|

HISTORY OF QUALITY MANAGEMENT PARADIGMS |

| << WTO, SHIFTING FOCUS OF CORPORATE CULTURE AND ORGANIZATIONAL MODEL OF MANAGEMENT |

| DEFINING QUALITY, QUALITY MANAGEMENT AND LINKS WITH PROFITABILITY >> |

Total

Quality Management

MGT510

VU

Lesson

# 10

HISTORY

OF QUALITY MANAGEMENT

PARADIGMS

The

Evolution of Quality Approaches

The

shift to Total Quality

Management may be revolutionary

for many managers because

the tenets of

the

new paradigm are so

radically different from

past managerial practices. It

will require both a

thought

revolution

and a behavioral revolution. Approaches

to quality have evolved through a

series of gradual

refinements

over the last century. The

shift seems dramatic and

revolutionary to many

managers

because

they have not kept up with

the evolving approaches over the

years. However, they have

not

defined

their managerial roles in terms of the

latest advancements or they feel

skeptical about its

success.

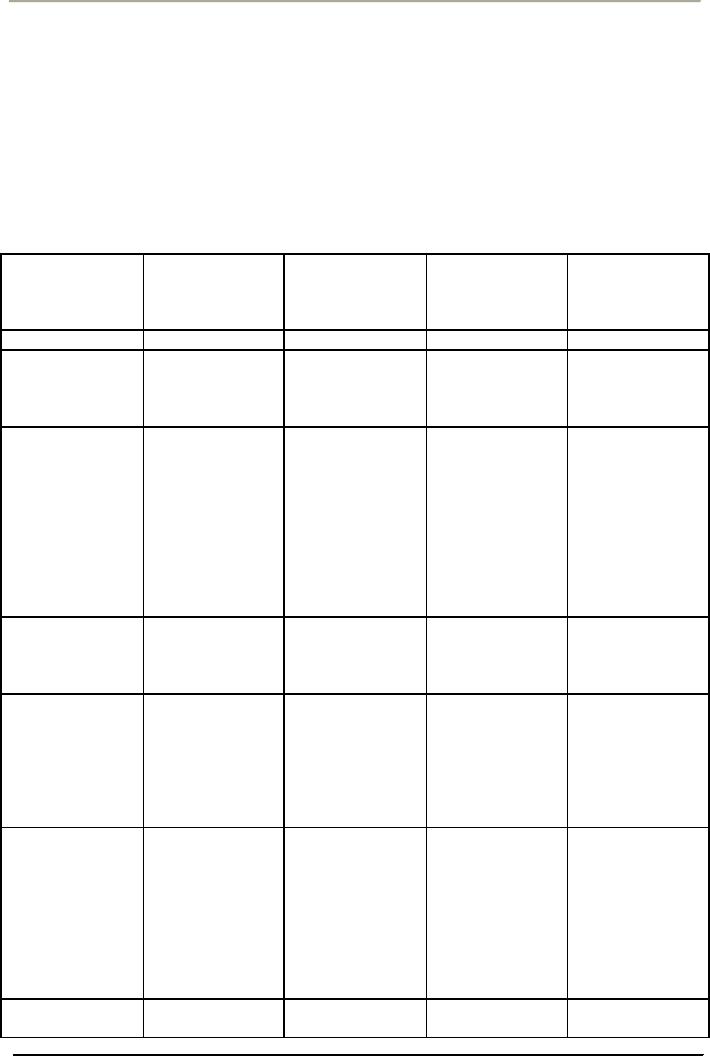

The

Four Major Quality

Eras

Identifying

Inspection

Statistical

Quality

Strategic

Total

Characteristics

(1800s)

Quality

Control

Assurance

Quality

Date

of inception

(1930s)

(1950s)

Management

(1980s)

Primary

concern

Detection

Control

Coordination

Strategic

impact

A

competitive

View

of quality

A

problem to be

A

problem to be

A

problem to be

opportunity

solved

solved

solved,

but one

that

is attacked

proactively

The

market and

Emphasis

Product

Product

uniformity The entire

consumer

needs

uniformity

with

reduced

production

chain,

inspection

from

design to

market,

and the

contribution

of all

functional

groups,

especially

designers,

to

preventing

quality

failures

Methods

Gauging

and

Statistical

tools

Programs

and

Strategic

planning,

measurement

and

techniques

systems

goal-setting,

and

mobilizing

the

organization

Role

of quality

Inspection,

Troubleshooting

Quality

Goal-setting,

professionals

sorting,

counting,

and

the application measurement,

education

and

and

grading

of

statistical

quality

planning,

training,

methods

and

program

consultative

work

design

with

other

departments,

and

program

design

Everyone

in the

Who

has

The

inspection

The

manufacturing All department,

organization,

with

responsibility

for

department

and

engineering

although

top

top

management

quality

departments

management

is

exercising

strong

only

peripherally

leadership

involved

in

designing,

planning,

and

executing

quality

policies

Orientation

and

"Inspects

in"

"Controls

in"

"Builds

in" quality "Manages

in"

approach

quality

quality

quality

34

Total

Quality Management

MGT510

VU

Customer-Craft

OR the Inspection Era

Until

the nineteenth century, skilled

craftsmen manufactured goods in small

volume. They handcrafted

and

fit together parts to form a

unique product that was

only informally inspected. Population

growth

and

industrialization brought about

production in larger volume.

Manufacturing in the

industrialized

world

tended to follow this craftsmanship model

till the factory system,

with its emphasis on

product

inspection,

started in Great Britain in

the mid-1750s and grew into

the Industrial Revolution in the

early

1800s.

The

factory system, a product of the

Industrial Revolution in Europe,

began to divide the craftsmen's

trades

into specialized tasks. This

forced craftsmen to become

factory workers and forced

shop owners

to

become production supervisors, and marked an

initial decline in employees'

sense of empowerment

and

autonomy in the workplace.

Quality

in the factory system was

ensured through the skill of laborers

supplemented by audits and/or

inspections.

Defective products were either reworked

or scrapped.

Mass

Production and Inspection

In

the 1800s, increased specialization,

division of labor, and mass

production required more

formal

inspection.

Parts had to be interchangeable. Inspectors

examined products to detect flaws

and separate

the

good from the bad. They used

gauges to catch deviant

parts and make sure parts

fit together at final

assembly.

The gauging system made

inspections more consistent than those

conducted solely by eye,

and

gave inspection a new

respectability.

Formalizing

the Inspection Function

By

the early 1900s, gauging had become more

refined, and inspection was even more

important. It was

prominent

in Henry Ford's moving

assembly line and Frederick

W. Taylor's system of shop

floor

management.

In 1922, G.S. Radford

formally linked inspection to

quality control. For the

first time,

quality

was regarded as an independent function

and a distinct management

responsibility. Radford

defined

quality in term of conformance to "established

requirements" and emphasized inspection.

He

also

suggested some lasting

quality principles, such as

getting designers involved

early, closely

coordinating

various departments, and achieving the

quality improvement results of

increased output

and

lower costs.

Late

in the 19th century the United

States broke further from

European tradition and adopted a

new

management

approach developed by Frederick W.

Taylor. Taylor's goal was to

increase productivity

without

increasing the number of skilled craftsmen. He achieved

this by assigning factory planning

to

specialized

engineers and by using craftsmen and supervisors,

who had been displaced by the growth

of

factories,

as inspectors and managers

who executed the engineers' plans.

Taylor's

approach led to remarkable rises in

productivity, but it had significant

drawbacks: Workers

were

once again stripped of their

dwindling power, and the new

emphasis on productivity had a

negative

effect on quality.

To

remedy the quality decline, factory

managers created inspection

departments to keep defective

products

from reaching customers. If

defective product did reach

the customer, it was more common

for

upper

managers to ask the inspector,

"Why did we let this get

out?" than to ask the

production manager,

"Why

did we make it this way to

begin with?"

Through

the 1920s, however, quality

control was most often

limited to inspection and

focused on

activities

such as counting, grading,

and rework, which is

antithetical to Total Quality

Management's

emphasis

on prevention to avoid defects.

Inspection departments and quality

professionals were not

35

Total

Quality Management

MGT510

VU

required

to troubleshoot, to understand and address the

causes of poor quality,

until the 1930s, with the

creation

of statistical quality

control.

In

the early 20th century, manufacturers

began to include quality

processes in quality practices.

After

the

United States entered World

War II, quality became a

critical component of the war effort:

Bullets

manufactured

in one place, for example, had to work

consistently in rifles made in

another. The armed

forces

initially inspected virtually every

unit of product; then to

simplify and speed up this

process

without

compromising safety, the military

began to use sampling techniques

for inspection, aided by

the

publication

of military-specification standards and

training courses in Walter

Shewhart's statistical

process

control techniques.

The

Statistical Quality Control

Era

In

1931, Walter A. Shewhart gave quality a

scientific footing with the

publication of his book

Economic

Control

of Quality of Manufactured Product. Shewhart

was one of a group of people at

Bell

Laboratories

investigating problems of quality. The

statistical quality control approach

that Shewhart

advocated

is based on his views of

quality. Statistical quality

control requires that numbers

derived from

measures

of processes or products be analyzed

according to a theory of variation

that links outcomes

to

uses.

Shewhart's

Views of Quality

Shewhart

offered a pragmatic concept of

quality: "The measure of

quality is a quantity which

may take

on

different numerical values. In other

words, the measure of quality, no mater

what the definition of

quality

may be, is a variable".

Shewhart's emphasis on measurement in

his definition of

quality

obviously

relates to his prescriptions

for statistical quality

control, which requires

numbers.

Shewhart

recognized that industrial processes

yield data. For example, a

process in which metal is

cut

into

sheets yields certain

measurements, such as each

sheet's length, height and

weight. Shewhart

determined

this data could be analyzed

using statistical techniques to see

whether a process is stable

and

in

control, or if it is being affected by

special causes that should be

fixed. In doing so, Shewhart

laid the

foundation

for control charts, a

modern-day quality

tool.

Shewhart's

concepts are referred to as

statistical quality control (SQC).

They differ from

product

orientation

in that they make quality

relevant not only for the

finished product but also

for the process

that

created it.

The

Quality Assurance Era

During

the quality assurance era, the

concept of quality in the United

States evolved from a

narrow,

manufacturing-based

discipline to one with implications

for management throughout a

firm. Statistics

and

manufacturing control remained important,

but coordination with other

areas, such as design,

engineering,

planning, and service activities,

also became important to

quality. While quality

remained

focused

on defect prevention, the quality

assurance era brought a more

proactive approach and

some

new

tools.

The

quality assurance era

significantly expanded the involvement of

all other functions through

total

quality

control, and inspired managers to

pursue perfection actively.

However, the approaches to

achieving

quality remained largely defensive.

Controlling quality still

meant acting on defects.

Quality

was

something that could hurt a

company if ignored, rather than a

positive characteristic necessary

in

obtaining

competitive advantage. This view

started to change in the 1970s

and 1980s, when

managers

started

to recognize the strategic importance of

quality.

36

Total

Quality Management

MGT510

VU

Total

Quality Control and Customer

Driven Quality

The

beginning of the 20th century marked the

inclusion of "processes" in quality

practices. A "process"

is

defined as a group of activities

that takes an input, adds

value to it and provides an

output, such as

when

a chef transforms a pile of ingredients

into a meal.

In

1956, Armand Feigenbaum extended this

principle by suggesting that high-quality

products are more

likely

to be produced through total quality

control than when

manufacturing works in

isolation:

The

underlying principle of this

total quality view. . . . is

that, to provide genuine

effectiveness,

control

must start with the design of the

product and end only when

the product has been

placed

in

the hands of a customer who

remains satisfied .. . . the first

principle to recognize is that

quality

is everybody's job.

The

birth of total quality in the

United States came as a

direct response to the quality

revolution in Japan

following

World War II. The Japanese

welcomed the input of Americans

Joseph M. Juran and W.

Edwards

Deming and rather than concentrating on

inspection, focused on improving

all organizational

processes

through the people who used

them.

Feigenbaum's

message reinforced Juran's

emphasis on managerial responsibility. To

make total quality

control

work, many companies

developed matrices or relationship

charts. These charts list

functions

(departments

or groups) across the top and required

activities down the side, and

shows responsibility

relationships

in each cell. The considerable

overlap among functions means

that cross-functional

teams

are

needed to ensure required

communication and collaboration, for

example, in assessing

the

"manufacturability"

of a design and debugging new

manufacturing techniques through pilot

runs.

Both

Juran and Feignebaum acknowledged that

statistical methods and manufacturing

control were still

important.

However, they also felt

total quality control would

require new management

skills to deal

with

areas such as new product

development and vendor selection.

Managers also would be

required to

engage

in activities such as quality

planning and coordinating

cross-functional teamwork. Despite

the

emphasis

on teamwork, Feigenbaum's TQC

suggests that more than half

of the primary responsibilities

for

quality belong to the quality

control department, another practice that is

antithetical to modern Total

Quality

Management.

W

Edwards Deming, a statistician with the

U.S. Department of Agriculture and

Census Bureau, became

a

proponent of Shewhart's SQC

methods and later became a leader of the

quality movement in both

Japan

and the United States.

The

Strategic Quality Management

Era

The

present quality era, Strategic

Quality Management, incorporates elements

of each of the preceding

eras,

particularly the contributions of Shewhart,

Deming, Juran, and Feigenbaum. So many

elements of

previous

eras are incorporated into

Strategic Quality Management that the

last two decades may at

first

appear

to be just a repackaging of old

ideas. There are, however,

dramatic differences from

earlier eras.

For

the first time, top managers

began to view quality

positively as a competitive advantage, and

to

address

it in their strategic planning processes,

which are focused on

customer value.

Because

quality started to attract the attention

of top managers, it impacted management

throughout the

organization.

Quality was not just

for the inspectors or people in the

quality assurance department to

worry

about. This era marks the

emergence of a new paradigm

for management. A number of

developments

were brought together and reconfigured

into a new approach to management in

all

departments

and specialties.

A

variety of external forces

brought quality to the attention of

top managers. They began to

see a link

between

losses of profitability and poor

quality. The forces that

brought this connection to

their

37

Total

Quality Management

MGT510

VU

attention

included a rising tide of

multimillion-dollar product liability

suits for defective products

and

constant

pressures from the government on several

fronts, including closer

policing of defects,

product

recalls.

Perhaps the most salient

external force was the

growing market share incursions

from foreign

competitors,

particularly the Japanese, in such

diverse industries as semiconductors,

automobiles,

machine

tools, radial tires, and

consumer electronics.

Producing

products with superior quality,

lower cost, and more reliable

delivery, Japanese firms

gained

market

shares and achieved immense

profitability. The onslaught of

these events in the mid-1970s

and

1980s

seemed rather sudden,

However, Japanese firm had

been building their

industrial capabilities

for

decades,

developing and refining approaches to

quality grounded in the principles

taught to them by

Americans

after World War II. Manager

and theorists have been captivated by

"Japanese management"

over

the last two decades. Indeed, the

Strategic Quality Management era

borrows a number of it

elements

from the developments that quality

took place in Japan at the same

time as the quality

assurance

era in the United

States.

Total

Quality Management

Just

as the definition of quality has

been a source of confusion, so

has the definition of Total

Quality

Management.

There is no consensus on what constitutes

TQM. Almost every

organization defines it

differently

or calls it something other than

TQM.

In

the United States, Total

Quality Management is often

used to refer to the management

approaches

being

developed in the current era of Strategic

Quality Management while the

new paradigm is

emerging.

Ideally, managers in the Strategic

Quality Management era regard

total Quality

management

as

something more than a "program," and

take it beyond all the

deficiencies mentioned

earlier.

In

this context, the word

"Total" conveys the idea that

all employees, throughout every

function and

level

of an organization, pursue quality.

The word "quality" suggests

excellence in every aspect of the

organization.

"Management" refers to the pursuit of

quality results through a

quality management

process.

This begins with strategic management

processes and extends through

product design,

manufacturing,

marketing, finance, and so on. It

encompasses, yet goes

beyond, all of the

earlier

definitions

of quality by puling them together

into a never-ending process of

improvement.

Accordingly,

TQM is as much about the quality

process as it is about quality

results or quality products.

It

began with people,

particularly managers.

38

Table of Contents:

- OVERVIEW OF QUALITY MANAGEMENT:PROFESSIONAL MANAGERIAL ERA (1950)

- TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT AND TOTAL ORGANIZATION EXCELLENCE:Measurement

- INTEGRATING PEOPLE AND PERFORMANCE THROUGH QUALITY MANAGEMENT

- FUNDAMENTALS OF TOTAL QUALITY AND RATERS VIEW:The Concept of Quality

- TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT AND GLOBAL COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE:Customer Focus

- TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT AND PLANNING FOR QUALITY AT OFFICE

- LEADERS IN QUALITY REVOLUTION AND DEFINING FOR QUALITY:User-Based

- TAGUCHI LOSS FUNCTION AND QUALITY MANAGEMENT

- WTO, SHIFTING FOCUS OF CORPORATE CULTURE AND ORGANIZATIONAL MODEL OF MANAGEMENT

- HISTORY OF QUALITY MANAGEMENT PARADIGMS

- DEFINING QUALITY, QUALITY MANAGEMENT AND LINKS WITH PROFITABILITY

- LEARNING ABOUT QUALITY AND APPROACHES FROM QUALITY PHILOSOPHIES

- TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT THEORIES EDWARD DEMING’S SYSTEM OF PROFOUND KNOWLEDGE

- DEMING’S PHILOSOPHY AND 14 POINTS FOR MANAGEMENT:The cost of quality

- DEMING CYCLE AND QUALITY TRILOGY:Juran’s Three Basic Steps to Progress

- JURAN AND CROSBY ON QUALITY AND QUALITY IS FREE:Quality Planning

- CROSBY’S CONCEPT OF COST OF QUALITY:Cost of Quality Attitude

- COSTS OF QUALITY AND RETURN ON QUALITY:Total Quality Costs

- OVERVIEW OF TOTAL QUALITY APPROACHES:The Future of Quality Management

- BUSINESS EXCELLENCE MODELS:Excellence in all functions

- DESIGNING ORGANIZATIONS FOR QUALITY:Customer focus, Leadership

- DEVELOPING ISO QMS FOR CERTIFICATION:Process approach

- ISO 9001(2000) QMS MANAGEMENT RESPONSIBILITY:Issues to be Considered

- ISO 9001(2000) QMS (CLAUSE # 6) RESOURCES MANAGEMENT:Training and Awareness

- ISO 9001(2000) (CLAUSE # 7) PRODUCT REALIZATION AND CUSTOMER RELATED PROCESSES

- ISO 9001(2000) QMS (CLAUSE # 7) CONTROL OF PRODUCTION AND SERVICES

- ISO 9001(2000) QMS (CLAUSE # 8) MEASUREMENT, ANALYSIS, AND IMPROVEMENT

- QUALITY IN SOFTWARE SECTOR AND MATURITY LEVELS:Structure of CMM

- INSTALLING AN ISO -9001 QM SYSTEM:Implementation, Audit and Registration

- CREATING BUSINESS EXCELLENCE:Elements of a Total Quality Culture

- CREATING QUALITY AT STRATEGIC, TACTICAL AND OPERATIONAL LEVEL

- BIG Q AND SMALL q LEADERSHIP FOR QUALITY:The roles of a Quality Leader

- STRATEGIC PLANNING FOR QUALITY AND ADVANCED QUALITY MANAGEMENT TOOLS

- HOSHIN KANRI AND STRATEGIC POLICY DEPLOYMENT:Senior Management

- QUALITY FUNCTION DEPLOYMENT (QFD) AND OTHER TOOLS FOR IMPLEMENTATION

- BASIC SQC IMPROVEMENT TOOLS:TOTAL QUALITY TOOLS DEFINED

- HOW QUALITY IS IMPLEMENTED? A DIALOGUE WITH A QUALITY MANAGER!

- CAUSE AND EFFECT DIAGRAM AND OTHER TOOLS OF QUALITY:Control Charts

- STATISTICAL PROCESS CONTROL (SPC) FOR CONTINUAL QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

- STATISTICAL PROCESS CONTROL….CONTD:Control Charts

- BUILDING QUALITY THROUGH SPC:Types of Data, Defining Process Capability

- AN INTERVIEW SESSION WITH OFFICERS OF A CMMI LEVEL 5 QUALITY IT PAKISTANI COMPANY

- TEAMWORK CULTURE FOR TQM:Steering Committees, Natural Work Teams

- UNDERSTANDING EMPOWERMENT FOR TQ AND CUSTOMER-SUPPLIER RELATIONSHIP

- CSR, INNOVATION, KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AND INTRODUCING LEARNING ORGANIZATION