|

PROBLEMS OF LOWER INCOME COUNTRIES:Poverty trap theories: |

| << AN INTRODUCTION TO INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND FINANCE |

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

UNIT

- 16

Lesson

16.1

PROBLEMS OF

LOWER INCOME

COUNTRIES

There

are huge income and

wealth disparities in the

world we live in. Roughly

one-fourth of the

world's

population accounts for on

three-fourths of the world's

resources and

consumption.

The

per capita income in the

world's poorest countries is

$330 per year whereas in

the richer

countries,

is $24,000 a year about 70

times higher!

More

worryingly, contrary to expectations

and wishes, these

disparities have not gone

away

since

the 1950s the time

when many of the world's

poorest countries (colonies)

got

independence.

In some cases (e.g. Africa),

disparities appear to have

actually increased,

widening

the living standards gap

between the first and

third worlds. Many people in

the Third

World

live in extreme poverty

beyond the wildest

imagination of the people

living in HICs.

Theories

about the Problems of

LICs:

In

order to explain this huge

problem of poverty and of

the asymmetric ownership of

wealth

and

income in the world,

economists have come up with

many theories.

Poverty

trap theories:

Poverty

trap theories explained the

relative poverty of the

Third World in the context

of the twin

gaps:

foreign exchange gap

(exports being less than

required imports) and an

underlying

savings

gap (domestic savings being

less than required

investment).11 As a result, the

LICs'

economies

were caught in the vicious

cycle of low saving, low

scale of investment,

low

productivity

gains (due to the absence of

scale economies), low per

capita growth

(remember

productivity

and technological progress

were the engines of PCI

growth), low savings

.......

The

Prebisch-Singer Hypothesis

(PSH):

A

rival theory was the

Prebisch-Singer Hypothesis (PSH),

which located the reasons

for this

persistent

poverty in the structure of

trade between the rich

and poor countries. The

PSH

maintained

that that LICs were

stuck in the production of

primary products (as

prescribed by

static

comparative advantage theories

like Hechscher-Ohlin prescribed)

which were subject to

both

volatility and declining

prices relative to manufactures

and capital goods.12

Some

economists pointed out the

lack of

human, social and public

capital in LICs as

the

single

most important factor

distinguishing them from,

say, post-WW2 Germany and

Japan,

countries

which were able to rebuild

themselves from total

destruction to great

economic

prosperity

on the back of a strong and

skilled workforce (human

capital), well-developed

institutions

like trust, meritocracy and

accountability (social capital),

and elaborate

communications,

energy and housing

infrastructures (public

capital).

Others

drew attention to the

very

fast rising populations in

LICs, and

the particular social

and

economic pressures created

thereby. Coupled also with

disease and severe ethnic

and

regional

conflicts, some saw the

situation in LICs as virtually

ungovernable.

Lack

of precious natural resources

(like oil, gold, gas,

iron, copper etc.) was

also cited by

some

as the reason for LICs'

continued poverty, and

examples were given of South

Africa and

the

OPEC countries, many of whom

were able to raise living

standards solely on the back

of

natural

resource exports. Strong

counter-argument exist against

this theory, for e.g.,

the LICs

which

registered the highest rates

of industrialization and GDP

growth during the last

four

decades,

namely: Korea, Taiwan, Hong

Kong, Singapore, did not

possess any

significant

natural

resources. The same is true

for Japan in the 20th century and the

European countries

in

the 18th and 19th

centuries.

11

Recall

from the discussion under

BOPs that M-X = I-S + G-T,

and thus, for a given

G-T, I-S and M-X go

hand

in

hand.

12

Refer

also to the micro lectures

on elasticity where the BOPs

problems of LICs are

explained in the context

of

income

price and substitution

elasticity's.

168

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

Development

Strategies:

Keeping

the reasons for persistent

poverty in LICs aside, there

are three broad

development

strategies

that have been adopted to

address the

situation.

I.

DEVELOPMENT THROUGH

TRADE

Up

till the 1970s, it was

thought that LICs needed to

develop their import

competing industries

(import-substituting

industrialization), reduce their

dependence on consumer goods

imports by

switching

to domestically produced goods,

and hence gradually attain

self-sufficiency and

foreign

exchange adequacy. Inspired by

dynamic comparative advantage

theories and the

massive

Soviet industrialization drive

launched under Stalin, this

model was

passionately

followed

by many South Asian, African

and Latin American

countries. The results were

not

very

positive, unfortunately. For

one, the nationalization

policies that often

accompanied the

pursuit

of the ISI model led to a

crowding out of private

entrepreneurship (and with

it, the spirit

of

competition), and the birth

of highly inefficient public

enterprises, which later

became a

breeding

ground for corruption,

nepotism and labour dumping

(excess hiring). Second,

the

huge

savings expected on imports

never quite materialized.

Given the large current

account

deficits

delivered by weak exports

and stubbornly high imports,

therefore, many of

these

countries

went into BOPs crises

after the 1970s.

The

East Asian Model:

A

rival trade model which

proved very successful was

the East Asian one.

These countries

(Korea,

Indonesia, Taiwan, Hong

Kong, Singapore, Malaysia,

and to a lesser extent

Thailand,

Indonesia

and The Philippines)

industrialized not to produce

for the local markets

(i.e. to

substitute

their imports) but to

produce for the

international market (competing

with foreign

producers).

As a result they had a

focus, from the very

start, on productive efficiency

and did

not

rely on high tariff

protection for very long

and therefore attained a

sustainable ascent on

the

comparative advantage ladder

(from primary products to

high tech goods). These

are the

countries

which have been the

fastest growing (or miracle)

economies of the last

quarter of the

20th century.

The

success of the

East Asian model,

notwithstanding, there is major

criticisms that

are

leveled

against richer countries

with respect to their double

standards on trade. The

criticism is

that,

while supporting free trade

internationally and whenever it

suits their interests, many

of

these

countries impose quotas,

tariffs, subsidies and

indirect restrictions (environmental

and

labour

standards etc.) to prevent

poor countries from selling

their primary products and

light

manufactures

to the rich country markets.

One example is the

agricultural sector, where

the

wealthy

west gives lavish subsidies

to its farmers, enabling the

latter to out-compete

LIC

farmers

who are not receiving

any subsidies form their

governments. One

argument,

therefore,

is to require rich countries to

open their markets to

exports from poor

countries.

II.

DEVELOPMENT THROUGH RESOURCE

TRANSFER

The

main idea here was

that (as mentioned earlier)

poor countries suffered from

savings and

foreign

exchange gaps that could

not be filled domestically,

and needed to be funded by

some

sort

of international resource transfer

from the rich countries

(former colonial powers

called

"donors")

to the poor countries (those

which got independence in

the mid-20th century).

Supporters

of the model were basically

those who felt that

the colonizing west needed

to take

responsibility

for the exploitation of the

colonized Third World. The

best way to do it was

to

give

aid: both grants (which

never had to be repaid) and

concessional loans (which

had to be

repaid

on very soft terms) to poor

countries to help them in

their initial years and to

facilitate

169

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

their

entry into the group of

prosperous nations.13 For

this reason, the UN charter

of 1948

prescribed

an annual 0.7% (of GNP)

contribution by all rich

countries to poor

countries.

However,

aid has not generally

been successful in lifting

former colonies out of

poverty. Living

standards

in many of the aid-receiving

countries have actually

fallen, indicating a clear

failure

of

aid. There are many

reasons why this could

have happened, but the

most important ones

are

perhaps the misuse of aid

proceeds by recipient country

governments through

misallocation,

embezzlement and corruption;

the negative role of donors

in forcing recipient

countries

to use aid proceeds for

importing the goods and

services from only the

donor

country;

the politicizing nature of

aid and its associated

conditionalities14;

aid fatigue on the

part

of donors (i.e. tiredness

resulting from having to

give aid year after

year without any

concrete

benefits), the inadequacy of

aid (the aid given

has never quite been

enough, and only

about

0.35% of rich country GNP

has been allocated as

development aid); the

crowding out of

domestic

savings (that is, as aid

comes into the country

the incentive for local

citizens to save

reduces,

thereby compounding the low

saving rate problem of poor

countries).

Official

aid is not the only

type of resource transfer.

There are private capital

flows (portfolio

investments

and bank lending) that

can also fill resource

gaps in LICs. However,

the

experience

with these has not

been successful either. The

debt crisis of the 1980s in

Latin

America,

Africa and Asia, and

the recent spate of

financial crises in Mexico,

East Asia, Russia,

Brazil

and Argentina have all

testify to the dangers of

modern day private capital

flows. Such

flows

are highly reversible and

often pro-cyclical accentuating

boom-bust cycles in

recipient

countries.

Due

to the failure of the above

alternative types of resource

flows, attention has, of

late, shifted

to

foreign direct investment

(FDI). This type of resource

transfer has been deemed

more

successful

than others due to its

ability to relieve three

constraints simultaneously: the

foreign

exchange

and savings constraints

(mentioned earlier), the

skills constraint (the fact

that LICs

do

not have the skills

managerial or technical for

industrial upgrading and

export market

tapping).

FDI had been unwelcome in

many LICs in the 1950s

and 60s as it was seen as

a

continuation

of colonialism. Foreign money

coming into one's country

was one thing,

foreign

firms

coming, operating and taking

control quite another!

Indeed there was the

perceived risk

that

foreign firms would take

over the strategic sectors

of society financial

services,

communications

and power. Over time,

LICs' aversion to FDI has

decreased considerably.

Many

now recognize the benefits

of irreversible FDI and its

skill-transfer related

advantages

for

countries lacking in stability

and human capital,

respectively. Indeed, countries

which have

relied

on FDI more than debt

and portfolio investments to

integrate into the global

economy

(China,

Chile and many of the

East Asian tigers), have

been the most successful

development

examples

of the last 25 years.

OPTIONAL:

For

a detailed review of the

alternative forms of resource

transfer and their

relative

merits, please see International

Resource Transfer.ppt

III.

DEVELOPMENT THROUGH STABILISATION AND

REFORM

The

reasoning here was that

trade and resource transfer

could not, by themselves,

lift LICs out

of

poverty. Unless LICs'

macroeconomic imbalances (high

inflation, current account

deficits

etc.)

were removed (stabilization),

and the structural

impediments to their growth

relieved

(structural

reform), trade and resource

transfer could not translate

into long-term

improvement

in

living standards. This

became particularly obvious

after the 1980s debt

crisis that swept

across

Latin America, Africa and

Asia. It is at this point in

time that the two

international

financial

institutions (IFIs) the

International Monetary Fund

(IMF) and the World

Bank (WB)

became

involved in macroeconomic stabilization

and structural reform,

respectively.

13

An

early example of the success

of aid was post-World War II

Germany, which received a

lot of financial

assistance

from the U.S. (Marshall

Plan) and managed to become

an economic giant inside 2

decades after the

end

of

the war. It was hoped

that by giving aid to other

poor countries, the same

result would obtain.

14

These

conditionalities are often perceived as

an infringement of the freedom of the

recipient country, making the

pursuit

of donor-prescribed

policies

politically unviable.

170

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

Importantly,

the countries in which the

IFIs got involved, did

not have much bargaining

power

vis-�-vis

the IFIs, because the

latter had bailed out

these countries (by offering

them soft

multilateral

loans) out after their

debt defaults. As a result,

the IFIs were able to

determine the

pace

and direction of macroeconomic

policy reform in these

countries. For a summary of

the

origins

of the IMF and the World

Bank and their structure

and ownership, please see

IFIs.ppt.

Most

of the IMF's stabilisation

policies (and

indeed WB's reform ones)

were derived from

neo-classical

economics, known since 1990

as the "Washington Consensus".

IMF's main

stated

objective was to ensure both

through internal balance

(supply=demand, i.e.

low

inflation,

full employment) and

external balance (sustainable

BOP and external debt

position).

The

approach was "stabilization"

through "demand" management,

the three tools of the

latter

being:

�

Tight

monetary policy: "demand

reducing"; expected to work

via higher interest

rates

which

reduced private sector

consumption and investment

demand, suppressed

inflation

and boosted domestic

savings. High interest rates

also caused higher

capital

inflows

(lower capital flight) and

helped restore external

balance via the

capital

account.

�

Tight

fiscal policy: also

"demand reducing"; worked

via higher revenues

(increased

taxation

and broader tax base)

and reduced expenditure on

subsidies, public

sector

corporations

etc. There was also

reduced demand (including,

for imports) and

government's

borrowing requirement (boosted

the creditworthiness of the

government

as

a borrower making borrowing

cheaper).

�

Devaluation:

produced

"demand switching" from

imports to home produced

tradable

goods.

Worked via increased

competitiveness, export diversification,

reduced need for

export

subsidies (as exporters

became competitive), and

increased investor

confidence

in

the local currency

(preventing dollarisation by people

fearing an impending

devaluation).

LICs'

experience with IMF policies

has generally not been

successful: The above

policies have

drawn

heavy & wide-ranging criticism.

Critics have drawn attention

towards

�

Short-term

policy conflicts: demand

management policies compromise

internal

balance

esp. income & employment;

lower government expenditure

means less

output,

jobs. Higher interest rates

can lead to corporate

bankruptcies, bad debts

and

financial

sector crises.

�

Devaluation

can

raise prices of imports,

including necessities, raw

materials and

investment

goods. Also, devaluation

translates into inflation

when there is real

wage

resistance;

i.e. when a devaluation-induced

rise in import prices feeds

fully into the

domestic

price level through

wages.

�

Demand-reduction

policies are

anti-growth: increased taxation

can stifle the

productive

sector, as widening the tax

net proves difficult and

most of the burden

falls

on

a few taxpayers; cutting

government expenditure can

cause reduced public

investment

in infrastructure, education and

health; higher interest

rates can discourage

private

investment.

�

Stabilisation

hurts the poor: expenditure

cuts almost always fall

partly on the social

sectors

most relevant to the poor

(health, education, food/fertilizer

subsidies etc.). This

can

lead to political instability,

jeopardize economic stabilization

and delay or reverse

"reform".

Esp. difficult for

democratic governments to push

the harsh

stabilization

measures

through.

It

is now recognized that these

policy conflicts need to be

integrated into the

Programme in

advance

through the institution of

proper safety nets for

the poor, and assurances

that all

"IMF-induced"

aid (or debt relief) is

channeled strictly to poverty

reduction programmes.

World

Bank's structural reform

policies:

The

World Bank's structural

reform policies have usually

involved the

following:

171

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

�

Liberalization

of prices, removal of

subsidies

�

Deregulation

involving dismantling of licensing

systems and red-tape

�

Privatization

of state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

SOEs were usually

considered

inefficient

due to political interference,

and a lack of competition,

cost awareness and

fear

of bankruptcy

�

Trade

liberalization, including tariffication

of non-tariff-barriers, harmonization of

tariffs

and

an eventual reduction

thereof

�

FDI

liberalization, to create a transparent,

predictable environment for

foreign investors

to

operate in

�

Financial

liberalization, involving ending of

financial repression policies

(artificially low

interest

rates, credit rationing,

restrictions on banking competition)

and government

involvement

in investment allocation

�

Capital

account liberalization, i.e.

removing controls on capital

flows

�

Governance

and administrative

reforms: reducing waste

in, and

improving

reliability/quality

of, pubic services;

strengthening tax

administration; fiscal

decentralization;

elimination of corruption; enhancing

predictability of legal

and

regulatory

framework; reducing over-employment in

public sector

While

most of the policies

prescribed by the World Bank

appeared desirable, some of

them

came

with conditionalities that

were perceived as politically

sensitive, "patronizing",

and

involving

dismantling of strong entrenched

interest (like domestic

industrialists). Predictably,

therefore,

non-compliance was a major

feature of such

programmes.

Even

in cases where the domestic

government intended to implement

the prescribed

reforms,

compliance

problems occurred due to

poor sequencing and/or bad

timing. Example 1:

relaxing

capital

controls given a poorly

regulated domestic financial

system exposed countries

to

increased

risk of financial crisis.

Examples 2: Trade liberalization

(reducing tariffs) or

financial

liberalization

(raising interest rates)

before achieving fiscal

consolidation (i.e. rationalization

of

government

expenditures and widening of

tax base), caused borrowing

costs to balloon and

fiscal

deficits to widen (Zambia,

Zimbabwe, Pakistan).

Insistence

on rapid liberalization of all

sectors has over-stretched

many LICs'

institutional

capacities.

So

what are the proposed

solutions?

�

Some

Left-leaning critics totally

reject the globalization

doctrine and want the

free-

market

model dumped in favour of a

more interventionist set-up.

Japan and East

Asia

are

presented as examples of countries

which witnessed tremendous

growth despite

having

serious market-unfriendly "distortions"

in their economies. The

argument these

critics

present is that, in a second-best

world, certain distortions

may be desirable.

�

Many

NGOs, and LICs themselves,

argue for the reform of

the global trading system

to

open

up rich country markets and

address commodity price

instability.

�

Right-leaning

groups (including the US

Treasury and the Republican

Party) which wish

to

see the withdrawal of the

IMF from development finance in

favour of the World

Bank;

they

would like to see the IMF

focusing only on crisis-prevention

and providing short-

term

liquidity to countries facing

BOPs problems. Many NGOs

agree that IMF's

development

finance policies have failed

but are unclear on whether

or not the IMF

should

totally withdraw. They fear

that in the absence of

alternatives (like grants

etc.),

overall

aid to LICs may

fall.

�

The IMF

and World Bank themselves

want to improve the quality

of conditionalities

while

reducing their quantity,

encourage government participation in

policy design and

the

setting of these conditionalities so as

to encourage ownership of the

Fund and

Bank

programmes.

�

NGOs

and rich country government,

of late, have stressed the

need to integrate

poverty

reduction objectives and

sustainable development into

IMF/World Bank

172

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

programmes:

Poverty Reduction Strategy

Papers have been written in

this context to

ensure

sustainable development with a

human face.

�

Rich

country governments also

emphasize the importance of

good governance in

public

policy, better management of

public resources, greater

transparency, active

public

scrutiny, and generally

increased government accountability in

fiscal

management.

173

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

END

OF UNIT 16 EXERCISES

The

Human Development Index is a

measure of well-being that is

based on three

equally

weighted

indexes: per capita GDP,

educational attainment and

life expectancy. Dr

Mahboob-ul-Haque

(who also served as

Pakistan's Foreign Minister in

the 1980s) was

the

main

force behind this idea.

For what reasons are

HDI and per-capita GDP

rankings likely

to

diverge?

When

the other two elements of

HDI educational attainment

and like expectancy

diverge

from

per capita income in the

rank order. One of the

main reasons for this

divergence is

inequality.

Thus a country with a high

GDP per capita, but

which is very unequally

distributed,

may

have a large proportion of

the population which is

poor, with relatively little

access to

education

and with a relatively low

life expectancy. This is the

reason why countries like

Qatar

and

Saudi Arabia despite being

very high on the per

cpaital GDP ranking, appear

quite low on

the

HDI ranking list.

If

a disastrous harvest of rice

were confined to a particular

country, would (a) the

world

price

and (b) its own

domestic price of rice

fluctuate significantly? What

would happen

to

the country's export

earnings and the earnings of

individual farmers?

a)

The world price would

not rise significantly as a

result of its poor harvest.

In the extreme

case

of a small country facing a

perfectly elastic demand for

its rice exports, the

world

price

would be unaffected by its

bad harvest.

b)

If rice were a significant

proportion of its total

exports, the fall in rice

production, and

hence

sales, would cause the

current account to deteriorate

and the exchange rate

to

depreciate

(assuming a flexible exchange

rate). This would

increase the domestic

currency

price of its rice

exports.

The

country's foreign exchange

earnings would fall.

Individual farmers' earnings

would also fall,

unless,

the rise in price from

the exchange rate

depreciation were sufficient to

offset the fall in

output

and sales (which is

unlikely, unless rice

exports constitute a major

portion of total

exports).

Why

is an overvalued exchange rate

likely to encourage the use

of capital-intensive

technology?

Because

it reduces the price of

imported capital equipment

(assuming that such

equipment has

low

or zero tariffs imposed on

it).

Would

the use of import controls

(tairffs or quotas) help or

hinder a policy of

export-

orientated

industrialisation?

In

the early stages of

industrialisation they may

help a country build up its

infant industries

industries

that later could become

export orientated. If protection is

maintained for too long, or

is

too

distorting, however, such

industries could well remain

inefficient and find it

difficult to

compete

internationally.

Will

the adoption of labour-intensive

techniques necessarily lead to a

more equal

distribution

of income?

Not

if the amount of investment

varies significantly from

one sector of the economy to

another. If

it

did, then those working in

sectors with new efficient

labour-intensive technology would

gain,

while

the poor, the dispossessed,

and those working in old

inefficient industries would

not.

Income

distribution could become

less equal.

Consider

the arguments from the

perspective of an advanced country

for and against

protecting

its industries from imports

of manufactures from lower-income

countries.

174

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

Consumers

will lose from such

protection, because they

will be denied access to

lower-income

countries'

products at such low prices.

Workers and employers in the

industries threatened by

cheaper

imports from lower-income

countries will gain from

the protection. Nevertheless

there

will

be a net welfare loss to the

country. A better solution to

the problem of those in

the

industries

threatened by the imports

might for the government to

help in the redeployment

of

labour.

What

is the difference between

mechanical efficiency and

economic efficiency?

Mechanical

efficiency is where there is a

low energy loss from a

machine. For example, if

a

machine

has an 80 per cent

mechanical efficiency, this

means for every 100

units of energy

used

to power the machine, it

produces 80 units of energy

output. In the context of

the internal

efficiency

of a firm, economic efficiency

involves producing a given

output with the least

costly

combination

of factors.

Why

may governments of lower income

countries be less strict

than developed

countries

in

controlling pollution?

Reasons

include:

a.

Given the much lower

average levels of income,

there is a higher level of

marginal utility

from

increased output relative to

the marginal pollution

costs.

b.

There is often less

political pressure on governments to

reduce pollution.

c.

Possible greater ignorance of

the full extent of the

harmful effects of the

pollution.

What

difficulties is a government likely to

encounter in encouraging the

use of labour-

intensive

technology?

Difficulties

include:

a.

Bias of firms towards using

capital-intensive technologies which

they see as `modern'.

b.

Lack of efficient labour-intensive

techniques available (due to a

lack of research and

development).

c.

Multinationals' preference for

using techniques with which

they are familiar.

Such

techniques,

having been developed in

advanced countries, are

likely to be capital

intensive.

d.

Labour-intensive technology may

require a higher level of

skills from the

operatives.

What

would be the effect on the

levels of migration and

urban unemployment of

the

creation

of jobs in the

towns?

Urban

employment would rise with

the additional jobs. But if

each job created in the

towns

encourages

more than one person to

migrate from the

countryside, the level of

urban

unemployment

will also increase.

Is

there any potential conflict

between the goals of

maximising economic growth

and

maximising

either (a) the level of

employment or (b) the rate

of growth of employment?

a)

Maximising growth may

involve using more

capital-intensive techniques, because

they

create

a greater surplus for

reinvestment. But the

adoption of more

capital-intensive

techniques

will reduce the level of

employment.

b)

There is less likely to be a

conflict here. If capital-intensive

techniques lead to a

faster

growth

in output, they will tend to

lead to a faster growth in

employment, albeit from

a

lower

level. (This conclusion will

not follow, however, if

there is a continuous switching

to

more

capital-intensive techniques as profits

are reinvested.)

175

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

What

is the relationship between

unemployment and (a)

poverty; (b)

inequality?

a)

The greater the

unemployment, the greater

will tend to be the level of

poverty, given that

in

most lower-income countries

there is little or no state

financial support for

the

unemployed.

b)

The greater the

unemployment, the greater

will tend to be the level of

inequality. Society

will

become increasingly polarised

into those with and

those without jobs.

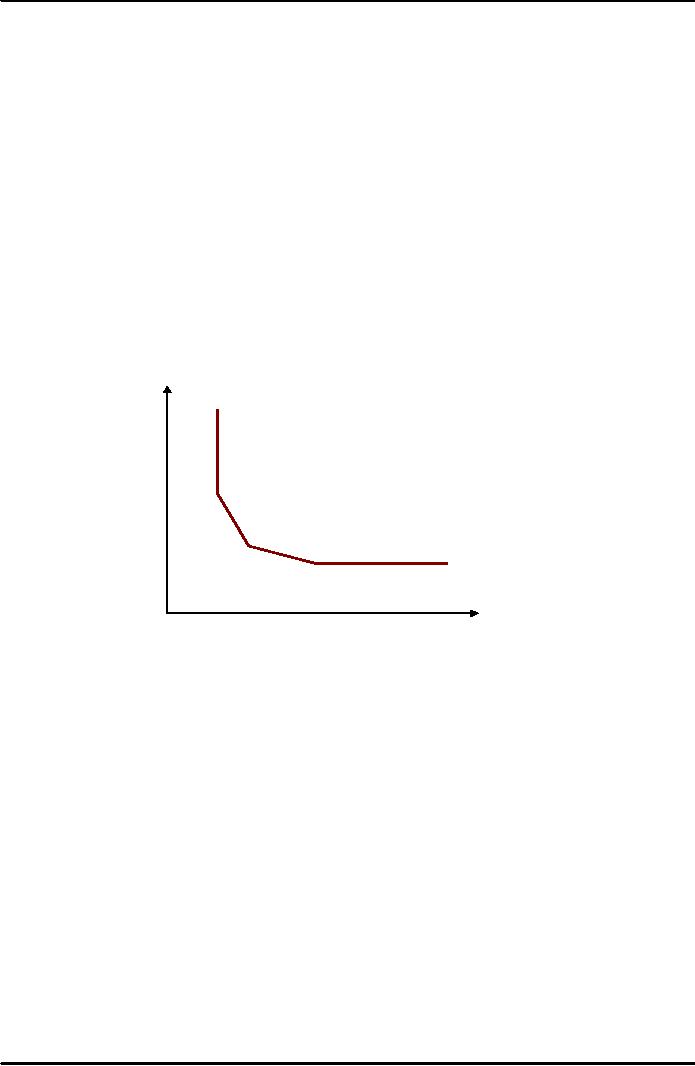

If

there were three techniques

available, what would the

isoquant look like? Would

it

make

any difference to the

conclusions of this

model?

The

isoquant would have four

straight-line sections. One

vertical; then two

downward-sloping

sections,

the higher one steeper

than the other; then a

horizontal section. This is

illustrated in

the

diagram opposite. Each of

the three `corners' of the

isoquant would be at the

capital/labour

ratio

of one of the three

techniques.

An

isoquant like this would

make no difference to the

conclusions of the model. A

capital-

intensity

bias could still lead to a

more capital-intensive technique

being chosen from the

three

available,

than that warranted by

questions of cost

alone.

K

L

If

more jobs were created in

the towns, how, in the

ruralurban migration model,

would

this

affect (a) the level of

urban unemployment; (b) the

rate of urban

unemployment?

If

more jobs were created in

the towns, Lm would

rise. This would cause

Wue to rise.

a)

If Wue rises, more people

will migrate and thus

the level of urban

unemployment will

rise.

b)

If the urban wage (Wu),

the rural wage (Wr)

and the cost of migration

(α) are

unaltered,

then

migration will take place

until Wu.Lm/Lu has

returned to its original

level, with Lm/Lu

the

same as before. Thus

although the level of

unemployment has risen, the

rate of

unemployment

has stayed the

same.

What

common ground is there

between structuralist and

monetarist explanations of

inflation

and lack of growth in

lower-income countries?

Structuralist

economists generally accept

that high inflation is

accompanied by high rates

of

growth

in the money supply, even

though they see monetary

growth as a symptom of

the

problem

rather than its basic

cause.

Both

structuralists and monetarists

accept the importance of

supply-side policies to

relieve

bottlenecks,

increase growth and reduce

unemployment. Monetarists, however,

generally see

the

means of achieving this to be a

liberating of market forces,

whereas structuralists

generally

advocate

interventionist policies.

176

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

One

solution proposed to help

solve Argentina's weak

financial position is that it

should

abandon

the peso as its unit of

currency and replace it with

the US dollar (i.e.

"dollarise").

What

advantages and drawbacks

might such a solution have

for the Argentine

economy

both

in the short and the

long term?

The

advantages are that there

would be much greater

currency stability and a

more stable

macroeconomic

environment, with inflation

more under control. In the

short-term this would

help

to

restore confidence in the

economy and encourage people

to save. In the longer term

it would

encourage

inward investment and trade.

The disadvantage is that

interest rates would

be

determined

in the USA, and they

might not be suitable for

the Argentine economy at any

given

time:

in other words, Argentina

would lose control over

monetary policy. The

arguments here are

similar

to those concerning whether

the UK should adopt the

euro. The main difference is

that

the

UK would have considerable

input into eurozone

macroeconomic policy, whereas

Argentina

would

have no input into US

macroeconomic policy.

What

are the relative advantages

and disadvantages to a lower-income

country of

rescheduling

its debts compared with

simply defaulting on them

(either temporarily or

permanently)?

Default

is a high-risk strategy. The

benefits are an immediate

wiping out of debt. The

potential

costs

are great, however. Its

assets in foreign institutions

may be confiscated, as too

may its

ships

and merchandise in transit.

Once having defaulted, it

will be virtually impossible to

raise

future

loans to rebuild the

economy. The threat of

default, however, especially if

made by

several

debtor countries acting

together, could force

creditor institutions to offer

lower interest

rates

or more generous rescheduling

programmes, or even to write

off a certain portion of

the

debt.

If

reductions in lower-income countries'

debt are in the

environmental interests of

the

whole

world, then why have

developed countries not gone

much further in reducing

or

cancelling

the debts owed to

them?

Because

it would not be in the

private interests of the

banks concerned. Even in the

case of

official

government loans, individual

developed countries may be

reluctant to cancel debts

on

their

own, feeling that it is not

their specific

responsibility.

Would

it be possible to devise a scheme of

debt repayments that would

both be

acceptable

to debtor and creditor

countries and not damage

the environment?

A

longer period to pay would

reduce the pressure on

lower-income countries to exploit

their

environment.

Also direct financial help

to lower-income countries to protect

the environment

would

be in the global interest

and could also help to

reduce lower-income countries'

debt

burden.

Would

the objections of lower-income

countries to debt-equity swaps be

largely

overcome

if foreign ownership was

restricted to less than 50

per cent in any company?

If

such

restrictions were imposed,

would this be likely to

affect the `price' at which

debt

were

swapped for

equity?

To

some extent, yes.

Lower-income countries would be

able to retain the

controlling interest in

their

companies within their

borders. There would still

be foreign influence in the

running of the

companies,

however, but this may

not be wholly unwelcome with

the expertise that

advanced

countries

can bring.

Restricting

ownership to less than 50

per cent would reduce

the benefits to the

developed-

country

banks or companies. They

would therefore be unwilling to

pay such a high price

for

equity

than if they had been

able to acquire a controlling

share.

177

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

Imagine

that you are an ambassador

of a lower-income country at an

international

conference.

What would you try to

persuade the rich countries

to do in order to help

you

and

other poor countries

overcome the debt problem?

How would you set

about

persuading

them that it was in their

own interests to help

you?

You

could try to persuade them

to reschedule your debts and

to grant new loans on

more

concessionary

terms. This would be in

their interests if it enabled

you to give a firmer

guarantee

that

the loans would be

repaid.

You

might also try to encourage

them to sign trade deals

with you or companies in

your country,

in

order to improve your

balance of payments. This

would again be in their

interests in that it

would

enable you more easily to

service any loans they

had made to you.

You

might also try to persuade

them to reduce interest

rates, both to make it

easier for your

country

to service its debts, and to

give a boost to world demand

and hence to the demand

for

your

exports. You could try to

show them that a growing

world economy was in

everyone's

interests.

To

what extent can

international negotiations over

economic policy be seen as a

game of

strategy?

Are there any parallels

between the behaviour of

countries and the

behaviour

of

oligopolists?

There

is a collective gain to countries

from agreement over

harmonisation and the

greater

international

macroeconomic stability that

would result. Each

individual country,

nevertheless,

would

have to agree to take

decisions which might be

directly against its

short-term national

interests.

Each country may therefore

be tempted to break the

agreement.

Clearly

there is a parallel with

oligopoly. Collusion is in the

collective interests of oligopolists,

but

each

will be tempted to

cheat.

The

greater the number of

countries/oligopolists in an agreement,

and the more divergent

their

individual

economic circumstances, the

greater the likelihood of

one country/oligopoly

breaking

the

agreement, and the less

the commitment, therefore, of

countries/oligopolists in general to

the

agreemen

------------------THE

END-----------------

178

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO ECONOMICS:Economic Systems

- INTRODUCTION TO ECONOMICS (CONTINUED………):Opportunity Cost

- DEMAND, SUPPLY AND EQUILIBRIUM:Goods Market and Factors Market

- DEMAND, SUPPLY AND EQUILIBRIUM (CONTINUED……..)

- DEMAND, SUPPLY AND EQUILIBRIUM (CONTINUED……..):Equilibrium

- ELASTICITIES:Price Elasticity of Demand, Point Elasticity, Arc Elasticity

- ELASTICITIES (CONTINUED………….):Total revenue and Elasticity

- ELASTICITIES (CONTINUED………….):Short Run and Long Run, Incidence of Taxation

- BACKGROUND TO DEMAND/CONSUMPTION:CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

- BACKGROUND TO DEMAND/CONSUMPTION (CONTINUED…………….)

- BACKGROUND TO DEMAND/CONSUMPTION (CONTINUED…………….)The Indifference Curve Approach

- BACKGROUND TO DEMAND/CONSUMPTION (CONTINUED…………….):Normal Goods and Giffen Good

- BACKGROUND TO SUPPLY/COSTS:PRODUCTIVE THEORY

- BACKGROUND TO SUPPLY/COSTS (CONTINUED…………..):The Scale of Production

- BACKGROUND TO SUPPLY/COSTS (CONTINUED…………..):Isoquant

- BACKGROUND TO SUPPLY/COSTS (CONTINUED…………..):COSTS

- BACKGROUND TO SUPPLY/COSTS (CONTINUED…………..):REVENUES

- BACKGROUND TO SUPPLY/COSTS (CONTINUED…………..):PROFIT MAXIMISATION

- MARKET STRUCTURES:PERFECT COMPETITION, Allocative efficiency

- MARKET STRUCTURES (CONTINUED………..):MONOPOLY

- MARKET STRUCTURES (CONTINUED………..):PRICE DISCRIMINATION

- MARKET STRUCTURES (CONTINUED………..):OLIGOPOLY

- SELECTED ISSUES IN MICROECONOMICS:WELFARE ECONOMICS

- SELECTED ISSUES IN MICROECONOMICS (CONTINUED……………)

- INTRODUCTION TO MACROECONOMICS:Price Level and its Effects:

- INTRODUCTION TO MACROECONOMICS (CONTINUED………..)

- INTRODUCTION TO MACROECONOMICS (CONTINUED………..):The Monetarist School

- THE USE OF MACROECONOMIC DATA, AND THE DEFINITION AND ACCOUNTING OF NATIONAL INCOME

- THE USE OF MACROECONOMIC DATA, AND THE DEFINITION AND ACCOUNTING OF NATIONAL INCOME (CONTINUED……………..)

- MACROECONOMIC EQUILIBRIUM & VARIABLES; THE DETERMINATION OF EQUILIBRIUM INCOME

- MACROECONOMIC EQUILIBRIUM & VARIABLES; THE DETERMINATION OF EQUILIBRIUM INCOME (CONTINUED………..)

- MACROECONOMIC EQUILIBRIUM & VARIABLES; THE DETERMINATION OF EQUILIBRIUM INCOME (CONTINUED………..):The Accelerator

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS (CONTINUED…….)

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS (CONTINUED…….):Causes of Inflation

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS (CONTINUED…….):BALANCE OF PAYMENTS

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS (CONTINUED…….):GROWTH

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS (CONTINUED…….):Land

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS (CONTINUED…….):Growth-inflation

- FISCAL POLICY AND TAXATION:Budget Deficit, Budget Surplus and Balanced Budget

- MONEY, CENTRAL BANKING AND MONETARY POLICY

- MONEY, CENTRAL BANKING AND MONETARY POLICY (CONTINUED…….)

- JOINT EQUILIBRIUM IN THE MONEY AND GOODS MARKETS: THE IS-LM FRAMEWORK

- AN INTRODUCTION TO INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND FINANCE

- PROBLEMS OF LOWER INCOME COUNTRIES:Poverty trap theories: