|

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

LESSON

41

COST

MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL IN

PROJECTS

BROAD

CONTENTS

Budget

Variances

& Earned Value

ACWP,

BCWS, BCWP

Cost

& Schedule Variance

CPI,

SPI

Variance

Analysis (V/A)

Depreciation

& Ethics

41.1

Budgets

The

project budget, which is the

final result of the planning

cycle of the MCCS, must be

reasonable,

attainable,

and based on:

�

Contractually

Negotiated Costs And

�

The

Statement of Work.

The

basis for the budget

is:

�

Historical

Cost,

�

Best

Estimates, Or

�

Industrial

Engineering Standards.

The

budget must identify:

�

Planned

Manpower Requirements,

�

Contract

Allocated Funds, And

�

Management

Reserve.

All

budgets must be traceable through the

budget "log," which

includes:

�

Distributed

budget

�

Management

reserve

�

Undistributed

budget

�

Contract

changes

Management

reserve is the dollar amount established by the

project office to budget for

all categories of

unforeseen

problems and contingencies resulting in out-of-scope

work to the performers. Management

reserve

should be used for tasks or

dollars, such as rate changes, and

not to cover up bad

planning

estimates

or budget overruns. When a significant

change occurs in the rate structure, the

total

performance

budget should be adjusted.

In

addition to the "normal" performance

budget and the management reserve

budget, there also exists

the

following: Undistributed budget,

which is that budget

associated with contract changes where

time

constraints

prevent the necessary planning to

incorporate the change into the

performance budget. (This

effort

may be time-constrained.) Unallocated

budget, which represents a

logical grouping of contract

tasks

that have not yet been

identified and/or

authorized.

41.2

Variance

Variance

is defined as any schedule,

technical performance, or cost deviation

from a specific plan.

Variances

are used by all levels of

management to verify the budgeting

system and the scheduling

system.

The budgeting and scheduling

system variance must be

compared together

because:

The

cost variance compares

deviations only from the

budget and does not provide

a measure of

comparison

between work scheduled and work

accomplished.

321

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

The

scheduling variance provides a comparison

between planned and actual performance but

does not

include

costs.

There

are two primary methods of

measurement:

Measurable

efforts: discrete

increments of work with a definable

schedule for accomplishment,

whose

completion

produces tangible

results.

Level

of effort: work

that does not lend

itself to subdivision into

discrete scheduled increments of

work,

such

as project support and project

control.

41.2.1

Variances

are used on both types of

measurement. In order to calculate variances

we

must

define the three basic variances for

budgeting and actual costs for

work scheduled and

performed.

Archibald

defines these

variables:

Budgeted

cost for work scheduled

(BCWS) is the budgeted

amount of cost for work

scheduled to be

accomplished

plus the amount or level of

effort or apportioned effort

scheduled to be accomplished in a

given

time period.

Budget

cost for work performed

(BCWP) is the budgeted

amount of cost for completed

work, plus

budgeted

for level of effort or

apportioned effort activity completed

within a given time period.

This is

sometimes

referred to as "earned

value."

Actual

cost for work performed

(ACWP) is the amount

reported as actually expended in

completing

the

work accomplished within a given

time period.

Planned

Value (PV) What

Plan should be worth at this

point in "Schedule". Also

BCWS: Budgeted

amount

of "Cost for work Schedule"

to be accomplished Plus "Amount or level

of effort for

"Schedule"

to

be Accomplished at a given time

period.

Earned

Value (EV) Physical

work completed to date &

with in authorized "Budget"

for that.

The

budget at completion is the sum of

all budgets (BCWS) allocated

to the project. This is

often

synonymous

with the project baseline. This is

what the total effort should

cost. The estimate at

completion

identifies either the dollars or hours

that represent a realistic appraisal of

the work when

performed.

It is the sum of all direct

and indirect costs to date

plus the estimate of all

authorized work

remaining

(EAC = cumulative actuals + the

estimate-to-complete).

Using

the above definitions, we can calculate the

variance at completion

(VAC):

The

estimate at completion (EAC) is the

best estimate of the total

cost at the completion of the

project.

The

EAC is a periodic evaluation of the

project status, usually on a

monthly basis or until a

significant

change

has been identified. It is

usually the responsibility of the

performing organization to prepare

the

EAC.

These

costs can then be applied to

any level of the work

breakdown structure (i.e., program,

project,

task,

subtask, work package) for

work that is completed, in-program, or

anticipated. Using

these

definitions,

the following variance definitions

are obtained:

Cost

variance (CV)

calculation:

A

negative variance indicates a

cost-overrun condition.

Schedule

variance (SV)

calculation:

A

negative variance indicates a behind-schedule

condition.

In

the analysis of both cost and schedule,

costs are used as the lowest

common denominator. In other

words,

the schedule variance is given as a

function of cost. To alleviate

this problem, the variances

are

usually

converted to percentages:

322

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

The

schedule variance may be

represented by hours, days, weeks, or

even dollars.

As

an example, consider a project that is

scheduled to spend $100K for

each of the first four weeks

of

the

project. The actual expenditures at the

end of week four are $325K.

Therefore, BCWS = $400K

and

ACWP

= $325K. From these two

parameters alone, there are several

possible explanations as to

project

status.

However, if BCWP is now

known, say $300K, and then

the project is behind schedule

and

overrunning

costs.

Variances

are almost always identified as

critical items and are reported to

all organizational

levels.

Critical

variances are established for each

level of the organization in accordance

with management

policies.

Not

all companies have a uniform

methodology for variance thresholds.

Permitted variances may be

dependent

on such factors as:

�

Life-cycle

phase

�

Length

of life-cycle phase

�

Length

of project

�

Type

of estimate

�

Accuracy

of estimate

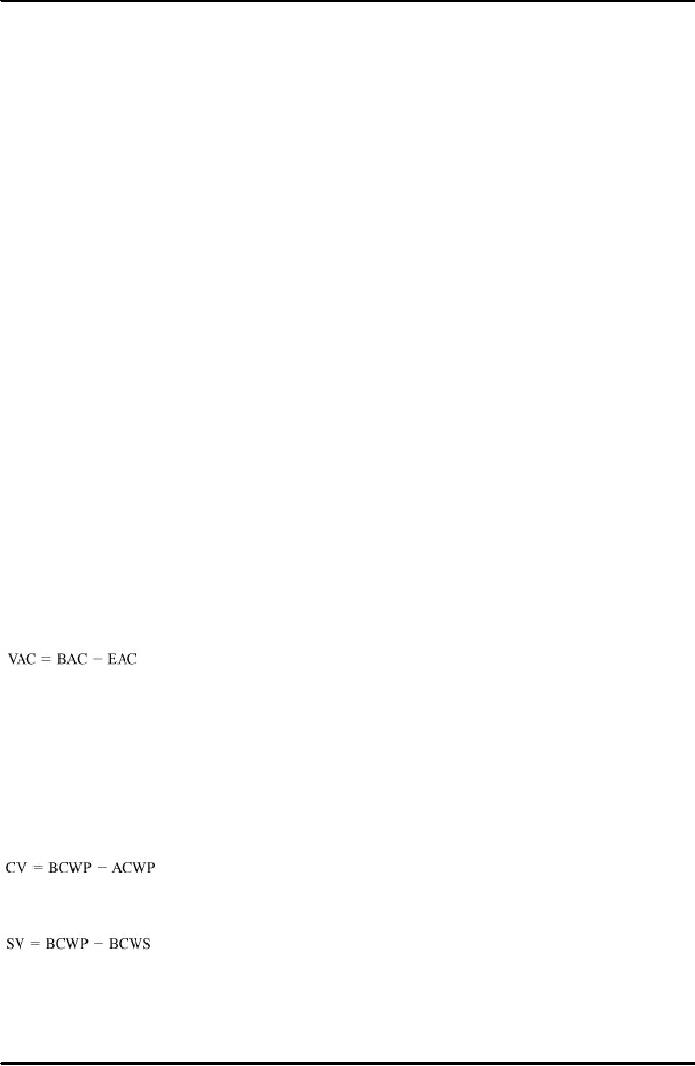

Figure

41.1: Project variance

projections

Figure

41.1 shows time-phased cost variances

for a program requiring

research and development,

qualification,

and production phases. Since the

risk should decrease as time

goes on, the variance

boundaries

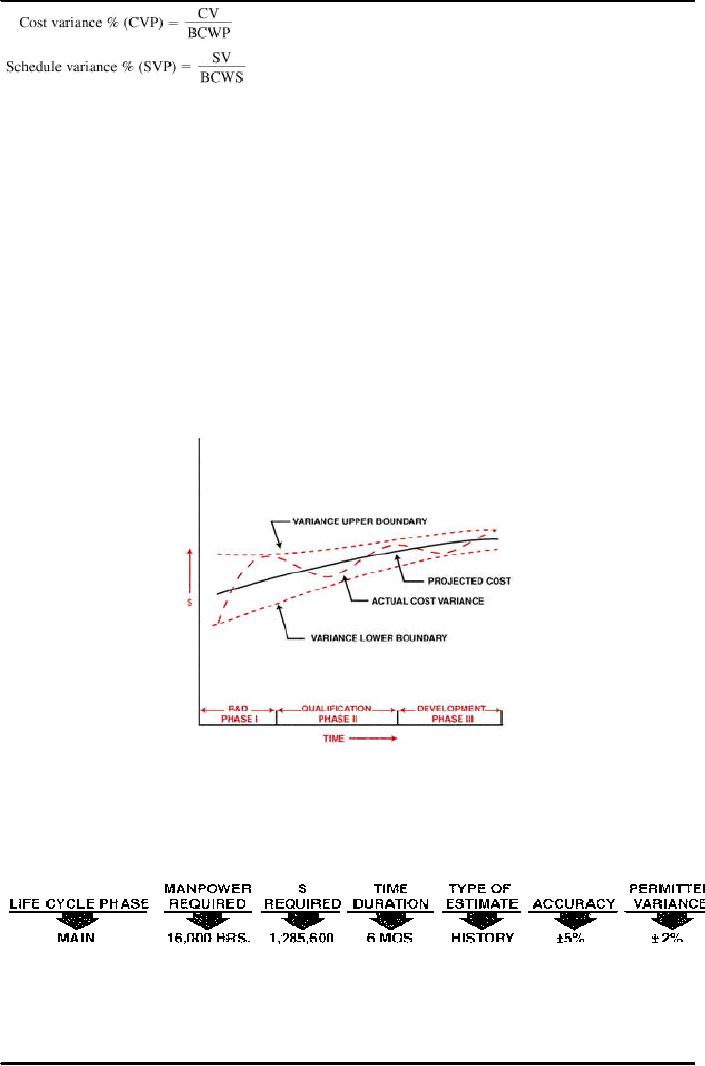

are reduced. Figure 41.2

shows that the variance

envelope in such a case may

be dependent

on

the type of estimate.

Figure

41.2: Methodology to variance

By

using both cost and schedule

variance, we can develop an

integrated cost/schedule reporting

system

that

provides the basis for

variance analysis by measuring cost performance in

relation to work

323

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

accomplished.

This system ensures that

both cost budgeting and performance

scheduling are constructed

on

the same database.

COST

PERFORMANCE INDEX

(CPI)

41.2.2

In

addition to calculating the cost

and schedule variances in terms of

dollars or

percentages,

we also want to know how

efficiently the work has

been accomplished. The formulas

used

to

calculate the performance efficiency as a

percentage of BCWP

are:

If

CPI = 1.0, we have perfect performance.

If CPI > 1.0, we have exceptional

performance. If CPI < 1.0,

we

have poor performance. The same analysis

can be applied to the

SPI.

Variance

Analysis

41.2.3

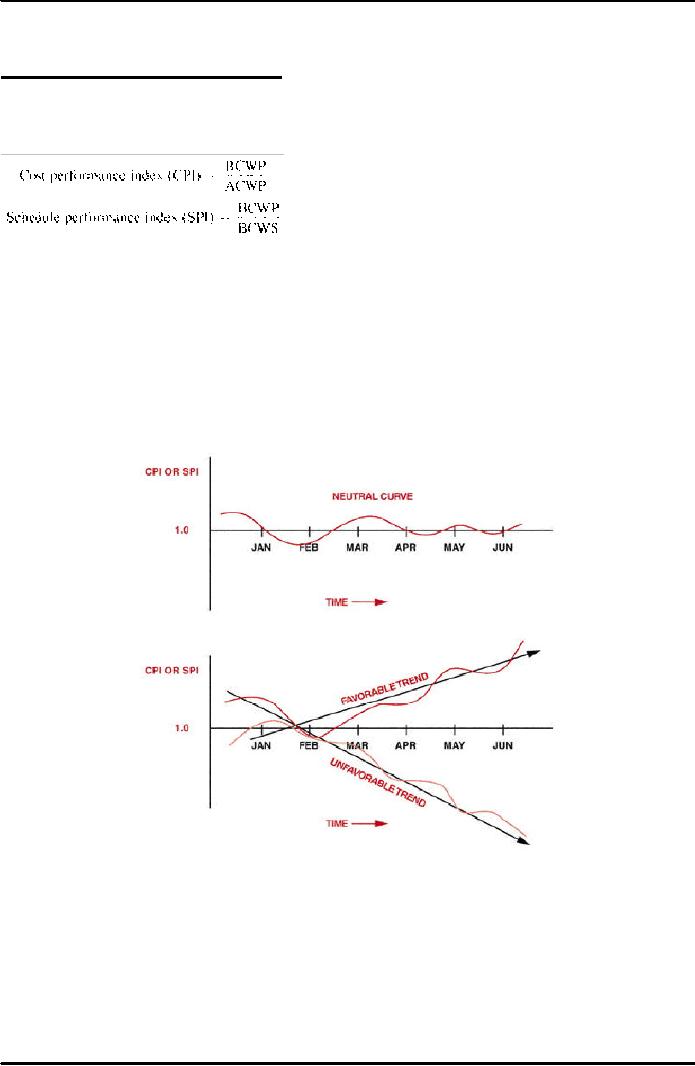

The

cost and schedule performance index is

most often used for

trend analysis as shown

in

Figure 41.3. Companies use

either three-month, four-month, or

six-month moving averages to

predict

trends.

The usefulness of trend analysis is to

take corrective action to

alleviate unfavorable trends

by

having

an early warning system.

Unfortunately, effective use of

trend analysis may be restricted to

long-

term

projects because of the time needed to

correct the situation.

Figure

41.3: The performance

index

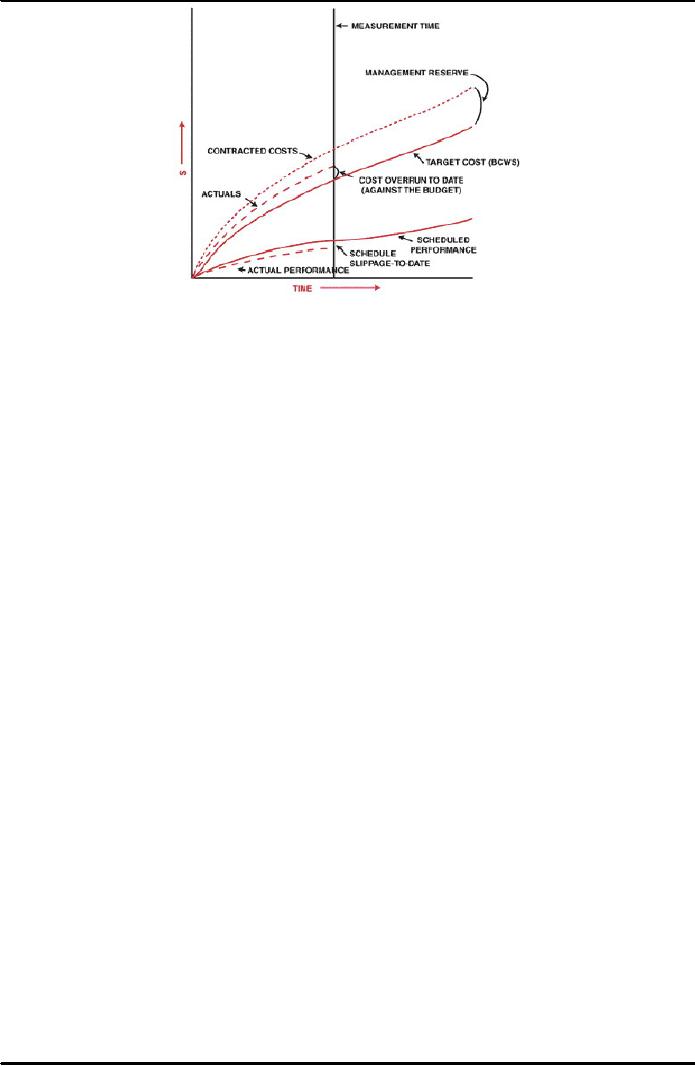

Figure

41.4 shows an integrated

cost/schedule system. The

figure identifies a performance slippage

to

date.

This might not be a bad

situation if the costs are

proportionately under-run. However,

from the

upper

portion of Figure 41.4, we

find that costs are

overrun (in comparison to budget

costs), thus adding

to

the severity of the situation.

324

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

Figure

41.4: Integrated cost/schedule

system

Also

shown in Figure 41.4 is the management

reserve. This is identified as the

difference between the

contracted

cost for projected performance to

date and the budgeted cost. Management

reserves are the

contingency

funds established by the program manager

to counteract unavoidable delays that can

affect

the

project's critical path.

For

variance analysis, goal of cost

account Manager To take

action that will correct

problem within

original

budget or justify a new

estimation.

Five

Questions must be addressed

during variance

analysis:

�

What

is the problem causing the variance?

�

What

is the impact on time, cost, and

performance?

�

What

is the impact on other efforts, if

any?

�

What

corrective action is planned or

under way?

�

What

are the expected results of the

corrective action?

One

of the key parameters used in

variance analysis is the "earned value"

concept, which is the same as

BCWP.

Earned value is a forecasting variable

used to predict whether the

project will finish over

or

under

the budget. As an example, on June 1, the

budget showed that 800 hours

should have been

expended

for a given task. However,

only 600 hours appeared on the

labor report. Therefore,

the

performance

is (800/600) � 100, or 133 percent, and

the task is under running in performance.

If the

actual

hours were 1,000, the performance would be 80 percent,

and an overrun would be

occurring.

The

difficulty in performing variance

analysis is the calculation of BCWP

because one must predict

the

percent

complete. To eliminate this problem,

many companies use standard

dollar expenditures for

the

project,

regardless of percent complete. For

example, we could say that

10 percent of the costs are to be

"booked"

for each 10 percent of the time

interval. Another technique, and

perhaps the most common, is

the

50/50 rule:

50/50

rule

Half

of the budget for each element is

recorded at the time that

the work is scheduled to

begin, and the

other

half at the time that

the work is scheduled to be completed.

For a project with a large

number of

elements,

the amount of distortion from such a

procedure is minimal. 50/50 rule

eliminate the necessity

for

the continuous determination of percent

complete.

41.3

Depreciation

41.3.1

Depreciation

is the technique used to compute

"Estimated value" of any

object after

few

years. Some types

are:

325

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

1.

Straight line depreciation

same amount deprecated (reduced) from

cost each year.

2.

Double-declining balance First

year - high "Deduction in

value" Twice amount of straight

line.

Each

year after that deduction

40% less than previous

year.

3.

Sum of year depreciation If

life - 5 years. Total of 1-5

is 15 first year deduce 5/15

from cost, in 2nd

year

Deduce 4/15, & so

on.

41.3.2

Parametric

Modeling Estimation

This

is the use of mathematical model to make

estimation. Following are the

two types of PME.

Regression

Analysis: Mathematical

model based upon historical

information.

Learning

Curve: Model

based upon principal

Cost/unit describes as more work,

Gets completed.

41.3.3

Analogous

Estimating

Estimation

technique with characteristics

Estimation based on past

Project (historical information)

less

accurate

compared to bottom-up estimation

Top-down approach Takes less

time compared to

bottom-up

estimation

Form of an expert

judgment.

41.3.4

Ethics

Ethics

are standards of right &

wrong that influence

behavior. Right behavior is considered

ethical &

wrong

behavior is considered unethical. Major

concern to both managers &

employee.

A

set of beliefs about right

& wrong principles of conduct

governing an individual or a group

behavior

that

is fair & just, over & above

obedience to laws & regulations

Ethics

guide people in dealings

with stack holders & others, to

determine appropriate actions.

Project

Manager

often must choose between the

conflicting interests of

stakeholders.

326

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Broad Contents, Functions of Management

- CONCEPTS, DEFINITIONS AND NATURE OF PROJECTS:Why Projects are initiated?, Project Participants

- CONCEPTS OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT:THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT SYSTEM, Managerial Skills

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT METHODOLOGIES AND ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES:Systems, Programs, and Projects

- PROJECT LIFE CYCLES:Conceptual Phase, Implementation Phase, Engineering Project

- THE PROJECT MANAGER:Team Building Skills, Conflict Resolution Skills, Organizing

- THE PROJECT MANAGER (CONTD.):Project Champions, Project Authority Breakdown

- PROJECT CONCEPTION AND PROJECT FEASIBILITY:Feasibility Analysis

- PROJECT FEASIBILITY (CONTD.):Scope of Feasibility Analysis, Project Impacts

- PROJECT FEASIBILITY (CONTD.):Operations and Production, Sales and Marketing

- PROJECT SELECTION:Modeling, The Operating Necessity, The Competitive Necessity

- PROJECT SELECTION (CONTD.):Payback Period, Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

- PROJECT PROPOSAL:Preparation for Future Proposal, Proposal Effort

- PROJECT PROPOSAL (CONTD.):Background on the Opportunity, Costs, Resources Required

- PROJECT PLANNING:Planning of Execution, Operations, Installation and Use

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Outside Clients, Quality Control Planning

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Elements of a Project Plan, Potential Problems

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Sorting Out Project, Project Mission, Categories of Planning

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Identifying Strategic Project Variables, Competitive Resources

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Responsibilities of Key Players, Line manager will define

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):The Statement of Work (Sow)

- WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE:Characteristics of Work Package

- WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE:Why Do Plans Fail?

- SCHEDULES AND CHARTS:Master Production Scheduling, Program Plan

- TOTAL PROJECT PLANNING:Management Control, Project Fast-Tracking

- PROJECT SCOPE MANAGEMENT:Why is Scope Important?, Scope Management Plan

- PROJECT SCOPE MANAGEMENT:Project Scope Definition, Scope Change Control

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Historical Evolution of Networks, Dummy Activities

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Slack Time Calculation, Network Re-planning

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Total PERT/CPM Planning, PERT/CPM Problem Areas

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION:GLOBAL PRICING STRATEGIES, TYPES OF ESTIMATES

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.):LABOR DISTRIBUTIONS, OVERHEAD RATES

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.):MATERIALS/SUPPORT COSTS, PRICING OUT THE WORK

- QUALITY IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Value-Based Perspective, Customer-Driven Quality

- QUALITY IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT (CONTD.):Total Quality Management

- PRINCIPLES OF TOTAL QUALITY:EMPOWERMENT, COST OF QUALITY

- CUSTOMER FOCUSED PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Threshold Attributes

- QUALITY IMPROVEMENT TOOLS:Data Tables, Identify the problem, Random method

- PROJECT EFFECTIVENESS THROUGH ENHANCED PRODUCTIVITY:Messages of Productivity, Productivity Improvement

- COST MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL IN PROJECTS:Project benefits, Understanding Control

- COST MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL IN PROJECTS:Variance, Depreciation

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT THROUGH LEADERSHIP:The Tasks of Leadership, The Job of a Leader

- COMMUNICATION IN THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Cost of Correspondence, CHANNEL

- PROJECT RISK MANAGEMENT:Components of Risk, Categories of Risk, Risk Planning

- PROJECT PROCUREMENT, CONTRACT MANAGEMENT, AND ETHICS IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Procurement Cycles