|

ADJUSTING TO CHRONIC ILLNESSES:Shock, Encounter, Retreat |

| << DEALING WITH PAIN:Acute Clinical Pain, Chronic Clinical Pain |

| THE COPING PROCESS IN PATIENTS OF CHRONIC ILLNESS:Asthma >> |

Health

Psychology PSY408

VU

Lesson

27

ADJUSTING

TO CHRONIC ILLNESSES

"It's

not fair" 12-year-old Joe

complained. Why can't I eat the

stuff I like? Other kids

can. Why do I have to

check

my blood everyday and take

shots? Nobody else has to do

that," He voiced these complaints as

he

left

the emergency room after suffering severe

stomach cramps because he

was not adhering to his

medical

regimen.

Hospital tests recently determined

that Joe has diabetes,

and he was not adjusting

well to the

regimen

his physician instructed him to

follow.

His

parents tried to explain

that not following the

regimen could have serious health

consequences, but he

thought,

`I'll do some of the things they say I

should do, and that'll be

enough. I feel fine--so

those

problems

won't happen to me." When

his noncompliance led to his being rushed

to the hospital with

severe

abdominal pain and difficulty breathing, he

finally believed the warnings he

received, and he began

to

adhere

closely to his

regimen.

Different

individuals react differently to

developing a chronic illness. Their

reactions depend on

many

factors,

such as their coping skills

and personalities, the social

support they have, the nature

and

consequences

of their illnesses, and the

impact of the illnesses on their daily

functioning. At the very least,

having

a chronic condition entails frequent

impositions on the patients and their

families. Chronically ill

people

may suffer periodic episodes of feeling

poorly and need to have

regular medical checkups,

restrict

their

diets or other aspects of

their life styles, or

administer daily treatment, for instance.

Many chronic

conditions

entail more than just

impositions-- they produce frequent pain

or lead to disability or

even

death.

This

and the next coming lectures

focus mainly on tertiary prevention

for chronic illness-- to retard

its

progression,

prevent disability, and rehabilitate the

person, physically and psychologically.

We will examine

how

people react to and cope

with chronic health problems and what

can be done to help these

people

cope

effectively.

The

present lecture concentrates on health

problems that are less

likely to result in death

but often lead to

disability.

We will begin by discussing people's

reactions to having a chronic condition,

then we will

examine

the experiences and needs of

individuals living with

various health problems, and

then we will

consider

psychosocial interventions to enhance

patients' long-term adaptation to their

conditions.

Our

discussion in these lectures

will address many questions

that are of great concern to

patients, to their

families

and friends, and probably to you.

How do individuals react after

their initial shock of learning

that

they

have a chronic illness? What kinds of

health problems usually involve the

most difficult

adjustments

for

people? How do patients' chronic

conditions impact on their

families? What can families,

friends, and

therapists

do to help chronically ill people adapt

effectively to their conditions?

Adjusting

To a Chronic Illness

I

felt like I'd been

hit in the stomach by a sledgehammer--this is

how many patients describe

their first

reaction

upon learning that they have a disabling

or life-threatening illness. Questions

without immediate

answers

flash through their minds:

Is the diagnosis right and, if

so, what can we do about it?

Will I be

disabled,

disfigured, or in pain? Will I die?

How soon will these

consequences happen? What

will happen to

my

family? Do I have adequate

medical and life insurance?

Learning of a chronic health problem

usually

comes

as a great shock, and this is

often the first reaction individuals

experience when the physician

tells

them

the diagnosis.

120

Health

Psychology PSY408

VU

Initial

Reactions on Having a Chronic

Condition

By

observing patients in rehabilitation and

health settings, Franklin Shontz

(1975) has described a

sequence

of

reactions people tend to exhibit

following the diagnosis of a serious

illness. This sequence of

reactions is:

1.

Shock--an

emergency response, marked by

three characteristics: {a) being

stunned or bewildered, (b)

behaving

in an automatic fashion, and (c) feeling

detached from the situation, that

is, feeling like being an

observer

rather than a participant in the events

that occur. The shock

may last only a short while

or may

continue

for weeks, occurs to some

degree in any crisis situation people

experience, and it is likely to

be

most

pronounced when the crisis comes without

warning.

2.

Encounter--a

phase that is marked by

disorganized thinking and

feelings of loss, grief,

helplessness,

despair,

and being overwhelmed by reality.

3.

Retreat--a

phase in which people tends to

use avoidance strategies,

such as denying either the

existence

of

the health problem or its implications.

But then reality begins to

intrude: the symptoms remain or

get

worse,

additional diagnoses confirm the

original one, and it becomes

clear that adjustments need

to be

made.

Using retreat as a "base of operation,"

patients tend to contact reality a

little at a time until they

reach

some

form of adjustment to the health problem

and its implications.

Do

all individuals react in the

ways Shontz has described

when they are faced with

such crises as being

diagnosed

with a serious illness? No,

but probably most do.

For instance, when faced

with a crisis, most

people

react with shock initially,

but other individuals may be

"cool and collected, while

others may be

"paralyzed"

with anxiety or may become hysterical".

Similarly, although many people with

serious illnesses

feel

extremely helpless and overwhelmed after

the initial shock, others do

dot. And many patients do

not

rely

heavily on avoidance strategies to cope

with the stress caused by having a health

problem.

People

who use denial and other

avoidance strategies do so to control

their emotional responses to

a

stressor,

especially when they believe they can do

nothing to change the situation. But the

usefulness of this

approach

has limits. Although using

avoidance strategies often provides

psychological benefits early in

the

process

of coping with health problems, excessive

avoidance can soon become

maladaptive to patients'

physical

and psychological well-being.

For

example, when hospitalized people receive

information about their

conditions and future risk

factors,

those

individuals who use

avoidance strategies heavily,

gain less information about

their conditions than

those

who use these strategies to

a lesser degree. Patients

often need to make major

decisions about their

immediate

treatment. How can they make

these decisions rationally if they

fail to take in the

information

that

the practitioners present to them? Later,

they may need to take action to

promote their recovery,

reduce

the likelihood of future health problems,

and adjust their lifestyles,

social relationships, and

means of

employment.

What factors influence how people

cope with their health

problems? The next

section

provides

some answers to this

question.

Influences

on Coping with Health

Crisis

Healthy

people tend to take their health

for granted. They expect to be

able to carry out their

daily activities

and

social roles from one

day to the next without

substantial disruptions due to illness.

When a serious

illness

or injury occurs, their

everyday life activities are disrupted.

Regardless of whether the condition

is

temporary

or chronic, the first phases in coping

with it are similar. But

there is an important difference:

in

contrast

to the short-term disruptions that temporary illnesses

cause, chronic health problems

usually

require

that patients and their

families make permanent behavioral,

social, and emotional

adjustments.

When

people learn that they have a

serious chronic illness, the diagnosis

quickly changes the way they

view

themselves

and their lives. The

plans they had for tomorrow

and for the next days,

weeks, and year may

be

121

Health

Psychology PSY408

VU

affected.

Major plans and minor

ones may change: Did they

plan to go on a trip this weekend? They

may

change

their minds now. Did they

plan to complete a college

education, or enter a specific

career field, or

get

married and have children, or

move to a new community when they

retire? Some of these ideas

for the

future

may evaporate after the

diagnosis.

As

psychologists Richard Lazarus

and Cohen have noted,

because the idea of being healthy, able,

and

having

a normal physique is central to most

people's image and evaluation,

becoming ill can be a shock

to a

persons

sense of security and to his

or her self-image. Not only

does it threaten the customary view

of

oneself,

but it further underscores

that one is indeed vulnerable;

and that one's life

may be changed in major

respects.

As a result adjustment to an illness or

injury which is life-threatening or

potentially disabling may

require

considerable coping effort. Potentially

disabling or life-threatening conditions

leave patients and

their

families with many

uncertainties, Often no one

can tell for certain

exactly what the course of the

illness

will

be.

The

Crisis Theory

Why

do some individuals cope

differently from others after learning

they have a chronic health

problem?

Rudolf

Moos (1986) has proposed the

crisis theory, which

describes factors that influence

how people

adjust

during a crisis, such as having an

illness.

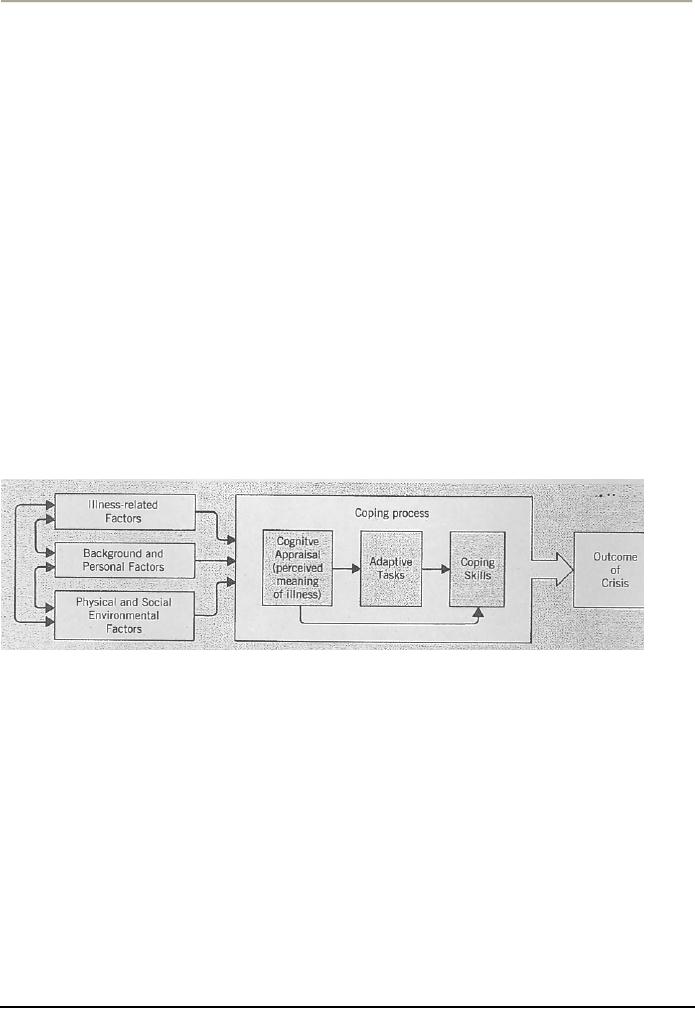

The

diagram presents his

conceptual model, showing that the

outcome of the crisis-- or the adjustment

the

person

makes--depends on the coping process,

which depends on three

contributing influences:

illness-

related

factors, background and personal

factors, and physical and

social environmental factors. We

will

look

at these contributing influences,

and then see how they affect the coping

process the patient

uses.

a)

Illness-Related Factors

Some

health problems present a greater threat

to the person than others

do--they may be more

disabling,

disfiguring,

painful, or life-threatening, for

example. As you might

expect, the greater the threats

patients

perceive

for any of these factors,

the more difficulty they are

likely to have coping with

their conditions.

Adjusting

to being disfigured can be extremely

difficult, particularly when it involves the

person's face.

Many

individuals whose faces are

badly scarred withdraw from

social encounters, sometimes

completely.

Often

people who see the disfigurement react

awkwardly, and some show

feelings of revulsion. Even

children

react more negatively to people's

facial disfigurements than to injuries to

other parts of the

body,

such

as when people are crippled or

missing a limb.

Patients

also have difficulty coping

with illness- related

factors that involve annoying or

embarrassing

changes

in bodily functioning or that

draw attention to their conditions.

People with some illnesses,

for

instance,

may need artificial devices

for excreting fecal or

urinary wastes. These

devices may be

noticeable

either

visibly or by their odors,

and many patients have

exaggerated impressions of the social

impact such

devices

have.

122

Health

Psychology PSY408

VU

Other

chronically ill people must treat their

conditions with ointments that

may have odors or

equipment

that

is visible or makes noise. Still

others may experience

periodic seizures or muscle

spasms that can be

embarrassing.

Many people with chronic illnesses feel

self-conscious about their health

problems--or even

stigmatized

by them--and want to hide them from

others.

Various

other aspects of treatment regimens

can make adjustment very

difficult, too. Some

treatments are

painful

or involve medications that produce

serious side effects--either by

leading to additional health

problems

or by interfering with the patient's

daily functioning, such as by making the

person immobile or

drowsy.

Other regimens may have

treatment schedules and time commitments

that make it difficult for

the

person

to find or hold a job. Some

regimens require patients and

their families to make

substantial changes

in

their lifestyles, which they

might resent and fail to

carry out. Each of these

factors can impair

people's

adjustment

to chronic health problems.

b)

Background and Personal

Factors

People

who cope well with chronic

health problems have the psychological

and behavioral resources to

resolve

the chronicity or `long-termness' of the situation,

balance hope against despair

and find purpose

and

quality

in life. Often, these people

have hardy or resilient personalities

that allow them to see a good

side in

difficult

situations.

People

with chronic diseases who

are resilient can often find

purpose and quality in their

lives, maintain

their

self-esteem, and resist feeling

helpless and

hopeless.

The

ways individuals cope with

chronic health problems also depend on

many other background

and

personal

factors, such as their age,

gender, social class, philosophical or

religious commitments, emotional

maturity

and self-esteem.

With

respect to gender differences,

for instance, men are

more likely than women to be

"threatened by the

decreases

in ambition, vigor, and

physical prowess that often

result from serious illness

because, by

comparison

with women, they are

confident in the stability of their

physical abilities and bodily

functioning.

Having

a chronic illness often means

that the individual must

take on a dependent and

passive role for a

long

period of time. For men, this

can be especially difficult

since it is inconsistent with the

assertive and

independent

roles they generally occupy in

most societies of the

world.

The

timing of a health problem in the

person's life span also

affects the impact on him or

her. In the case of

very

young children, their limited cognitive

abilities prevent them from understanding fully the

nature of

their

illnesses, the treatment regimens they

must follow, and the

long-term implications of their

conditions.

Their

concerns are likely to focus

on any restrictions that are

imposed on their lifestyles

and activities, the

frightening

medical procedures they experience,

and possible separations

from their parents. As

children get

older

and their comprehension improves they

may be able to participate in making some

decisions about

their

treatment.

c)

Physical and Social Environmental

Factors

Many

physical and social features

of our environments can affect the way we

adjust to chronic health

problems.

The physical aspects of a hospital

environment for instance,

are usually very dull and

confining

for

patients, thereby depressing their

general morale and mood.

For some individuals, the

home

environment

may not be much better.

Many patients have

difficulty getting around their houses

or

performing

self-help tasks; such as buttoning

clothes or opening food

containers, and lack

special

equipment

or tools that can help them

do these tasks and be more

self-sufficient. These people's

adjustment

to

their health problems can be impaired as

long as these situations

persist.

The

patient's social environment functions as

a system, with the behavior of

each person affecting the

others.

The presence of social support,

for example, generally helps

patients and their families

and friends

123

Health

Psychology PSY408

VU

cope

with their illnesses.

Individuals who live alone

and have few friends or who

have poor relationships

with

the people they live with tend to

adjust poorly to chronic health conditions.

But it is also true

that

sometimes

people in a patient's social network may

undermine effective coping by providing bad

examples

or

poor advice. The degree to

which each member of the

social system adjusts in constructive

ways to the

illness

affects the adjustment of the

others.

The

primary source of social support for

children and most adults

who are ill typically

comes from their

immediate

families. People in old age

whose spouses are either

deceased or unable to help

are likely to

receive

support mainly from their children, but

also from siblings, friends,

and neighbors. At almost

any

age,

patients may join support

groups for people with

specific medical problems.

These groups can

provide

informational

and emotional support.

As

the above given diagram depicts,

crisis theory's three contributing

influences are interrelated and

can

modify

each other. The patient's

social class or cultural background, for

instance, may affect his or

her self-

consciousness

about or access to special

devices and equipment to promote

self-sufficiency. These

contributing

factors combine to influence the coping process the

person uses to deal with the

crisis.

We

will talk about the coping process in

adjusting to chronic illnesses in our

next lecture. We will also

talk

about

the different chronic illnesses and

their biopsychosocial impacts on

patients.

124

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY:Health and Wellness Defined

- INTRODUCTION TO HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY:Early Cultures, The Middle Ages

- INTRODUCTION TO HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY:Psychosomatic Medicine

- INTRODUCTION TO HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY:The Background to Biomedical Model

- INTRODUCTION TO HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY:THE LIFE-SPAN PERSPECTIVE

- HEALTH RELATED CAREERS:Nurses and Physician Assistants, Physical Therapists

- THE FUNCTION OF NERVOUS SYSTEM:Prologue, The Central Nervous System

- THE FUNCTION OF NERVOUS SYSTEM AND ENDOCRINE GLANDS:Other Glands

- DIGESTIVE AND RENAL SYSTEMS:THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM, Digesting Food

- THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM:The Heart and Blood Vessels, Blood Pressure

- BLOOD COMPOSITION:Formed Elements, Plasma, THE IMMUNE SYSTEM

- SOLDIERS OF THE IMMUNE SYSTEM:Less-Than-Optimal Defenses

- THE PHENOMENON OF STRESS:Experiencing Stress in our Lives, Primary Appraisal

- FACTORS THAT LEAD TO STRESSFUL APPRAISALS:Dimensions of Stress

- PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF STRESS:Cognition and Stress, Emotions and Stress

- SOURCES OF STRESS:Sources in the Family, An Addition to the Family

- MEASURING STRESS:Environmental Stress, Physiological Arousal

- PSYCHOSOCIAL FACTORS THAT CAN MODIFY THE IMPACT OF STRESS ON HEALTH

- HOW STRESS AFFECTS HEALTH:Stress, Behavior and Illness, Psychoneuroimmunology

- COPING WITH STRESS:Prologue, Functions of Coping, Distancing

- REDUCING THE POTENTIAL FOR STRESS:Enhancing Social Support

- STRESS MANAGEMENT:Medication, Behavioral and Cognitive Methods

- THE PHENOMENON OF PAIN ITS NATURE AND TYPES:Perceiving Pain

- THE PHYSIOLOGY OF PAIN PERCEPTION:Phantom Limb Pain, Learning and Pain

- ASSESSING PAIN:Self-Report Methods, Behavioral Assessment Approaches

- DEALING WITH PAIN:Acute Clinical Pain, Chronic Clinical Pain

- ADJUSTING TO CHRONIC ILLNESSES:Shock, Encounter, Retreat

- THE COPING PROCESS IN PATIENTS OF CHRONIC ILLNESS:Asthma

- IMPACT OF DIFFERENT CHRONIC CONDITIONS:Psychosocial Factors in Epilepsy