|

CONSUMPTION (Continued…):Consumer Preferences, Constraints on Borrowings |

| << CONSUMPTION:Secular Stagnation and Simon Kuznets |

| CONSUMPTION (Continued…):The Life-cycle Consumption Function >> |

Macroeconomics

ECO 403

VU

LESSON

38

CONSUMPTION

(Continued...)

Consumer's

Budget Constraint

Irving

Fisher's generalization:

C2

Y2

C1

+

r

+

1+r

=

Y1 +

1

So

we can say that

�

�

The

consumer's budget constraint

implies that if the interest

rate is zero, the

budget

constraint

shows that total consumption

in the two periods equals

total income in the

two

periods. In the usual case

in which the interest rate

is greater than zero,

future

consumption

and future income are

discounted by a factor of 1 + r.

�

This

discounting

arises

from the interest earned on

savings. Because the

consumer

earns

interest on current income

that is saved, future income

is worth less than

current

income.

�

Also,

because future consumption is

paid for out of savings

that have earned

interest,

future

consumption costs less than

current consumption.

�

The

factor 1/(1+r) is the price

of second-period consumption measured in

terms of first-

period

consumption; it is the amount of

first-period consumption that

the consumer

must

forgo to obtain 1 unit of

second-period consumption.

Second-period

consumption

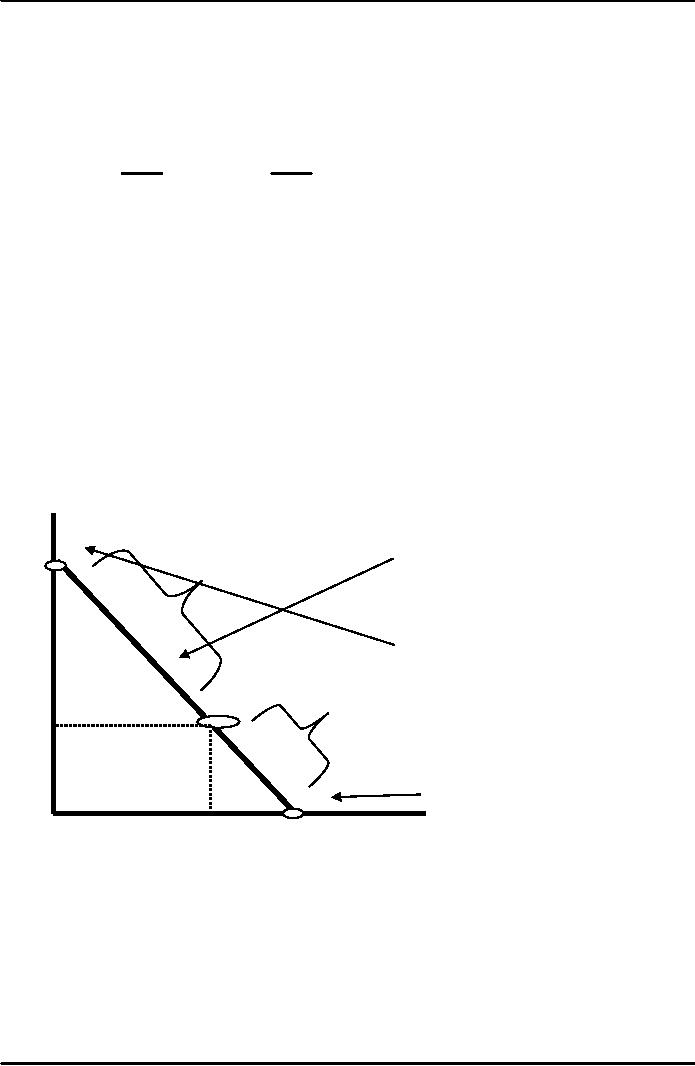

B

Consumer's

budget

constraint

Saving

Vertical

intercept is

(1+r)Y1 +

Y2

A

Borrowing

Y2

Horizontal

intercept is

C

Y1 +

Y2/(1+r)

Y1

First-period

consumption

If

he chooses a point between A

and B, he consumes less than

his income in the first

period

and

saves the rest for

the second period. If he

chooses between A and C, he

consumes more

that

his income in the first

period and borrows to make

up the difference.

178

Macroeconomics

ECO 403

VU

Consumer

Preferences

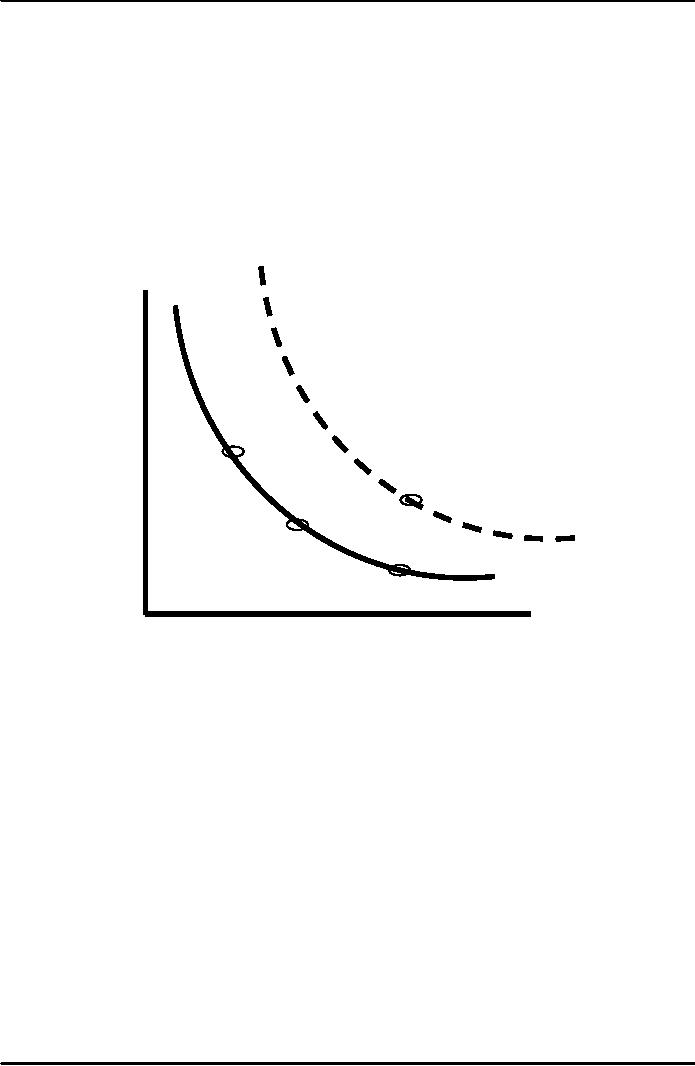

The

consumer's preferences regarding

consumption in the two

periods can be represented

by

indifference

curves.

An

indifference curve shows the

combination of first-period and

second-period consumption

that

makes the consumer equally

happy.

�

The

slope at any point on the

indifference curve shows how

much second-period

consumption

the consumer requires in

order to be compensated for a

1-unit reduction in

first-period

consumption. This slope is

the marginal rate of

substitution between

first-period

consumption

and second-period consumption. It

tells us the rate at which

the consumer is

willing

to substitute second-period consumption

for first-period

consumption.

Second-period

consumption

Y

Z

IC2

X

IC1

W

First-period

consumption

Higher

indifferences curves such as

IC2 are preferred to lower

ones such as IC1. The

consumer

is

equally happy at points W, X, and Y,

but prefers Z to all the

others-- Point Z is on a

higher

indifference

curve and is therefore not

equally preferred to W, X and Y.

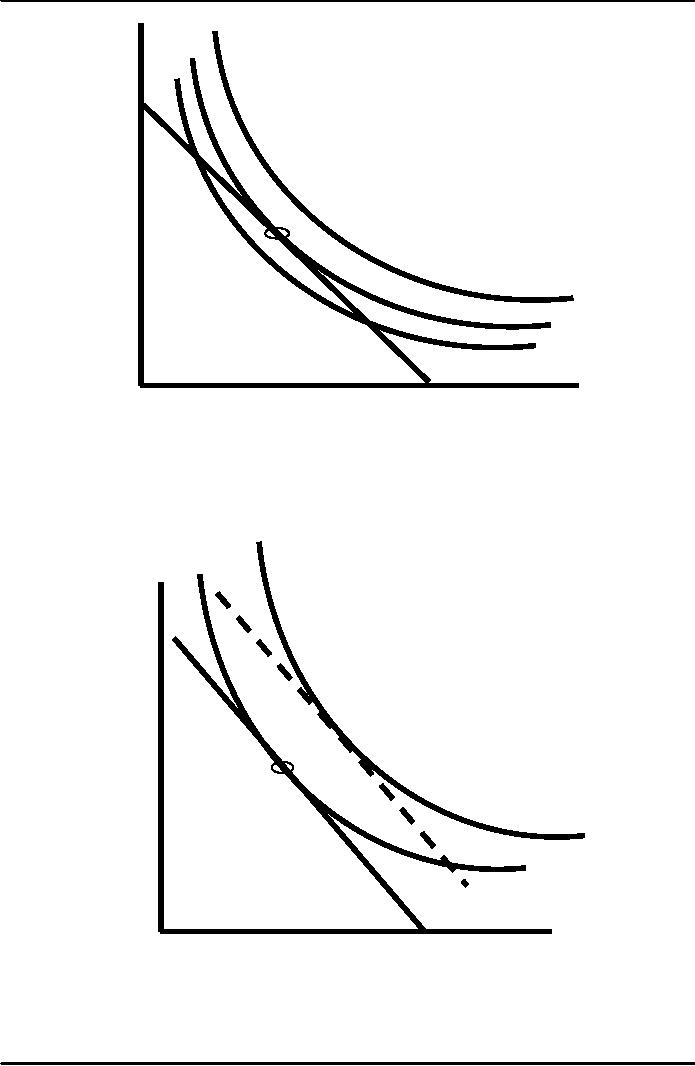

Optimization

The

consumer achieves his

highest (or optimal) level

of satisfaction by choosing the

point on

the

budget constraint that is on

the highest indifference

curve. At the optimum, the

indifference

curve

is tangent to the budget

constraint.

179

Macroeconomics

ECO 403

VU

Second-period

consumption

O

IC3

IC2

IC1

First-period

consumption

How

changes in income affect

consumption

An

increase in either first- or

second-period income shifts

the budget constraint

outward. If

consumption

in period one and

consumption in period two

are both normal

goods-

those

that

are

demanded more as income

rises, this increase in

income raises consumption in

both

periods.

Second-period

consumption

(1+r)Y1 +

Y2

O

IC2

IC1

First-period

consumption

Y1 +

Y2/(1+r)

180

Macroeconomics

ECO 403

VU

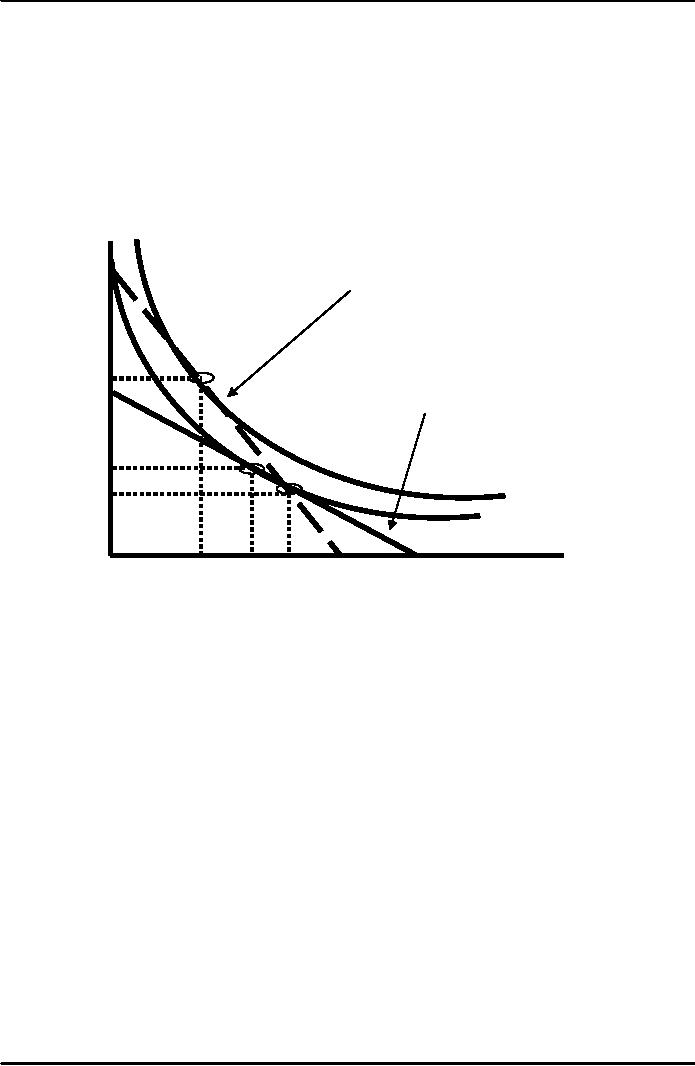

How

changes in real interest

rate affect

consumption

�

Economists

decompose the impact of an

increase in the real

interest rate on

consumption

into two effects: an

income

effect and a

substitution

effect.

�

The

income effect is the change

in consumption that results

from the movement to

a

higher

indifference curve.

�

The

substitution effect is the

change in consumption that

results from the change in

the

relative

price of consumption in the

two periods.

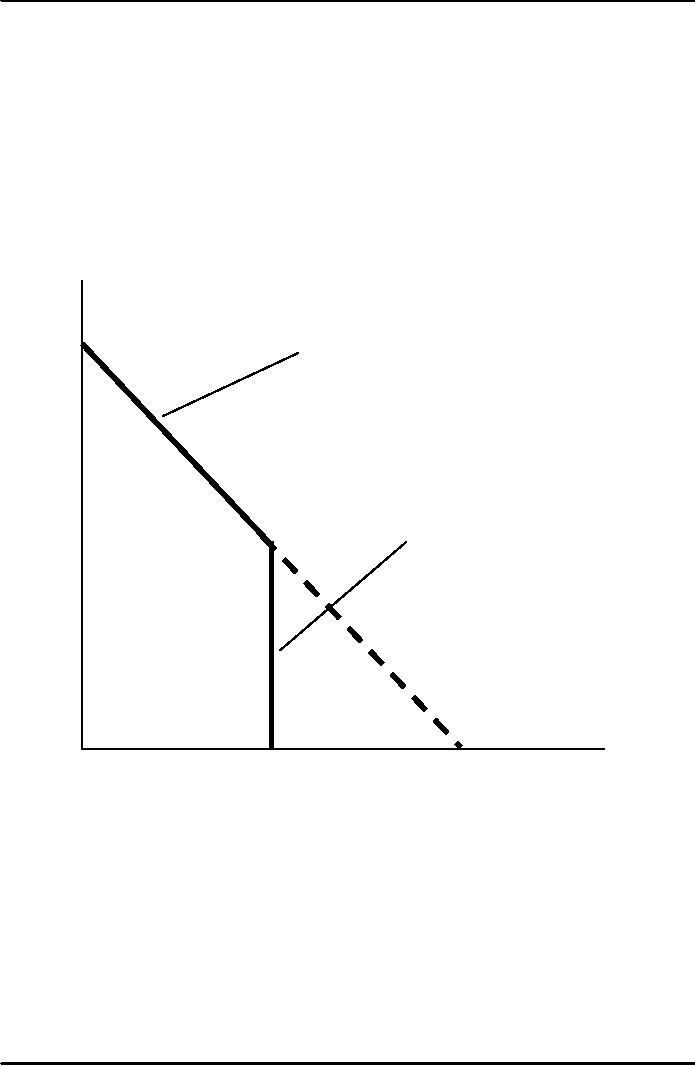

Second-

period

consumption

(1+r)Y1 +

Y2

New

budget

constraint

B

Old

budget constraint

A

C

Y2

IC2

IC1

Y1

Y1 +

Y2/(1+r)

First-period

consumption

An

increase in the interest

rate rotates the budget

constraint around the point

C, where C is

(Y1,

Y2).

The

higher interest rate reduces

first period consumption

(move to point A) and raises

second-

period

consumption (move to point

B).

�

Irving

Fisher's Model shows that

depending on the consumer

preferences, changes in

real

interest

rate could either raise or

lower consumption.

�

So,

economic theory alone cannot

predict how interest rate

influences consumption.

Therefore

economists have studied the

empirics of interest rate

affecting the

consumption

and

saving.

Savings

and the Real Interest

Rate

�

Data

shows that there's no

apparent relationship between

the two variables.

Or,

savings

does not depend on interest

rate.

�

Economists

claim that income and

substitution effects of higher

interest rates

approximately

cancel each other.

Constraints

on Borrowings

�

The

inability to borrow prevents

current consumption from

exceeding current income.

A

constraint

on borrowing can therefore be

expressed as C1 ≤

Y1.

181

Macroeconomics

ECO 403

VU

�

This

inequality states that

consumption in period one

must be less than or equal

to income

in

period one. This additional

constraint on the consumer is

called a borrowing

constraint,

or

sometimes, a liquidity

constraint.

�

The

analysis of borrowing leads us to

conclude that there are

two consumption

functions.

For

some consumers, the

borrowing constraint is not

binding, and consumption in

both

periods

depends on the present value

of lifetime income.

�

For

other consumers, the

borrowing constraint binds.

Hence, for those consumers

who

would

like to borrow but cannot,

consumption depends only on

current income.

�

If

the consumer cannot borrow,

he faces the additional

constraint that 1st period

consumption

cannot exceed 1st period income.

2nd period consumption,

C2

Budget

Constraint

Borrowing

Constraint

1st period consumption,

C1

Y1

182

Macroeconomics

ECO 403

VU

a:

borrowing constraint is

b:

borrowing constraint is

not

binding

binding

2nd period

2nd period

consumption

consumption

,

C2

,

C2

E

D

1st period

1st period

Y1

Y1

consumption,

C1

consumption,

C1

High

Japanese Savings

Rate

�

Japan

has one of the world's

highest savings rate.

�

On

one hand, many economists

believe that this is a key

to the rapid growth

Japan

experienced

in the decades after World

War II, The Solow

growth model also shows

that

saving

rate is a primary determinant of a

country's steady state level

of income.

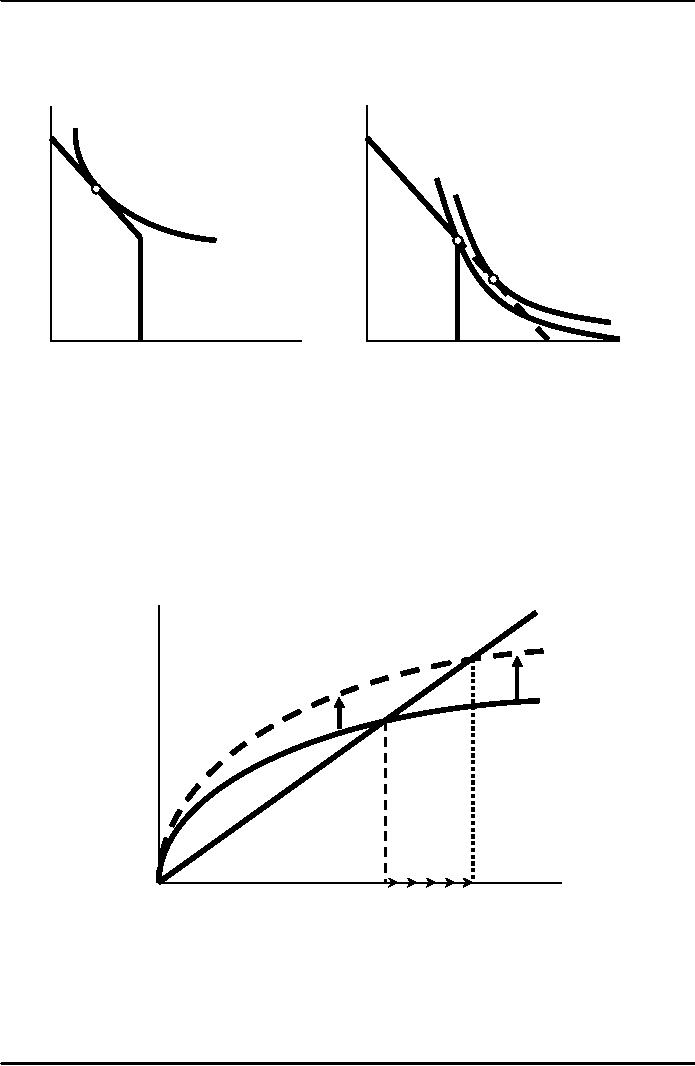

An

increase in the saving rate

raises investment causing

the capital stock to grow

toward a

new

steady state

Investment

δk

and

depreciation

s2 f(k)

s1 f(k)

k

k *

k *

2

1

�

On

the other hand, some

economists say that high

savings rate has contributed

to Japan's

slump

during 1990s.High savings

means lower consumption

which according to

IS-LM

model

translates into low

aggregate demand and reduced

income.

�

Why

Do Japanese consume so less or

save so much?

It is harder

for households to borrow in

Japan

183

Macroeconomics

ECO 403

VU

In case of

borrowing to purchase a house

(the most common cause of

borrowing), down

payment

rates are very high

(up to 40%)

Japanese Tax

system encourages saving by

taxing capital income very

lightly

Japanese

are more risk averse

and patient.

184

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION:COURSE DESCRIPTION, TEN PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS

- PRINCIPLE OF MACROECONOMICS:People Face Tradeoffs

- IMPORTANCE OF MACROECONOMICS:Interest rates and rental payments

- THE DATA OF MACROECONOMICS:Rules for computing GDP

- THE DATA OF MACROECONOMICS (Continued…):Components of Expenditures

- THE DATA OF MACROECONOMICS (Continued…):How to construct the CPI

- NATIONAL INCOME: WHERE IT COMES FROM AND WHERE IT GOES

- NATIONAL INCOME: WHERE IT COMES FROM AND WHERE IT GOES (Continued…)

- NATIONAL INCOME: WHERE IT COMES FROM AND WHERE IT GOES (Continued…)

- NATIONAL INCOME: WHERE IT COMES FROM AND WHERE IT GOES (Continued…)

- MONEY AND INFLATION:The Quantity Equation, Inflation and interest rates

- MONEY AND INFLATION (Continued…):Money demand and the nominal interest rate

- MONEY AND INFLATION (Continued…):Costs of expected inflation:

- MONEY AND INFLATION (Continued…):The Classical Dichotomy

- OPEN ECONOMY:Three experiments, The nominal exchange rate

- OPEN ECONOMY (Continued…):The Determinants of the Nominal Exchange Rate

- OPEN ECONOMY (Continued…):A first model of the natural rate

- ISSUES IN UNEMPLOYMENT:Public Policy and Job Search

- ECONOMIC GROWTH:THE SOLOW MODEL, Saving and investment

- ECONOMIC GROWTH (Continued…):The Steady State

- ECONOMIC GROWTH (Continued…):The Golden Rule Capital Stock

- ECONOMIC GROWTH (Continued…):The Golden Rule, Policies to promote growth

- ECONOMIC GROWTH (Continued…):Possible problems with industrial policy

- AGGREGATE DEMAND AND AGGREGATE SUPPLY:When prices are sticky

- AGGREGATE DEMAND AND AGGREGATE SUPPLY (Continued…):

- AGGREGATE DEMAND AND AGGREGATE SUPPLY (Continued…):

- AGGREGATE DEMAND AND AGGREGATE SUPPLY (Continued…)

- AGGREGATE DEMAND AND AGGREGATE SUPPLY (Continued…)

- AGGREGATE DEMAND AND AGGREGATE SUPPLY (Continued…)

- AGGREGATE DEMAND IN THE OPEN ECONOMY:Lessons about fiscal policy

- AGGREGATE DEMAND IN THE OPEN ECONOMY(Continued…):Fixed exchange rates

- AGGREGATE DEMAND IN THE OPEN ECONOMY (Continued…):Why income might not rise

- AGGREGATE SUPPLY:The sticky-price model

- AGGREGATE SUPPLY (Continued…):Deriving the Phillips Curve from SRAS

- GOVERNMENT DEBT:Permanent Debt, Floating Debt, Unfunded Debts

- GOVERNMENT DEBT (Continued…):Starting with too little capital,

- CONSUMPTION:Secular Stagnation and Simon Kuznets

- CONSUMPTION (Continued…):Consumer Preferences, Constraints on Borrowings

- CONSUMPTION (Continued…):The Life-cycle Consumption Function

- INVESTMENT:The Rental Price of Capital, The Cost of Capital

- INVESTMENT (Continued…):The Determinants of Investment

- INVESTMENT (Continued…):Financing Constraints, Residential Investment

- INVESTMENT (Continued…):Inventories and the Real Interest Rate

- MONEY:Money Supply, Fractional Reserve Banking,

- MONEY (Continued…):Three Instruments of Money Supply, Money Demand