|

TAGUCHI LOSS FUNCTION AND QUALITY MANAGEMENT |

| << LEADERS IN QUALITY REVOLUTION AND DEFINING FOR QUALITY:User-Based |

| WTO, SHIFTING FOCUS OF CORPORATE CULTURE AND ORGANIZATIONAL MODEL OF MANAGEMENT >> |

Total

Quality Management

MGT510

VU

Lesson

# 08

TAGUCHI

LOSS FUNCTION AND QUALITY

MANAGEMENT

Total

Quality Paradigms

Adopting

a TQ philosophy requires significant

changes in organization design, work

processes, and

culture.

Organizations use a variety of

approaches. Some emphasize the

use of quality tools, such

as

statistical

process control of Six Sigma

(which we discuss in the next chapter),

but have not made the

necessary

fundamental changes in their

processes and culture. It is easy to

focus on tools and techniques

but

very hard to understand and achieve the

necessary changes in human attitudes and

behavior. Others

have

adopted a behavioral focus in which the

organization's people are

indoctrinated in a customer-

focused

culture, or emphasize error

prevention and design quality, but

fail to incorporate

continuous

improvement

efforts. Still other

companies focus on problem-solving and

continuous improvements,

but

fail

to focus on what is truly important to

the customer. Although these firms

will realize limited

improvements,

the full potential of total

quality is lost due to a lack of complete

understanding by the

entire

organization.

Single

approaches, such as statistical

tools, behavioral change, or

problem solving can have

some short-

term

success, but do not seem to

work well over time.

Total quality requires a comprehensive

effort that

encompasses

all of these approaches. A

total change in thinking,

not a new collection of

tools, is

needed.

Total quality requires a set of

guiding principles. Such

principles have been promoted by

the

many

"quality gurus" Deming, Juran, and

Crosby, Ishikawa and Taguchi.

Their insights on measuring,

managing,

and improving quality have had profound

impacts on countless managers and

entire

corporations

around the world.

Defining

Quality as Loss

Function

Taguchi

(1986) suggests that there is increasing

loss, for the producer, the customer, and

society,

associated

with increasing variability, or deviation

from a target value that

reflects the "ideal state."

This

relationship

to variability can be expressed as a

loss function, as shown for the

distribution of rods

from

grinding

operation C, in Figure 12.

The greater the variability, deviation

from target, the greater the

loss

will

be.

Traditional

specifications, used in the manufacturing-based

approach to quality, define conformity

n

terms

of upper and lower specification

limits. For example steel

rods should meet the

engineering

specification

for length of six inches,

plus or minus 10 one-hundredths o an inch (6 + or _

.10). This

approach

tends to allow complacency concerning

variation within that range. It

assumes that a

product

just

barely meeting specifications,

just within the limit, is

just as "good" as on right in the

middle, but

one

just outside the limit is "bad."

Taguchi questions these assumptions,

and suggests the degree

of

"badness"

or "loss" increases gradually as the

deviation from the target

value increases.

Although

managers

may choose to do the right

thing (the target), in order

to provide superior value to

customers

through

superior "quality," they

must also continuously

improve their systems and

reduce variation to

meet

the target.20 In the 1980s, Motorola committed to a

campaign called Six Sigma, which is one

way

of

saying reduce variation so

much that the chance of

producing defects is down to

about 3.4 defects per

million,

or 99.99966 percent perfect.

30

Total

Quality Management

MGT510

VU

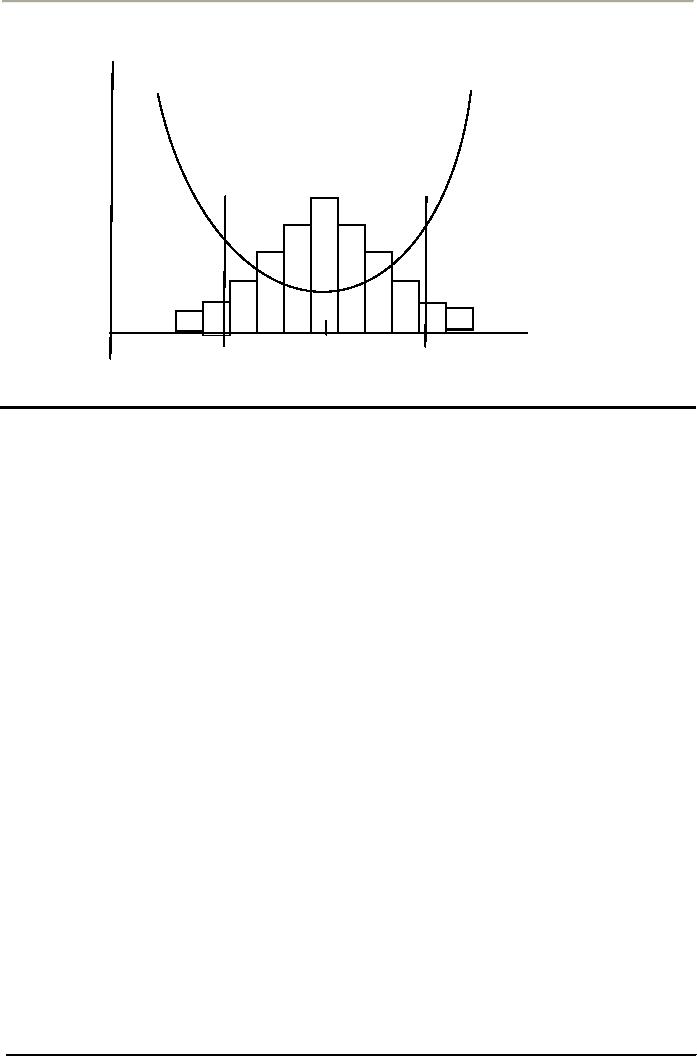

Taguchi's

loss function: loss

increases as a function of

variation

Loss

($)

Loss

($)

due

to variation

due

to variation

Distribution

of output

Length

of rod in

inches

6.1

6.0

5.9

USL

Target

LSL

The

Deming Management Philosophy

Deming

was trained as statistician and

worked for Western Electric

during its pioneering era

of

statistical

quality control development in the

1920s and 1930s. During

World War II he taught

quality

control

courses as part of the national

defense effort. Although

Deming taught many engineers in

the

United

States, he was not able to

reach upper management.

After the war, Deming was

invited to Japan

to

teach statistical quality

control concepts. Top

managers there were eager to learn, and

he addressed

21

to executives who collectively resented

80 percent of the county's capital. They

embraced Deming's

message

and transformed their industries. By the

mid-1970s, the quality of Japanese

products exceeded

that

of Western manufacturers, and Japanese

companies had made significant

penetration into

Western

markets.

Deming

taught quality to Japanese

and Ishikawa was Deming's

student. Americans did not

listen to

Deming

as attentively as Japanese did and

took his a prophet of

quality.

31

Table of Contents:

- OVERVIEW OF QUALITY MANAGEMENT:PROFESSIONAL MANAGERIAL ERA (1950)

- TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT AND TOTAL ORGANIZATION EXCELLENCE:Measurement

- INTEGRATING PEOPLE AND PERFORMANCE THROUGH QUALITY MANAGEMENT

- FUNDAMENTALS OF TOTAL QUALITY AND RATERS VIEW:The Concept of Quality

- TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT AND GLOBAL COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE:Customer Focus

- TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT AND PLANNING FOR QUALITY AT OFFICE

- LEADERS IN QUALITY REVOLUTION AND DEFINING FOR QUALITY:User-Based

- TAGUCHI LOSS FUNCTION AND QUALITY MANAGEMENT

- WTO, SHIFTING FOCUS OF CORPORATE CULTURE AND ORGANIZATIONAL MODEL OF MANAGEMENT

- HISTORY OF QUALITY MANAGEMENT PARADIGMS

- DEFINING QUALITY, QUALITY MANAGEMENT AND LINKS WITH PROFITABILITY

- LEARNING ABOUT QUALITY AND APPROACHES FROM QUALITY PHILOSOPHIES

- TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT THEORIES EDWARD DEMING’S SYSTEM OF PROFOUND KNOWLEDGE

- DEMING’S PHILOSOPHY AND 14 POINTS FOR MANAGEMENT:The cost of quality

- DEMING CYCLE AND QUALITY TRILOGY:Juran’s Three Basic Steps to Progress

- JURAN AND CROSBY ON QUALITY AND QUALITY IS FREE:Quality Planning

- CROSBY’S CONCEPT OF COST OF QUALITY:Cost of Quality Attitude

- COSTS OF QUALITY AND RETURN ON QUALITY:Total Quality Costs

- OVERVIEW OF TOTAL QUALITY APPROACHES:The Future of Quality Management

- BUSINESS EXCELLENCE MODELS:Excellence in all functions

- DESIGNING ORGANIZATIONS FOR QUALITY:Customer focus, Leadership

- DEVELOPING ISO QMS FOR CERTIFICATION:Process approach

- ISO 9001(2000) QMS MANAGEMENT RESPONSIBILITY:Issues to be Considered

- ISO 9001(2000) QMS (CLAUSE # 6) RESOURCES MANAGEMENT:Training and Awareness

- ISO 9001(2000) (CLAUSE # 7) PRODUCT REALIZATION AND CUSTOMER RELATED PROCESSES

- ISO 9001(2000) QMS (CLAUSE # 7) CONTROL OF PRODUCTION AND SERVICES

- ISO 9001(2000) QMS (CLAUSE # 8) MEASUREMENT, ANALYSIS, AND IMPROVEMENT

- QUALITY IN SOFTWARE SECTOR AND MATURITY LEVELS:Structure of CMM

- INSTALLING AN ISO -9001 QM SYSTEM:Implementation, Audit and Registration

- CREATING BUSINESS EXCELLENCE:Elements of a Total Quality Culture

- CREATING QUALITY AT STRATEGIC, TACTICAL AND OPERATIONAL LEVEL

- BIG Q AND SMALL q LEADERSHIP FOR QUALITY:The roles of a Quality Leader

- STRATEGIC PLANNING FOR QUALITY AND ADVANCED QUALITY MANAGEMENT TOOLS

- HOSHIN KANRI AND STRATEGIC POLICY DEPLOYMENT:Senior Management

- QUALITY FUNCTION DEPLOYMENT (QFD) AND OTHER TOOLS FOR IMPLEMENTATION

- BASIC SQC IMPROVEMENT TOOLS:TOTAL QUALITY TOOLS DEFINED

- HOW QUALITY IS IMPLEMENTED? A DIALOGUE WITH A QUALITY MANAGER!

- CAUSE AND EFFECT DIAGRAM AND OTHER TOOLS OF QUALITY:Control Charts

- STATISTICAL PROCESS CONTROL (SPC) FOR CONTINUAL QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

- STATISTICAL PROCESS CONTROL….CONTD:Control Charts

- BUILDING QUALITY THROUGH SPC:Types of Data, Defining Process Capability

- AN INTERVIEW SESSION WITH OFFICERS OF A CMMI LEVEL 5 QUALITY IT PAKISTANI COMPANY

- TEAMWORK CULTURE FOR TQM:Steering Committees, Natural Work Teams

- UNDERSTANDING EMPOWERMENT FOR TQ AND CUSTOMER-SUPPLIER RELATIONSHIP

- CSR, INNOVATION, KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AND INTRODUCING LEARNING ORGANIZATION