|

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

LESSON

07

THE

PROJECT MANAGER

(CONTD.)

Broad

Contents

Successful

Project Manager

Role

of Project Manager

Project

Champions

Project

Manager's Power/

Authority

Functional

and Project

Organizations

7.1

Successful

Project Manager:

A

good project management

methodology provides a framework

with repeatable processes,

guidelines,

and techniques to greatly increase the

odds of success, and therefore,

provides value

to

the project and the Project Manager.

However, it should be understood up front

that project

management

is not totally a science,

and there is never a guarantee of

success. Just the fact

that

a

Project Manager is using a

methodology increases the odds of

project success.

Successful

project

management is strongly dependent

on:

�

A

good daily working

relationship between the Project Manager

and those line

managers

who

directly assign resources to

projects.

�

The

ability of functional employees to report

vertically to their line

manager at the same

time

that they report

horizontally to one or more Project

Managers.

These

two items become critical. In the

first item, functional employees

who are assigned to a

Project

Manager still take technical

direction from their line

managers. Second, employees

who

report

to multiple managers will

always favor the managers

who control their purse

strings.

Thus,

most Project Managers appear

always to be at the mercy of the line

managers.

Classical

management has often been

defined as a process in which the

manager does not

necessarily

perform things for himself,

but accomplishes objectives

through others in a

group

situation.

This basic definition also

applies to the Project Manager. In

addition, a Project

Manager

must help himself. There is

nobody else to help

him.

If

we take a close look at

project management, we will

see that the Project Manager

actually

works

for the line managers, not

vice versa. Many executives do

not realize this. They have

a

tendency

to put a halo around the

head of the Project Manager and

give him a bonus at

project

termination,

when, in fact, the credit

should really go to the line

managers, who are

continually

pressured

to make better use of their

resources. The Project

Manager is simply the agent

through

whom this is accomplished. So why do

some companies glorify the

project

management

position?

7.2

Role

of the Project Manager:

A

Project Manager is the person

who has the overall

responsibility for the successful

planning

and

execution of a project. This

title is used in the construction

industry, architecture,

information

technology and many

different occupations that are

based on production of a

product

or service.

The

Project Manager must possess

a combination of skills including an

ability to ask

penetrating

questions, detect unstated assumptions

and resolve interpersonal

conflicts as well as

more

systematic management

skills.

57

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

Key

amongst his/her duties is the recognition

that risk directly impacts

the likelihood of success

and

that this risk must be

both formally and informally

measured throughout the lifetime of

the

project.

Risk

arises primarily from

uncertainty and the successful

Project Manager is the one

who

focuses

upon this as the main concern.

Most of the issues that

impact a project arise in

one way

or

another from risk. A good

Project Manager can reduce

risk significantly, often by

adhering to

a

policy of open communication, ensuring

that every significant

participant has an

opportunity

to

express opinions and

concerns.

It

follows from the above that a

Project Manager is one who is responsible

for making decisions

both

large and small, in such a

way that risk is controlled

and uncertainty minimized.

Every

decision

taken by the Project Manager

should be taken in such a

way that it directly

benefits the

project.

Project

Managers use project

management software, such as

Microsoft Project, to organize

their

tasks

and workforce. These

software packages allow

Project Managers to produce reports

and

charts

in a few minutes, compared to the several hours it

can take if they do not

use a software

package.

7.3

Roles

and Responsibilities of Project

Manager:

The

role of the Project Manager

encompasses many activities

including:

�

Planning

and defining scope

�

Activity

planning and sequencing

�

Resource

planning

�

Developing

schedules

�

Time

estimating

�

Cost

estimating

�

Developing

a budget

�

Controlling

quality

�

Managing

risks and issues

�

Creating

charts and schedules

�

Risk

analysis

�

Benefits

realization

�

Scalability,

interoperability and portability

analysis

�

Documentation

�

Team

leadership

�

Strategic

influencing

�

Customer

liaison

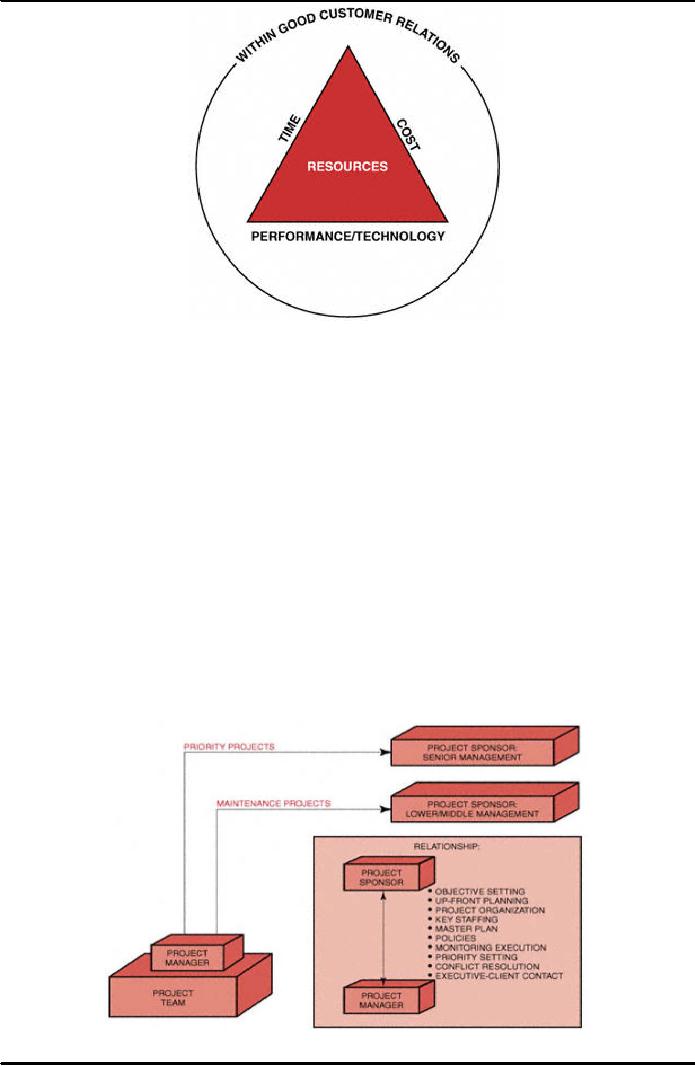

To

illustrate the role of the Project

Manager, consider the time, cost, and

performance

constraints

shown in the Figure 7.1 below.

Many functional managers, if

left alone, would

recognize

only the performance constraint: "Just

give me another $50,000 and

two more

months,

and I will give you the

ideal technology."

The

Project Manager, as part of

these communicating, coordinating, and

integrating

responsibilities,

reminds the line managers that there

are also time and cost

constraints on the

project.

This is the starting point

for better resource

control.

58

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

Figure

7.1: Overview of Project

Management

Success

in project management is like a

three-legged stool. The

first leg is the Project

Manager,

the

second leg is the line manager, and the

third leg is senior management. If

any of the three

legs

fail, then even delicate

balancing may not prevent

the stool from toppling

down.

The

critical node in project management is

the Project ManagerLine Manager

interface. At this

interface,

the project and line managers

must view each other as

equals and be willing to

share

authority,

responsibility, and accountability. In

excellently managed companies,

Project

Managers

do not negotiate for

resources but simply ask

for the line manager's

commitment to

executing

his portion of the work

within time, cost, and

performance. Therefore, in

excellent

companies,

it should not matter who the

line manager assigns as long

as the line manager

lives

up

to his commitments.

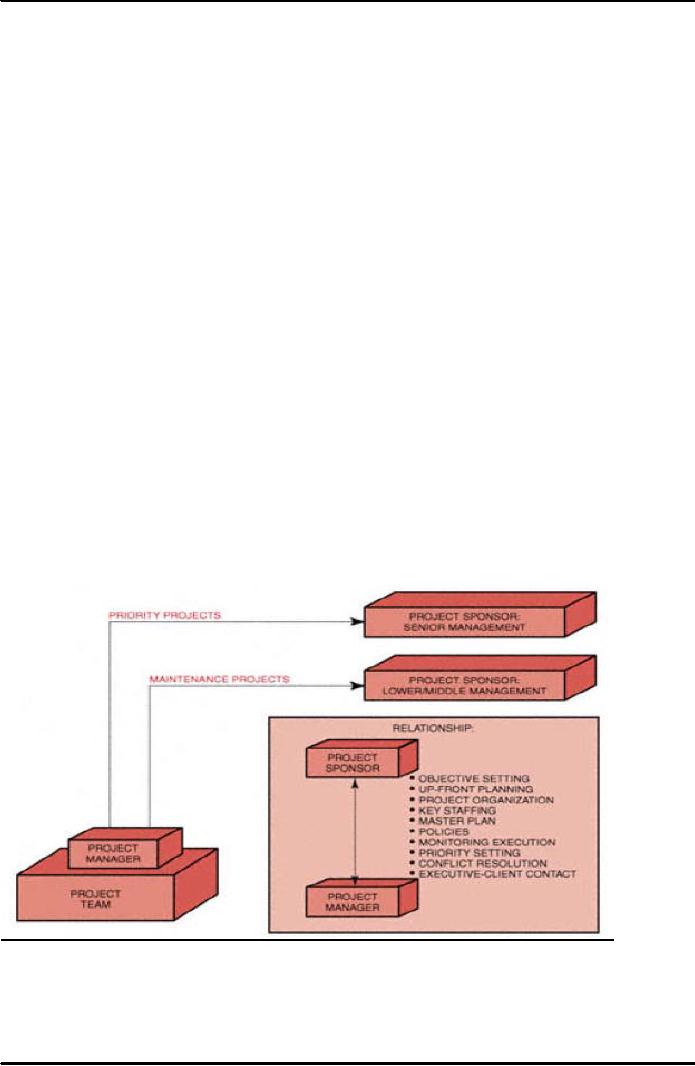

Since

the project and line managers

are "equals," senior management

involvement is necessary

to

provide advice and guidance to the

Project Manager, as well as to

provide encouragement to

the

line managers to keep their

promises. When executives act in

this capacity, they assume

the

role

of project sponsors, as shown in Figure

7.2 below, which also

shows that sponsorship

need

not

always be at the executive levels.

The exact person appointed as the

project sponsor is

based

on

the dollar value of the project, the

priority of the project, and who the

customer is.

Figure

7.2: The project sponsor

interface

59

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

The

ultimate objective of the project

sponsor is to provide behind-the-scenes

assistance to

project

personnel for projects both "internal" to

the company, as well as "external," as

shown in

Figure

7.2 above.

Projects

can still be successful

without this commitment and support, as

long as all work

flows

smoothly.

But in time of crisis, having a

''big brother" available as a possible

sounding board

will

surely help.

When

an executive is required to act as a

project sponsor, then the executive

has the

responsibility

to make effective and timely

project decisions. To accomplish this, the

executive

needs

timely, accurate, and complete data

for such decisions. The

Project Manager must

be

made

to realize that keeping

management informed serves

this purpose, and that the

all-too-

common

practice of "stonewalling" will prevent

an executive from making

effective decisions

related

to the project.

The

line manager has to cope

with:

�

Unlimited

work requests (especially

during competitive

bidding)

�

Predetermined

deadlines

�

All

requests having a high

priority

�

Limited

number of resources

�

Limited

availability of resources

�

Unscheduled

changes in the project

plan

�

Unpredicted

lack of progress

�

Unplanned

absence of resources

�

Unplanned

breakdown of resources

�

Unplanned

loss of resources

�

Unplanned

turnover of personnel

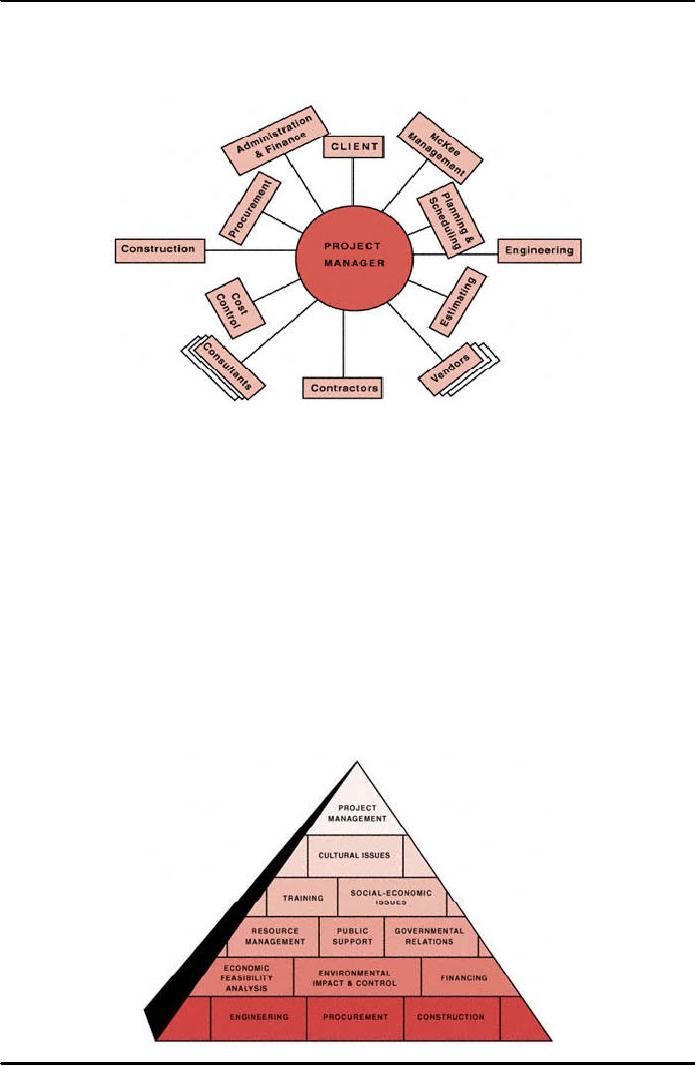

Figure

7.3: Negotiating activities of System

Management

The

difficulty in staffing, especially

for Project Managers or Assistant

Project Managers, is in

determining

what questions to ask during an

interview to see if an individual

has the necessary

or

desired characteristics. There are

numerous situations in which

individuals are qualified to

be

promoted

vertically but not

horizontally. An individual with

poor communication skills

and

60

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

interpersonal

skills can be promoted to a

line management slot because

of his technical

expertise,

but this same individual is

not qualified for project

management promotion.

Figure

7.4: Managing the

Project

Most

executives have found that the best

way to interview is by reading

each element of the job

description

to the potential candidate. Many

individuals want a career

path in project

management

but are totally unaware of

what the Project Manager's duties

are.

So

far we have discussed the personal

characteristics of the Project Manager.

There are also

job

related

questions to consider, such

as:

�

Are

feasibility and economic analyses

necessary?

�

Is

complex technical expertise required? If

so, is it within the individual's

capabilities?

�

If

the individual is lacking expertise, will

there be sufficient backup strength in the

line

organizations?

�

Is

this the company's or the individual's

first exposure to this type of

project and/or client?

If

so,

what are the risks to be

considered?

�

What

is the priority for this

project, and what are the

risks?

�

With

whom must the Project

Manager interface, both

inside and outside the

organization?

61

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

Figure

7.5: Project management

responsibilities

Most

good Project Managers

generally know how to

perform feasibility studies

and cost-benefit

analyses.

Sometimes this capability

can create organizational

conflict. A major utility

company

begins

each computer project with a

feasibility study in which a

cost-benefit analysis is

performed.

The

Project Managers, all of

whom report to a project

management division, perform the

study

themselves

without any direct

functional support. The

functional managers argue that the

results

are

grossly inaccurate because the functional

experts are not involved.

The Project Manager,

on

the

other hand, argues that they

never have sufficient time or

money to perform a complete

analysis.

There

are also good reasons

for recruiting from outside

the company. A new Project

Manager

hired

from the outside would be

less likely to have strong informal ties

to any one line

organization

and thus, could show impartiality on the

project. Some companies

further require

that

the individual spend an apprenticeship

period of twelve to eighteen

months in a line

organization

to find out how the company

functions, to become acquainted with

some of the

people,

and to understand the company's policies and

procedures.

One

of the most important but

often least understood characteristics of

good Project Managers is

their

ability

to understand and know both

themselves and their employees in terms

of strengths and

weaknesses.

7.4

Project

Champions:

Corporations

encourage employees to think up new

ideas that, if approved by the

corporation,

will

generate monetary and non-monetary

rewards for the idea

generator. One such reward

is to

identify

the individual as a "Project

Champion". Unfortunately,

all too often the

Project

Champion

becomes the Project Manager, and,

although the idea was

technically sounds, the

project

fails.

Table

7.1: Project Managers versus Project

Champions

7.5

Power

and Authority of Project

Manager:

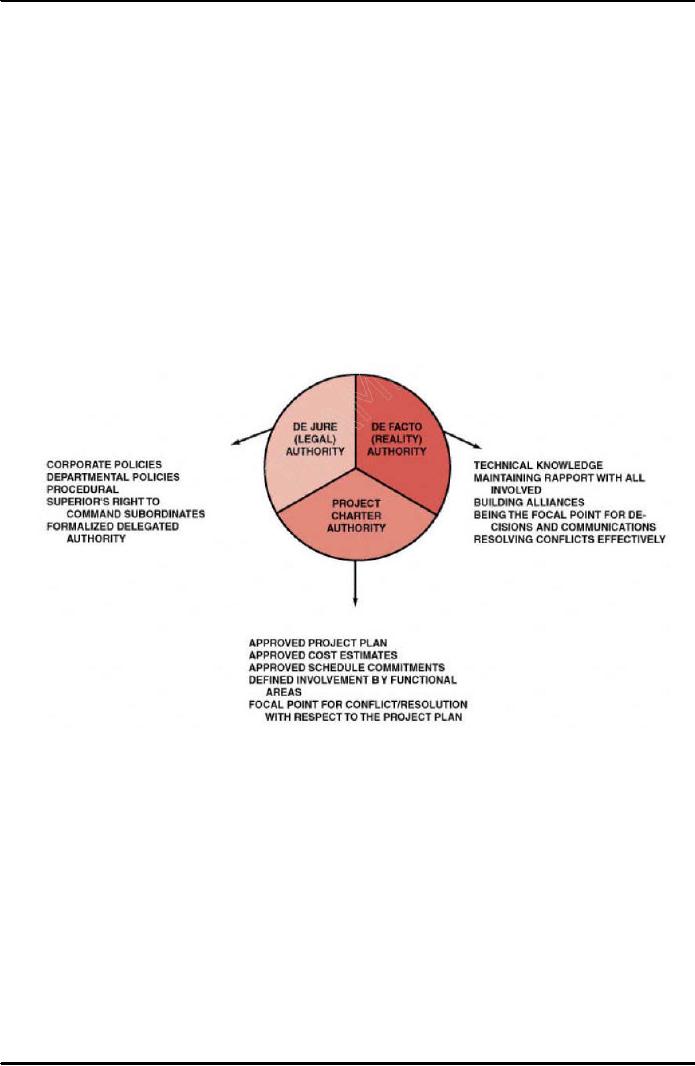

One

form of the Project Manager's

authority can be defined as the

legal or rightful power

to

command,

act, or direct the activities of others.

The breakdown of the Project

Manager's

authority

is shown in Figure 7.6 below.

Authority can be delegated from

one's superiors. Power,

62

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

on

the other hand, is granted to an individual by his

subordinates and is a measure of

their

respect

for him. A manager's

authority is a combination of his

power and influence such

that

subordinates,

peers, and associates willingly

accept his judgment.

In

the traditional structure, the power

spectrum is realized through the

hierarchy, whereas in the

project

structure, power comes from

credibility, expertise, or being a sound

decision-maker.

Authority

is the key to the project management

process. The Project Manager

must manage

across

functional and organizational lines by

bringing together activities

required to accomplish

the

objectives of a specific project.

Project authority provides the

way of thinking required

to

unify

all organizational activities

toward accomplishment of the project

regardless of where

they

are located.

The

Project Manager who fails to

build and maintain his alliances

will soon find opposition

or

indifference

to his project requirements.

The

amount of authority granted to the Project

Manager varies according to project

size,

management

philosophy, and management interpretation

of potential conflicts with

functional

managers.

There do exist, however,

certain fundamental elements

over which the

Project

Manager

must have authority in order to

maintain effective

control.

Figure

7.6: Project Authority

Breakdown

Generally

speaking, a project manager

should have more authority than

his responsibility calls

for,

the exact amount of authority usually

depending on the amount of risk

that the Project

Manager

must take. The greater the

risk, the greater the amount of authority is. A

good Project

Manager

knows where his authority

ends and does not hold an

employee responsible for duties

that

he (the Project Manager)

does not have the authority to enforce.

Some projects are

directed

by

Project Managers who have

only monitoring authority.

These Project Managers are

referred

to

as influence Project

Managers.

Failure

to establish authority relationships can

result in:

�

Poor

communication channels

�

Misleading

information

�

Antagonism,

especially from the informal

organization

�

Poor

working relationships with superiors,

subordinates, peers, and

associates

�

Surprises

for the customer

63

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

The

following are the most common

sources of power and

authority problems in a project

environment:

�

Poorly

documented or no formal authority

�

Power and

authority perceived

incorrectly

�

Dual

accountability of personnel

�

Two

bosses (who often

disagree)

�

The

project organization encouraging

individualism

�

Subordinate

relations stronger than peer or

superior relationships

�

Shifting

of personnel loyalties from vertical to

horizontal lines

�

Group

decision making based on the

strongest group

�

Ability

to influence or administer rewards

and punishment

�

Sharing

resources among several projects

The

project management organizational

structure is an arena of continuous

conflict and

negotiation.

Although there are many

clearly defined authority boundaries

between functional

and

project management responsibilities, the

fact that each project

can be inherently

different

from

all others almost always

creates new areas where

authority negotiations are

necessary.

Certain

ground rules exist for

authority control through

negotiations.

Negotiations

should

take

place at the lowest level of

interaction.

Definition

of the problem must be the first

priority. This should

include:

�

The

issue

�

The

impact

�

The

alternative

�

The

recommendations

Higher-level

authority should be used if,

and only if, agreement cannot be

reached.

7.6

Functional

and Project Organizations:

Functional

organization is structure in which

authority rests with the

functional heads; the

structure

is sectioned by departmental groups.

7.6.1

Advantages

of Functional Structure:

�

Simple

and clear; coordination left to

top management

�

Reduces

overhead

�

Provides

clearly marked career paths

for hiring and

promotion

�

Employees

work alongside colleagues who

share similar

interests

7.6.2

Disadvantages

of Functional Structure:

�

Coordination

of functional tasks is difficult;

little reward for

cooperation with

other

groups

since authority resides with

functional supervisor.

�

Provides

scope for different department

heads to pass-off company project

failures

as

being due to the failures of other

departments.

7.6.3

Matrix

Organizations:

Most

organizations fall somewhere between the

fully functional and fully

projectized

organizational

structure. These are matrix

organizations.

Three points along

the

organizational

continuum have been

defined.

64

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

1.

Weak/Functional

Matrix:

A

Project Manager (often

called a project administrator

under this type of

organization)

with only limited authority

is assigned to oversee the

cross-

functional

aspects of the project. The

functional managers maintain

control over

their

resources and project areas.

The project administrator's

role is to enhance

communication

between functional managers and track

overall project

progress.

2.

Balanced/Functional

Matrix:

A

Project Manager is assigned to

oversee the project. Power is shared

equally

between

the Project Manager and the functional

managers. Proponents of this

structure

believe it strikes the correct balance, bringing

forth the best aspects

of

functional

and projectized organizations.

However, this is the most

difficult

system

to maintain as the sharing of power is a

very delicate proposition.

This

is

also the most complex

organizational structure to

maintain.

3.

Strong/Project

Matrix:

A

Project Manager is primarily responsible

for the project.

Functional

managers

provide technical expertise and assign

resources on an as-needed

basis.

Because project resources

are assigned as necessary, there

can be

conflicts

between the Project Manager and the

functional manager

over

resource

assignment. The functional

manager has to staff

multiple projects with

the

same experts.

4.

Soft

boundaries Matrix:

A

fourth organization type is the

"soft boundaries matrix". In this the

functional

team

members provide technical expertise

and assign resources on an

as-needed

basis.

Because project resources

are assigned as necessary there is no

need for

Project

Managers or a functional manager

over resource

assignment.

65

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Broad Contents, Functions of Management

- CONCEPTS, DEFINITIONS AND NATURE OF PROJECTS:Why Projects are initiated?, Project Participants

- CONCEPTS OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT:THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT SYSTEM, Managerial Skills

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT METHODOLOGIES AND ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES:Systems, Programs, and Projects

- PROJECT LIFE CYCLES:Conceptual Phase, Implementation Phase, Engineering Project

- THE PROJECT MANAGER:Team Building Skills, Conflict Resolution Skills, Organizing

- THE PROJECT MANAGER (CONTD.):Project Champions, Project Authority Breakdown

- PROJECT CONCEPTION AND PROJECT FEASIBILITY:Feasibility Analysis

- PROJECT FEASIBILITY (CONTD.):Scope of Feasibility Analysis, Project Impacts

- PROJECT FEASIBILITY (CONTD.):Operations and Production, Sales and Marketing

- PROJECT SELECTION:Modeling, The Operating Necessity, The Competitive Necessity

- PROJECT SELECTION (CONTD.):Payback Period, Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

- PROJECT PROPOSAL:Preparation for Future Proposal, Proposal Effort

- PROJECT PROPOSAL (CONTD.):Background on the Opportunity, Costs, Resources Required

- PROJECT PLANNING:Planning of Execution, Operations, Installation and Use

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Outside Clients, Quality Control Planning

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Elements of a Project Plan, Potential Problems

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Sorting Out Project, Project Mission, Categories of Planning

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Identifying Strategic Project Variables, Competitive Resources

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Responsibilities of Key Players, Line manager will define

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):The Statement of Work (Sow)

- WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE:Characteristics of Work Package

- WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE:Why Do Plans Fail?

- SCHEDULES AND CHARTS:Master Production Scheduling, Program Plan

- TOTAL PROJECT PLANNING:Management Control, Project Fast-Tracking

- PROJECT SCOPE MANAGEMENT:Why is Scope Important?, Scope Management Plan

- PROJECT SCOPE MANAGEMENT:Project Scope Definition, Scope Change Control

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Historical Evolution of Networks, Dummy Activities

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Slack Time Calculation, Network Re-planning

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Total PERT/CPM Planning, PERT/CPM Problem Areas

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION:GLOBAL PRICING STRATEGIES, TYPES OF ESTIMATES

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.):LABOR DISTRIBUTIONS, OVERHEAD RATES

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.):MATERIALS/SUPPORT COSTS, PRICING OUT THE WORK

- QUALITY IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Value-Based Perspective, Customer-Driven Quality

- QUALITY IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT (CONTD.):Total Quality Management

- PRINCIPLES OF TOTAL QUALITY:EMPOWERMENT, COST OF QUALITY

- CUSTOMER FOCUSED PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Threshold Attributes

- QUALITY IMPROVEMENT TOOLS:Data Tables, Identify the problem, Random method

- PROJECT EFFECTIVENESS THROUGH ENHANCED PRODUCTIVITY:Messages of Productivity, Productivity Improvement

- COST MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL IN PROJECTS:Project benefits, Understanding Control

- COST MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL IN PROJECTS:Variance, Depreciation

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT THROUGH LEADERSHIP:The Tasks of Leadership, The Job of a Leader

- COMMUNICATION IN THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Cost of Correspondence, CHANNEL

- PROJECT RISK MANAGEMENT:Components of Risk, Categories of Risk, Risk Planning

- PROJECT PROCUREMENT, CONTRACT MANAGEMENT, AND ETHICS IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Procurement Cycles