|

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

LESSON

25

TOTAL

PROJECT PLANNING

BROAD

CONTENTS

Total

Project Planning

Project

Charter

Management

Control

Project

ManagerLine Manager

Interface

Project

Fast Tracking

Configuration

Management

25.1

Total

Project Planning:

Planning

is one of the most significant

functions of management. The

difference between good

project

manager and poor project

manager is often described in one word:

planning.

Unfortunately,

people have a poor definition of

what project planning

actually involves.

Project

planning

involves planning

for:

�

Schedule

development

�

Budget

development

�

Project

administration

�

Leadership

styles (interpersonal influences)

�

Conflict

management

With

reference to this, the first two items

involve the quantitative aspects of

planning. Planning

for

project

administration includes the development

of the Linear Responsibility Chart

(LRC).

We

know that although each

project manager has the

authority and responsibility to

establish

project

policies and procedures, they

must fall within the general

guidelines established by top

management.

Guidelines can also be established

for planning, scheduling,

controlling, and

communications.

Note

that the Linear Responsibility

Chart (LRC) can result

from customer-imposed requirements

above

and beyond normal operations. For

example, the customer may

require as part of his

quality

control

requirements that a specific engineer

supervise and approve all

testing of a certain item,

or

that

another individual approve all

data released to the customer

over and above program

office

approval.

Customer requirements similar to those

identified above require

Linear Responsibility

Charts

(LRCs) and can cause

disruptions and conflicts within an

organization.

There

are several key factors that

affect the delegation of authority and

responsibility both

from

upper-level

management to project management, and

from project management to

functional

management.

These key factors

include:

�

Maturity

of the project management

function

�

Size,

nature, and business base of the

company

�

Size

and nature of the project

�

Life

cycle of the project

�

Capabilities

of management at all

levels

Once

agreement has been reached

on the project manager's authority and

responsibility, the

results

may be documented to delineate that

role regarding:

172

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

�

Focal

position

�

Conflict

between the project manager and

functional managers

�

Influence

to cut across functional and

organizational lines

�

Participation

in major management and technical

decisions

�

Collaboration

in staffing the project

�

Control

over allocation and expenditure of

funds

�

Selection

of subcontractors

�

Rights

in resolving conflicts

�

Input

in maintaining the integrity of the

project team

�

Establishment

of project plans

�

Provisions

for a cost-effective information

system for control

�

Provisions

for leadership in preparing operational

requirements

�

Maintenance

of prime customer liaison and

contact

�

Promotion

of technological and managerial

improvements

�

Establishment

of project organization for the

duration

�

Elimination

of red tape

In

addition to this, documenting the

project manager's authority is

necessary in some

situations

because:

�

All

interfacing must be kept as

simple as possible.

�

Project

manager must have the authority to

"force" functional managers to depart

from

existing

standards and possibly incur

risk.

�

Gaining

authority over those

elements of a program that

are not under the project

manager's

control

is essential. This is normally achieved

by earning the respect of the

individuals

concerned.

�

The

project manager should not

attempt to fully describe the exact

authority and

responsibilities

of the project office personnel or team

members. Problem solving

rather

than

role definition should be

encouraged.

In

most cases, although

documenting project authority is

undesirable, it may be a

necessary

prerequisite,

especially if project initiation and

planning require a formal

project chart. Power and

authority

are often discussed as

though they go hand in hand. Authority

comes from people

above

you,

perhaps by delegation, whereas

power comes from people

below you. You can have

authority

without

power or power without

authority.

Most

individuals maintain position

power in a traditional organizational

structure. The higher up

you

sit, the more power you have.

But in project management, the

reporting level of the

project

might

be irrelevant, especially if a project

sponsor exists. In project management,

the project

manager's

power base emanates from

his:

�

Expertise

(technical or managerial)

�

Credibility

with employees

�

Sound

decision-making ability

Keeping

in view its significance, the last

item is usually preferred. If the

project manager is

regarded

as a sound decision maker,

then the employees normally give the

project manager a great

deal

or power over them.

Here

it is important to discuss leadership.

Leadership styles refer to the

interpersonal influence

modes

that a project manager can

use. Project managers may

have to use several different

leadership

styles, depending on the makeup of the project

personnel. Conflict management is

173

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

important

because if the project manager

can predict what conflicts

will occur and when they

are

most

likely to occur, he may be

able to plan for the

resolution of the conflicts through

project

administration.

The object, of course, is to

develop a project plan that

shows complete distribution

of

resources and the corresponding costs.

The project manager begins

with a coarse (arrow

diagram)

network

and then decides on the Work

Breakdown Structure (WBS). The

Work Breakdown

Structure

(WBS) is essential to the arrow

diagram and should be constructed so

that reporting

elements

and levels are easily

identifiable.

For

each element in the Work Breakdown

Structure (WBS), eventually there will be

an arrow

diagram

and detailed chart. If there exists too

much detail, the project

manager can refine

the

diagram

by combining all logic into

one plan and can then decide on the

work assignments. There

is

a

risk here that, by condensing the

diagrams as much as possible, there may be a

loss of clarity. All

the

charts and schedules can be

integrated into one

summary-level figure. This

can be

accomplished

at each Work Breakdown Structure

(WBS) level until the desired

plan is achieved.

Moving

ahead, finally, project,

line, and executive management

must analyze other internal

and

external

variables before finalizing

these schedules. A partial

listing of these variables

includes:

�

Introduction

or acceptance of the product in the

marketplace

�

Present

or planned manpower availability

�

Economic

constraints of the project

�

Degree

of technical difficulty

�

Manpower

availability

�

Availability

of personnel training

�

Priority

of the project

In

small companies and projects, certain

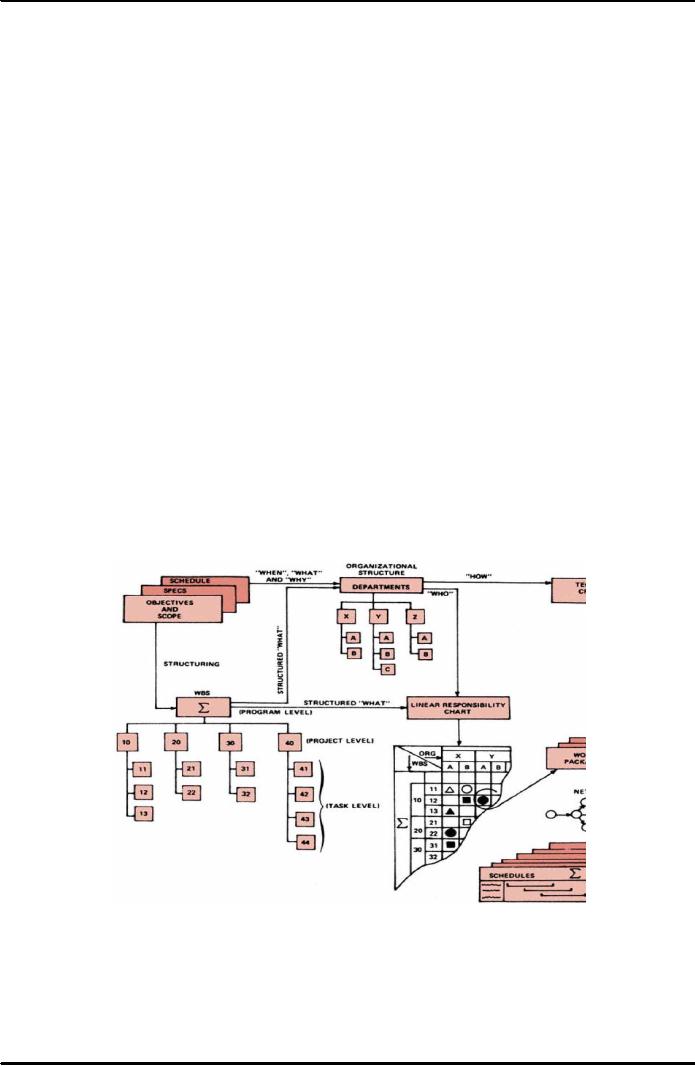

items in the figure 25.1 below

may be omitted, such as

the

Linear

Responsibility Chart

(LRC).

Figure

25.1: Project

Planning

25.2

The

Project Charter:

Initially,

the original concept behind the

project charter was to document the

project manager's

authority

and responsibility, especially for

projects implemented away from the

home office.

Today,

the project charter has been expanded to

become more of an internal legal

document

174

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

identifying

to the line managers and his personnel

not only the project

manager's authority

and

responsibility,

but also the management-

and/or customer-approved scope of the

project.

In

theoretical terms, the sponsor

prepares the charter and affixes his/her

signature, but in reality,

the

project manager may prepare it

for the sponsor's signature. At a

minimum, the charter

should

include:

�

Identification

of the project manager and his/her

authority to apply resources to the

project

�

The

business purpose that the

project was undertaken to

address, including all

assumptions

and

constraints

�

Summary

of the conditions defining the

project

What

is a "charter"? It is a "legal" agreement

between the project manager and the

company. Some

companies

supplement the charter with a "contract"

that functions as an agreement between

the

project

and the line organizations.

Recently,

within the last two years or

so, some companies have

converted the charter into a

highly

detailed

document containing:

�

The

scope baseline/scope

statement

�

Scope

and objectives of the project (Statement of

Work (SOW)

�

Specifications

�

Work

Breakdown Structure (template

levels)

�

Timing

�

Spending

plan (S-curve)

�

Management

plan

�

Resource

requirements and man loading (if

known)

�

R�sum�s

of key personnel

�

Organizational

relationships and structure

�

Responsibility

assignment matrix

�

Support

required from other

organizations

�

Project

policies and procedures

�

Change

management plan

�

Management

approval of above

The

project charter may function as the

project plan when it contains a

scope baseline and

management

plan. This is not really an

effective use of the charter,

but it may be acceptable

on

certain

types of projects for internal

customers.

25.3

Management

Control:

It

is essential that careful

management control must be established

because the planning

phase

provides

the fundamental guidelines for the

remainder of the project. In addition,

since planning is

an

ongoing activity for a

variety of different programs,

management guidelines must be

established

on

a company-wide basis in order to achieve

unity and coherence.

Note

that all functional

organizations and individuals working

directly or indirectly on a

program

are

responsible for identifying, to the

project manager, scheduling and

planning problems that

require

corrective action during

both the planning cycle and the

operating cycle. The

program

manager

bears the ultimate and final

responsibility for identifying

requirements for corrective

actions.

175

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

For

this purpose, management policies and

directives are written

specifically to assist

the

program

manager in defining the requirements.

Without clear definitions during the

planning

phase,

many projects run off in a

variety of directions.

In

this regard, many companies establish

planning and scheduling

management policies for

the

project

and functional managers, as

well as a brief description of

how they should

interface.

25.4

The

Project ManagerLine Manager

Interface:

Good

project planning, as well as

other project functions, requires a

good working

relationship

between

the project and line managers.

The utilization of management

controls does not

necessarily

guarantee successful project

planning. At this

interface:

�

The

project manager answers the

following questions:

What

is to be done? (Using the Statement of

Work, Work Breakdown

Structure)

o

When

will the task be done?

(Using the summary schedule)

o

Why

will the task be done?

(Using the Statement of

Work)

o

How

much money is available?

(Using the Statement of

Work)

o

�

The

line manager answers the

following questions:

How

will the task be done?

(i.e., technical

criteria)

o

Where

will the task be done?

(i.e., technical

criteria)

o

Who

will do the task? (i.e.,

staffing)

o

Furthermore,

project managers may be able

to tell line managers ''how"

and "where," provided

that

the information appears in the Statement

of Work (SOW) as a requirement

for the project.

Even

then, the line manager can

take exception based on his

technical expertise.

The

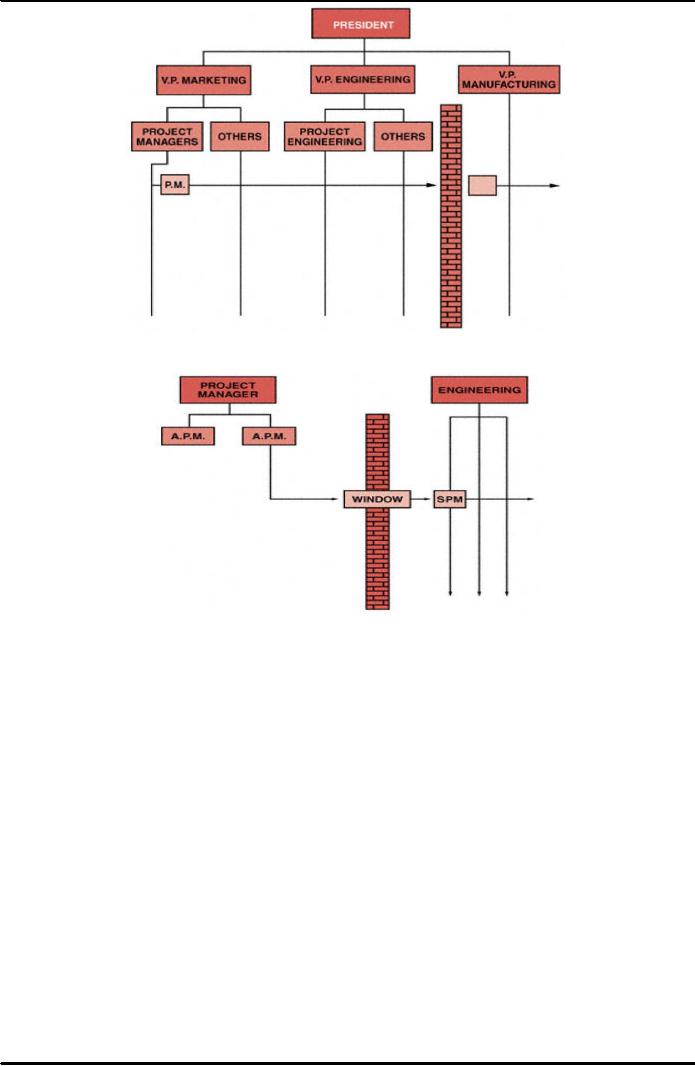

following figures 25.2 and

25.3, that is, "The Brick

Wall" and "Modified Brick

Wall"

respectively,

show what can happen when

project managers overstep their bounds.

In Figure

25.2

below, the manufacturing manager

built a brick wall to keep the

project managers away

from

his personnel because the project

managers were telling his

line people how to do

their

job.

In Figure 25.3 "Modified

Brick Wall", the subproject managers

(for simplicity's

sake,

equivalent

to project engineers) would have, as

their career path,

promotions to Assistant

Project

Managers (A.P.Ms). Unfortunately, the

Assistant Project Managers still

felt that they

were

technically competent enough to give

technical direction, and this

created havoc for the

engineering

managers.

In

view of this, the simplest solution to

all of these problems is for the

project manager to

provide

the technical direction through

the

line managers. After all,

the line managers are

supposedly

the true technical experts.

176

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

Figure

25.2: The

Brick Wall

Figure

25.3: Modified

Brick Wall

25.5

Project

Fast-Tracking:

No

matter how well we plan,

sometimes something happens that

causes havoc on the project.

Such

is the case when either the

customer or management changes the

project's constraints.

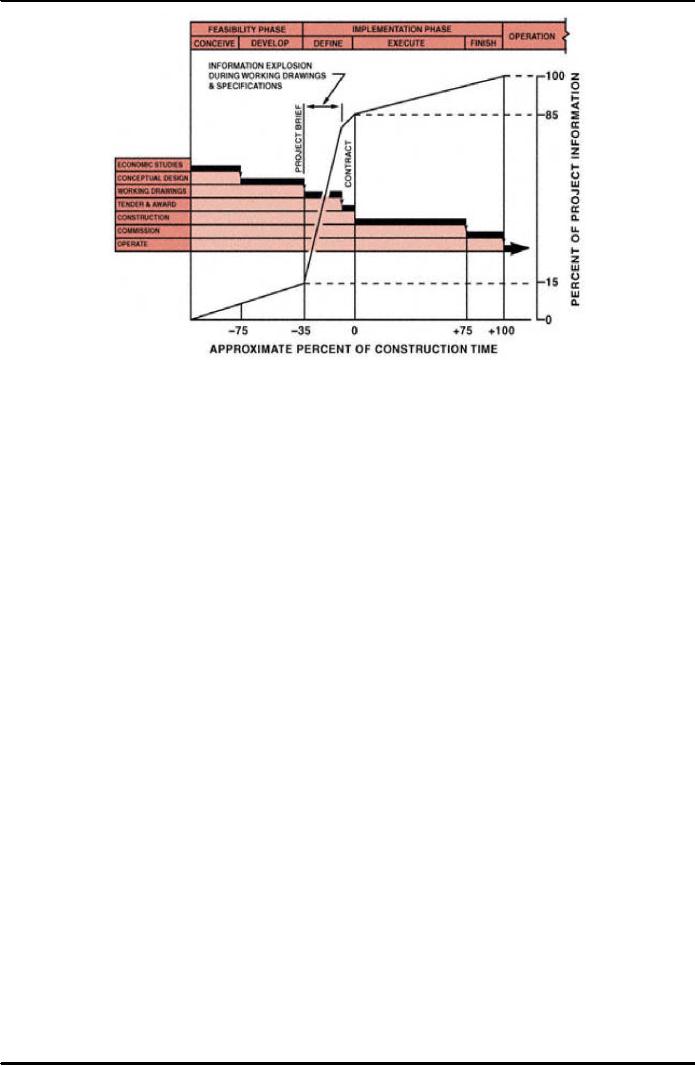

Consider

Figure 25.4 "The information

explosion" and let us assume

that the execution time

for

the

construction of the project is one year.

To prepare the working drawings and

specifications

down

through level 5 of the Work

Breakdown Structure (WBS) would

require an additional 35

percent

of the expected execution time, and if a

feasibility study is required, then an

additional

40

percent will be added on. In

other words, if the execution phase of

the project is one

year,

then

the entire project is almost two

years.

Let

us now assume that

management wishes to keep the end date

fixed but the start date

is

delayed

because of lack of adequate

funding. How can this be

accomplished without

sacrificing

the

quality?

What

should be the answer to it?

The answer is to fast-track the

project. Fast-tracking a

project

means

that activities that are

normally done in series are done in

parallel. An example of this

is

when

construction begins before detail design

is completed.

177

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

Figure

25.4: The

Information Explosion

Now

the question arises as to how

would this help.

Fast-tracking a job can

accelerate the

schedule

but requires that additional risks be

taken. If the risks materialize, then

either the end

date

will slip or expensive

rework will be needed.

Almost all project driven

companies fast-

track

projects. The danger, however, is

when fast-tracking becomes a

way of life on all

projects.

25.6

Configuration

Management:

Configuration

management or configuration change

control is one of the most critical

tools

employed

by a project manager. As projects progress downstream

through the various

life-cycle

phases,

the cost of engineering changes

can grow boundlessly. It is

not uncommon for

companies

to bid on proposals at 40 percent below

their own cost hoping to

make up the

difference

downstream with engineering changes. It

is also quite common for executives

to

"encourage"

project managers to seek out

engineering changes because of

their profitability.

What

is configuration management? It is a

control technique, through an

orderly process, for

formal

review and approval of configuration

changes. If properly implemented,

configuration

management

provides:

�

Appropriate

levels of review and approval

for changes

�

Focal

points for those seeking to

make changes

�

A

single point of input to

contracting representatives in the customer's and

contractor's

office

for approved changes

At

a minimum, the configuration control

committee should include representation

from the

customer,

contractor, and line group

initiating the change. Discussions

should answer the

following

questions:

�

What

is the cost of the change?

�

Do

the changes improve

quality?

�

Is

the additional cost for this

quality justifiable?

�

Is

the change necessary?

�

Is

there an impact on the delivery

date?

178

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

As

we know that changes cost

money. Therefore, it is imperative

that configuration management

be

implemented

correctly. The following

steps can enhance the

implementation process:

�

Define

the starting point or "baseline"

configuration

�

Define

the "classes" of changes

�

Define

the necessary controls or limitations on

both the customer and contractor

�

Identify

policies and procedures,

such as:

o

Board

chairman

o

Voters/alternatives

o

Meeting

time

o

Agenda

o

Approval

forums

o

Step-by-step

processes

o

Expedition

processes in case of

emergencies

It

is essential to know that

effective configuration control

pleases both customer and

contractor.

Overall

benefits include:

�

Better

communication among staff

�

Better

communication with the

customer

�

Better

technical intelligence

�

Reduced

confusion for changes

�

Screening

of frivolous changes

�

Providing

a paper trail

Lastly,

but importantly, it must be understood

that configuration control, as

used here, is not a

replacement

for design review meetings or customer

interface meetings. These meetings are

still

an

integral part of all

projects.

179

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Broad Contents, Functions of Management

- CONCEPTS, DEFINITIONS AND NATURE OF PROJECTS:Why Projects are initiated?, Project Participants

- CONCEPTS OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT:THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT SYSTEM, Managerial Skills

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT METHODOLOGIES AND ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES:Systems, Programs, and Projects

- PROJECT LIFE CYCLES:Conceptual Phase, Implementation Phase, Engineering Project

- THE PROJECT MANAGER:Team Building Skills, Conflict Resolution Skills, Organizing

- THE PROJECT MANAGER (CONTD.):Project Champions, Project Authority Breakdown

- PROJECT CONCEPTION AND PROJECT FEASIBILITY:Feasibility Analysis

- PROJECT FEASIBILITY (CONTD.):Scope of Feasibility Analysis, Project Impacts

- PROJECT FEASIBILITY (CONTD.):Operations and Production, Sales and Marketing

- PROJECT SELECTION:Modeling, The Operating Necessity, The Competitive Necessity

- PROJECT SELECTION (CONTD.):Payback Period, Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

- PROJECT PROPOSAL:Preparation for Future Proposal, Proposal Effort

- PROJECT PROPOSAL (CONTD.):Background on the Opportunity, Costs, Resources Required

- PROJECT PLANNING:Planning of Execution, Operations, Installation and Use

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Outside Clients, Quality Control Planning

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Elements of a Project Plan, Potential Problems

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Sorting Out Project, Project Mission, Categories of Planning

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Identifying Strategic Project Variables, Competitive Resources

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Responsibilities of Key Players, Line manager will define

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):The Statement of Work (Sow)

- WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE:Characteristics of Work Package

- WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE:Why Do Plans Fail?

- SCHEDULES AND CHARTS:Master Production Scheduling, Program Plan

- TOTAL PROJECT PLANNING:Management Control, Project Fast-Tracking

- PROJECT SCOPE MANAGEMENT:Why is Scope Important?, Scope Management Plan

- PROJECT SCOPE MANAGEMENT:Project Scope Definition, Scope Change Control

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Historical Evolution of Networks, Dummy Activities

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Slack Time Calculation, Network Re-planning

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Total PERT/CPM Planning, PERT/CPM Problem Areas

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION:GLOBAL PRICING STRATEGIES, TYPES OF ESTIMATES

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.):LABOR DISTRIBUTIONS, OVERHEAD RATES

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.):MATERIALS/SUPPORT COSTS, PRICING OUT THE WORK

- QUALITY IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Value-Based Perspective, Customer-Driven Quality

- QUALITY IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT (CONTD.):Total Quality Management

- PRINCIPLES OF TOTAL QUALITY:EMPOWERMENT, COST OF QUALITY

- CUSTOMER FOCUSED PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Threshold Attributes

- QUALITY IMPROVEMENT TOOLS:Data Tables, Identify the problem, Random method

- PROJECT EFFECTIVENESS THROUGH ENHANCED PRODUCTIVITY:Messages of Productivity, Productivity Improvement

- COST MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL IN PROJECTS:Project benefits, Understanding Control

- COST MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL IN PROJECTS:Variance, Depreciation

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT THROUGH LEADERSHIP:The Tasks of Leadership, The Job of a Leader

- COMMUNICATION IN THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Cost of Correspondence, CHANNEL

- PROJECT RISK MANAGEMENT:Components of Risk, Categories of Risk, Risk Planning

- PROJECT PROCUREMENT, CONTRACT MANAGEMENT, AND ETHICS IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Procurement Cycles