal

expectancies,

perceived control, self-esteem,

positive emotions, coping, and

achievement, with results

as

expected

(e.g., Curry, Snyder, Cook,

Ruby, & Rehm, 1997; Irving,

Snyder, & Crowson,

1998).

�

Hope

is considered to be positively related to

a number of factors such

as:

�

Academic

achievement: The more

hopeful the candidate, the higher the

achievement.

�

Athletic

achievement: The more

hopeful the athlete, the better the

performance.

�

Emotional

health: Hopeful people have better

emotional stability and

overall emotional health.

�

Ability

to cope with illness:

Hopeful people fall less

sick.

�

And

hardships: Hopeful people cope better

with hardships and difficult

situations.

Happiness/Subjective

Well Being (SWB)

Subjective

well-being refers to all of the various

types of evaluation, both positive

and negative, that

people

make

of their lives. It includes reflective

cognitive evaluation, such as life

satisfaction and work

satisfaction,

interest

and engagement and effective

reactions to life events,

such as joy and sadness.

Thus, subjective

well-being

is an umbrella term for the different valuations

people make regarding their

lives, the events

happening

to them, their body and

mind, and the circumstances in

which they live. Although,

well-being

and

ill-being are "subjective" in the

sense that they occur within

a person's experience, manifestations

of

subjective

well-being and ill-being can be

observed objectively in verbal and

non-verbal behavior,

actions,

biology,

attention, and memory. The term

well-being is often used instead of

subjective well-being because

it

avoids any suggestion that

there is something arbitrary or

unknowable about eh concepts

involved.

Three

factors related to SWB

include:

Personality:

It is

one of the predictors of SWB.

Our

goals: Making

progress towards goals is

related to SWB.

Our

coping:

People tend to return to

their original level of SWB after coping

with different

adverse

situations.

Diener

and colleagues have

identified the following dimensions of

SWB:

Life

satisfaction

Life

satisfaction represents a report of

how a respondent evaluates or

appraises his or her life

taken as a

whole.

It is intended to represent a broad, reflective

appraisal the person makes of

his or her life. The

term

life

can be defined as all areas

of a person's life at a particular point

in time, or as an integrative judgment

about

the person's life since

birth, and this distinction is

often left ambiguous in current

measures.

Satisfaction

with important

domains

These

are judgments people make in evaluation

major life domains, such as

physical and mental

health,

work,

leisure, social relationships,

and family. Usually people indicate how

satisfied they are with

various

areas,

but they might also indicate

how much they like their

lives in each area, how

close to the ideal they

are

in each area, how much

enjoyment they experience in each area,

and how much they would

like to

change

their lives in each

area.

Positive

affect

Positive

affect denotes pleasant moods

and emotions, such as joy

and affection. Positive or

pleasant

emotions

are part of subjective well-being

because they reflect a person's reactions

to events that signify to

the

person that life is

proceeding in a desirable way.

Major categories of positive or

pleasant emotions

84

Organizational

Psychology (PSY510)

VU

include

those of low arousal (e.g.,

contentment), moderate arousal (e.g.,

pleasure), and high arousal

(e.g.,

euphoria).

They include positive reactions to

others, positive reactions to

activities, and general

positive

moods.

Negative

affect

Negative

affect includes moods and emotions

that are unpleasant, and

represent negative responses

people

experience

in reaction to their live, health, events

and circumstances. Major forms of

negative or unpleasant

reactions

include anger, sadness, anxiety and

worry, stress, frustration,

guilty and shame, and

envy. Other

negative

states, such as loneliness, or

helplessness, can also be

important indicators of ill-being.

Although

some

negative emotions are to be expected in

life and can be necessary

for effective functioning,

frequent

and

prolonged negative emotions indicate that

a person believes his or her

life proceeding badly.

Extended

experiences

of negative emotions can interfere

with effective functioning, as well as

make life unpleasant.

In

a research in 42 countries, involving

7240 subjects, 94% reported SWB to be

more important than

money.

People in poor nations show

average SWB scores close

to, or slightly below, the neutral

point.

Countries

that are wealthier possess

greater freedom and human rights,

and an emphasis on

individualism,

and

have citizens with higher

SWB (Diener, Diener, &

Diener, 1995) -- scoring

between slight and strong

SWB.

Surprisingly, other factors such as the

economic growth and the cultural

homogeneity of a society do

not

correlate with average

levels of SWB.

Although

reports of SWB are higher in

individualistic nations, the cultural dimension of

individualism

versus

collectivism produces complex effects.

Individualistic cultures are

those that emphasize

the

individual

-- her autonomy, motives,

and so forth. In contrast, in

collectivist cultures, the group (e.g.,

the

family)

is often considered more

important than the individual. There is

an emphasis on harmonious group

functioning,

and the belief that the

individual's motives and emotions should

be secondary. In individualistic

nations,

reports of global well-being are high,

and satisfaction with

domains such as marriage are

extremely

high.

Nevertheless, suicide rates

and divorce rates in these

same individualistic nations are

also high (Diener

&

Suh, in press-b). It may be

that people in individualistic nations

make more attributions for

events

internally

to themselves, and therefore the effects

are amplified when things go either well

or badly. It might

also

be that individualists are more

able to follow their own

interests and desires, and

therefore more often

find

self-fulfillment. At the same time, there

may be less social support

in individualistic cultures

during

troubled

periods. Furthermore, individualists are

more likely to get divorced, or

even commit suicide, if

things

do not go well. Thus, individualists may

experience more extreme

levels of SWB,

whereas

collectivists

may have a safer structure

that produces fewer people who

are very happy but perhaps

also

fewer

people who are isolated and

depressed. Our data support this

line of reasoning in that

not only do

individualistic

nations have higher suicide and divorce

rates, but they also have

higher reports of SWB.

In

adults, optimism, self-esteem, and

extraversion are several of the personality traits

possessed by happy

people.

For example, informant reports of

extraversion and sociability correlate

with the amount of pleasant

affect

that nursing home residents display.

Extraverts in a national probability

sample in the U.S.A.

who

lived

in a variety of different circumstances

experienced higher SWB (Diener,

Sandvik, Pavot, & Fujita,

1992).

It is useful, however, to differentiate the

separate components of SWB.

The two major forms of

affect,

pleasant and unpleasant,

appear to be related to the separate

personality factors of extraversion

and

neuroticism,

respectively. Although extraverts

experience more pleasant affect, they do

not experience a

predictable

level of unpleasant affect. Neurotics are

very likely to experience high

levels of unpleasant affect,

but

are less predictable when it comes to

levels of pleasant affect. When

measurement error is

controlled,

the

relations between these two

facets of affect and these

two personality dimensions are strong in

Western

nations.

What is not yet known is

whether extraversion predicts pleasant affect to the

same extent in

different

cultures such as in India or

Nepal.

Extraversion

and neuroticism are cardinal traits

that are part of a system of

personality labelled the Five

Factor

Model ( e.g., McCrae &

Costa, 1985). Two more

traits in this model, Agreeableness

and

Conscientiousness,

are correlated moderately

with SWB. Agreeableness and

Conscientiousness might

relate

to

SWB because of environmental

rewards. That is, in many or

most environments, people who

are

agreeable

and conscientious may

receive more positive

reinforcements from others,

and therefore may

experience

higher SWB. For example, a

conscientious person might

receive better grades in school,

better

pay

at work, and may even be

more likely to have a good

marriage. Thus, although

conscientiousness might

not

directly produce greater

SWB, it might result in

receiving rewards that heighten

one's SWB. If

85

Organizational

Psychology (PSY510)

VU

agreeableness

and conscientiousness are

related to SWB because of the

reinforcement structure, their

relation

to SWB may differ across

cultures.

The

fifth cardinal trait in the

Five Factor Model, Openness,

may relate to emotional intensity (having

both

intense

unpleasant and pleasant emotions) rather

than to hedonic balance. Larsen

and Diener (1987)

suggest

that

emotional intensity is a personality trait

that may influence the quality of

one's happiness -- whether

one

is likely to be elated versus

contented, or is distressed versus

melancholic.

SWB

is related to job satisfaction.

Job satisfaction and SWB

have a direct relationship. On the other

hand,

unemployment

causes lower SWB.

The

usual method of measuring

SWB is through self-report surveys in

which the respondent judges

and

reports

his life satisfaction, the

frequency of her pleasant affect, or the

frequency of his

unpleasant

emotions.

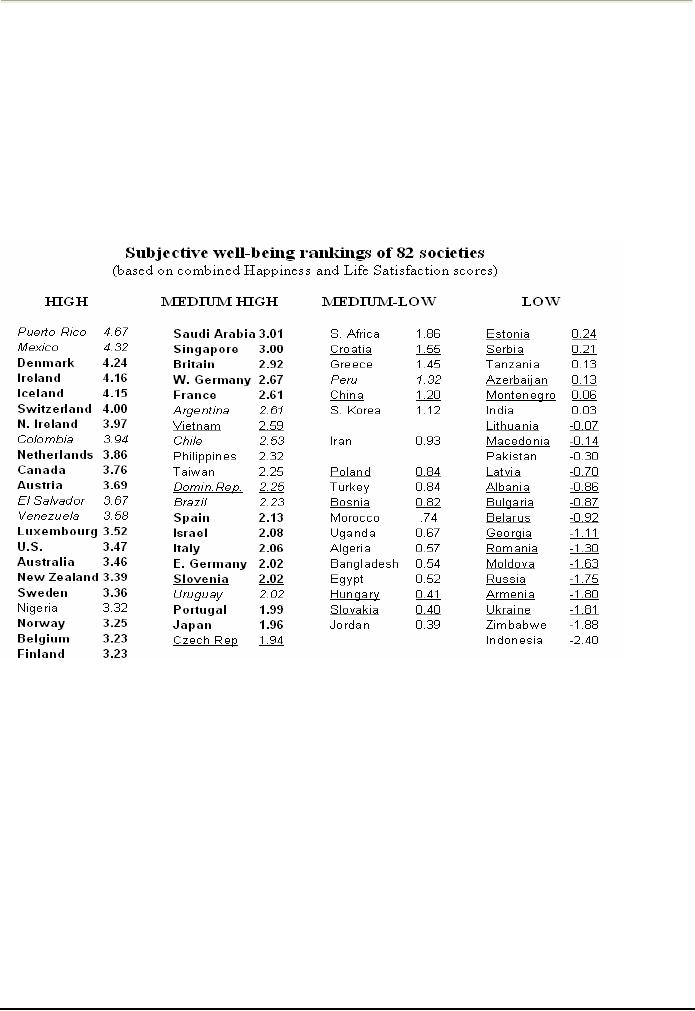

High-income

countries are shown in bold

face type. All 28 high-income countries

(in bold

type) rank

high

or

medium-high on subjective well-being; and

all 10 Latin American countries

(in italics)

except Peru also

rank

high or medium-high. All 25 ex-communist

countries (names underlined) except

Vietnam, Slovenia

and

Czech Republic are low or medium-low (the

median ex-communist country

has a negative score);

and

all

ten ex-Soviet countries are

Low (eight of the ten have negative

scores).

REFERENCES

�

Allman,

A. (1990). Subjective well-being of people

with disabilities: Measurement

issues. Unpublished

master's

thesis, University of

Illinois.

�

Andrews,

F. M., Robinson, J. P. (1991). Measures

of subjective well-being. In J. P. Robinson, P.

Shaver,

and

L. Wrightsman (Eds.) Measures of

Social Psychological Attitudes.

San Diego, CA: Academic

Press.

�

Beck,

A. T. (1967). Depression: Clinical,

experimental, and theoretical aspects.

New York: Hoeber.

�

Brickman,

P., Coates, D., & Janoff-Bulman, R.

(1978). Lottery winners and

accident victims: Is

happiness

relative? Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 36,

917-927.

�

A

Global Projection of Subjective

Well-being:

http://www.le.ac.uk/pc/aw57/world/sample.html

�

Diener-Guidelines

for National

Indicators.doc:www.wam.umd.edu/~cgraham/Courses/Docs/PUAF698R-Diener-

Guidelines%20for%20National%20Indicators.pdf

86

Organizational

Psychology (PSY510)

VU

�

Subjective

well-being rankings of 81

societies:

http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/Upload/5_wellbeingrankings.doc

FURTHER

READING

�

Recent

findings on subjective well

being

http://

www.psych.uiuc.edu/~ediener/hottopic/paper1.html

�

Researcher

on Subjective Well-Being. Department of Psychology �

University of Illinois at Urbana-

Champaign.

Personal Information: http://www.psych.uiuc.edu/~ediener

�

The

Anatomy of Subjective Well-being:

ideas.repec.org/p/dgr/uvatin/20020022.html

�

Subjective

well being: http://www.krueger.princeton.edu/Subjective.htm

�

A

definition of subjective well

being:

http://sprott.physics.wisc.edu/Lessons/paper263/tsld002.htm

87

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO ORGANIZATIONAL PSYCHLOGY:Hawthorne Effect

- METHODOLOGIES OF DATA COLLECTION:Observational method, Stability of Measures

- GLOBALIZATION:Aspects of Globalization, Industrial Globalization

- DEFINING THE CULTURE:Key Components of Culture, Individualism

- WHAT IS DIVERSITY?:Recruitment and Retention, Organizational approaches

- ETHICS:Sexual Harassment, Pay and Promotion Discrimination, Employee Privacy

- NATURE OF ORGANIZATIONS:Flat Organization, Neoclassical Organization Theory

- ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE:Academy Culture, Baseball Team Culture, Fortress Culture

- CHANGING ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE:Move decisively, defuse resistance

- REWARD SYSTEMS: PAY, Methods of Pay, Individual incentive plan, New Pay Techniques

- REWARD SYSTEMS: RECOGNITION AND BENEFITS, Efficiency Wage Theory

- PERCEPTION:How They Work Together, Gestalt Laws of Grouping, Closure

- PERCEPTUAL DEFENCE:Cognitive Dissonance Theory, Stereotyping

- ATTRIBUTION:Locus of Control, Fundamental Attribution Error

- IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT:Impression Construction, Self-focused IM

- PERSONALITY:Classifying Personality Theories, Humanistic/Existential

- PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT:Standardized, Basic Categories of Measures

- ATTITUDE:Emotional, Informational, Behavioural,Positive and Negative Affectivity

- JOB SATISFACTION:The work, Pay, Measurement of Job Satisfaction

- MOTIVATION:Extrinsic motive, Theories of work motivation, Safety needs

- THEORIES OF MOTIVATION:Instrumentality, Stacy Adams’S Equity theory

- MOTIVATION ACROSS CULTURES:Meaning of Work, Role of Religion

- POSITIVE PSYCHOLOGY:Criticisms of ‘Traditional’ Psychology, Optimism

- HOPE:Personality, Our goals, Satisfaction with important domains, Negative affect

- EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE:EI IS Related To Emotions and Intelligence

- SELF EFFICACY:Motivation, Perseverance, Thoughts, Sources of Self-Efficacy

- COMMUNICATION:Historical Background, Informal-Formal, Interpersonal Communication

- COMMUNICATION (Part II):Downward Communication, Stereotyping Problems

- DECISION MAKING:History, Personal Rationality, Social Model, Conceptual

- PARTICIPATIVE DECISION MAKING TECHNIQUES:Expertise, Thinking skills

- JOB STRESS:Distress and Eustress, Burnout, General Adaptation Syndrome

- INDIVIDUAL STRESSORS:Role Ambiguity/ Role Conflict, Personal Control

- EFFECTS OF STRESS:Physical Effects, Behavioural Effects, Individual Strategies

- POWER AND POLITICS:Coercive Power, Legitimate Power, Referent Power

- POLITICS:Sources of Politics in Organizations, Final Word about Power

- GROUPS AND TEAMS:Why Groups Are Formed, Forming, Storming

- DYSFUNCTIONS OF GROUPS:Norm Violation, Group Think, Risky Shift

- JOB DESIGN:Job Rotation, Job Enlargement, Job Enrichment, Skill Variety

- JOB DESIGN:Engagement, Disengagement, Social Information Processing, Motivation

- LEARNING:Motor Learning, Verbal Learning, Behaviouristic Theories, Acquisition

- OBMOD:Applications of OBMOD, Correcting Group Dysfunctions

- LEADERSHIP PROCESS:Managers versus Leaders, Defining Leadership

- MODERN THEORIES OF LEADERSHIP PROCESS:Transformational Leaders

- GREAT LEADERS: STYLES, ACTIVITIES AND SKILLS:Globalization and Leadership

- GREAT LEADERS: STYLES, ACTIVITIES AND SKILLS:Planning, Staffing