|

Memory:Interference, Historical Memories, Recall versus Recognition |

| << Memory:Interference, The Critical Assumption, Limited capacity |

| Memory:Are forgotten memories lost forever? >> |

Cognitive

Psychology PSY 504

VU

Lesson

31

Memory

Interference

The

fan effect is the name

given to this increase in

reaction time related to an

increase in the

number

of facts associated with a

concept. It is so named because

the increase in reaction

time

is

related to an increase in the

fan of facts emanating from

the network representation of

the

concept.

The term conveys the

fact that additional

information about a concept

interferes with

memory

for a particular piece of

information. Interference affects a

wider range of measures

than

just

recognition time. Fan effect

is reserved for interference

effects as measured by reaction

time.

Historical

Memories

Lewis

& Anderson (1976) investigated

whether he fan effect could

be obtained with material

the

subject

knew before the experiment.

They had subjects learned

fantasy figures for

example,

Napoleon

Bonaparte was from India.

Subjects studied 0-4 fantasy

facts about each public

figure.

After

learning these facts they

proceeded to a recognition-test phase. In

this phase they

saw

three

types of sentences:

Fantasy

world statements, true

statements, and false

statements like

1)

Statements they had studied

in the experiment

2)

True facts about the

public figurers (such as

napoleon bonapartae was an

emperor);

3)

Statements about the public

figure that was false

both in the experimental

fantasy world

and

in the real world.

Subjects

had to respond to the first

two types of facts as true

and to the last type as

false.

Results

Subjects

responded much faster to

actual truths than to

experimental truths. The

advantage of

the

actual truths can be

explained, because these

true facts would be much

more strongly

encoded

in memory than the fantasy

facts because of greater

prior exposure. The more

fantasy

facts

one learned about a person,

the longer it took them to

recognize something they

already

knew

about the person; Napoleon

was an emperor.

Interference

and Retention

Now

we will consider what

happens as these interfering

effects get more

extreme-either because

the

to-be-recalled fact is very

weak or because the

interference is very

strong.

There

is evidence that the subject

simply fails to remember the

information under both

conditions.

Results

showing such failures of

memory have traditionally

been obtained with

paired-associate

material,

although similar results

have been obtained with

other material.

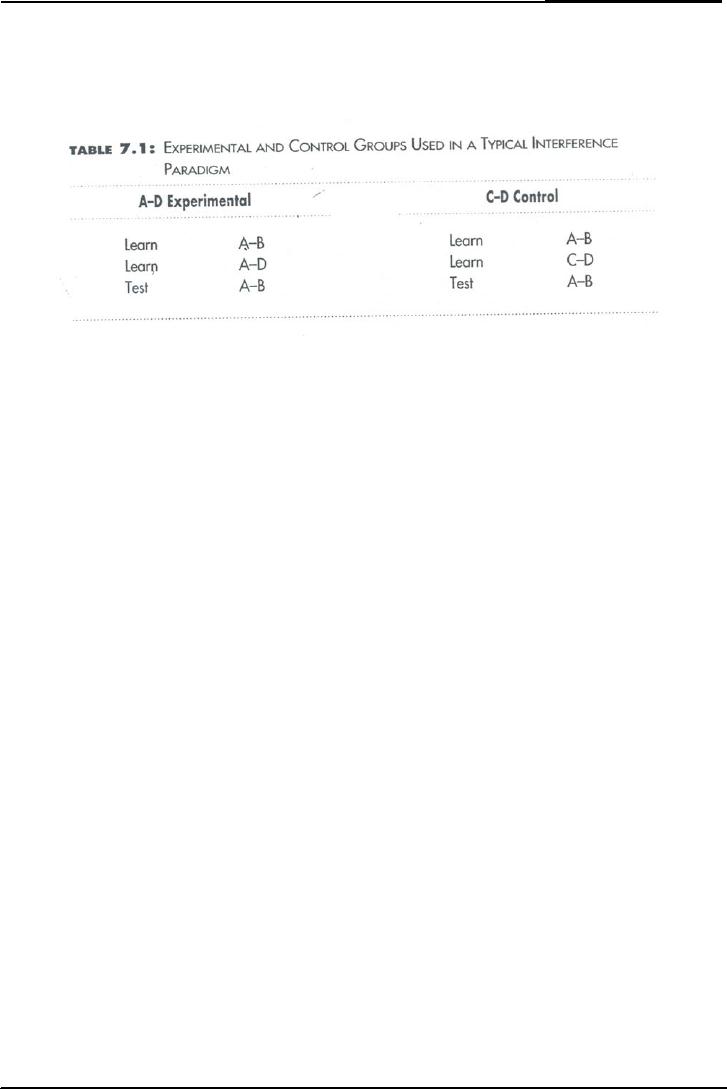

Experiment

In

a typical interference experiment,

two critical groups were

defined.

The

A-D experimental group

learns two lists of paired

associates,

The

first list is List

A-B: cat-43 and

house-61

And

second list is List

A-D: cat-82 and

house-37

The

C-D control group also

first studies the A-B

list, but then studies a

different second

list,

List

C-D is bone-82

and cup-37, which does

not contain the same

stimuli as the first

list.

After

learning their respective

second lists, both groups

are rested for their

memory of their first

list,

in both cases the A-B

list.

92

Cognitive

Psychology PSY 504

VU

Results

In

general, the A-D group

does not do as well as the

C-D group with respect to

both rate of

learning

of the second list and

retention of the original

A-B list.

The

results are presented in

following figure.

Implications

The

implication is that failure to

recall is the extreme case

of a long retrieval time.

Thus, it is not

the

case that the forgotten

information is not in memory,

but rather that it is in

memory but is too

weak

to be activated in the face of

interference from other

associations. Paired associate

memory

is

too weak to recall.

Forgetting

is not actual loss of

information but rather loss

of ability to activate that

information.

Recall

versus Recognition

Consistent

with the hypothesis that

there exists in memory

information that we can not

recall is

the

fact that we can recognize

many things we cannot

recall. This phenomenon

suggests that

information

can be in memory even though

it cannot be activated in the

recall test situation.

The

memory

network analysis makes clear

the reason that recognition

often works even when

recall

fails.

So, recognition is generally

better than recall. For

example if there is a

question

Who

invented the lenses we use

in spectacles?

Then

a huge fan of information

networks becomes active. We

recall a lot of information

that is

related

to glasses or spectacles.

For

example someone mention

Ibn-al Haitham invented the

lenses we use in spectacles. If

we

have

listened this before now,

then we can recall this

answer because of strong

enough

information.

So, Joint activation helps

the second statement.

There

are many other

possibilities. If with this

question (Who invented the

lenses we use in

spectacles?

we have some options like,

Michael, Ibne Batota,

Albaroni and Ibn Al Haitham.

Now

these

options interfere with our

information. And we become confuse.

But because of our links

or

network

we can recall correct

information. Like spectacles

were invented by Muslim

scientist so,

Michael

could not be answer.

So,

recognition is typically better

than recall because a

recognition test typically

provides more

sources

for activating memory.

Recognition test is better

than recall test. Tip of

the tongue is

happened

in recall not in

recognition.

For

example, if you see a man

you say you have

seen him before. So you

can recognize him.

But

you

are not recalling his

name.

In

our daily life, in our

exams, in any test or in

other situation we think

recognition is our friend

and

recall

is not much friendly.

93

Cognitive

Psychology PSY 504

VU

Another

example is if someone asks

you when Baber came in

Hindustan and invaded

Hindustan.

The

chances are we could not

recall. If someone gives us

some options like, 712,

789, 1566 and

1020

with question. Then it

becomes easy to recognize

when Baber invaded

India.

So

the conclusion of all that

is recognition is a better and

easiest task than

recall.

94

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION:Historical Background

- THE INFORMATION PROCESSING APPROACH

- COGNITIVE NEUROPSYCHOLOGY:Brains of Dead People, The Neuron

- COGNITIVE NEUROPSYCHOLOGY (CONTINUED):The Eye, The visual pathway

- COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY (CONTINUED):Hubel & Wiesel, Sensory Memory

- VISUAL SENSORY MEMORY EXPERIMENTS (CONTINUED):Psychological Time

- ATTENTION:Single-mindedness, In Shadowing Paradigm, Attention and meaning

- ATTENTION (continued):Implications, Treisman’s Model, Norman’s Model

- ATTENTION (continued):Capacity Models, Arousal, Multimode Theory

- ATTENTION:Subsidiary Task, Capacity Theory, Reaction Time & Accuracy, Implications

- RECAP OF LAST LESSONS:AUTOMATICITY, Automatic Processing

- AUTOMATICITY (continued):Experiment, Implications, Task interference

- AUTOMATICITY (continued):Predicting flight performance, Thought suppression

- PATTERN RECOGNITION:Template Matching Models, Human flexibility

- PATTERN RECOGNITION:Implications, Phonemes, Voicing, Place of articulation

- PATTERN RECOGNITION (continued):Adaptation paradigm

- PATTERN RECOGNITION (continued):Gestalt Theory of Perception

- PATTERN RECOGNITION (continued):Queen Elizabeth’s vase, Palmer (1977)

- OBJECT PERCEPTION (continued):Segmentation, Recognition of object

- ATTENTION & PATTERN RECOGNITION:Word Superiority Effect

- PATTERN RECOGNITION (CONTINUED):Neural Networks, Patterns of connections

- PATTERN RECOGNITION (CONTINUED):Effects of Sentence Context

- MEMORY:Short Term Working Memory, Atkinson & Shiffrin Model

- MEMORY:Rate of forgetting, Size of memory set

- Memory:Activation in a network, Magic number 7, Chunking

- Memory:Chunking, Individual differences in chunking

- MEMORY:THE NATURE OF FORGETTING, Release from PI, Central Executive

- Memory:Atkinson & Shiffrin Model, Long Term Memory, Different kinds of LTM

- Memory:Spread of Activation, Associative Priming, Implications, More Priming

- Memory:Interference, The Critical Assumption, Limited capacity

- Memory:Interference, Historical Memories, Recall versus Recognition

- Memory:Are forgotten memories lost forever?

- Memory:Recognition of lost memories, Representation of knowledge

- Memory:Benefits of Categorization, Levels of Categories

- Memory:Prototype, Rosch and Colleagues, Experiments of Stephen Read

- Memory:Schema Theory, A European Solution, Generalization hierarchies

- Memory:Superset Schemas, Part hierarchy, Slots Have More Schemas

- MEMORY:Representation of knowledge (continued), Memory for stories

- Memory:Representation of knowledge, PQ4R Method, Elaboration

- Memory:Study Methods, Analyze Story Structure, Use Multiple Modalities

- Memory:Mental Imagery, More evidence, Kosslyn yet again, Image Comparison

- Mental Imagery:Eidetic Imagery, Eidetic Psychotherapy, Hot and cold imagery

- Language and thought:Productivity & Regularity, Linguistic Intuition

- Cognitive development:Assimilation, Accommodation, Stage Theory

- Cognitive Development:Gender Identity, Learning Mathematics, Sensory Memory