|

THEORY AND RESEARCH:Concepts, Propositions, Role of Theory |

| << CLASSIFICATION OF RESEARCH:Goals of Exploratory Research |

| CONCEPTS:Concepts are an Abstraction of Reality, Sources of Concepts >> |

Research

Methods STA630

VU

Lesson

4

THEORY

AND RESEARCH

The

purpose of science concerns the

expansion of knowledge, the discovery of

truth and to make

predictions.

Theory building is the means by

which the basic researchers hope to

achieve this purpose.

A

scientist poses questions like: What

produces inflation? Does student-teacher

interaction influence

students'

performance? In both these questions there is the

element of prediction i.e. that if we do

such

and

such, then so and so will

happen. In fact we are looking

for explanation for the

issue that has

been

raised

in these questions. Underlying the

explanation is the whole process

through which the

phenomenon

emerges, and we would like to understand

the process to reach

prediction.

Prediction

and understanding are the two

purposes of theory. Accomplishing the

first goal allows the

theorist

to predict the behavior or

characteristics of one phenomenon from the

knowledge of another

phenomenon's

characteristics. A business researcher

may theorize that older

investors tend to be more

interested

in investment income than

younger investors. This theory,

once verified, should

allow

researchers

to predict the importance of expected

dividend yield on the basis of

investors' age. The

researcher

would also like to understand the

process. In most of the situations

prediction and

understanding

the process go hand in hand i.e. to

predict the phenomenon, we must have an

explanation

of

why variables behave as they

do. Theories provide these

explanations.

Theory

As

such theory is a systematic

and general attempt to explain something

like: Why do people

commit

crimes?

How do the media affect us?

Why do some people believe

in God? Why do people

get

married?

Why do kids play truant

from school? How is our

identity shaped by culture?

Each of these

questions

contains a reference to some observed phenomenon. A

suggested explanation for the

observed

phenomenon

is theory. More formally, a

theory

is

a coherent set of general propositions,

used as

principles

of explanations of the apparent relationship of

certain observed phenomena. A key

element

in

this definition is the term

proposition.

A

systematic and

A

suggested

general

attempt to

explanation

for

explain

something...

something...

"Theory"

"Why

do people

"Why

do

commit

crimes?"

people

get

married?"

"How

does

the

"Why

do kids play truant

media

affect us?"

from

school?"

"Why

do some people

"How

is our identity

believe

in God?"

shaped

by culture?"

Concepts

Theory

development is essentially a process of

describing phenomena at increasingly

higher levels of

abstraction.

A concept

(or

construct) is a generalized idea about a

class of objects, attributes,

occurrences,

or processes that has been

given a name.

Such names are created or

developed or

constructed

for the identification of the phenomenon, be it

physical or non-physical. All these

may be

considered

as empirical realities e.g. leadership,

productivity, morale, motivation,

inflation, happiness,

banana.

11

Research

Methods STA630

VU

Concepts

are the building block of a

theory. Concepts abstract

reality. That is, concepts

are expressed in

words,

letters, signs, and symbols that refer to

various events or objects. For

example, the concept

"asset"

is an abstract term that may, in the

concrete world of reality,

refer to a specific punch

press

machine.

Concepts, however, may vary

in degree of abstraction and we can put

them in a ladder of

abstraction,

indicating different

levels.

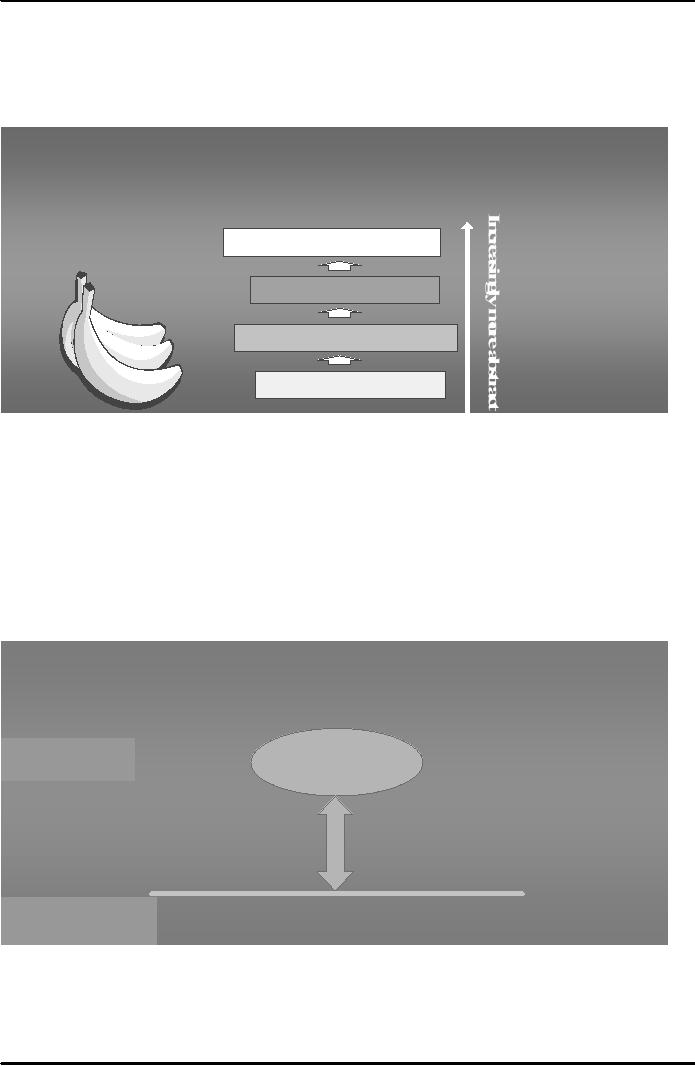

A

Ladder Of Abstraction

For

Concepts

Vegetation

Fruit

Banana

Reality

Moving

up the ladder

of abstraction, the

basic concept becomes more

abstract, wider in scope,

and

less

amenable to measurement. The

scientific researcher operates at

two levels: on the abstract

level of

concepts

(and propositions) and on the empirical

level of variables (and hypotheses). At the

empirical

level

we "experience" reality that is we

observe the objects or events. In

this example the reality

has

been

given a name i.e. banana.

Moving up the ladder this

reality falls in wider

reality i.e. fruit, which

in

turn

becomes part of further

wider reality called as

vegetation.

Researchers

are concerned with the observable

world, or what we may call

as "reality." We try to

construct

names to such empirical

reality for its

identification, which may

referred to as concept at an

abstract

level.

Concepts

are

Abstractions

of Reality

Abstract

CONCEPTS

Level

Empirical

OBSERVATION OF OBJECTS

Level

AND

EVENTS (REALITY)

Theorists

translate their conceptualization of

reality into abstract ideas.

Thus theory deals

with

abstraction.

Things are not the essence

of theory; ideas are.

Concepts in isolation are

not theories.

Only

when we explain how concepts

relate to other concepts we

begin to construct theories.

12

Research

Methods STA630

VU

Propositions

Concepts

are the basic units of

theory development. However, theories

require an understanding of the

relationship

among concepts. Thus, once reality is

abstracted into concepts, the scientist

is interested in

the

relationship among various concepts.

Propositions

are

statements concerned with the

logical

relationships

among concepts. A proposition explains

the logical linkage among certain

concepts by

asserting

a universal connection between

concepts.

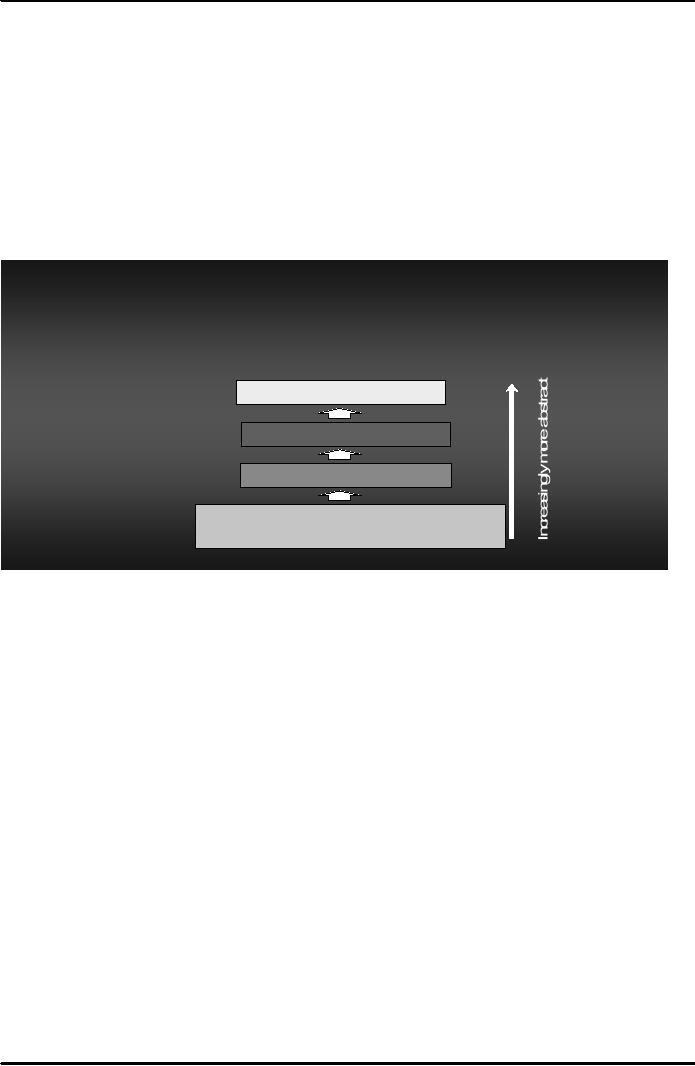

Theory

is an abstraction from observed reality.

Concepts are at one level of abstraction.

Investigating

propositions

requires that we increase our

level abstract thinking.

When we think about theories, we

are

at

the highest level of abstraction because

we are investigating the relationship

between propositions.

Theory

is a network of propositions.

Theory

Building Is A Process Of

Increasing

Abstraction

Theories

Propositions

Concepts

Observation

of objects

and

events (reality )

Theory

and Research

Basic

to modern science is an intricate

relation between theory and research.

The popular

understanding

of

this relationship obscures more

than it illuminates. Popular

opinion generally conceives of

these as

direct

opposites: theory is confused with

speculation, and thus theory

remains speculation until it

is

proved.

When this proof is made,

theory becomes fact. Facts

are thought to be definite,

certain, without

question,

and their meaning to be self

evident.

When

we look at what scientists

actually do when engaged in

research, it becomes clear (1)

that theory

and

fact are not diametrically

opposed, but inextricably

intertwined; (2) that theory

is not speculation;

and

(3) that scientists are

very much concerned with

both theory and fact

(research).

Hence

research produces facts and

from facts we can generate

theories. Theories are soft

mental images

whereas

research covers the

empirical world of hard, settled, and observable

things. In this way

theory

and

fact (research) contribute to

each other.

Role

of Theory

1.

Theory as orientation.

A

major function of a theoretical

system is that it narrows the range of

facts to be studied. Any

phenomenon

or object may be studied in

many different ways. A football,

for example, can be

investigated

within an economic framework, as we

ascertain the patterns of demand and

supply relating

to

this play object. It may

also be the object of chemical research,

for it is made of organic

chemicals.

It

has a mass and may be

studied as physical object

undergoing different stresses and

attaining certain

13

Research

Methods STA630

VU

velocities

under various conditions. It

may also be seen as the

center of many sociologically

interesting

activities

play, communication, group

organization, etc.

Each

science and each

specialization within a broader field

abstracts from reality,

keeping its attention

upon

a few aspects of given

phenomena rather than on all

aspects. The broad

orientation of each

field

then

focuses upon limited range of

things while ignoring or

making assumptions about

others.

2.

Theory as a conceptualization and

classification.

Every

science is organized by a structure of

concepts, which refer to

major processes and objects to be

studied.

It is the relationship between these

concepts which are stated in

"the facts of science."

Such

terms

make up the vocabulary that the scientist

uses. If knowledge is to be organized,

there must be

some

system imposed upon the facts

which are observable. As a consequence, a

major task in any

science

is the development of development of

classification, a structure of concepts, and an

increasingly

precise

set of definitions for these

terms.

3.

Theory in summarizing role.

A

further task which theory

performs is to summarize concisely what

is already known about the

object

of

study. These summaries may

be divided into two simple

categories: (1) empirical

generalizations,

and

(2) systems of relationships between

propositions.

Although

the scientist may think of his

field as a complex structure of

relationships, most of his

daily

work

is concerned with prior task: the

simple addition of data, expressed in

empirical generalizations.

The

demographer may tabulate births and

deaths during a given period

in order to ascertain the crude

rate

of reproduction. These facts

are useful and are

summarized in simple or complex

theoretical

relationships.

As body of summarizing statements

develops, it is possible to see relationships

between

thee

statements.

Theorizing

on a still larger scale,

some may attempt to integrate the

major empirical generalizations

of

an

era. From time to time in

any science, there will be

changes in this

It

is through systems of propositions

that many of our common

statements must be interpreted.

Facts

are

seen within a framework rather

than in an isolated

fashion.

4.

Theory predicts facts.

If

theory summarizes facts and

states a general uniformity beyond the

immediate observation, it

also

becomes

a prediction of facts. This

prediction has several facets.

The most obvious is the

extrapolation

from

the known to the unknown. For

example, we may observe that

in every known case

the

introduction

of Western technology has

led to a sharp drop in the death rate and

a relatively minor

drop

in

the birth rate of a given nation, at

least during the initial

stages. Thus we predict that if

Western

technology

is introduced into a native

culture, we shall find this

process again taking

place.

Correspondingly

we predict that in a region where

Western technology has

already been introduced,

we

shall

find that this process

has occurred.

5.

Theory points gaps in

knowledge.

Since

theory summarizes the known

facts and predicts facts

which have not been observed, it

must also

point

to areas which have not yet

been explored.

Theory

also points to gaps of a more

basic kind. While these

gaps are being filled,

changes in the

conceptual

scheme usually occur. An

example from criminology may

be taken. Although a substantial

body

of knowledge had been built

up concerning criminal behavior

and it causes. A body of

theory

dealing

with causation was oriented almost

exclusively to the crimes committed by

the lower classes.

Very

little attention has been

paid to the crimes committed by the

middle class or, more

specifically, to

the

crimes labeled as "white

collar" and which grow

out of the usual activities of

businessmen. Such a

gap

would not be visible if our

facts were not systematized

and organized. As a consequence, we

may

say

that theory does suggest

where our knowledge is

deficient.

Role

of Facts (Research)

Theory

and fact are in constant

interaction. Developments in one may

lead to developments in the

other.

Theory, implicit or explicit, is

basic to knowledge and even perception.

Theory is not merely

a

14

Research

Methods STA630

VU

passive

element. It plays an active role in the

uncovering of facts. We should expect

that "fact" has an

equally

significant part to play in the

development of theory. Science

actually depends upon

a

continuous

stimulation of fact by theory and of

theory by fact.

1.

Facts initiate theory.

Many

of the human interest stories in the history of

science describe how a

striking fact,

sometimes

stumbled

upon, led to important theories.

This is what the public

thinks of as a "discovery."

Examples

may

be taken from many sciences:

accidental finding that the penicillium

fungus inhibits

bacterial

growth;

many errors in reading, speaking, or

seeing are not accidental

but have deep and

systematic

causes.

Many of these stories take

an added drama in the retelling,

but they express a

fundamental fact

in

the growth of science, that an

apparently simple observation

may lead to significant

theory.

2.

Facts lead to the rejection

and reformulation of existing

theory.

Facts

do not completely determine

theory, since many possible theories

can be developed to

take

account

of a specific set of observation.

Nevertheless, facts are the more stubborn

of the two. Any

theory

must adjust to facts and is rejected or

reformulated if they cannot be fitted

into its structure.

Since

research is continuing activity,

rejection and reformulation are

likely to be going on

simultaneously.

Observations are gradually accumulated

which seem to cast doubt

upon existing

theory.

While new tests are

being planned, new

formulations of theory are

developed which might

fit

these

new facts.

3.

Facts redefine and clarify

theory.

Usually

thee scientist has investigated

his/her problem for a long

time prior to actual field or

laboratory

test

and is not surprised by his/her

results. It is rare that

he/she finds a fact that

simply does not fit

prior

theory.

New

facts that fit thee

theory will always redefine

the theory, for they state

in detail what the

theory

states

in very general terms. They

clarify that theory, for

they throw further light

upon its concepts.

Theory

and Research: the Dynamic

Duo

Theory

and research are

interrelated; the dichotomy between

theory and research is an

artificial. The

value

of theory and its necessity

for conducting good research

should be clear. Researchers

who

proceed

without theory rarely conduct

top-quality research and frequently

find themselves in

confusion.

Researchers

weave together knowledge from

different studies into more

abstract theory. Likewise,

who

proceed

without linking theory to

research or anchoring it to empirical

reality are in jeopardy of

floating

off

into incomprehensible speculation and

conjecture.

15

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION, DEFINITION & VALUE OF RESEARCH

- SCIENTIFIC METHOD OF RESEARCH & ITS SPECIAL FEATURES

- CLASSIFICATION OF RESEARCH:Goals of Exploratory Research

- THEORY AND RESEARCH:Concepts, Propositions, Role of Theory

- CONCEPTS:Concepts are an Abstraction of Reality, Sources of Concepts

- VARIABLES AND TYPES OF VARIABLES:Moderating Variables

- HYPOTHESIS TESTING & CHARACTERISTICS:Correlational hypotheses

- REVIEW OF LITERATURE:Where to find the Research Literature

- CONDUCTING A SYSTEMATIC LITERATURE REVIEW:Write the Review

- THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK:Make an inventory of variables

- PROBLEM DEFINITION AND RESEARCH PROPOSAL:Problem Definition

- THE RESEARCH PROCESS:Broad Problem Area, Theoretical Framework

- ETHICAL ISSUES IN RESEARCH:Ethical Treatment of Participants

- ETHICAL ISSUES IN RESEARCH (Cont):Debriefing, Rights to Privacy

- MEASUREMENT OF CONCEPTS:Conceptualization

- MEASUREMENT OF CONCEPTS (CONTINUED):Operationalization

- MEASUREMENT OF CONCEPTS (CONTINUED):Scales and Indexes

- CRITERIA FOR GOOD MEASUREMENT:Convergent Validity

- RESEARCH DESIGN:Purpose of the Study, Steps in Conducting a Survey

- SURVEY RESEARCH:CHOOSING A COMMUNICATION MEDIA

- INTERCEPT INTERVIEWS IN MALLS AND OTHER HIGH-TRAFFIC AREAS

- SELF ADMINISTERED QUESTIONNAIRES (CONTINUED):Interesting Questions

- TOOLS FOR DATA COLLECTION:Guidelines for Questionnaire Design

- PILOT TESTING OF THE QUESTIONNAIRE:Discovering errors in the instrument

- INTERVIEWING:The Role of the Interviewer, Terminating the Interview

- SAMPLE AND SAMPLING TERMINOLOGY:Saves Cost, Labor, and Time

- PROBABILITY AND NON-PROBABILITY SAMPLING:Convenience Sampling

- TYPES OF PROBABILITY SAMPLING:Systematic Random Sample

- DATA ANALYSIS:Information, Editing, Editing for Consistency

- DATA TRANSFROMATION:Indexes and Scales, Scoring and Score Index

- DATA PRESENTATION:Bivariate Tables, Constructing Percentage Tables

- THE PARTS OF THE TABLE:Reading a percentage Table

- EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH:The Language of Experiments

- EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH (Cont.):True Experimental Designs

- EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH (Cont.):Validity in Experiments

- NON-REACTIVE RESEARCH:Recording and Documentation

- USE OF SECONDARY DATA:Advantages, Disadvantages, Secondary Survey Data

- OBSERVATION STUDIES/FIELD RESEARCH:Logic of Field Research

- OBSERVATION STUDIES (Contd.):Ethical Dilemmas of Field research

- HISTORICAL COMPARATIVE RESEARCH:Similarities to Field Research

- HISTORICAL-COMPARATIVE RESEARCH (Contd.):Locating Evidence

- FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSION:The Purpose of FGD, Formal Focus Groups

- FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSION (Contd.):Uses of Focus Group Discussions

- REPORT WRITING:Conclusions and recommendations, Appended Parts

- REFERENCING:Book by a single author, Edited book, Doctoral Dissertation