|

Introduction

to Mass Communication MCM

101

VU

LESSON

25

MOTION

PICTURES A NEW WAY IN MASS

COMMUNICATION-I

The

still photographs appeared frequently in

the print media by the third quarter of

the 19th century

and

the newspersons showed extra-ordinary

enthusiasm in exploiting the visual

strength of images

taken

through

camera. The quality of

images improved in the last quarter when

halftone technique was

discovered.

There

was hardly a world class

newspaper or magazine in the last

decade of the century which was

not

including

camera pictures to convey

one truth or the other to the

readers. Some of the camera

work, as

discussed

in the last lecture, was so strong

that it had forced the American government to

undertake

legislation

to help people living in

slums.

Not

only the darker side of the

life was in view of the

print media, the newspapers

and magazines were

fully

exploiting

the pictorial edge in the aesthetic

sense, especially playing up female

models. The trend

continues

to-date

and special fashion magazines

are a common sight at most

bookstalls. But scientists, inspired by

the

still

camera images, had some

other ideas as well. Why not to

create a sense of motion by

using a series of

images.

But how, was the question making them to

scratch their heads. At this

stage of history no one

knew

what

miracle in mass communication was in

waiting.

Definition

Motion

picture means movie-making as an art and an

industry, including its

production techniques,

its

creative artists and the

distribution and exhibition of

its products.

Start

in unbelievable fashion

It

started with a $25,000 bet,

in 1877 that was a lot of

money. Edward

Muybridge,

an Englishman tuned American, needed to settle a bet.

Some people argued

that

a galloping horse had all

four feet off of the ground at the

same time at some

point;

others

said this would be impossible. No feet

touching the ground; how could

that be?

The

problem was that galloping

hooves move too fast

for the eye to see. Or,

maybe,

depending

on your belief, just fast

enough that you could see what you

wanted to. To settle the

bet

definitive

proof was needed.

In an

effort to settle the issue

once and for all an

experiment was set up in which a

rapid sequence of

photos

was taken of a running horse.

When the pictures were developed it

was found that the horse

did

indeed

have all four feet off the

ground during brief moments,

thus, settling the bet. But, in

doing this

experiment

they found out something

else -- something that

becomes obvious from the illustrations

below.

When

a series of still photos are

presented sequentially, an illusion of

motion is created. That

discovery

would

soon make that $25,000

look like pocket

change.

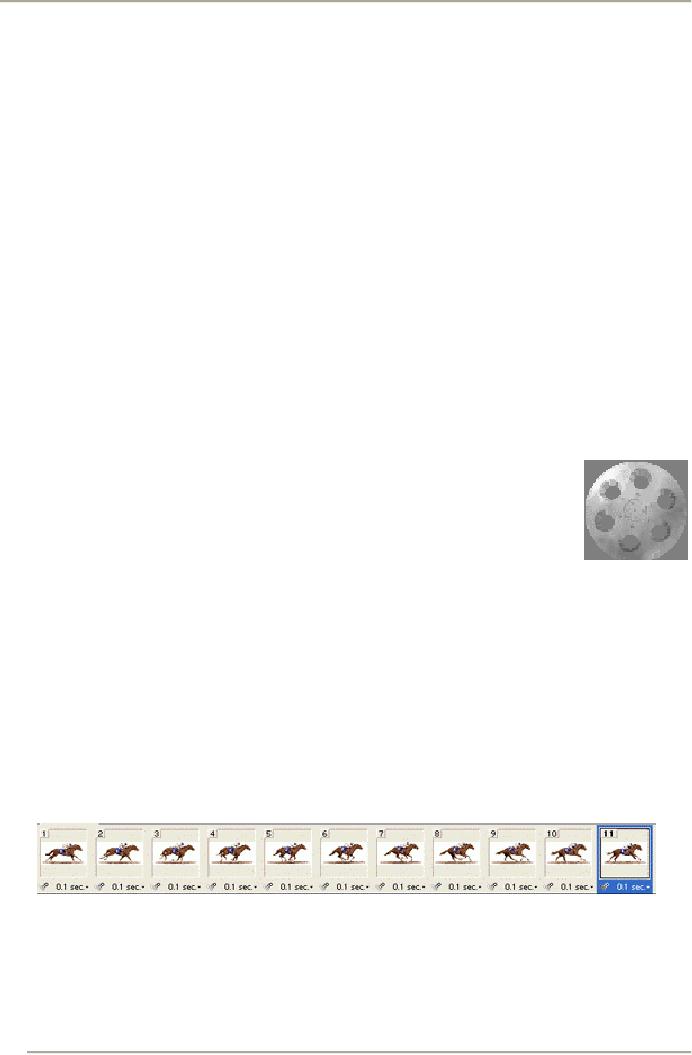

The

series of eleven still photos

shown below are presented

sequentially at 0.1 second intervals to

create the

appearance

of continuous motion.

Later,

we would give impressive names to the

two factors that created

this illusion of motion -- the

illusion

that

lies at the base of both

motion pictures and

television.

�

The

phi phenomenon that explains

why, when you view a

series of slightly different

still photos or

images

in rapid succession, an

illusion of movement is

created in the transition between the

images.

�

Persistence

of vision, which explains why the

intervals

between the successive images merge into

a single image

as

our eyes hold one

image long enough for the

next one to take its

place.

83

Introduction

to Mass Communication MCM

101

VU

In

actual fact, there is

nothing moving in motion

pictures. It's all an

illusion based on these two

phenomena.

Note

in the illustration on the left that an

illusion of motion is created,

even when successive

pictures are

presented

at a relatively slow rate.

Motion

picture projectors present images much

faster, at 24-frames per-second,

with each of those

frames

flashed

on the screen twice. This

high speed makes the

transition between images

virtually invisible. So, as

a

result

of a $25,000 bet, the foundation

for motion pictures and

television was inadvertently

established.

Early

days

Experiments

in photographing movement had been

made in both the United

States and Europe

during

the latter half of the 19th century with,

at first, no exploitation of its

technical and

commercial

possibilities.

Serial photographs of racehorses, intended to

prove that all four

hooves do leave the

ground

simultaneously,

were obtained (1867) in California by

Eadweard Muybridge and J. D.

Isaacs by setting up a

row

of cameras with shutters

tripped by wires. The first

motion pictures made with a

single camera were by

E.

J. Marey, a French physician, in the

1880s, in the course of his

study of motion.

In

1889 Thomas Edison and

his staff developed the kinetograph, a camera

using rolls of coated

celluloid

film,

and the Kinetoscope, a device for

peep-show viewing using photographs

that flipped in

sequence.

Marketed

in 1893, the Kinetoscope gained

popularity in penny arcades, and

experimentation turned to ways

in

which moving images might be

shown to more than one

person at a time. In France the

Lumi�re

brothers

created the first projection

device, the Cin�matographe (1895). In the

United States,

similar

machines,

notably the Pantopticon and the

Vitascope, were developed and

first used in New York

City in

1896.

At

first the screenings formed

part of variety shows and

arcades, but in 1902 a Los

Angeles shop that

showed

only moving pictures had

great success; soon "movie

houses" (converted shop-rooms) sprang

up

all

over the country. The first

movie theater, complete with

luxurious accessories and a piano,

was built in

Pittsburgh

in 1905. A nickel was charged

for admission, and the

theater was called the nickelodeon.

An

industry

developed to produce new material and the

medium's potential for

expressive ends began to

assert

itself.

The

first American studios were

centered in the New York

City area. Edison had

claimed the patents

for

many

of the technical elements involved in

filmmaking and, in 1909,

formed the Motion Picture

Patents

Company,

an attempt at monopoly that worked to

keep unlicensed companies

out of production and

distribution.

To put distance between

themselves and the Patents

Company's sometimes violent

tactics,

many

independents moved their operations to a suburb of Los

Angeles; the location's proximity to

Mexico

allowed

these producers to flee possible

legal injunctions. After

1913 Hollywood, Calif., became

the

American

movie capital. At first,

films were sold outright to

exhibitors; later they were distributed

on a

rental

basis through film

exchanges.

Early

on, actors were not

known by name, but in 1910,

the "star system" came into being

via promotion of

Vitagraph

Co. actress Florence

Lawrence, first known as The

Vitagraph Girl. Other

companies, noting

that

this

approach improved business,

responded by attaching names to

popular faces and "fan

magazines"

quickly

followed, providing plentiful,

and free, publicity. Films

had slowly been edging past

the 20 minute

mark,

but the drive to feature-length works

began with the Italian "spectacle"

film, of which Quo

Vadis

(1913),

running nine reels or about

two hours, was the most

influential.

Directors,

including D. W. Griffith, Thomas

Ince, Maurice Tourneur, J. Stuart

Blackton, and Mack

Sennett,

became

known to audiences as purveyors of

certain kinds, or "genres," of subject matter.

The first

generation

of star actors included Charlie Chaplin,

Buster Keaton, Mary

Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks,

Marie

Dressler,

Lillian Gish, William S.

Hart, Greta Garbo, John

Gilbert, Claudette Colbert,

Rudolph Valentino,

Janet

Gaynor, Ronald Colman, Clara

Bow, Gloria Swanson, Lon

Chaney, and Will Rogers.

During World

War

I the United States became

dominant in the industry and the moving

picture expanded into the

realm

of

education and

propaganda

84

Introduction

to Mass Communication MCM

101

VU

Subjects

in the beginning

The

earliest films were used

primarily to chronicle contemporary attitudes,

fashions, and events,

and

ran no longer than 10 minutes. At

first, simple actions were

filmed, then everyday scenes

and, pivotally,

gag

films, in which a practical joke is

staged as a simple tableau.

The camera was first

used in a fixed

position,

though soon it was pivoted,

or panned, on its tripod or moved

toward or away from a

subject.

The

medium's potential as a storytelling

mechanism was realized very

early in its history. The

Frenchman

George

M�li�s created the earliest special

effects and built elaborate

sets specifically to tell

stories of a

fantastic

nature, usually as a series of

tableaux. His Cinderella

(1900)

and A

Trip to the Moon (1902)

were major

innovative

accomplishments. The American Edwin S.

Porter demonstrated that action need

not be staged

for

cinema screen as for theater

and early realized that

scenes photographed in widely separate

locales could

be

cut, or edited, together yet still

not be confusing to the audience. His

subject matter tended

toward

depictions

of modern life; his Life

of an American Fireman (1902)

and The

Great Train Robbery (1903)

are among

the

first works to use editing as

well as acting and

stagecraft to tell their

stories.

Business

aspect

As

business increased, the demand

for product was met by

many new companies incorporated

to

create

the supply. Cooperation among the early

filmmakers yielded to the demands of the marketplace,

and

each

company tried to secure

continued success through

innovations meant to distinguish its

product. Out

of

these efforts developed the star

system, the establishment of physical

plants (studios) where the

films

would

be made, and the organization of the

filmmaking process into

interlocking crafts. The

crafts people

include

actors, producers, cinematographers,

writers, editors, and film

laboratory technicians who

work

interdependently

in a production effort overseen

and coordinated by the director.

The

year 1926 brought

experiments in sound effects

and music, and in 1927

spoken dialogue was

successfully

introduced in The

Jazz Singer with

Al Jolson. A year later the first

all-talking picture, Lights

of New

York,

was

shown. With the talkies new

directors achieved prominence--King

Vidor, Joseph Von

Sternberg,

Rouben

Mamoulian, Frank Capra, and

John Ford.

Sound

films gave a tremendous boost to the

careers of some silent actors

but destroyed many whose

voices

were

not suited to recording. Among the

most celebrated stars of the

new era were Clark Gable,

Jean

Harlow,

Marlene Dietrich, Mae West,

W. C. Fields, and the Marx Brothers.

Also in 1927 The

Motion

Picture

Academy of Arts and Sciences

was formed and began an

annual awards ceremony. The

prize, a

figurine

of a man grasping a star,

was later dubbed Oscar. These

awards did much to confer

status upon the

medium

in that they asserted a definable quality

of excellence analogous to literature and

theater, other

media

in which awards are given

for excellence. The Academy

Awards also offered the bonus of

gathering

many

stars in one place and

thus attracted immediate and

widespread attention. The

star system

blossomed:

actors

were recruited from the stage as

well as trained in the Hollywood

studios.

From

the 1930s until the early

1950s, the studios sponsored a

host of talented actors, foremost

among

whom

were Ingrid Bergman, Joan

Crawford, Bette Davis, Katharine Hepburn,

Charles Laughton,

Barbara

Stanwyck,

William Powell, Spencer Tracy,

Humphrey Bogart, Leslie Howard,

Gary Cooper, James

Stewart,

Cary

Grant, Irene Dunne, Edward

G. Robinson, Henry Fonda, Gregory Peck,

James Cagney, Judy

Garland,

Bob

Hope, James Mason, Fred Astaire, and Gene

Kelly. Producers and

directors such as David O.

Selznick,

Darryl

F. Zanuck, Mervyn LeRoy, William Wyler,

George Stevens, and Billy

Wilder made significant

contributions

to cinematic art.

To

be continued.......

85

Table of Contents:

- MASS COMMUNICATION – AN OVERVIEW:Relationships, Power

- EARLY MASS COMMUNICATION AND PRINTING TECHNOLOGY

- SEVEN CENTURIES OF MASS COMMUNICATION – FROM PRINTING TO COMPUTER

- ELEMENTS OF COMMUNICATION AND EARLY COMMUNICATION MODELS

- COMMUNICATION MODELS – GRAPHIC PRESENTATION OF COMPLEX ISSUES

- TYPES AND FORMS OF COMMUNICATION:Inter personal, Combination

- MESSAGE – ROOT OF COMMUNICATION I:VERBAL MESSAGE, Static Evaluation

- MESSAGE – ROOT OF COMMUNICATION II:Conflicts, Brevity of Message

- EFFECTS OF COMMUNICATION:Helping Out Others, Relaxation

- COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE:Enculturation, Acculturation

- LANGUAGE IN COMMUNICATION:Polarization, Labeling, Static meanings

- STEREOTYPING – A TYPICAL HURDLE IN MASS COMMUNICATION:Stereotype Groups

- MASS MEDIA – HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE:Early analysis on manuscripts

- EMERGENCE OF PRINT MEDIA AROUND THE WORLD:Colonial journalism

- TELEGRAPH DOES MIRACLE IN DISTANCE COMMUNICATION TELEX AND TELEPHONE ENTHRALL PRINT COMMUNICATION

- TYPES OF PRINT MEDIA:Newspapers, Magazines, Books

- PRESS FREEDOM, LAWS AND ETHICS – NEW DEBATE RAGING STILL HARD

- INDUSTRIALIZATION OF PRINT PROCESSES:Lithography, Offset printing

- EFFECTS OF PRINT MEDIA ON SOCIETY:Economic ideas, Politics

- ADVERTISING – HAND IN HAND WITH MEDIA:Historical background

- RENAISSANCE AND SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION: ROLE OF PRINT MEDIA:Science

- RECAP:Elements of communication, Books, Printing, Verbal Message

- MEDIA MANAGEMENT:Division, Business section, Press

- IMAGES IN MASS COMMUNICATION – INVENTION OF PHOTOGRAPHY:Portrait photography

- MOTION PICTURES – A NEW WAY IN MASS COMMUNICATION-I:Definition

- MOTION PICTURES – A NEW WAY IN MASS COMMUNICATION (Cont...):Post-Studio Era

- FILM MEDIA IN SUBCONTINENT AND PAKISTAN-I:Accusations of plagiarism

- FILM MEDIA IN SUBCONTINENT AND PAKISTAN (II) & ITS EFFECTS:First Color film

- PROPAGANDA:Types in another manner, Propaganda in revolutions

- RADIO – A BREAKTHROUGH IN MASS COMMUNICATION:What to broadcast

- EFFECTS OF RADIO ON SOCIETY:Entertainment, Information, Jobs

- TELEVISION – A NEW DIMENSION IN MASS COMMUNICATION:Early Discoveries

- TV IN PAKISTAN:Enthusiasm, Live Broadcast, PTV goes colored

- EFFECTS OF TELEVISION ON SOCIETY:Seeing is believing, Fashion

- PUBLIC RELATIONS AND MASS COMMUNICATION - I:History, Case Study

- PUBLIC RELATIONS AND MASS COMMUNICATION - II:Audience targeting

- ADVERTISING BEYOND PRINT MEDIA:Covert advertising

- IMPACT OF ADVERTISING:Trial, Continuity, Brand Switching, Market Share

- MEDIA THEORIES:Libertarian Theory, Social Responsibility Theory

- NEW MEDIA IN MASS COMMUNICATION:Technology forcing changes

- GLOBALIZATION OF MEDIA:Media and consumerism, Media centralization

- MEDIA MERGENCE:Radio, TV mergence, Economic reasons

- MASS MEDIA IN PRESENT AGE:Magazine, Radio, TV

- CRITICISM ON MEDIA:Sensationalize, Biasness, Private life, obscenity

- RECAP:Legends of South Asian Film Industry, Radio, Television, PTV goes colored