|

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

Lesson

4.4

BACKGROUND

TO DEMAND/CONSUMPTION

(CONTINUED................)

Normal

Goods and Giffen

Good:

A

normal good is one whose

consumption increases when

income increases, while

inferior

good

is one whose consumption

decreases with increase in

income.

A

Giffen good is a sub-category of

inferior goods; its

consumption increases when

it's price

increases.

This is because of its very

strong income effect.

Both

normal and inferior goods

have downward sloping demand

curves.

The

Income Consumption Curve

(ICC) and Price Consumption

Curve (PPC):

The

income consumption curve

(ICC) can be used to derive

the Engel Curve, which

shows the

relationship

between income and quantity

demanded.

The

price consumption curve

(PCC) traces out the

optimal choice of consumption at

different

prices.

The PCC can be used to

derive the demand curve,

which shows the

relationship

between

price & quantity

demanded.

When

the price of one good

change, two things

happen:

�

One

the purchasing power of

consumer changes i.e., the

budget line shifts (leads

to

income

effect).

�

Secondly,

the slope of budget line

changes due to a change in

the relative price

ratio

(leads

to substitution effect).

The

substitution effect of a price

rise is always negative,

while the income

effect of a

price

rise

on the consumption of a normal

good is negative. The

income effect for an

inferior good

is

positive. The income effect

of a Giffen good is so positive

that it offsets the

negative

substitution

effect, therefore.

Limitation

of Indifference Approach:

The

indifference curves approach

has the following

limitations:

a.

Indifference curve analysis is

only possible for 2 or at

best for 3 goods.

b.

It is almost impossible to practically

derive indifference

curves.

c.

The consumer may not

always behave

rationally.

d.

The consumer may not

always realize the level of

utility (ex-post) from

consumption,

that

she originally expected

(ex-ante).

e.

Indifference curve analysis

can not help when

one of the goods (X or Y) is a

durable

good.

32

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

END

OF UNIT 4 - EXERCISES

Do

you ever purchase things

irrationally? If so, what

are they and why is

your

behaviour

irrational?

A

good example is things you

purchase impulsively, when in

fact you do have time to

reflect

on

whether you really want

them. It is not a question of

ignorance but a lack of

care. Your

behaviour

is irrational because the

marginal benefit of a bit of

extra care would exceed

the

marginal

effort involved.

Imagine

that you are going

out for the evening

with a group of friends. How

would you

decide

where to go? Would this

decision-making process be described as

`rational'

behaviour?

You

would probably discuss it

and try to reach a consensus

view. The benefits to you

(and to

other

group members) would

probably be maximized in this

way. Whether these

benefits

would

be seen as purely `selfish' on

the part of the members of

the group, or whether

people

have

more genuinely unselfish

approach, will depend on the

individuals involved.

If

you buy something in the

shop on the corner when

you know that the

same item

could

have been bought more

cheaply two miles up the

road from the

wholesale

market,

is your behaviour irrational?

Explain.

Not

necessarily. If you could

not have anticipated wanting

the item and if it would

cost you

time

and effort and maybe

money (e.g. petrol) to go to

the wholesale market, then

your

behaviour

is rational. Your behaviour a

few days previously would

have be irrational,

however,

if,

when making out your

weekly shopping list for

the wholesale market, a

moment's thought

could

have saved you having to

make the subsequent trip to

the shop on the

corner.

Are

there any goods or services

where consumers do not

experience diminishing

marginal

utility?

Virtually

none, if the time period is

short enough. If, however,

we are referring to a long

time

period,

such as a year, then

initially as more of an item is

consumed people may start

`getting

more

of a taste for it' and

thus experience increasing

marginal utility. But even

with such

items,

eventually, as consumption increases,

diminishing marginal utility

will be experienced.

If

Ammaar were to consume more

and more crisps, would

his total utility ever

(a) fall to

zero;

(b) become negative?

Explain.

Yes,

both. If he went on eating

more and more, eventually he

would feel more

dissatisfied

than

if he had never eaten any in

the first place. He might

actually be physically

sick!

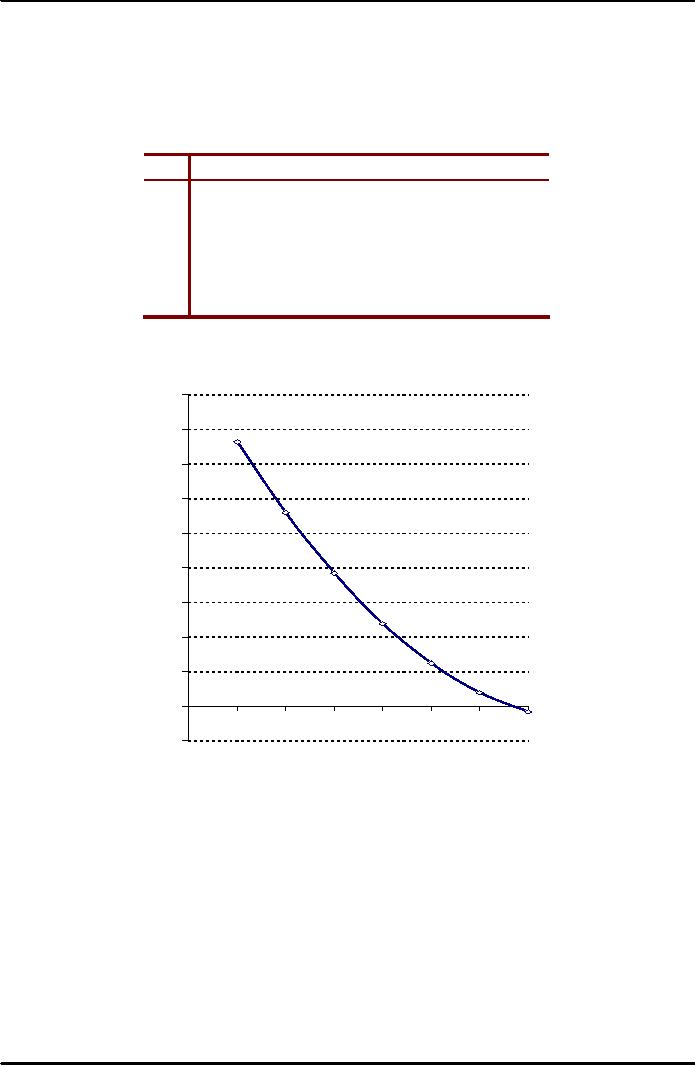

Complete

this table to the level of

consumption at which total

utility (TU) is at a

maximum,

given

the utility function TU = Q +

60Q 4Q2.

4Q2

Q

60Q

=

TU

1

60

4

=

56

2

120

16

=

104

3

180

36

=

144

4

240

64

=

176

5

300

100

=

200

6

360

144

=

216

7

420

196

=

224

8

480

256

=

224

Derive

the MU function from the

following TU function:

33

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

TU

= 200Q 25Q� + Q�

From

this MU function, draw up a

table (like the one

above) up to the level of Q

where MU

becomes

negative. Graph these

figures.

MU

= dTU/dQ = 200 50Q +

3Q�

3Q2

Q

MU

200

50Q

+

=

1

200

50

+

3

=

153

2

200

100

+

12

=

112

3

200

150

+

27

=

77

4

200

200

+

48

=

48

5

200

250

+

75

=

25

6

200

300

+

108

=

8

7

200

350

+

147

=

3

180

160

140

120

100

80

60

40

20

MU

0

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

-2

0

If

a good were free, why would

total consumer surplus equal

total utility? What would

be

the

level of marginal

utility?

Because

there would be no expenditure. At

the point of maximum

consumer surplus,

marginal

utility

would be equal to zero,

since if P = 0, and MU = P, then MU =

0.

Why

do we get less consumer

surplus from goods where

our demand is

relatively

elastic?

Because

we would not be prepared to

pay such a high price

for them. If price went

up, we

would

more readily switch to

alternative products.

How

would marginal utility and

market demand be affected by a

rise in the price of

a

complementary

good?

Marginal

utility and market demand

would fall (shift to the

left). The rise in the

price of the

complement

would cause less of it to be

consumed. This would

therefore reduce the

marginal

34

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

utility

of the other good. For

example, if the price of

lettuce goes up and as a

result we consume

less

lettuce, the marginal

utility of mayonnaise will

fall.

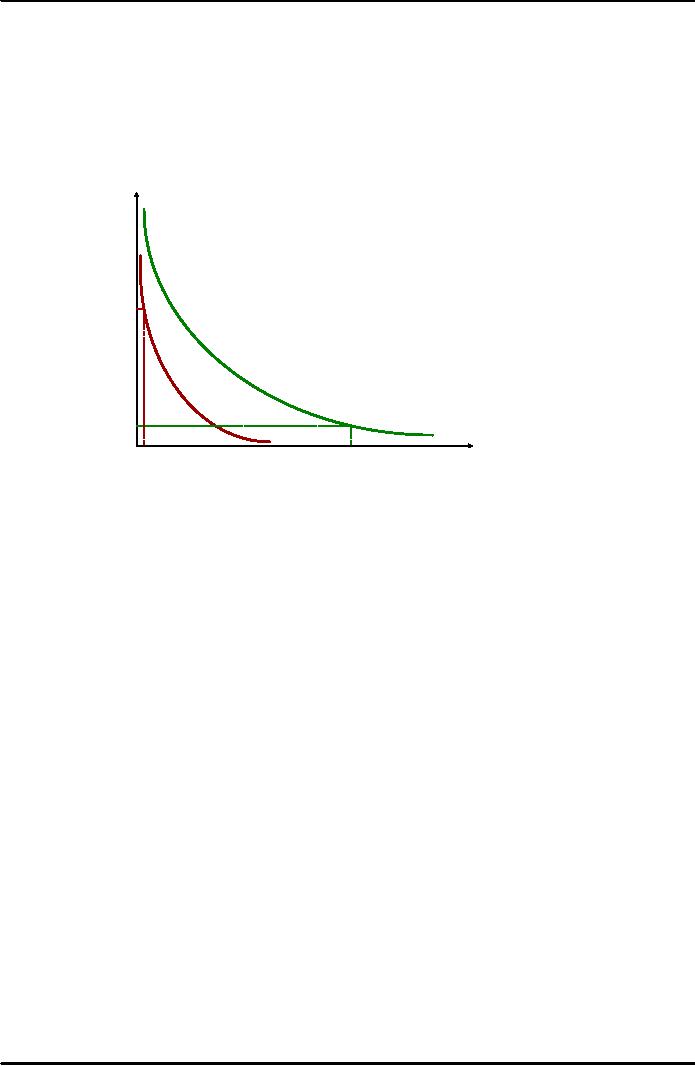

The

diagram illustrates a person's MU

curves of water and

diamonds. Assume

that

diamonds

are more expensive than

water. Show how the MU of

diamonds will be

greater

than

the MU of water. Show also

how the TU of diamonds will

be less than the TU

of

water.

MU,

P

Pd

Pw

MU

water

MU

diamonds

Qd

Qw

Define

`risk' and

`uncertainty'.

Risk:

when an outcome may or may

not occur, but its

probability of occurring is

known.

Uncertainty:

when an outcome may or may

not occur and its

probability of occurring is

not

known.

Give

some examples of gambling

(or risk taking in general)

where the odds are

(a)

unfavorable;

(b) fair; (c)

favourable.

a.

Betting on the horses; firms

launching a new product in a

market that is already

virtually

saturated

and where the firm

does not bother to

advertise.

b.

Gambling on a private game of

cards which is a game of

pure chance; deciding which

of

two

alternative brands to buy

when they both cost

the same and you

have no idea which

you

will like the

best.

c.

The buying and selling of

shares on the stock exchange

by dealers who are skilled

in

predicting

share price movements; not

taking an umbrella when the

forecast is that it

will

not

rain (weather forecasts are

right more often than

they are wrong!); an

employer

taking

on a new manager who has

excellent references from

previous employers.

(Note

that in the cases of (a)

and (c) the actual

odds may not be known,

only that they

are

unfavorable

or favourable.)

Which

game would you be more

willing to play, a 60:40

chance of gaining or losing

Rs10

000,

or a 40:60 chance of gaining or

losing Re1? Explain

why.

Most

people would probably prefer

the 40:60 chance of gaining

or losing Re1. The reason

is

that,

given the diminishing

marginal utility of income,

the benefit of gaining Rs10

000 may be

considerably

less than the costs of

losing Rs10 000, and

this may be more than

enough to deter

people,

despite the fact that

the chances of winning are

60:40.

Do

you think that this

provides a moral argument

for redistributing income

from the rich

to

the poor? Does it prove

that income should be so

redistributed?

35

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

Arguments

like this are frequently

used to justify redistributing

income and form part of

people's

moral

code. Most people would

argue that the rich

ought to pay more in taxes

than the poor

and

that

the poor ought to receive

more state benefits than

the rich. The argument is

frequently

expressed

in terms of a pound being

worth more to a poor person

than a rich person. It

does

not

prove that income should be

so redistributed, however, unless

you argue (a) that

the

government

ought to increase total

utility in society and (b)

that it is possible to compare

the

utility

gained by poor people with

that lost by rich people

something that is virtually

impossible

to

do.

What

details does an insurance

company require to know

before it will insure a

person to

drive

a car?

Age;

sex; occupation; accident

record; number of years that

a license has been held;

traffic law

violations

and convictions; model and

value of the car; age of

the car; details of other

drivers of

the

car.

How

will the following reduce

moral hazard?

a.

A no-claims bonus.

b.

The driver having to pay

the first so many rupees of

any claim (called

"excess").

c.

Offering lower premiums to

those less likely to claim

(e.g. if a house has a

burglar alarm,

it

is less likely to be burgled

and therefore the insurance

premiums for its contents

TV,

VCR,

etc. can be reduced by the

insurance company).

In

the case of (a) and

(b) people will be more

careful as they would incur

a financial loss if

the

event

they were insured against

occurred (loss of no-claims

bonus; paying the first so

much of

the

claim). In the case of (c)

it distinguishes people more

accurately according to risk.

It

encourages

people to move into the

category of those less

likely to claim (but it does

not make

people

more careful within a

category: e.g. those with

burglar alarms may be less

inclined to turn

them

on if they are well

insured!).

If

people are generally risk

averse, why do so many people around

the world take part

in

national

lotteries?

Because

the cost of taking part is

so little, that they do not

regard it as a sacrifice. They

also are

likely

to take a `hopeful' view

(i.e. not based on the

true odds) on their chances

of winning. What

is

more, the act of taking

part itself gives pleasure.

Thus the behaviour can

still be classed as

`rational':

i.e. one where the

perceived marginal benefit of

the gamble exceeds the

marginal cost.

Why

are insurance companies

unwilling to provide insurance

against losses arising

from

war

or `civil disorder'?

Because

the risks are not

independent. If family A has

its house bombed, it is more

likely that

family

B will too.

Name

some other events where it

would be impossible to obtain

insurance.

Against

losses on the stock market;

against crop losses

resulting from

drought.

Although

indifference curves will

normally be bowed in toward

the origin, on

odd

occasions

they might not be.

What would indifference

curves look like in each of

the

following

cases?

a.

X and Y are left shoes

and right shoes.

b.

X and Y are two brands of

the same product, and

the consumer cannot tell

them

apart.

c.

X is a good but Y is a `bad'

like household

refuse.

a.

L-shaped. An additional left

shoe will give no extra

utility without an additional

right shoe

to

go with it!

b.

Straight lines. The consumer

is prepared to go on giving up one

unit of one brand

provided

that it is replaced by one

unit of the other

brand.

36

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

c.

Upward sloping. If consumers

are to be persuaded to put up

with more of the `bad',

they

must

have more of the good to

compensate.

What

will happen to the budget

line if the consumer's

income doubles and the

price of

both

X and Y double?

It

will not move. Exactly

the same quantities can be

purchased as before. Money

income has

risen,

but real income has

remained the same.

The

incomeconsumption curve is often

drawn as positively sloped at

low levels of

income.

Why?

Because

for those on a low level of

income the good is not

yet in the category of an

inferior

good.

Take the case of inexpensive

margarine. Those on very low

incomes may economise

on

their

use of it (along with all

other products), but as they

earn a little more, so they

can afford to

spread

it a little thicker or use it

more frequently (the

incomeconsumption curve is

positive).

Only

when their income rises

more substantially do they

substitute better quality

margarines or

butter.

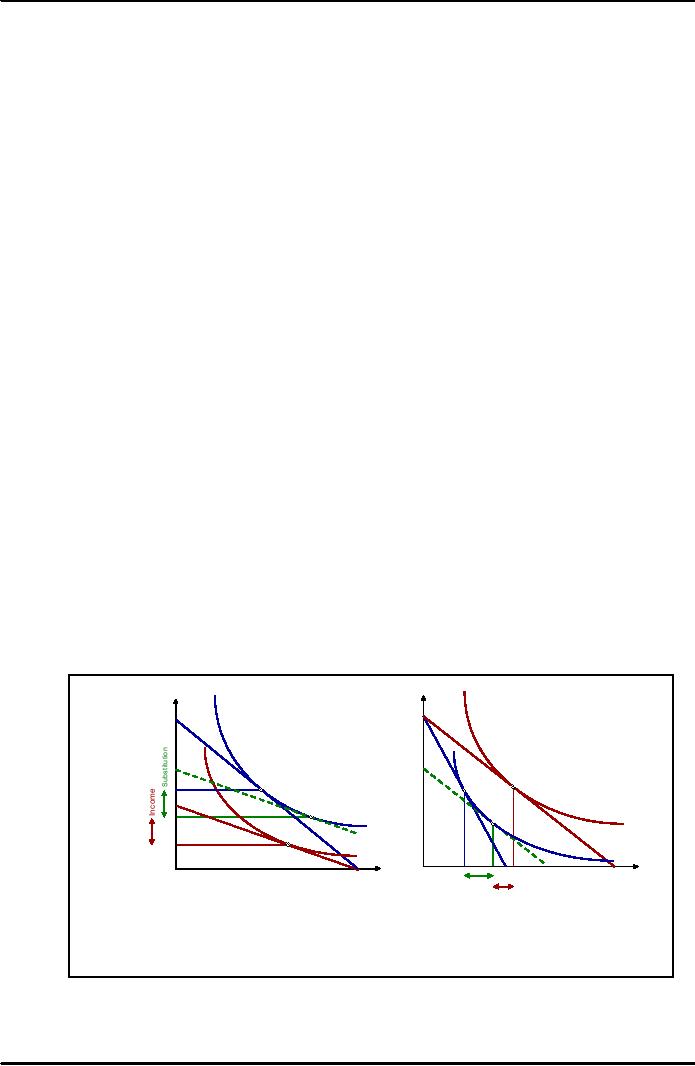

Illustrate

on an indifference diagram the

effects of the following: A

ceteris paribus (a)

rise

in

the price of good Y (b)

fall in the price of good

X.

a.

The budget line will

pivot inwards from B1 to

B2.

b.

The budget line would

pivot outward on the point

where the budget line

crosses the

vertical

axis. It is likely that the

new tangency point with an

indifference curve

will

represent

an increase in the consumption of

both goods. The diagram

above can be

used

to illustrate this. Assume

the budget line pivots

outwards from B1 to B2.

The

optimum

consumption point will move

from point a to c.

Illustrate

the income and substitution

effects in the above

question.

See

the diagram above. In each

case the substitution effect

is shown by a movement from

point

a

to point b and the

substitution effect is shown by a

movement from point b to

point c.

Are

there any Giffen goods

that you consume? If

not, could you conceive of

any

circumstances

in which one or more items

of your expenditure would

become Giffen

goods?

Good

Y

Good

Y

B1

B1a

c

a

a

B2

b

b

I2

I1

c

B2

I2

B1

B1a

I1

Good

X

Substitution

Good

X

Income

(b)

Decrease

in price of X

(a)

Increase

in price of Y

37

Introduction

to Economics ECO401

VU

It

is unlikely that any of the

goods you consume are

Giffen goods. One

possible

exception

may be goods where you

have a specific budget for

two or more items,

where

one item is much cheaper:

e.g. fruit bought from a

greengrocer (or rehri

waala

on

the street). If, say,

apples are initially much

cheaper than bananas, you

may be able

to

afford some of each. Then

you find that apples

have gone up in price, but

are still

cheaper

than bananas. What do you

do? By continuing to buy

some of each fruit

you

may

feel that you are

not eating enough pieces of

fruit to keep you healthy

and so you

substitute

apples for bananas, thereby

purchasing more apples than

before (but

probably

less pieces of fruit than

originally).

38

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO ECONOMICS:Economic Systems

- INTRODUCTION TO ECONOMICS (CONTINUED………):Opportunity Cost

- DEMAND, SUPPLY AND EQUILIBRIUM:Goods Market and Factors Market

- DEMAND, SUPPLY AND EQUILIBRIUM (CONTINUED……..)

- DEMAND, SUPPLY AND EQUILIBRIUM (CONTINUED……..):Equilibrium

- ELASTICITIES:Price Elasticity of Demand, Point Elasticity, Arc Elasticity

- ELASTICITIES (CONTINUED………….):Total revenue and Elasticity

- ELASTICITIES (CONTINUED………….):Short Run and Long Run, Incidence of Taxation

- BACKGROUND TO DEMAND/CONSUMPTION:CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

- BACKGROUND TO DEMAND/CONSUMPTION (CONTINUED…………….)

- BACKGROUND TO DEMAND/CONSUMPTION (CONTINUED…………….)The Indifference Curve Approach

- BACKGROUND TO DEMAND/CONSUMPTION (CONTINUED…………….):Normal Goods and Giffen Good

- BACKGROUND TO SUPPLY/COSTS:PRODUCTIVE THEORY

- BACKGROUND TO SUPPLY/COSTS (CONTINUED…………..):The Scale of Production

- BACKGROUND TO SUPPLY/COSTS (CONTINUED…………..):Isoquant

- BACKGROUND TO SUPPLY/COSTS (CONTINUED…………..):COSTS

- BACKGROUND TO SUPPLY/COSTS (CONTINUED…………..):REVENUES

- BACKGROUND TO SUPPLY/COSTS (CONTINUED…………..):PROFIT MAXIMISATION

- MARKET STRUCTURES:PERFECT COMPETITION, Allocative efficiency

- MARKET STRUCTURES (CONTINUED………..):MONOPOLY

- MARKET STRUCTURES (CONTINUED………..):PRICE DISCRIMINATION

- MARKET STRUCTURES (CONTINUED………..):OLIGOPOLY

- SELECTED ISSUES IN MICROECONOMICS:WELFARE ECONOMICS

- SELECTED ISSUES IN MICROECONOMICS (CONTINUED……………)

- INTRODUCTION TO MACROECONOMICS:Price Level and its Effects:

- INTRODUCTION TO MACROECONOMICS (CONTINUED………..)

- INTRODUCTION TO MACROECONOMICS (CONTINUED………..):The Monetarist School

- THE USE OF MACROECONOMIC DATA, AND THE DEFINITION AND ACCOUNTING OF NATIONAL INCOME

- THE USE OF MACROECONOMIC DATA, AND THE DEFINITION AND ACCOUNTING OF NATIONAL INCOME (CONTINUED……………..)

- MACROECONOMIC EQUILIBRIUM & VARIABLES; THE DETERMINATION OF EQUILIBRIUM INCOME

- MACROECONOMIC EQUILIBRIUM & VARIABLES; THE DETERMINATION OF EQUILIBRIUM INCOME (CONTINUED………..)

- MACROECONOMIC EQUILIBRIUM & VARIABLES; THE DETERMINATION OF EQUILIBRIUM INCOME (CONTINUED………..):The Accelerator

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS (CONTINUED…….)

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS (CONTINUED…….):Causes of Inflation

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS (CONTINUED…….):BALANCE OF PAYMENTS

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS (CONTINUED…….):GROWTH

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS (CONTINUED…….):Land

- THE FOUR BIG MACROECONOMIC ISSUES AND THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIPS (CONTINUED…….):Growth-inflation

- FISCAL POLICY AND TAXATION:Budget Deficit, Budget Surplus and Balanced Budget

- MONEY, CENTRAL BANKING AND MONETARY POLICY

- MONEY, CENTRAL BANKING AND MONETARY POLICY (CONTINUED…….)

- JOINT EQUILIBRIUM IN THE MONEY AND GOODS MARKETS: THE IS-LM FRAMEWORK

- AN INTRODUCTION TO INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND FINANCE

- PROBLEMS OF LOWER INCOME COUNTRIES:Poverty trap theories: