|

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

LESSON

31

PRICING

AND ESTIMATION

BROAD

CONTENTS

Computerized

Software Packages

Pricing

and Estimating

Global

Pricing Strategies

Types

of Estimates

Pricing

Process

31.1

COMPUTERIZED

SOFTWARE PACKAGES:

It

has been seen that

over the past ten years

there has been an explosion in

project management

software

packages. Small packages may

sell for a few thousand

dollars, whereas the price

for

larger

packages may be

$70,000.

Computerized

project management can

provide answers to such questions

as:

�

How

will the project be affected by

limited resources?

�

How

will the project be affected by a

change in the requirements?

�

What

is the cash flow for the

project (and for each

WBS element)?

�

What

is the impact of overtime?

�

What

additional resources are

needed to meet the constraints of the

project?

�

How

will a change in the priority of a

certain WBS element affect the

total project?

The

more sophisticated packages can provide

answers to schedule and cost

based on:

�

Adverse

weather conditions

�

Weekend

activities

�

Unleveled

manpower requirements

�

Variable

crew size

�

Splitting

of activities

�

Assignment

of unused resources

Regardless

of the sophistication of computer systems,

printers and plotters prefer to

draw

straight

lines rather than circles. Most

software systems today use

precedence networks, as

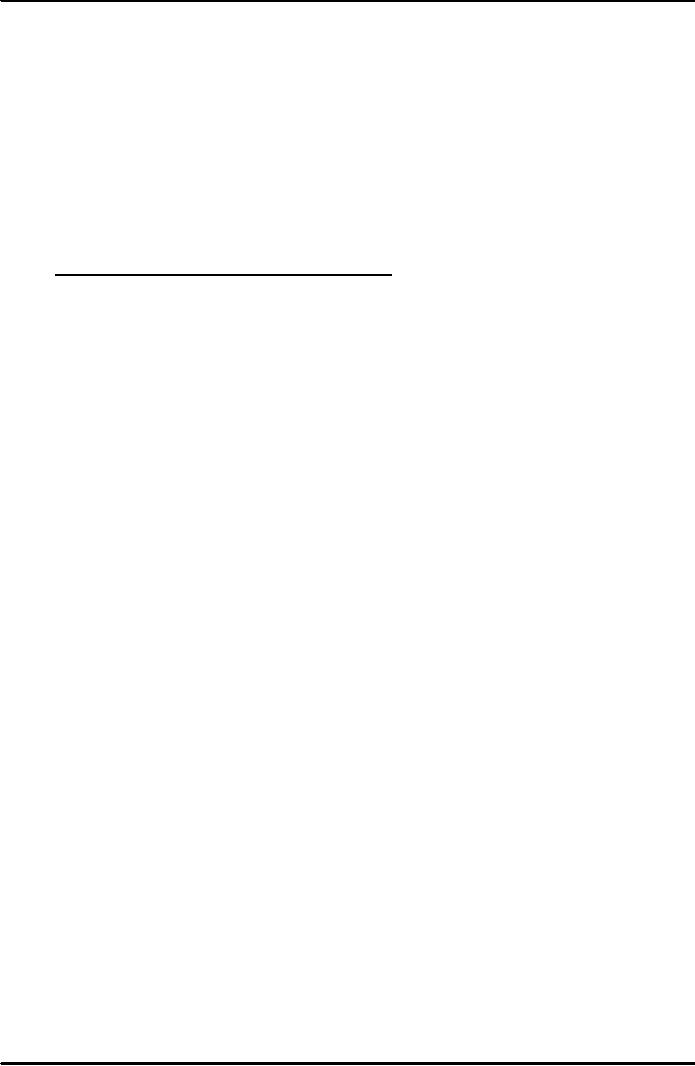

shown

in Figure 31.1 below, which

attempt to show interrelationships on bar charts. As

shown

in

the figure, task 1 and task 2

are related because of the

solid line between them. Task 3

and

task

4 can begin when task 2 is

half finished. (This cannot be shown

easily on PERT

without

splitting

activities.) The dotted

lines indicate slack. The

critical path can be

identified either by

putting

an asterisk (*) beside the critical

elements, by making the critical

connections in a

different-colored

ink, or by making the critical

path a boldface type.

221

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

Figure

31.1: Precedence

Network

The

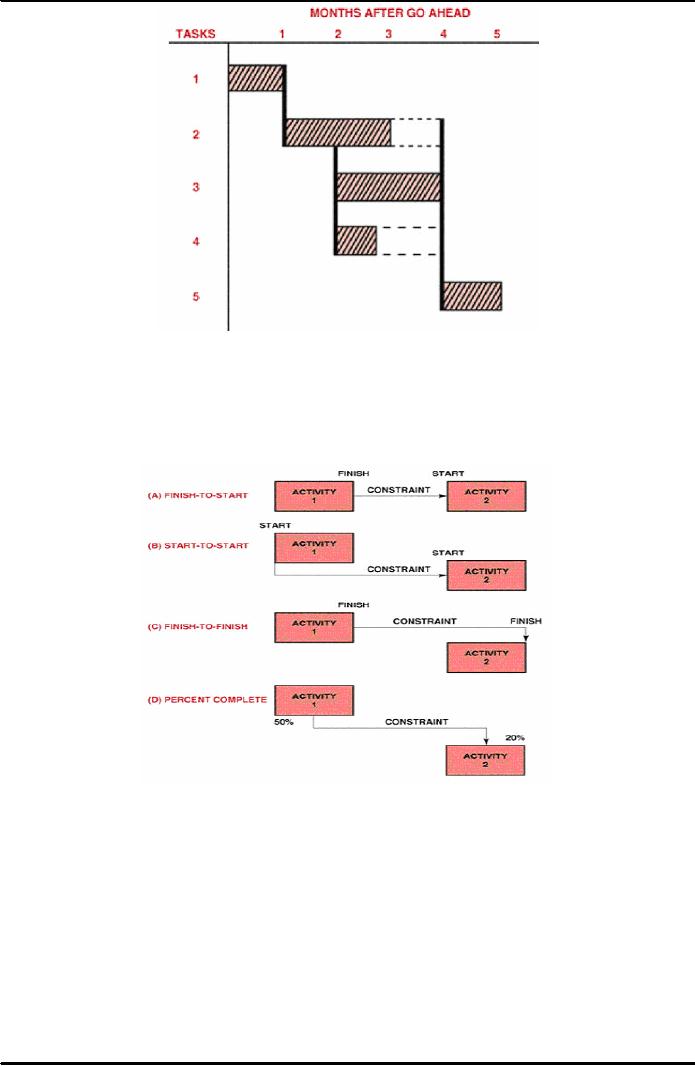

more sophisticated software packages

display precedence networks in the

format shown in

Figure

31.2 below. In each of these

figures, work is accomplished during the

activity. This is

sometimes

referred to as the activity-on-node method.

The arrow represents the

relationship or

constraint

between activities.

Figure

31.2: Typical

Precedence Relationships

Figure

above 31.2 (A) illustrates a

finish-to-start constraint. In this

figure, activity 2 can start

no

earlier

than the completion of activity 1.

Figure 31.2 (B) illustrates

a start-to-start constraint.

Activity

2 cannot start prior to the start of

activity 1. Figure 31.2 (C)

illustrates a finish-to-finish

constraint.

In this figure, activity 2 cannot

finish until activity 1

finishes. Lastly, Figure

31.2 (D)

illustrates

a percent-complete constraint. In this

figure, the last 20 percent of activity 2

cannot

be

started until 50 percent of activity 1

has been completed.

222

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

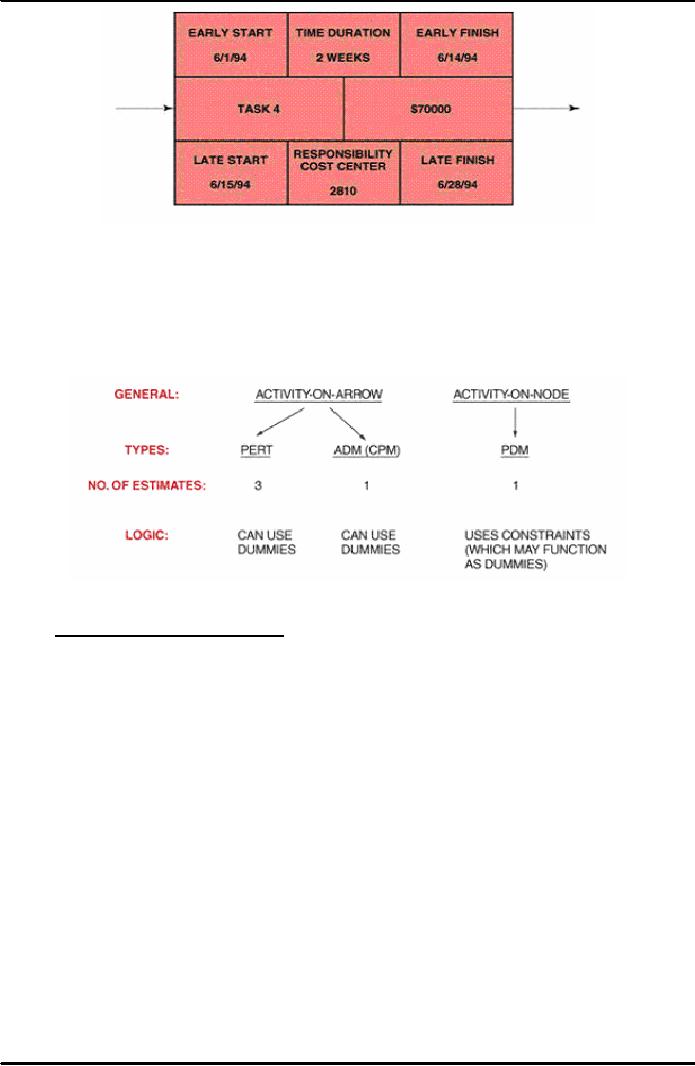

Figure

31.3: Computerized

Information Flow

Figure

31.3 above shows the typical

information that appears in

each of the activity

boxes

shown

in the previous figure. The

box identified as ''responsibility

cost center" could also

have

been

identified as the name, initials, or

badge number of the person responsible

for this activity.

Figure

31.4 below shows the comparison of three

of the different network

techniques.

Figure

31.4: Comparison of

Networks

31.2

PRICING

AND ESTIMATION:

As

we know that with the

complexities involved, it is not

surprising that many

business

managers

consider pricing an art. Having the

right intelligence information on

customer cost

budgets

and competitive pricing would

certainly help. However, the

reality is that

whatever

information

is available to one bidder is generally

available to the others. Even more

important,

intelligence

sources are often

unreliable. The only thing

worse than missing information,

is

wrong

or misleading information.

When

it comes to competitive pricing, the

old saying still applies:

"Those who talk don't

know;

and

those who know don't

talk!" It is true, partially,

that pricing remains an art.

However, a

disciplined

approach certainly helps one to develop

all the input for a rational

pricing

recommendation.

A side benefit of using a

disciplined management process is

that it leads to the

documentation

of the many factors and assumptions

involved at a later point in

time. These can

be

compared and analyzed, contributing to

the learning experiences that

make up the managerial

skills

needed for effective

business decisions.

Estimates

are not

blind

luck. They are

well-thought-out decisions based on the

best available

information,

some type of cost estimating

relationship, or some type of

cost model. Cost

estimating

relationships (CERs) are

generally the output of cost models.

Typical CERs might

be:

�

Mathematical

equations based on regression

analysis

�

Costquantity

relationships such as learning

curves

223

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

�

Costcost

relationships

�

Costnoncost

relationships based on physical

characteristics, technical parameters,

or

performance

characteristics

31.3

GLOBAL

PRICING STRATEGIES:

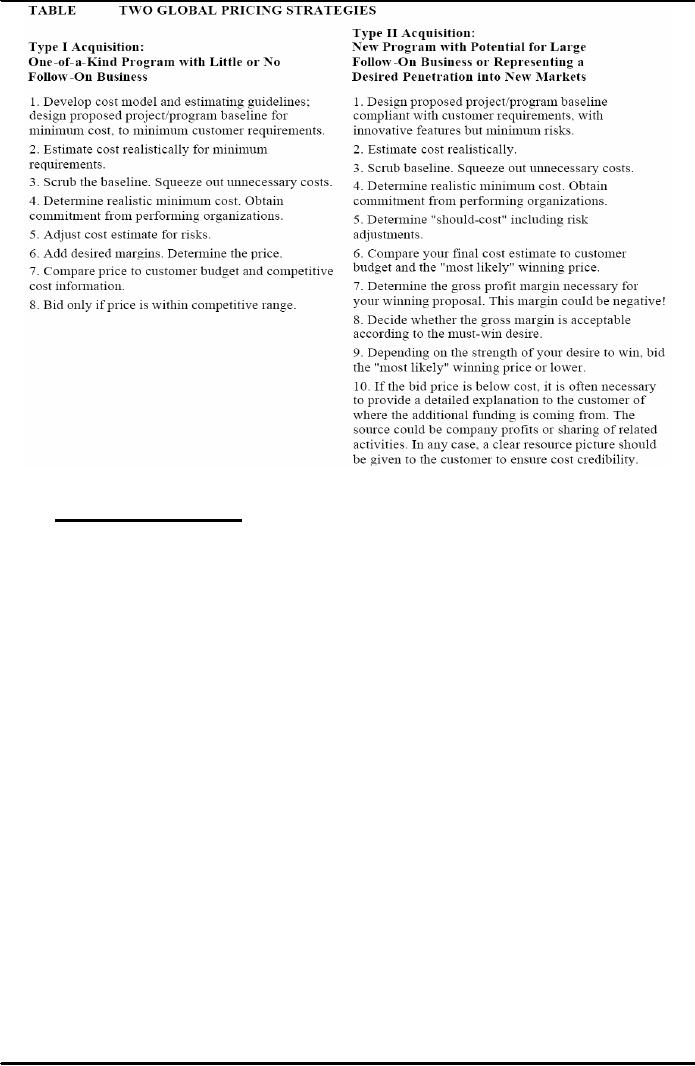

Specific

pricing strategies must be

developed for each

individual situation.

Frequently,

however,

one of two situations prevails

when one is pursuing project

acquisitions competitively.

First,

the new business opportunity

may be a one-of-a-kind program

with little or no

follow-on

potential;

a situation classified as type I

acquisition.

Second,

the new business opportunity

may be an entry point to a

larger follow-on or

repeat

business,

or may represent a planned

penetration into a new

market. This acquisition

is

classified

as type II.

Clearly,

in each case, we have specific

but different business

objectives. The objective

for type I

acquisition

is to win the program and execute it

profitably and satisfactorily

according to

contractual

agreements. The type II

objective is often to win the

program and perform

well,

thereby

gaining a foothold in a new

market segment or a new

customer community in place of

making

a profit.

Accordingly,

each acquisition type has

its own, unique pricing

strategy, as summarized in

Table

31.1

below.

Comparing

the two pricing strategies

for the two global

situations (as shown in Table

below)

reveals

a great deal of similarity for the

first five points. The

fundamental difference is that

for a

profitable

new business acquisition the

bid price is determined

according to actual cost,

whereas

in

a "must win" situation the

price is determined by the market

forces. It should be

emphasized

that

one of the most crucial inputs in the

pricing decision is the cost

estimate of the proposed

baseline.

The design of this baseline to the

minimum requirements should be started

early, in

accordance

with well defined ground

rules, cost models, and established cost

targets. Too often

the

baseline design is performed in parallel

with the proposal development. At the

proposal

stage

it is too late to review and

fine-tune the baseline for minimum

cost. Also, such a late

start

does

not allow much of an option

for a final bid decision.

Even if the price appears

outside the

competitive

range, it makes little sense to

terminate the proposal development. As

all the

resources

have been sent anyway, one

might just as well submit a

bid in spite of the remote

chance

of winning.

Clearly,

effective pricing begins a long

time before proposal

development. It starts

with

preliminary

customer requirements, well-understood

subtasks, and a top-down estimate

with

should-cost

targets.

This

allows the functional organization to

design a baseline to meet the customer

requirements

and

cost targets, and gives

management the time to review and

redirect the design before the

proposal

is submitted. Furthermore, it gives

management an early opportunity to

assess the

chances

of winning during the acquisition

cycle, at a point in time

when additional

resources

can

be allocated or the acquisition effort

can be terminated before too

many resources are

committed

to a hopeless effort.

The

final pricing review session

should be an integration and review of

information already

well

known

in its basic context. The

process and management tools

outlined here should help

to

provide

the framework and discipline for

deriving pricing decisions in an orderly

and effective

way.

224

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

Table

31.1: Two

Global Pricing

Strategies

31.4

TYPES

OF ESTIMATES:

Note

that projects can range from a

feasibility study, through

modification of existing

facilities,

to

complete design, procurement, and construction of a

large complex. Whatever the

project

may

be, whether large or small,

the estimate and type of information

desired may differ

radically.

The

first type of estimate is an

order-of-magnitude

analysis,

which is made without any

detailed

engineering

data. The order-of-magnitude analysis may

have an accuracy of �35 percent

within

the

scope of the project. This

type of estimate may use

past experience (not necessarily

similar),

scale

factors, parametric curves or capacity

estimates (that is, $/# of

product or $/KW

electricity).

Next,

there is the approximate

estimate (or

top-down estimate), which is also

made without

detailed

engineering data, and may be accurate to

�15 percent. This type of

estimate is prorated

from

previous projects that are

similar in scope and

capacity, and may be titled

as estimating by

analogy,

parametric curves, rule of thumb,

and indexed cost of similar

activities adjusted for

capacity

and technology. In such a case, the

estimator may say that this

activity is 50 percent

more

difficult than a previous

(i.e., reference) activity and requires

50 percent more time, man-

hours,

dollars, materials, and so on.

The

definitive

estimate, or

grassroots buildup estimate, is prepared

from well-defined

engineering

data including (as a

minimum) vendor quotes,

fairly complete plans,

specifications,

unit

prices, and estimate to complete. The

definitive estimate, also

referred to as detailed

estimating,

has an accuracy of �5 percent.

Another

method for estimating is the use of

learning

curves. Learning

curves are graphical

representations

of repetitive functions in which

continuous operations will lead to a

reduction in

225

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

time,

resources, and money. The

theory behind learning

curves is usually applied

to

manufacturing

operations.

Each

company may have a unique approach to

estimating. However, for

normal project

management

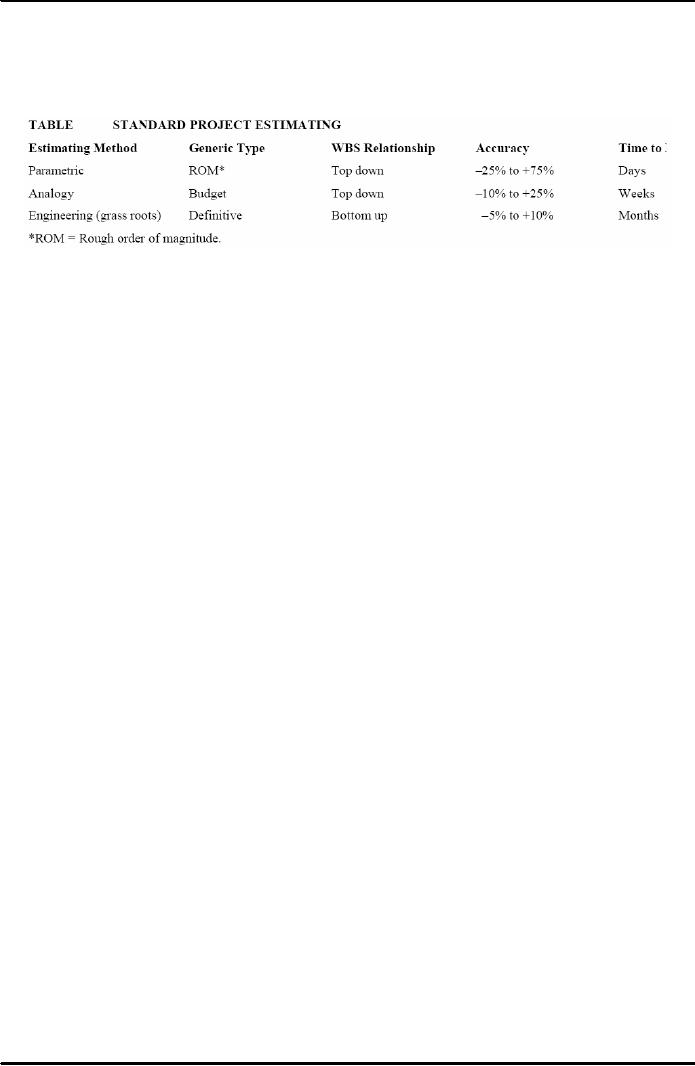

practices, Table 31.2 below

would suffice as a starting

point.

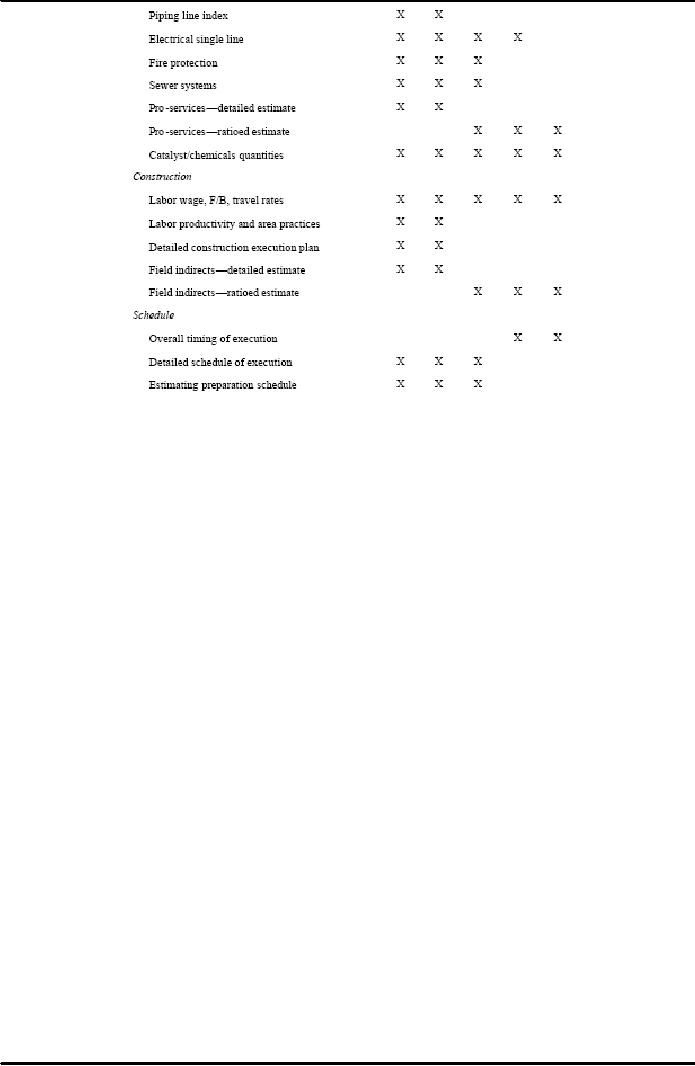

Table

31.2: Standard

Project Estimating

Many

companies try to standardize their

estimating procedures by developing an

estimating

manual.

The

estimating manual is then

used to price out the

effort, perhaps as much as

90

percent.

Estimating manuals usually

give better estimates than

industrial engineering

standards

because

they include groups of tasks and

take into consideration such

items as downtime,

cleanup

time, lunch, and breaks.

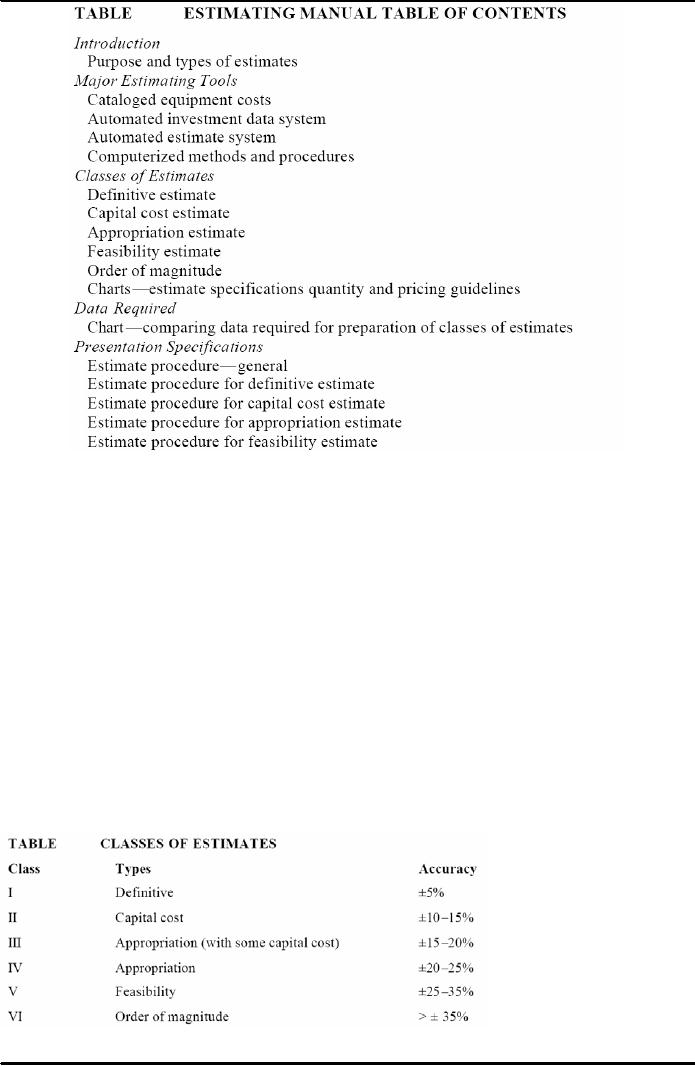

Table 31.3 below shows the

table of contents for a

construction

estimating

manual.

Estimating

manuals, as the name implies,

provide estimates. The

question, of course, is

"How

good

are the estimates?" Most

estimating manuals provide

accuracy limitations by defining

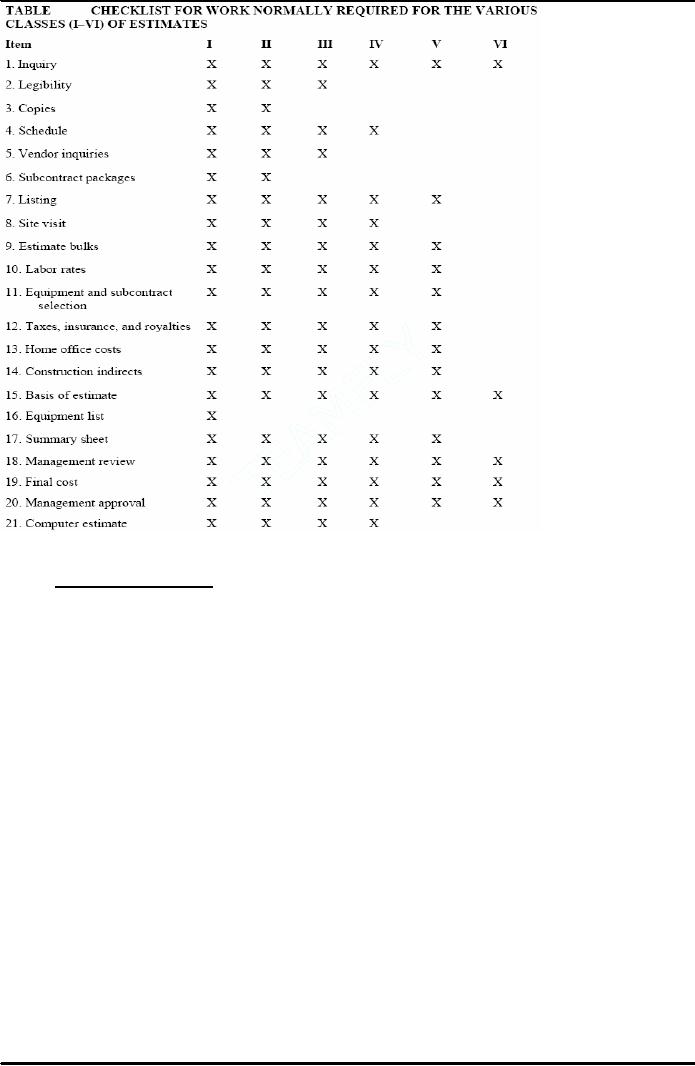

the

type

of estimates (shown in Table

31.4 below). Using Table

below, we can create the

next three

tables

which illustrate the use of the

estimating manual.

Not

all companies can use

estimating manuals. Estimating

manuals work best for

repetitive

tasks

or similar tasks that can

use a previous estimate adjusted by a

degree-of-difficulty factor.

Activities

such as Research and

Development do not lend

themselves to the use of

estimating

manuals

other than for benchmark,

repetitive laboratory

tests.

Proposal

managers must carefully consider

whether the estimating manual is a

viable approach.

The

literature abounds with

examples of companies that have

spent millions trying to

develop

estimating

manuals for situations that

just do not lend themselves

to the approach.

226

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

Table

31.3: Estimating

Manual Table of Contents

During

competitive bidding, it is important

that the type of estimate be

consistent with the

customer's

requirements. For in-house projects, the

type of estimate can vary

over the life cycle

of

a project:

�

Conceptual

Stage:

Venture

guidance or feasibility studies for the

evaluation of future work.

This estimating is

often

based on minimum-scope

information.

�

Planning

Stage:

Estimating

for authorization of partial or

full funds. These estimates

are based on

preliminary

design and scope.

�

Main

Stage:

Estimating

for detailed work.

�

Termination

Stage:

Re-estimation

for major scope changes or

variances beyond the authorization

range.

Table

31.4: Classes

of Estimates

227

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

Table

31.5: Checklist

for Work Normally Required

for the Various Classes of

Estimates

31.5

PRICING

PROCESS:

This

activity schedules the development of the

Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) and

provides

management

with two of the three operational

tools necessary for the

control of a system or

project.

The development of these two

tools is normally the responsibility of

the program office

with

input from the functional

units.

Note

that the integration of the functional

unit into the project

environment or system

occurs

through

the pricing-out of the work breakdown

structure. The total program

costs obtained by

pricing

out the activities over the

scheduled period of performance provide

management with

the

third tool necessary to successfully

manage the project. During the

pricing activities, the

functional

units have the option of consulting

program management about possible

changes in

the

activity schedules and work

breakdown structure.

228

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

229

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

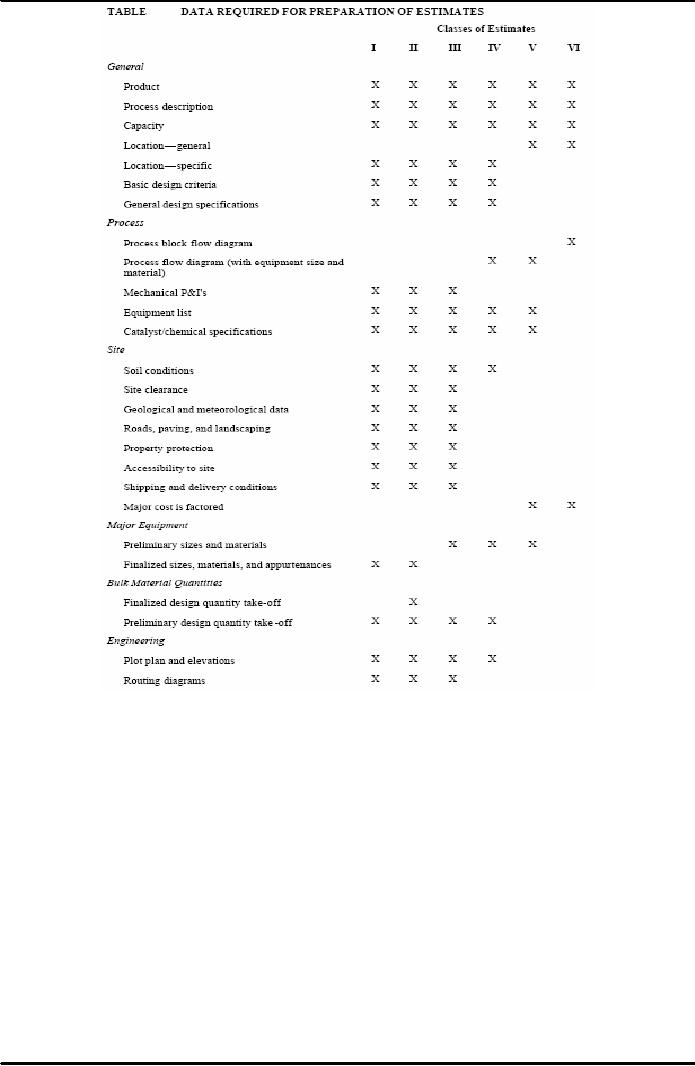

Table

31.6: Data

Required for Preparation of

Estimates

The

Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) and

activity schedules are

priced out through the

lowest

pricing

units of the company. It is the

responsibility of these pricing

units, whether they

are

sections,

departments, or divisions, to provide

accurate and meaningful cost

data (based on

historical

standards, if possible). All information is

priced out at the lowest

level of performance

required,

which, will be the task

level. Costing information is

rolled up to the project level

and

then

one step further to the total

program level.

Under

ideal conditions, the work

required (that is, man-hours) to complete a

given task can be

based

on historical standards. Unfortunately,

for many industries, projects

and programs are so

diversified

that realistic comparison between

previous activities may not

be possible. The

costing

information obtained from

each pricing unit, whether

or not it is based on

historical

standards,

should be regarded only as an estimate.

How can a company predict the

salary

structure

three years from now? What

will be the cost of raw materials

two years from

now?

Will

the business base (and

therefore overhead rates) change

over the duration of the program?

The

final response to these questions

shows that costing data

are explicitly related to

an

environment

that cannot be predicted with

any high degree of

certainty. The systems

approach

to

management, however, provides

for a more rapid response to the

environment than less

structured

approaches permit.

Remember

that once the cost data

are assembled, they must be

analyzed for their

potential

impact

on the company resources of people,

money, equipment, and facilities. It is

only through

a

total program cost analysis

that resource allocations

can be analyzed. The resource

allocation

analysis

is performed at all levels of

management, ranging from the section

supervisor to the

vice

president and general manager. For most programs, the

chief executive must approve

final

cost

data and the allocation of

resources.

Proper

analysis of the total program costs

can provide management (both

program and

corporate)

with a strategic planning model

for integration of the current

program with other

programs

in order to obtain a total corporate

strategy. Meaningful planning and

pricing models

include

analyses for monthly

man-loading schedules per department,

monthly costs per

department,

monthly and yearly total

program costs, monthly

material expenditures, and

total

program

cash-flow and man-hour requirements per

month.

230

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

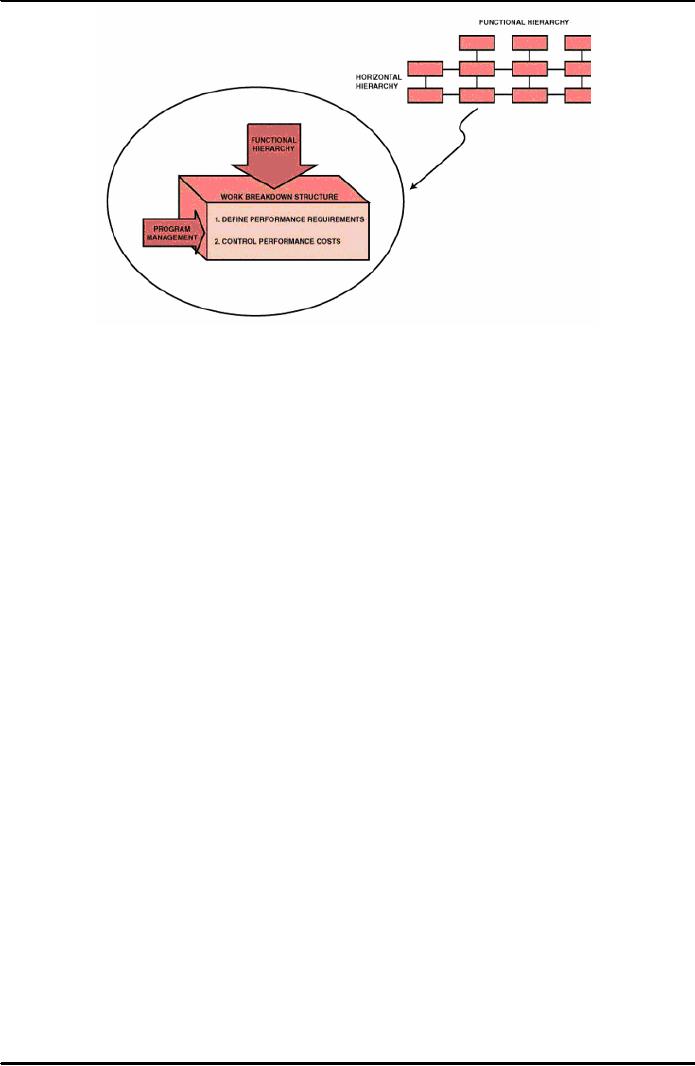

Figure

31.5: The

Vertical Horizontal

Interface

Previously

we identified several of the problems that occur at

the nodes where the horizontal

hierarchy

of program management interfaces with the

vertical hierarchy of

functional

management.

The

pricing-out of the work breakdown

structure provides the basis for

effective and open

communication

between functional and program

management where both parties have one

common

goal.

This is shown in Figure 31.5 above.

After the pricing effort is

completed, and the program is

initiated,

the work breakdown structure still

forms the basis of a communications tool

by documenting

the

performance agreed on in the pricing

effort, as well as establishing the

criteria against which

performance

costs will be

measured.

231

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Broad Contents, Functions of Management

- CONCEPTS, DEFINITIONS AND NATURE OF PROJECTS:Why Projects are initiated?, Project Participants

- CONCEPTS OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT:THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT SYSTEM, Managerial Skills

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT METHODOLOGIES AND ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES:Systems, Programs, and Projects

- PROJECT LIFE CYCLES:Conceptual Phase, Implementation Phase, Engineering Project

- THE PROJECT MANAGER:Team Building Skills, Conflict Resolution Skills, Organizing

- THE PROJECT MANAGER (CONTD.):Project Champions, Project Authority Breakdown

- PROJECT CONCEPTION AND PROJECT FEASIBILITY:Feasibility Analysis

- PROJECT FEASIBILITY (CONTD.):Scope of Feasibility Analysis, Project Impacts

- PROJECT FEASIBILITY (CONTD.):Operations and Production, Sales and Marketing

- PROJECT SELECTION:Modeling, The Operating Necessity, The Competitive Necessity

- PROJECT SELECTION (CONTD.):Payback Period, Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

- PROJECT PROPOSAL:Preparation for Future Proposal, Proposal Effort

- PROJECT PROPOSAL (CONTD.):Background on the Opportunity, Costs, Resources Required

- PROJECT PLANNING:Planning of Execution, Operations, Installation and Use

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Outside Clients, Quality Control Planning

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Elements of a Project Plan, Potential Problems

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Sorting Out Project, Project Mission, Categories of Planning

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Identifying Strategic Project Variables, Competitive Resources

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Responsibilities of Key Players, Line manager will define

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):The Statement of Work (Sow)

- WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE:Characteristics of Work Package

- WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE:Why Do Plans Fail?

- SCHEDULES AND CHARTS:Master Production Scheduling, Program Plan

- TOTAL PROJECT PLANNING:Management Control, Project Fast-Tracking

- PROJECT SCOPE MANAGEMENT:Why is Scope Important?, Scope Management Plan

- PROJECT SCOPE MANAGEMENT:Project Scope Definition, Scope Change Control

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Historical Evolution of Networks, Dummy Activities

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Slack Time Calculation, Network Re-planning

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Total PERT/CPM Planning, PERT/CPM Problem Areas

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION:GLOBAL PRICING STRATEGIES, TYPES OF ESTIMATES

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.):LABOR DISTRIBUTIONS, OVERHEAD RATES

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.):MATERIALS/SUPPORT COSTS, PRICING OUT THE WORK

- QUALITY IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Value-Based Perspective, Customer-Driven Quality

- QUALITY IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT (CONTD.):Total Quality Management

- PRINCIPLES OF TOTAL QUALITY:EMPOWERMENT, COST OF QUALITY

- CUSTOMER FOCUSED PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Threshold Attributes

- QUALITY IMPROVEMENT TOOLS:Data Tables, Identify the problem, Random method

- PROJECT EFFECTIVENESS THROUGH ENHANCED PRODUCTIVITY:Messages of Productivity, Productivity Improvement

- COST MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL IN PROJECTS:Project benefits, Understanding Control

- COST MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL IN PROJECTS:Variance, Depreciation

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT THROUGH LEADERSHIP:The Tasks of Leadership, The Job of a Leader

- COMMUNICATION IN THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Cost of Correspondence, CHANNEL

- PROJECT RISK MANAGEMENT:Components of Risk, Categories of Risk, Risk Planning

- PROJECT PROCUREMENT, CONTRACT MANAGEMENT, AND ETHICS IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Procurement Cycles