|

COMMUNICATION MODELS – GRAPHIC PRESENTATION OF COMPLEX ISSUES |

| << ELEMENTS OF COMMUNICATION AND EARLY COMMUNICATION MODELS |

| TYPES AND FORMS OF COMMUNICATION:Inter personal, Combination >> |

Introduction

to Mass Communication MCM

101

VU

LESSON

05

COMMUNICATION

MODELS GRAPHIC PRESENTATION OF

COMPLEX ISSUES

True,

the Shannon-Weaver's model received

attention of communication experts but as

we know

Shannon

was not working to bring the

communication as we understand the term for

exchange of

messages

for human consumption, in the form of a

model. His endeavor was more

on the engineering side

where

he was trying to put the

elements of communication like the

encoder and decoder along

with channel

in

some logical sequence. To his

own extent he was successful.

But it also showed way to

communicators of

information

in daily life how to manipulate different

elements of communication graphically.

The

major missing point or the drawback in

Shannon-Weaver's model was that it

showed little concern

on

the

interpretation of the message. In a

mechanical way he was more

interested in decoding a message.

But,

as

students of communication will agree,

interpreting a message to give it meaning

for a person, who is

denoted

as receiver, is entirely a different

process. There is no decoder invented so

far which could

decode

meaning

of a human message to the extent as it is

meant by the source of the

sender.

This

huge gap remained a point of

concern by many till Schramm

and Osgood developed a model by

basically

modifying the Shannon weaver's model by

adding the elements of decoding in the

sense of

interpretation

and giving the process of communication a

much desired loop, circle,

in the form of

feedback.

Before

we continue talking Schramm's model lets

have a break and see communication

models from a

different

angle:

Advantages

of Models

Should

give general

perspective

A

good model is useful, then, in providing

both general perspective and

particular vantage points

from

which to ask questions and

to interpret the raw stuff of

observation. The more complex the

subject

matter--the

more amorphous and elusive

the natural boundaries--the greater are

the potential rewards of

model

building.

Should

clarify complexity

Models

also clarify the structure of complex

events. They do this, as well known

communication

scholar,

Chapanis (1961) noted, by reducing

complexity to simpler, more familiar

terms. Thus, the aim of

a

model

is not to ignore complexity or to explain it

away, but rather to give it order

and coherence.

Should

lead us to new

discoveries

According

to Mortensen, another prominent scholar, at another

level models have scientific value;

that

is,

they provide new ways to

conceive of hypothetical ideas

and relationships. This may

well be their most

important

function. With the aid of a

good model, suddenly we are jarred

from conventional modes

of

thought.

Ideally, any model, even when

studied casually, should offer

new insights and culminate

in what

can

only be described as an "Aha!"

experience.

Limitations

of Models

But

studying various aspects of communication

through models is not devoid

of certain drawbacks.

Here

are few points to keep in

mind.

a.

Can lead to over

simplifications

There

is no denying that much of the work in

designing communication models

illustrates the

often-repeated

charge that anything in

human affairs which can be

modeled is by definition too

superficial

to

be given serious consideration.

We

can guard against the risks

of over simplification by recognizing the

fundamental distinction between

simplification

and over-simplification. By definition,

and of necessity, models

simplify. So do all

14

Introduction

to Mass Communication MCM

101

VU

comparisons.

As Kaplan (1964) noted, "Science

always simplifies; its aim is

not to reproduce the reality in

all

its complexity, but only to

formulate what is essential for

understanding, prediction, or control

that a

model

is simpler than the subject-matter being

inquired into.

b.

Can lead to a confusion of the

model between the behaviors

it portrays

Mortensen:

Critics also charge that

models are readily confused

with reality. The problem

typically

begins

with an initial exploration of

some unknown territory....Then the model

begins to function as a

substitute

for the event: in short, the map is

taken literally. And what is

worse, another form of ambiguity

is

substituted

for the uncertainty the map was

designed to minimize. What has

happened is a sophisticated

version

of the general semanticist's admonition

that "the map is not the

territory." Spain is not

pink because

it

appears that way on the map,

and Minnesota is not up

because it is located near the

top of a United

States

map.

"The

proper answer lies in acquiring

skill in the art of map

reading."

c.

Premature Closure

The

model designer may escape the

risks of oversimplification and

map reading and still

fall prey to

dangers

inherent in abstraction. To press

for closure is to strive for a

sense of completion in a

system.

The

danger is that the model limits

our awareness of unexplored

possibilities of conceptualization. We

tinker

with the model when we might be better

occupied with the subject-matter itself.

Building a model, in

short,

may crystallize our thoughts at a

stage when they are better left in

solution, to allow new

compounds

to

precipitate

Having

seen this discussion by a range of

scholars, we continue to figure out

more about the model we have

chosen

for analysis.

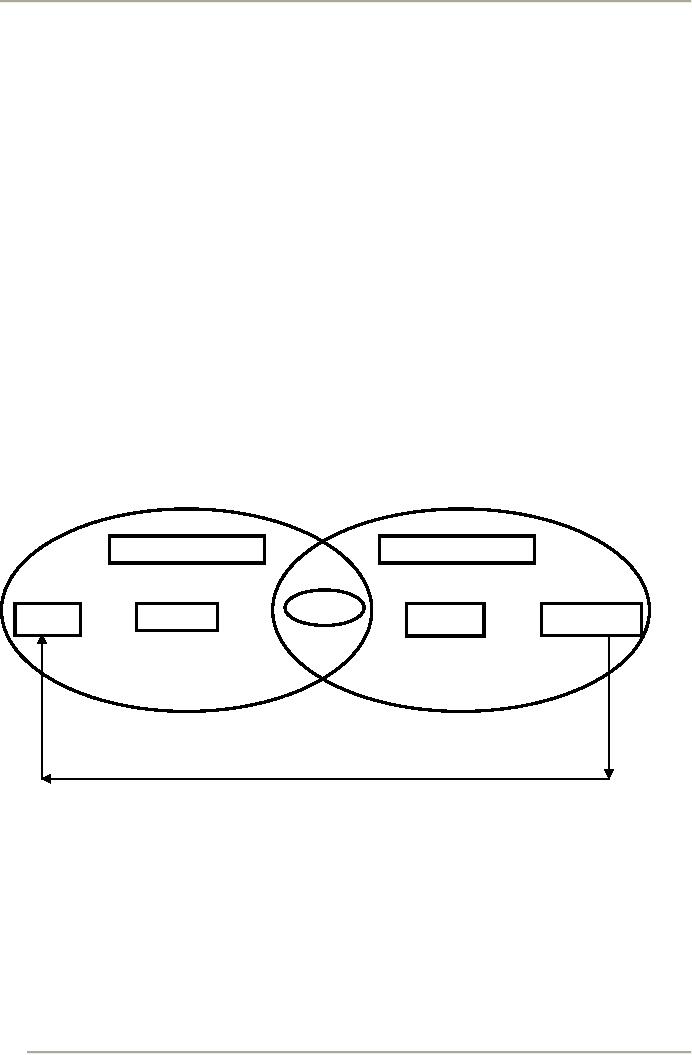

Schramm-Osgood's

Interactive Model,

1954

Field

of Experience

Field

of Experience

Signal

Source

Encoder

Decoder

Destination

Noise

15

Introduction

to Mass Communication MCM

101

VU

a.

Background

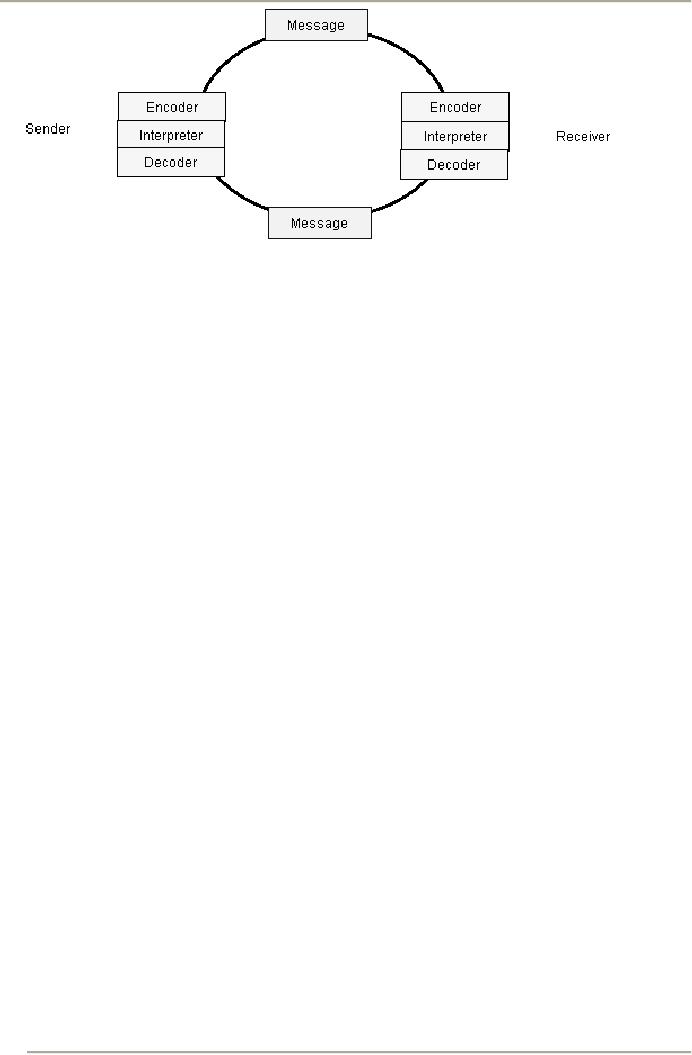

Wilbur

Schramm (1954) was one of

the first to alter the mathematical model of

Shannon and

Weaver.

He conceived of decoding and encoding as

activities maintained simultaneously by sender

and

receiver;

he also made provisions for a two-way

interchange of messages. Notice

also the inclusion of an

"interpreter"

as an abstract representation of the

problem of meaning.

The

strong points

1.

This model provided the additional notion

of a "field

of experience," or the

psychological frame of

reference;

this refers to the type of orientation or

attitudes that interacting people maintain

toward each

other.

2.

Included

Feedback

Communication

is reciprocal, two-way, even though the

feedback may be

delayed.

�

Some

of these methods of communication are

very direct,

as

when you talk in direct

response to

someone.

�

Others

are only moderately

direct; you

might squirm when a speaker

drones on and on, wrinkle

your

nose

and scratch your head when a

message is too abstract, or

shift your body position

when you

think

it's your turn to

talk.

�

Still

other kinds of feedback are completely

indirect.

Few

examples from our daily

life

�

Politicians

discover if they're getting their message

across by the number of votes

cast.

�

Commercial

sponsors examine sales

figures to gauge their communicative

effectiveness in ads.

�

Teachers

measure their abilities to get the

material across in a particular course by

seeing how many

students

sign up for it the next

term.

3.

Included

Context

A

message may have different

meanings, depending upon the specific

context or setting. Shouting

"Fire!"

on

a rifle range produces one

set of reactions, reactions

quite different from those

produced in a crowded

theater,

though the word is the same.

Culturally a message may

have different meanings

associated with it

depending

upon the culture or society. Communication

systems, thus, operate

within the confines of

cultural

rules and expectations to

which we all have been

educated.

Drawback

Schramm's

model, though less linear, still

accounts for only bilateral communication

between two

parties.

The complex, multiple levels

of communication between several sources

is beyond this model.

The

concepts of model carry some

more points to students of communication.

A few are mentioned below:

Entropy

Entropy

is the measure of uncertainty in a system.

Uncertainty or entropy increases in

exact

proportion

to the number of messages from which the

source has to choose. In the

simple matter of

flipping

a coin, entropy is low because the

destination knows the probability of a

coin's turning up either

16

Introduction

to Mass Communication MCM

101

VU

heads

or tails. In the case of a two-headed

coin, there can be neither

any freedom of choice nor

any

reduction

in uncertainty so long, as the destination knows

exactly what the outcome must

be. In other

words,

the value of a specific bit of

information depends on the probability

that it will occur. In

general, the

informative

value of an item in a message decreases

in exact proportion to the likelihood of

its occurrence.

Redundancy

Redundancy

is the degree to which information is

not unique in the system.

Those

items

in a message that add no new

information are redundant. Perfect

redundancy is equal to

total

repetition

and is found in pure form

only in machines. In human

beings, the very act of repetition

changes,

in

some minute way, the meaning

or the message and the larger

social significance of the event.

Zero

redundancy

creates sheer unpredictability,

for there is no way of

knowing what items in a sequence

will

come

next. As a rule, no message can reach

maximum efficiency unless it contains a

balance between the

unexpected

and the predictable, between what the

receiver must have

underscored to acquire

understanding

and

what can be deleted as

extraneous.

Noise

The

measure of information not

related to the message. "Any

additional signal that

interferes with

the

reception of information is noise. In

electrical apparatus noise

comes only from within the

system,

whereas

in human activity it may

occur quite apart from the

act of transmission and reception.

Interference

may

result, for example, from

background noise in the immediate

surroundings, from noisy

channels (a

crackling

microphone), from the organization and

semantic aspects of the message, or

from psychological

interference

with encoding and decoding.

Noise need not be considered

a detriment unless it produces

a

significant

interference with the reception of the message.

Even when the disturbance is

substantial, the

strength

of the signal or the rate of redundancy

may be increased to restore

efficiency.

Channel

Capacity

The

measure of the maximum amount of

information a channel can

carry. "The battle

against

uncertainty

depends upon the number of alternative possibilities

the message eliminates. Suppose

you want

to

know where a given checker

was located on a checkerboard. If

you start by asking if it is

located in the

first

black square at the extreme

left of the second row from

the top and find the answer

to be no, sixty-

three

possibilities remain-a high level of uncertainty. On

the other hand, if you first

ask whether it falls on

any

square at the top half of the board, the

alternative will be reduced by half

regardless of the answer. By

following

the first strategy it could be necessary

to ask up to sixty-three questions

(inefficient indeed!);

but

by

consistently halving the remaining

possibilities, you will

obtain the right answer in no

more than six

tries.

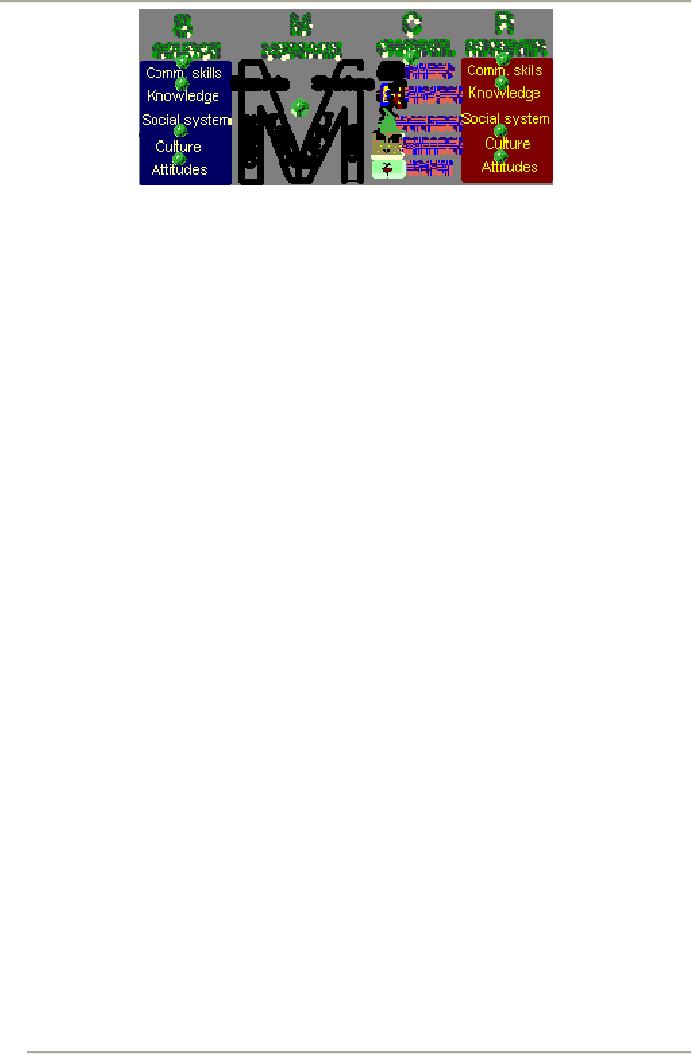

Berlo's

S-M-C-R Model

(1960)

David

Berlo's SMCR Model (1960)

proposes that there are

five elements within both

the

source/encoder

and the receiver/decoder which will

affect fidelity.

Source-Receiver

relationship

Berlo's

approach is rather different from what

seems to be suggested by the more

straightforward

transmission

models in that he places

great emphasis on dyadic communication,

therefore stressing the role

of

the relationship

between

the source and the receiver as an

important variable in the communication

process.

"A

given source may have a high

level of skill not shared by

one receiver, but shared by

another. We cannot

predict

the success of the source from

her skill level alone."

Berlo (1960)

17

Introduction

to Mass Communication MCM

101

VU

Communication

Skills

There

are five

verbal

communication skills, according to

Berlo:

Two

are encoding

skills:

�

speaking

�

writing

Two

are decoding

skills:

�

listening

�

reading

The

fifth is crucial to both encoding

and decoding:

�

thought

or

reasoning,

though you may perhaps

wish to object that to place

such emphasis on

reasoning,

what we generally think of as an intellectual

skill, to the detriment of emotion or

feeling,

is

unreasonable

As

encoders, our communication skills level

affects our communication fidelity in

two ways, according

to

Berlo:

�

It

affects our ability to

analyse our own purposes

and intentions, our ability

to say something when

we

communicate - you may

perhaps take issue with

Berlo on this, since it is

not apparent to all

of

us

that we necessarily use

verbal

skills

in reflecting on our purposes and

intentions.

�

It

affects our ability to

encode messages which say

what we intend. Our communication skills,

our

facility

for handling the language

code, affect our ability to

encode thoughts that we have.

We

certainly

all have experienced the

frustration of not being able to

find the 'right word' to

express

what

we want to say. Bearing in mind

Berlo's insistence on the dyadic

nature of communication, we

need

to remember that finding the

'right word' is not simply a

matter of finding one

which

expresses

what we want to say to our own

satisfaction. It also has to

have approximately the same

meaning

for the receiver as it does

for us.

Knowledge

level

Socio

Cultural systems

Attitudes

Message

(code, content, treatment)

Channel

(five senses)

18

Table of Contents:

- MASS COMMUNICATION – AN OVERVIEW:Relationships, Power

- EARLY MASS COMMUNICATION AND PRINTING TECHNOLOGY

- SEVEN CENTURIES OF MASS COMMUNICATION – FROM PRINTING TO COMPUTER

- ELEMENTS OF COMMUNICATION AND EARLY COMMUNICATION MODELS

- COMMUNICATION MODELS – GRAPHIC PRESENTATION OF COMPLEX ISSUES

- TYPES AND FORMS OF COMMUNICATION:Inter personal, Combination

- MESSAGE – ROOT OF COMMUNICATION I:VERBAL MESSAGE, Static Evaluation

- MESSAGE – ROOT OF COMMUNICATION II:Conflicts, Brevity of Message

- EFFECTS OF COMMUNICATION:Helping Out Others, Relaxation

- COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE:Enculturation, Acculturation

- LANGUAGE IN COMMUNICATION:Polarization, Labeling, Static meanings

- STEREOTYPING – A TYPICAL HURDLE IN MASS COMMUNICATION:Stereotype Groups

- MASS MEDIA – HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE:Early analysis on manuscripts

- EMERGENCE OF PRINT MEDIA AROUND THE WORLD:Colonial journalism

- TELEGRAPH DOES MIRACLE IN DISTANCE COMMUNICATION TELEX AND TELEPHONE ENTHRALL PRINT COMMUNICATION

- TYPES OF PRINT MEDIA:Newspapers, Magazines, Books

- PRESS FREEDOM, LAWS AND ETHICS – NEW DEBATE RAGING STILL HARD

- INDUSTRIALIZATION OF PRINT PROCESSES:Lithography, Offset printing

- EFFECTS OF PRINT MEDIA ON SOCIETY:Economic ideas, Politics

- ADVERTISING – HAND IN HAND WITH MEDIA:Historical background

- RENAISSANCE AND SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION: ROLE OF PRINT MEDIA:Science

- RECAP:Elements of communication, Books, Printing, Verbal Message

- MEDIA MANAGEMENT:Division, Business section, Press

- IMAGES IN MASS COMMUNICATION – INVENTION OF PHOTOGRAPHY:Portrait photography

- MOTION PICTURES – A NEW WAY IN MASS COMMUNICATION-I:Definition

- MOTION PICTURES – A NEW WAY IN MASS COMMUNICATION (Cont...):Post-Studio Era

- FILM MEDIA IN SUBCONTINENT AND PAKISTAN-I:Accusations of plagiarism

- FILM MEDIA IN SUBCONTINENT AND PAKISTAN (II) & ITS EFFECTS:First Color film

- PROPAGANDA:Types in another manner, Propaganda in revolutions

- RADIO – A BREAKTHROUGH IN MASS COMMUNICATION:What to broadcast

- EFFECTS OF RADIO ON SOCIETY:Entertainment, Information, Jobs

- TELEVISION – A NEW DIMENSION IN MASS COMMUNICATION:Early Discoveries

- TV IN PAKISTAN:Enthusiasm, Live Broadcast, PTV goes colored

- EFFECTS OF TELEVISION ON SOCIETY:Seeing is believing, Fashion

- PUBLIC RELATIONS AND MASS COMMUNICATION - I:History, Case Study

- PUBLIC RELATIONS AND MASS COMMUNICATION - II:Audience targeting

- ADVERTISING BEYOND PRINT MEDIA:Covert advertising

- IMPACT OF ADVERTISING:Trial, Continuity, Brand Switching, Market Share

- MEDIA THEORIES:Libertarian Theory, Social Responsibility Theory

- NEW MEDIA IN MASS COMMUNICATION:Technology forcing changes

- GLOBALIZATION OF MEDIA:Media and consumerism, Media centralization

- MEDIA MERGENCE:Radio, TV mergence, Economic reasons

- MASS MEDIA IN PRESENT AGE:Magazine, Radio, TV

- CRITICISM ON MEDIA:Sensationalize, Biasness, Private life, obscenity

- RECAP:Legends of South Asian Film Industry, Radio, Television, PTV goes colored