|

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

LESSON

34

QUALITY

IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT

BROAD

CONTENTS

What

is Quality?

Quality

from Different Perspective

Quality

Dimensions

Competitive

Advantage

Quality

Evolution and Quality Stages in Japan

TQM

(Total Quality Management) and Its Philosophy

34.1

WHAT

IS QUALITY?

Quality

is by no menus a new concept in modern

business. In October 1887, William

Cooper

Procter,

grandson of the founder of Procter

and Gamble, told his employees,

"The first job we

have

is to him out quality

merchandise that consumers

will buy and keep on buying.

If we

produce

it efficiently and economically, we

will earn a profit, in which

you will share."

Procter's

statement

addresses three issues t h a t

are critical to managers of

manufacturing and

service

organizations:

p r o d u c t i v i t y , cost, and

quality. Productivity (the measure of

efficiency defined as

the

amount of output achieved per

unit of input), the cost of

operations, and the quality of

the

goods

and services t h a t create

customer sa t is fa c ti o n all

contribute to profitability. Of these

three

determinants

of p r o f i t a b i li t y , t h e most s i g n i f i c a n t

factor in d e t e r m i n i n g the

long-run

success

or f a i l u r e of any organization is q u a l i t y

. High q u a l i t y goods and

services can

provide

an o r g a n i z a t i o n w i t h a c o m p e t i t i v e edge.

High q u a l i t y reduces costs due

to

returns,

rework, and scrap. It increases p r o d u

c t i v i t y , p r o f i t s , a n d o t h e r measures

of

success.

Most i m p o r t a n t l y , h ig h q u a l i t y

generates s a t i s f i e d customers,

who reward the

organ

i z a t i o n w i t h c o n t i n u e d patronage and

word-of-mouth advertising.

Quality

can be a confusing concept, p a r t l y

because people view q u a l i t y in

relation to

d

i f f e r i n g criteria based on their i

n d i v i d u a l roles in the

production-marketing value

chain.

In addition, the meaning of q u a l i t y continues to

evolve as the quality profession

grows

and matures. Neither

consultants nor business professionals

agree on a universal

definition.

A study t h a t asked managers of 86 f i r m s in

the eastern United States to

define

q

u a l i t y produced several dozen

different responses, including

the following:

1.

Perfection

2.

Consistency

3.

Eliminating

waste

4.

Speed

of delivery

5.

Compliance

w i t h policies and

procedures

6.

Providing

a good, usable

product

7.

Doing

it right the first

time

8.

Delighting

or pleasing customers

9.

Total

customer service and

satisfaction

Thus,

it is important to understand the

various perspectives from

which q u a l i t y is

viewed

in order to f u l l y appreciate the

role it plays in the many p

a i l s of a business

organization.

The

concept of quality is subjective and difficult to define. While certain aspects

of quality can

be

identified, ultimately, the "judgement of quality" rests with the

customer.

248

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

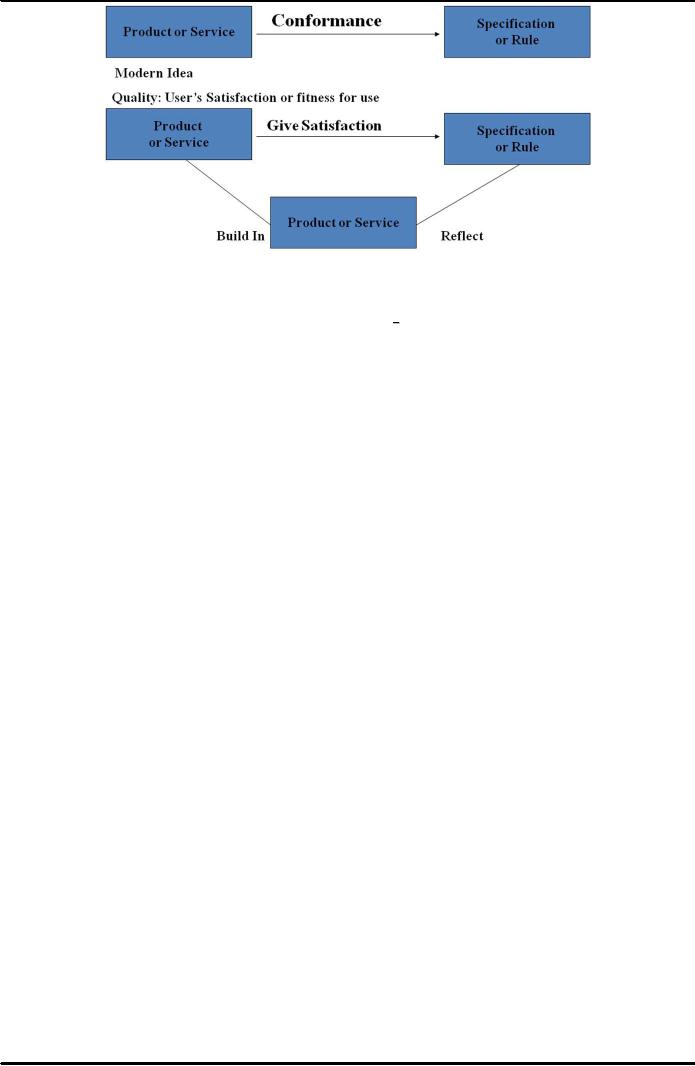

Figure

34.1

QUALITY

FROM DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES:

34.2

�

J

u d g m e n t a l Perspective:

One

common notion of q u a l i t y, used by

consumers, is t h a t it is synonymous wit h

superiority

or excellence. In 1931 Walter

Shewhart f i r s t defined q u a l i t y as t h e

goodness

of

a product. This v i e w is referred to as

the transcended

(to

rise above or extend notably

beyond

ordinary lim its),

d

e f i n i t i o n of quality. In this

sense, q u a l it y is "both

absolute

and

u n i v e r s a l l y recognizable, a mark of

uncompromising standards and

high

achievem

e n t." As such, it cannot he defined

precisely--you j u s t know it when

you see

i

t . It is o f t e n loosely related to a

comparison of f e a t u r e s and

characteristics of products

and

promulgated by m a r k e t i n g e f f o r t s aimed at

developing q u a l i t y as an

image

v

a r i a b l e in the minds of consumers.

Common examples of products a t t r i b uted w i t

h

t

h i s image are Kolex

watches and BMW and Lexus

automobiles.

�

Product-Based

Perspective:

Another

definition of q u a l i t y is t h a t it is a f u n c t i o n of a

specific, measurable variable

and

t

h a t differences in q u a l i t y reflect

differences in q u a n t i t y of product a t t r i b

u t e , such as

in

the number of stitches per i n c h on a s h i r t or in the number

of cy linders in an engine.

This

assessment i m p l i e s t h a t higher

levels or amounts of product

characteristics are

equivalent

to higher quality, As a result,

quality is o f t en mistakenly assumed to

be

related

to price: t h e higher t h e price, the

higher the quality. J u s t consider t h

e case of a

F

l o r i d a man who purchased a

$262,000 Lamborghini o n l y to find a

leaky roof, a b a t t e r y

t

h a t q u i t w i t h o u t notice, a sunroof t h a t

detached when the car

hit a bump, and doors t h a

t

jammed

" However, a product refer to

either a m a n u f a c t u r e d good or a

service--need not

be

expensive to be considered a q u a l i t y product by

consumers. Also, as w i t h t he n o t io n

of

excellence,

the assessment of product a t t r i b u t e s

may v a r y considerably among

individuals.

�

User-Based

Perspective:

A

third definition of q u a l i t y is

based on the presumption t h a t q u a l

i t y is determined by

what

a customer wants. I n d i v i d u a l s

have d i f f e r e n t wants and

needs and, hence, d i f

ferent

quality

standards, which leads to a user-based

definition: q u a l i t y is defined a s f i t n e s s f o

r

intended

use, or

how well t h e product

performs its intended

function. Both a

Cadillac

sedan

and a Jeep Cherokee arc f i t

for use, for example, but

they serve different needs

and

d

i f f e r e n t groups of customers. If

you want a highway-touring

vehicle w i t h lu xu r y

amenities,

then a C a di ll a c may b e t t e r s a t i s f y

your needs. If you want a

vehicle for

camping,

fishing, or skiing trips, a

Jeep might be viewed as h a v i n g

better quality.

249

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

�

Value-Based

Perspective:

A

fourth approach to d e f i n i n g q u a l i t y is

based on value;

t

h a t is, the relationship of

usefulness

or satisfaction to price. From

this perspective, a q u a l i t y product is one

that is

as

useful as competing products

and is sold at a lower

price, or one that offers

greater

usefulness

or s a t i s f a c t i o n at a comparable p r i c e .

Thus, one might purchase a

generic

product,

rather t h a n a brand name

one, if it performs as well as

the brand-name

product

at a lower price. An example of t h i s

perspective in practice is evident in

a

comparison

of t h e U.S. and Japanese a u t o m o b

i l e markets. A Chrysler

marketing

executive

noted "one of t h e main

reasons t h a t t h e l o a d i n g Japanese

brands--Toyota

and

Honda--don't offer t h e huge

incentives of t h e big Three

(General Motors,

Ford,

and

Chrysler) is t h a t they have a

much better reput ation

for long-term durability."

In

essence,

incentives and rebates are payments to

customers lo compensate for

lower

quality.

�

Manufacturing-Based

Perspective:

A

f i f t h view of q u a l i t y is manufacturing-based and d e f i n e s q u a l

i t y as the desirable

outcome

of engineering and m a n u f a c t u r i n g practice,

or conformance

to specifications.

S

p e c i f i c a t i o n s are t a r g e t s and

tolerances determined by designers of

products and

services.

Targets are t h e ideal

values for w hi c h production is to

strive; tolerances

are

specified

because designer's recognize t h a t it

is impossible to meet targets a l l of

the

t

i m e in manufacturing. For example, a

part dimension might be

specified as "0.236 i

0.003

cm." These measurements would mean t h a t t h e t a r

g e t , or ideal value, is

0.236

centimeters,

and t h a t the allowable v a r i a t i o

n is (MHB centimeters from the target

(a

tolerance

of 0.006 cm.). Thus, any

dimension in t h e range 0.233 to

0.239 centimeters is

deemed

acceptable and is said to

conform lo s p e c i f i c a t i o n s . Likewise, in

services,

"on-time

a r r i v a l " for an a i r p l a n e might be

specified as w i t h i n ' 15 minutes of th

e

scheduled

a r r i v a l time. The target is

the scheduled time, and the

tolerance is specified

to

be 15 minutes.

�

Integrating

Perspectives on Quality:

Although

product q u a l i t y should be important

to a ll i n d i v i d u a l s throughout the

value

chain,

how q u a l i t y is viewed may depend on

one's p o s itio n in the v a l u e

chain, that is,

whether

one is t h e designer, manufacturer or s

erv i ce provider, distributor,

or

customer.

The customer is the driving

force for the production of

goods and services,

and

customers generally v i e w quality from

either the transcendent or

the product-

based

perspective. The goods and

services produced should

meet customers'

needs;

indeed,

business organizations' existences depend

upon meeting customer needs. It

is

the

rule of the marketing

function to determine these needs. A

product that meets

customer

needs can rightly be described as a

quality product. Hence, the

user-based

definition

of quality is meaningful to people

who work in

marketing.

The

manufacturer must t r a n s l a t e

customer requirements into

detailed product and

process

specifications. Making this

translation is the role of research

and devel-

opment,

product design, and

engineering. Product specifications

might address such

attributes

as size, form, finish, t as t e ,

dimensions, tolerances, materials,

operational

characteristics,

and s a f e t y featu res .

Process specifications indicate

the types of

equipment,

tools, and facilities to be

used in production. Product

designers must

balance

performance and cost to meet

marketing objectives; thus,

the value-based

definition

of quality is most useful at

this stage.

�

Customer-Driven

Quality:

I

The

American National Standards I n s t i t u

t e ( A N SI ) and the American

Society for

Quality

(ASQ) standardized official

definitions of q u a l i t y terminology in

1978. These

groups

defined q u a l i t y as the

t o t a l i t y of f e a t u r e s a n d characteristics of a

product or

service

t h a t bears on its a b i l i t y to

sati sfy given

needs.

This d e f i n i ti o n draws

heavily

250

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

on

t h e product- and user-based approaches

and is d r i v e n by t h e need to

contribute

v

a l u e to customers and t h u s to

influence s a t i s f a c t i o n and

preference. By the end of

the

1980s,

many companies had begun u s i n g a s i m p l e r ,

yet powerful,

customer-driven

d

e f i n i t i o n of q u a l i t y t h a t remains

popular today:

"

Q u a l i t y is meeting or exceeding

customer expectations"

34.3

QUALITY

DIMENSIONS:

Following

are the "principal quality dimensions":

�

Performance

a product's

primary operating characteristics. For example: A car's

acceleration,

braking distance, steering and handling.

�

Features

the "bells and whistles" of a product. A car may have power options, a

tape or

CD

(compact disk) player, antilock brakes, reclining seats.

�

Reliability

the probability of a product's surviving over a specified period of time

under

stated

"conditions of use". Examples of reliability factors could be a car's ability to

start on

cold

days and frequency of failures.

�

Conformance

the degree to which physical and performance characteristics of a

product

match

with the pre-established standards. For example, car's fit/finish, freedom from

noises

can

reflect this.

�

Durability

the amount of use one gets from a product before it physically

deteriorates or

until

replacement is preferable. If we take the example of a car its corrosion

resistance and

long

wear of upholstery fabric reflects this.

�

Serviceability

this refers to the speed, courtesy, competence of repair work. Auto

owner

access

to spare parts also comes under serviceability.

�

Aesthetics

refers to how a product looks, feels, sounds, tastes, or smells. Car's

color,

instrument

panel design and "feel of road" make it aesthetically

pleasing.

�

Perceived

quality the "subjective assessment of quality" resulting from image.

For

example:

Advertising, or brand names. car, shaped by magazine

reviews-manufacturers'

brochures.

�

Affordability,

Variety, simplicity etc. are also the principal quality

dimensions.

34.4

COMPETITIVE

ADVANTAGE:

When

a firm sustains profits that

exceed the average for its

industry, the firm is said to

possess a

competitive

advantage over

its rivals. The goal of

much of business strategy is to achieve

a

sustainable

competitive advantage.

Michael

Porter identified two basic types of

competitive advantage:

�

Cost

advantage

�

Differentiation

advantage

A

competitive advantage exists when the

firm is able to deliver the

same benefits as competitors

but

at a lower cost (cost advantage), or

deliver benefits that exceed

those of competing products

(differentiation

advantage). Thus, a competitive advantage enables the

firm to create

superior

value

for its customers and

superior profits for

itself.

Cost

and differentiation advantages are

known as positional

advantages since

they describe the

firm's

position in the industry as a leader in

either cost or

differentiation.

A

resource-based

view emphasizes

that a firm utilizes its

resources and capabilities to create

a

competitive

advantage that ultimately results in

superior value

creation.

251

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

QUALITY

EVOLUTION AND QUALITY STAGES IN JAPAN:

34.5

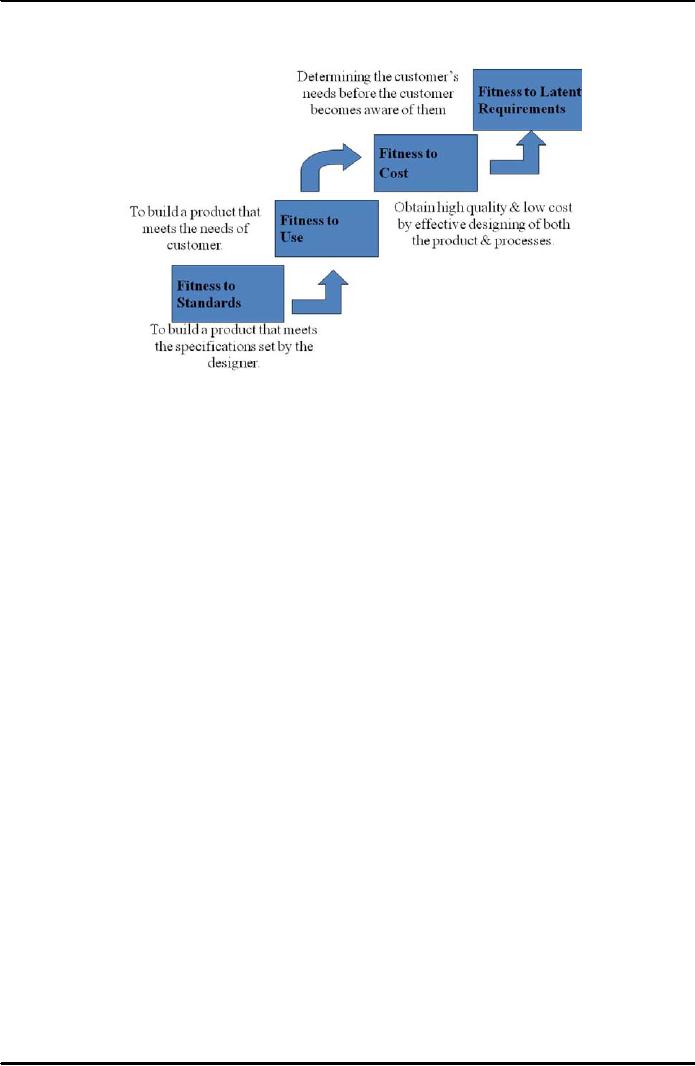

Figure

34.2: Quality

Evolution and Quality Stages in

Japan

34.6

TOTAL

QUALITY MANAGEMENT (TQM) AND ITS PHILOSOPHY:

34.6.1

Quality

as a Management Framework:

In

the 1970s a General Electric

(GE) task force studied

consumer perceptions of

the

quality of various GE product

lines. Lines with relatively

poor reputations

for

quality were found to

deemphasize customer's viewpoint,

regard quality as

synonymous

with tolerance and conformance to

specifications, tic

quality

objectives

to manufacturing flow, express q u ali ty

objectives as the number

of

defects

per unit, and use

formal quality control

systems only in manufacturing.

In

contrast,

product lines that received

customer praise were found

to emphasize

s

ati s fy i n g customer expectations,

determine customer needs

through market

research,

use customer-based quality

performance measures, and have

formalized

quality

control systems in place for

all business functions, not

just for

manufacturing.

The task force concluded

that quality must not be

viewed solely

as

a technical discipline, but

rather as a management discipline.

That is, quality

issues

permeate all aspects of

business enterprise: design,

marketing,

manufacturing,

human resource management,

supplier relations, and

financial

management,

to name just a few.

As

companies came to recognize

the broad scope of quality,

the concept of total

quality

(TQ) emerged. A definition of

total quality was endorsee! In

1992 by the

chairs

and CUOs of nine major

U.S. corporations in cooperation w ith

deans of

business

and engineering departments of

major universities, and

recognized

consultants:

Total

Quality (TQ) is a people-focused

management system that aims

at

continual

increase in customer satisfaction at

continually lower real cost.

TQ

is

a total system approach (not

a separate area or program)

and an integral

pan

of high-level strategy; it works

horizontally across functions

and

departments,

involves all employees, top to bottom,

and extends backward

and

forward

to include the supply chain

and the customer chain. TQ

stresses

learning

and adaptation to continual

change as keys to

organizational

success.

252

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

The

foundation of total quality is

philosophical: the scientific

method. TQ

includes

systems, methods, and tools.

The systems permit change,

the

philosophy

stays the same. TQ is

anchored in values t h a t stress

the

dignity

of the individual and t h e

power of community

action.

Procter

and Gamble uses a concise

definition: Total quality is the

unyielding

and

continually improving effort by everyone

in an organization to

understand,

meet, and exceed the

expectations of customers.

Actually,

the concept of TQ has been

around for some time. A. V.

Feigenbaum

recognized

the importance of a comprehensive

approach to quality in the

1950s

and

coined the term Total q u a l i t y

control. Feigenbaum observed t ha t

the

quality

of products and services is directly

influenced by what he terms

the 9

Ms:

markets, money, management,

men and women, motivation,

materials,

machines

and mechanization, modern

information methods, and

mounting

product

requirements. Although he developed his

ideas from an engineering

perspective,

his concepts apply more

broadly to general

management.

The

Japanese adopted Feigenbaum's

concept and renamed it

companywide

quality

control. Wayne S. Keiker

listed five aspects of total

quality control

practiced

in Japan:

1.

Quality emphasis extends

through market analysis,

design, and customer

service

rather than only the

production stages of making a

product.

2.

Quality emphasis is directed

toward operations in every

department from

executives

to clerical personnel.

3.

Quality is the responsibility of live

individual and the work

group, not

sonic

other group, such as

inspection.

4.

The two types of q u ali t y

characteristics as viewed by customers

are those

that

s at i sf y and those t h at motivate.

Only the l a t t e r are

strongly related to

repeat

sales and a "quality"

image.

5.

The first customer for a

part or piece of information is

usually the next

department

in the production

process.

The

term t

o t a l q u a l i t y m a n a g e m e n t was

developed by the Naval A i r

Systems

Command

to describe its Japanese-style

approach to q u a l i t y improvement

and

became

popular with businesses in the United S t

a t e s during the 1980s. As

we

noted

earlier, TQM has fallen out

of favor, and many people

simply use TQ.

34.6.2

Principles of Total Quality:

Whatever

the language, t o t a l quality is

based on three

fundamental

principles:

1.

A focus on customers and

stakeholders.

2.

Participation and teamwork by

everyone in the

organization.

3.

A process focus supported by

continuous improvement and

learning.

Despite

their obvious simplicity,

these principles are quite

different from

traditional

management practices. Historically,

companies did little to

understand

external customer requirements,

much less those of

internal

customers.

Managers and specialists

controlled and directed

production

systems;

workers told what to do and

how to do it, and rarely

were asked for

their

input. Teamwork was virtua lly

nonexistent. As certain amount of

waste

and

error was tolerable and

was controlled by postproduction

inspection.

Improvements

in quality generally resulted

from technological breakthroughs

instead

of

a relentless mindset of continuous

improvement. With total

quality, an

organization

actively seeks to identify customer

needs and expectations, to

build

quality

into work processes by

tapping the knowledge and

experience of its

workforce/

and to continually improve

every facet of the

organization.

253

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

Customer

and Stakeholder Focus the

customer is the principal judge of

quality. Per-

ceptions

of value and sa ti sf a c t io n are

influenced by many f a c t o r s throughout the

cus-

tomer's

overall purchase, ownership, and

service experiences. To accomplish

this

task,

a company's e f f o r t s need to extend

well beyond merely meeting

specifications,

reducing

defects and errors, or resolving

complaints. They must include

both

designing

new products t h a t tru ly

delight the customer and

responding rapidly to

changing

consumer and market demands. A company

close to its customer knows

what

the customer wants, how the customer

uses its products, and

anticipates needs

t

h a t the customer may not

even be able to express. It

also continually develops

new

ways

of enhancing customer relationships. A

firm also must recognize

that internal

customers

are as important in assuring quality as

are external customers who

purchase

the

product. Employees who view

themselves as both

customers

of

and

suppliers

to other employees understand

how their work links to

the final

product.

After all, the

responsibility of any supplier is to

understand and meet

customer

requirements in the most

efficient and e f f e c t i v e way

possible.

Customer

focus ex te n d s beyond the consumer

and internal customer

relationships,

however.

Employees and so ciety represent

important stakeholders. An

organi-

zation's

success depends on the knowledge,

skills, creativity, and

motivation of its

employees

and partners. Therefore, a TQ

organization must demonstrate

commit-

ment

to employees, provide opportunities

for development and growth,

provide

recognition

beyond normal compensation

systems, share knowledge,

and encourage

risk

taking. Viewing so ciety as a

stakeholder is an a t t r i b u t e of a

world-class

organization.

Bus-mess ethics, public

health and safety, the

environment, and

community

and professional support are necessary a

c t i v i t i e s th a t fall under social

responsibility.

Participation

and Teamwork Joseph Juran credited

Japanese managers' full use

of the

knowledge

and c r e a t i v i t y of the entire

workforce as one of the

reasons for Japan's

rapid

quality achievements. When

managers give employees the

tools to make good

decisions

and the freedom and

encouragement to make contributions,

they virtually

guarantee

that b e t t e r quality products

and production processes

will result.

Employees

who are allowed to

participate--both individually and in

teams--in

decisions

that affect their jobs and

customer can make

substantial contributions to

quality.

His attitude represents a profound

shift in the typical

philosophy of senior

management;

the traditional view was

that the workforce should be

"managed"--or

to

put it less formally, the

workforce should leave their

brains at the door.

Good

intentions

alone are not enough to

encourage employee involvement.

Management's

task

includes formulating the

systems and procedures and

then putting them in

place

to

ensure that participation

becomes a part of the

culture.

254

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Broad Contents, Functions of Management

- CONCEPTS, DEFINITIONS AND NATURE OF PROJECTS:Why Projects are initiated?, Project Participants

- CONCEPTS OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT:THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT SYSTEM, Managerial Skills

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT METHODOLOGIES AND ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES:Systems, Programs, and Projects

- PROJECT LIFE CYCLES:Conceptual Phase, Implementation Phase, Engineering Project

- THE PROJECT MANAGER:Team Building Skills, Conflict Resolution Skills, Organizing

- THE PROJECT MANAGER (CONTD.):Project Champions, Project Authority Breakdown

- PROJECT CONCEPTION AND PROJECT FEASIBILITY:Feasibility Analysis

- PROJECT FEASIBILITY (CONTD.):Scope of Feasibility Analysis, Project Impacts

- PROJECT FEASIBILITY (CONTD.):Operations and Production, Sales and Marketing

- PROJECT SELECTION:Modeling, The Operating Necessity, The Competitive Necessity

- PROJECT SELECTION (CONTD.):Payback Period, Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

- PROJECT PROPOSAL:Preparation for Future Proposal, Proposal Effort

- PROJECT PROPOSAL (CONTD.):Background on the Opportunity, Costs, Resources Required

- PROJECT PLANNING:Planning of Execution, Operations, Installation and Use

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Outside Clients, Quality Control Planning

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Elements of a Project Plan, Potential Problems

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Sorting Out Project, Project Mission, Categories of Planning

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Identifying Strategic Project Variables, Competitive Resources

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Responsibilities of Key Players, Line manager will define

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):The Statement of Work (Sow)

- WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE:Characteristics of Work Package

- WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE:Why Do Plans Fail?

- SCHEDULES AND CHARTS:Master Production Scheduling, Program Plan

- TOTAL PROJECT PLANNING:Management Control, Project Fast-Tracking

- PROJECT SCOPE MANAGEMENT:Why is Scope Important?, Scope Management Plan

- PROJECT SCOPE MANAGEMENT:Project Scope Definition, Scope Change Control

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Historical Evolution of Networks, Dummy Activities

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Slack Time Calculation, Network Re-planning

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Total PERT/CPM Planning, PERT/CPM Problem Areas

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION:GLOBAL PRICING STRATEGIES, TYPES OF ESTIMATES

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.):LABOR DISTRIBUTIONS, OVERHEAD RATES

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.):MATERIALS/SUPPORT COSTS, PRICING OUT THE WORK

- QUALITY IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Value-Based Perspective, Customer-Driven Quality

- QUALITY IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT (CONTD.):Total Quality Management

- PRINCIPLES OF TOTAL QUALITY:EMPOWERMENT, COST OF QUALITY

- CUSTOMER FOCUSED PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Threshold Attributes

- QUALITY IMPROVEMENT TOOLS:Data Tables, Identify the problem, Random method

- PROJECT EFFECTIVENESS THROUGH ENHANCED PRODUCTIVITY:Messages of Productivity, Productivity Improvement

- COST MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL IN PROJECTS:Project benefits, Understanding Control

- COST MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL IN PROJECTS:Variance, Depreciation

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT THROUGH LEADERSHIP:The Tasks of Leadership, The Job of a Leader

- COMMUNICATION IN THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Cost of Correspondence, CHANNEL

- PROJECT RISK MANAGEMENT:Components of Risk, Categories of Risk, Risk Planning

- PROJECT PROCUREMENT, CONTRACT MANAGEMENT, AND ETHICS IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Procurement Cycles