|

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

Lesson

10.3

MACROECONOMIC

EQUILIBRIUM & VARIABLES; THE

DETERMINATION OF

EQUILIBRIUM

INCOME (CONTINUED...........)

THE

KEYNESIAN MULTIPLIER AND

ACCELERATOR

The

Keynesian Multiplier:

Reverting

to the 450 line

approach, the term

[1/(1-b)]

is

called the Keynesian

multiplier ("k")

and

is the factor by which

equilibrium output, income or

expenditure increase in response

to

an

increase in AD (caused by an increase in

"a", G, I or X-M). The

higher is b, the bigger is

the

multiplier.

Mathematical

representation of Keynes multiplier is as

follows:

Y

= C + I + G + NX

As

C

= a + bY

Then,

Y

= a + bY + I + G + NX

Y

bY = a + I + G + NX

Y

= a + I + G + NX = 1 (a + I + G + NX)

1b

1b

k=

1____

1b

Keynes's

intuition about the

multiplier was as follows:

An

increase in AD caused by an injection

into the circular flow,

e.g. higher

government

spending

on wages paid to government

employees, would lead to

higher money wages

held

by

government servants. Higher

wages would translate into

higher consumption

expenditure

on

goods and services in the

economy, leading to higher

money incomes of sellers of

goods

and

services. When firms see

consumers more prosperous,

they are incentivised to

produce

more,

thus their demand for

labour goes up. This

triggers a second rise of

income increases in

the

hands of workers (who are

also consumers) leading to a

further multiplied effect

on

consumption,

production and hiring. And so

on. The multiplier effect

would not be infinite

as

there

are leakages (saving, taxes,

imports) from the circular

flow of incomes each time

the

workers

receive wages from firms.

The lower the leakages

and the higher the

marginal

propensity

to consume, the higher will

be the multiplier

effect.

Keynes

paradox of Thrift:

The

reverse multiplier effect

can be illustrated in the

context of Keynes's paradox of

thrift,

which

highlights the negative

impact of higher saving in an

economy in recession. As

noted

earlier,

Classical economists thought

the solution to the problem

of low investment during

the

Great

Depression was high real

interest rates caused by low

savings. If the latter could

be

increased,

the real interest rate

would fall and investment

would pick up. However,

Keynes

said

that such thrift (or

conservative saving behaviour)

would accentuate the

recession. As

people

save more, they will

spend less. Firms will

therefore produce less, and

labour hiring

will,

as a result, fall, leading to a

decline in incomes. This

decline would also happen in

a

multiplied

fashion, causing a huge

decline in national income.

The paradox lies in the

fact that

that

saving, while usually

considered good for any

one individual, can actually

be harmful to

the

overall economy if everyone

started saving.

The

Accelerator:

The

accelerator is a related concept

which formalizes the

investment response to output

or

income

changes in an economy. The

key observation here is that

when an economy begins

to

recover

from a slump, investment can

rise very rapidly and, in

percentage terms, the rise

in

investment

may be several times the

rise in income. Since

investment is an injection into

the

100

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

circular

flow of income, these

changes in investment will

cause multiplied changes in

income

and

thus heighten a boom or

deepen a recession. The

formula for the accelerator

is α

=

I/(ΔY),

or

(ΔK)/(ΔY),

noting that I = ΔK, where I is

investment and K is capital

(the stock of plants,

buildings

or machinery in the

economy).

The

reason why investment increases by

much more than a change in

income is as

follows:

Suppose

firms anticipate national

income (and hence the

demand for their products)

to rise by

10%

p.a. over the next 5

years. In response, firms

will therefore normally look

to undertake an

investment

(such as buying a machine)

which will enable them to

meet this new demand

for

the

entire 5 year period. It is

usually neither feasible nor

possible to buy a machine

that has a

one

year life! Thus, it is easy

to see why a given annual

change in output (10%) might

prompt

firms

with a five year horizon to

make an investment of over

50%.

Reverting

back to the formula, the

size of the accelerator, α,

depends on the marginal

capital

to

output ratio: (ΔK)/(ΔY).

This is the cost of extra

capital required to produce a

Re.1 increase

in

national output. So if Rs.2

billion worth of capital is

required to produce Rs.1

billion worth of

output,

then (ΔK)/(ΔY)

is 2. It is easy to see that,

other things being equal

the marginal capital-

output

ratio and the accelerator

are essentially the same.

α

is

likely to be greater than

1.

Interaction

of accelerator and

Multiplier:

It

is obvious that the

interaction of the accelerator

and multiplier can set

off a chain reaction

in

the

economy which can life

output and income manifold.

For e.g., if there is a rise

in

government

expenditure, this will lead

to a multiplied rise in national

income. But this rise

in

national

income will set off an

accelerator effect: firms

will respond to the rise in

incomes (and

the

resulting rise in consumer

demand) by investing more.

But this rise in investment

will

constitute

a further rise in injections

and thus will lead to a

second multiplies rise in

income.

And

so on...

The

reason why such an

interaction cannot raise

output infinitely is because of

two reasons i)

the

economy runs into the

full-employment constraint, i.e.

there is a fixed number of

workers in

the

economy, and ii) output

must grow at an increasing

rate (something which is

difficult to

sustain

for very long) in order

for investment to continue

rising. This is because the

accelerator

links

investment to changes in output,

not the level of output. So

for e.g., if output rises in

year

1

by Rs.3bn, in year 2 by Rs.2bn,

and in year 3 by Rs.1bn,

then with α

= 2,

investment will be

Rs.6bn,

Rs.4bn, and Rs.2bn in years

1, 2 and 3 respectively. As can be

seen, I falls even

though

output is rising, leading to a

reverse multiplier accelerator

chain reaction to be set

off

effect

will be reversed. The key

point to remember, again, is

that investment is related

to

"changes

in income" not the "level of

income", and therefore

"changes in income" have

to

increase

in order for investment to

increase. A mere increase in

level is not

important.

101

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

END

OF UNIT 10 - EXERCISES

What

are the conditions for

macroeconomic equilibrium in the

economy.

i.

Injections (governemnt spending,

exports, investment) into

the circular flow of

incomes

must equal the withdrawals

(saving, taxes, imports)

from the circular

flow;

or

ii.

Aggregate demand must equal

aggregate income must equal

aggregate supply.

The

two approaches are

equivalent. Note, however,

that the equilibrium of an

economy, at least

in

a Keynesian world, does not

imply the full-employment

equilibrium. It is possible

for

inflationary

and deflationary gaps to

exist.

What

are the major macroeconomic

variables involved in the

determination of national

income?

C,

I, G, X, M, T, S, prices, exchange rate,

interest rate and money

supply. We focus on the

first

seven

in this part of the course,

but will enrich our

analysis with the remaining

four later in the

context

of the IS-LM approach to

equilibrium determination and

international finance

considerations.

What

does the 45 degree line in

expenditure-income space

represent?

It

represents all the points at

which the economy is in

equilibrium, i.e. the

expenditure on

domestic

goods and services is equal

to the supply of domestic

goods and services is equal

to

the

incomes distributed to factors

used in the production of

those goods and

services

Are

the following net

injections, net withdrawals or

neither? If there is

uncertainty,

explain

your assumptions.

i.

Firms spend money on

research.

ii.

The government increases

personal tax

allowances.

iii.

The general public deposits

more money in

banks.

iv.

Pakistani investors earn

higher dividends on overseas

investments.

v.

The government purchases US

military aircraft.

vi.

People draw on their savings

to finance holiday trips

abroad.

vii.

People draw on their savings

to finance holidays within

Pakistan.

viii.The

government runs a budget

deficit (spends more than it

receives in tax

revenues)

and finances it by borrowing

from the general

public.

ix.

The government runs a budget

deficit and finances it by

printing more

money.

i.

Increase

in injections (investment).

ii.

Decrease

in withdrawals (taxes).

iii.

Increase

in withdrawals (saving).

iv.

Fall

in withdrawals (a reduction in net

outflow abroad from the

household sector).

v.

Neither.

The inner flow is

unaffected. If, however,

this were financed from

higher

taxes,

it would result in an increase in

withdrawals.

vi.

Neither. The inner flow is

unaffected. The consumption of

domestically produced

goods

and services remains the

same.

vii.

Decrease in withdrawals

(saving).

viii.

Neither. An increase in government

expenditure (or decrease in

taxes, or both) is

offset

by an increase in saving (i.e.

people buying government

securities).

ix.

Net injections. An increase in

government expenditure (or

decrease in taxes, or

both)

is not offset by changes

elsewhere. Extra money is

printed to finance the

net

injection.

102

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

It

is possible that as people

get richer they will

spend a smaller and smaller

fraction of

each

rise in income (and save a

larger fraction). Why might

this be so? What effect

will it

have

on the shape of the

consumption function?

It

is likely that the rich

will feel that they

can afford to save a larger

proportion of their

income

than

the poor. The consumption

function will slope upwards,

but get less and

less steep. This

means

mpc will fall as incomes

rise.

What

effect will the following

have on the mpc:

a)

a rise in the rate of income

tax;

b)

people anticipate that the

rate of inflation is about to

rise;

c)

the government redistributes

income from the rich to

the poor?

a)

The mpc will fall.

Note that here we are

relating consumption to gross

income. For any

given

gross income, a rise in

taxes will cause a fall in

disposable income and hence

a fall

in

consumption.

b)

The mpc will rise as

people spend a larger

fraction of any rise in

income, for if they

wait

to

consume, their incomes will

be worth less in the enxt

period in urchasing power

terms.

c)

The mpc will increase,

because the poor have a

higher mpc than the

rich.

What

would be the impact of

changing the determinant

variables given in the first

column

(below)

on consumption and saving.

Must saving always fall if

consumption falls?

Determinant

Consumption

Saving

Income

(rise)

rise

rise

Assets

held (increase in)

rise

fall

Taxation

(fall)

rise

rise

Cost

of credit (lower interest

rates)

rise

fall

Expectations

(that prices will

rise)

rise

fall

Redistribution

of income (becomes more

equal)

rise

fall

Tastes

and attitudes (people want

to consume more)

rise

fall

The

average age of durables

(increases)

rise

fall

Thus

there are two determinants

of consumption (namely income

and taxation, which will

not

cause

saving to rise if consumption is

caused to fall.

Why,

if the growth in output

slows down (but is still

positive), is investment likely to

fall

(i.e.

be negative)?

Because

firms will require a smaller

increase in capital. They

will thus buy fewer

extra machines

and

other equipment: i.e.

investment will fall. The

underlying concept is that of

Keynes's

investment

accelerator which relates

induced investment to changes in

output rather than

the

level

of output.

103

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

Give

some other examples of

changes in one injection or

withdrawal that can

affect

others.

�

A

rise in government expenditure on

infrastructure projects may

encourage firms to

invest,

or,

on the other hand, may

replace private

investment.

�

A

rise in taxation will reduce

savings and imports as well

as consumption of domestic

goods

and services.

�

A

depreciation of the exchange

rate will lead to increased

exports (an injection)

and

decreased

imports (a withdrawal). This

could encourage increased

investment in the

domestic

economy.

�

Higher

savings will mean less

total consumption, including

less expenditure on

imports.

Keeping

Keynes's paradox of thrift

arguments in mind, is an increase in

saving ever

desirable?

Yes.

�

If

there is a problem of excess

demand, an increase in savings

will reduce

inflationary

pressures.

�

If

investment increases over

time, an increase in savings

will allow these increases

to be

financed

without problems of rising

interest rates or inflation,

problems which would

have

the

effect of curtailing the

investment.

The

present level of a country's

exports is �12 billion;

investment is �2 billion;

government

expenditure is �4 billion; total

consumer spending (including on

imports) is

�36

billion; imports are �12

billion and expenditure

taxes are �2 billion. The

economy is

currently

in equilibrium. It is estimated that an

income of �50 billion is

necessary to

generate

full employment. The

marginal propensity to save is

0.25.

a)

Is there an inflationary or deflationary

gap in this

situation?

b)

What is the size of the

gap? (Don't confuse

this with the

difference

between

Ye and

Yf.)

c)

What would be an appropriate

government policy to close

this gap?

Injections

(J) = �12bn + �2bn + �4bn =

�18bn

Domestic

consumption (Cd)

= �36bn �12bn �2bn =

�22bn

∴

Expenditure on

domestic goods, E = Cd +

J = �18 + �22 = �40bn

Multiplier

= 1/mps = 1/0.25

=4

a)

Deflationary gap. If the

economy is in equilibrium, then Y = E.

Thus Ye =

�40bn. But full

employment

is achieved at an income of �50bn.

There is thus a deflationary

gap.

b)

�2.5bn. This is the amount

that must be injected (given

a multiplier of 4) in order to

increase

national income by �10bn

from the current �40bn to

the full-employment level

of

�50bn.

c)

Increase government expenditure by

�2.5bn.

Why

does investment in construction

and producer goods

industries tend to

fluctuate

more

than investment in retailing

and the service

industries?

Because

demand for the output of

these industries (which are

`investment' goods

industries)

fluctuates

much more as a result of the

accelerator effect.

Give

some examples of single

shocks and continuing

changes on the demand

side.

Does

the existence of multiplier

and accelerator effects make

the distinction

between

single

shocks and continuing

effects more difficult to

make on the demand side

than on

the

supply side?

Examples

of single shocks include

government expenditure on a specific

project, a surge in

consumer

spending in anticipation of a rise in

taxes and a temporary

movement in the

exchange

104

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

rate

(a depreciation causing a rise in

aggregate demand through

increased exports and

decreased

imports, and an appreciation

causing a fall in aggregate

demand). Examples of

continuing

changes include a sustained

increase in consumer or business

confidence, which

builds

over time, and changes in

interest rates that then

remain for a period of time.

The

multiplier

and accelerator will amplify

single shocks on the demand

side and the process

will last

for

several months. Aggregate

demand will not go on and on

rising, however, unless

there are

continuing

changes on the demand side,

which then continue to be

amplified by the

multiplier

and

accelerator. Thus the

effects are somewhat less

clear cut than with

changes on the supply

side,

but it is still possible to

distinguish between single

shocks on the demand side

and

continuing

changes (even if the single

shocks do cause multiplier

and accelerator

effects).

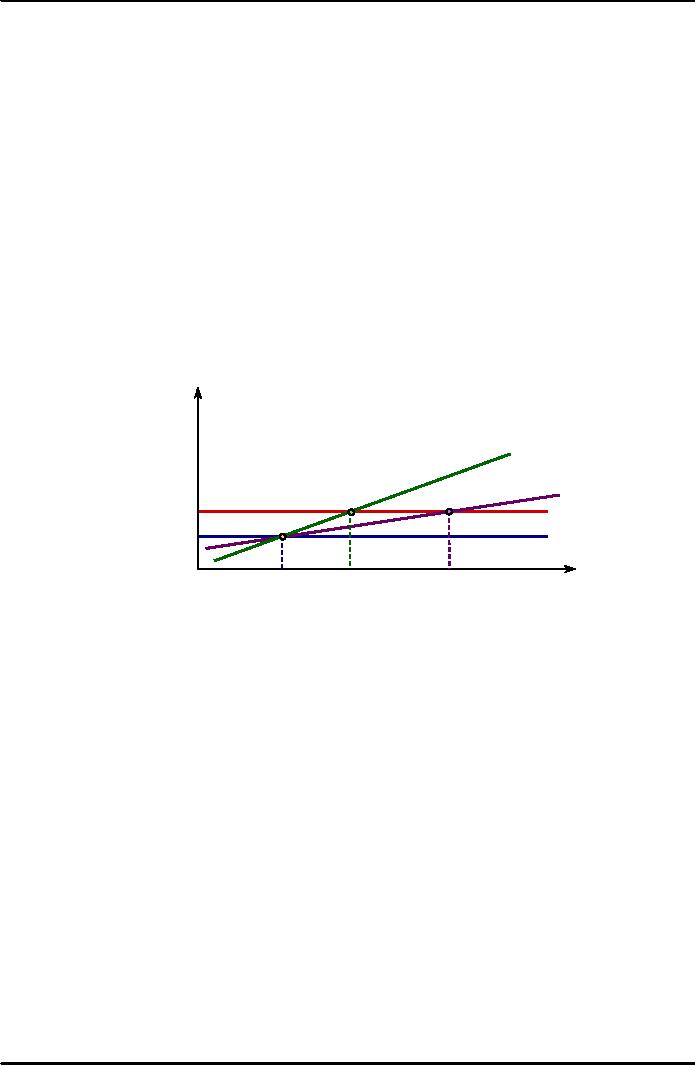

Draw

an injections and withdrawals

diagram, with a fairly

shallow W curve. Mark

the

equilibrium

level of national income.

Now draw a second steeper W

curve passing

through

the same point. This

second W curve would

correspond to the case where

the

mps

is higher.

Assuming

now that there has

been an increase in injections,

draw a second J line above

the

first.

Mark the new equilibrium

level of national income

with each of the two W

curves. You can

see

that national income rises

less with the steeper W

curve. The higher mps

has a

W,

J

Weconomy

2

Weconomy

1

J2

J1

O

Y0

Y2

Y1

Y

Economies

with different marginal

rates of taxation

dampening

effect on the multiplier. A

higher tax rate has

the same dampening effect as

well by

reducing

the size of the multiplier

(by increasing the size of

the term in the

denominator).

Multiplier

with taxes = 1/[1-{mpc(1-t)}];as t

increases, (1-t) falls,,

therefore 1-{.} rises,

causing

the

multiplier to fall.

What

effects will government

investment expenditure have on

public-sector debt (a)

in

the

short run; (b) in the

long run?

a)

Increase. Unless financed by

extra taxation, an increase in

government expenditure

(for

whatever

purpose) will lead to an

increase in public-sector

debt.

b)

Possibly decrease. If the

investment leads to extra

output and income, then

the extra tax

revenue

from the extra incomes

and expenditure could more

than offset the cost of

the

investment,

thereby leading to a fall in

public-sector debt.

If

cuts in interest rates are

not successful in causing

significant increases in

investment,

how can they lead to

economic recovery? What, in

these circumstances,

determines

the magnitude of the

recovery?

They

can lead to recovery if they

cause consumers to borrow

more. The increased

spending

causes

a multiplied rise in national

income. The magnitude of the

recovery depends on (a)

the

amount

of extra consumer spending;

(b) the size of the

multiplier; (c) whether

there is any

subsequent

increase in investment (through

the accelerator

effect).

105

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

How

do people's expectations influence

the outcome?

People's

expectations will reinforce

whatever it is they expect

(self-fulfilling expectations). If

firms

expect a rise in government

expenditure to lead to a) higher

interest rates, b) a reduction

in

private-sector

investment and hence c) no

expansion of the economy,

they will reduce

their

investment

plans, thus bringing about

the effect (i.e. economic

stagnation) that they

had

anticipated.

If

the government increases

spending by Rs.10bn and

finances it totally from

taxes, will

there

be any expansionary impact on

output?

Yes.

The increase in spending is an

injection of Rs.10 bn. The

withdrawal, however, is less

than

Rs.10bn,

as saving (a withdrawal from

the system falls). Why

does saving fall? Because

higher

taxes

reduce disposable income and

therefore given a fixed mps

out of disposable

income,

saving

will fall. The concept is

called balanced budget

multiplier, i.e. the fact

that tax-financed

spending

(which has no effect on the

fiscal balance) can still be

expected to have a

multiplied

(albeit

much smaller) effect on

equilibrium output and

income.

106

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO ECONOMICS:Economic Systems

- INTRODUCTION TO ECONOMICS (CONTINUED………):Opportunity Cost

- DEMAND, SUPPLY AND EQUILIBRIUM:Goods Market and Factors Market

- DEMAND, SUPPLY AND EQUILIBRIUM (CONTINUED……..)

- DEMAND, SUPPLY AND EQUILIBRIUM (CONTINUED……..):Equilibrium

- ELASTICITIES:Price Elasticity of Demand, Point Elasticity, Arc Elasticity

- ELASTICITIES (CONTINUED………….):Total revenue and Elasticity

- ELASTICITIES (CONTINUED………….):Short Run and Long Run, Incidence of Taxation

- BACKGROUND TO DEMAND/CONSUMPTION:CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

- BACKGROUND TO DEMAND/CONSUMPTION (CONTINUED…………….)

- BACKGROUND TO DEMAND/CONSUMPTION (CONTINUED…………….)The Indifference Curve Approach

- BACKGROUND TO DEMAND/CONSUMPTION (CONTINUED…………….):Normal Goods and Giffen Good

- BACKGROUND TO SUPPLY/COSTS:PRODUCTIVE THEORY

- BACKGROUND TO SUPPLY/COSTS (CONTINUED…………..):The Scale of Production

- BACKGROUND TO SUPPLY/COSTS (CONTINUED…………..):Isoquant

- BACKGROUND TO SUPPLY/COSTS (CONTINUED…………..):COSTS

- BACKGROUND TO SUPPLY/COSTS (CONTINUED…………..):REVENUES

- BACKGROUND TO SUPPLY/COSTS (CONTINUED…………..):PROFIT MAXIMISATION

- MARKET STRUCTURES:PERFECT COMPETITION, Allocative efficiency

- MARKET STRUCTURES (CONTINUED………..):MONOPOLY

- MARKET STRUCTURES (CONTINUED………..):PRICE DISCRIMINATION

- MARKET STRUCTURES (CONTINUED………..):OLIGOPOLY

- SELECTED ISSUES IN MICROECONOMICS:WELFARE ECONOMICS

- SELECTED ISSUES IN MICROECONOMICS (CONTINUED……………)

- INTRODUCTION TO MACROECONOMICS:Price Level and its Effects:

- INTRODUCTION TO MACROECONOMICS (CONTINUED………..)

- INTRODUCTION TO MACROECONOMICS (CONTINUED………..):The Monetarist School

- THE USE OF MACROECONOMIC DATA, AND THE DEFINITION AND ACCOUNTING OF NATIONAL INCOME

- THE USE OF MACROECONOMIC DATA, AND THE DEFINITION AND ACCOUNTING OF NATIONAL INCOME (CONTINUED……………..)

- MACROECONOMIC EQUILIBRIUM & VARIABLES; THE DETERMINATION OF EQUILIBRIUM INCOME

- MACROECONOMIC EQUILIBRIUM & VARIABLES; THE DETERMINATION OF EQUILIBRIUM INCOME (CONTINUED………..)

- MACROECONOMIC EQUILIBRIUM & VARIABLES; THE DETERMINATION OF EQUILIBRIUM INCOME (CONTINUED………..):The Accelerator

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS (CONTINUED…….)

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS (CONTINUED…….):Causes of Inflation

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS (CONTINUED…….):BALANCE OF PAYMENTS

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS (CONTINUED…….):GROWTH

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS (CONTINUED…….):Land

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS (CONTINUED…….):Growth-inflation

- FISCAL POLICY AND TAXATION:Budget Deficit, Budget Surplus and Balanced Budget

- MONEY, CENTRAL BANKING AND MONETARY POLICY

- MONEY, CENTRAL BANKING AND MONETARY POLICY (CONTINUED…….)

- JOINT EQUILIBRIUM IN THE MONEY AND GOODS MARKETS: THE IS-LM FRAMEWORK

- AN INTRODUCTION TO INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND FINANCE

- PROBLEMS OF LOWER INCOME COUNTRIES:Poverty trap theories: