|

SCHEDULES AND CHARTS:Master Production Scheduling, Program Plan |

| << WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE:Why Do Plans Fail? |

| TOTAL PROJECT PLANNING:Management Control, Project Fast-Tracking >> |

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

LESSON

24

SCHEDULES

AND CHARTS

BROAD

CONTENTS

Detailed

Schedules and Charts

Guidelines

for Preparation of

Schedules

Preparation

Sequence of Schedules

Master

Production Scheduling

Definition

of Master Production Schedule

(MPS)

Objectives

of Master Production Schedule

(MPS)

Program

Plan

24.1

Detailed

Schedules and

Charts:

The

first major requirement of the

program office after the

program goes ahead is

the

scheduling

of activities.

If

the activity is not too

complex, the program office

normally assumes full

responsibility for

activity

scheduling. For large programs,

functional management input is

required before

scheduling

can be completed.

Depending

on program size and contractual

requirements, it is not unusual for the

program

office

to maintain, at all times, a program

staff member whose

responsibility is that of a

scheduler.

This individual continuously develops and

updates activity schedules to

provide a

means

of tracking program work.

The resulting information is

then supplied to the

program

office

personnel, functional management, and

team members, and, last but

not least, is

presented

to the customer.

Note

that the activity scheduling is

probably the single most

important tool for

determining how

company

resources should be integrated so

that synergy is produced. Activity

schedules are

invaluable

for projecting time-phased resource

utilization requirements as well as

providing a

basis

for visually tracking

performance.

In

many cases, most programs

begin with the development of

schedules so that accurate

cost

estimates

can be made. The schedules

serve as master plans from

which both the customer

and

management

have an up-to-date picture of

operations.

24.2

Guidelines

for Preparation of

Schedules:

Regardless

of the projected use or complexity,

certain guidelines should be

followed in the

preparation

of schedules. These are as

follows:

�

Firstly,

all major events and

dates must be clearly

identified. If the customer supplies

a

statement

of work, those dates shown on the

accompanying schedules must be

included. If

for

any reason the customer's

milestone dates cannot be met, the

customer should be

notified

immediately.

�

The

exact sequence of work should be

defined through a network in

which

interrelationships

between events can be

identified.

�

Schedules

should be directly relatable to the

Work Breakdown Structure (WBS). If

the

Work

Breakdown Structure (WBS) is developed

according to a specific sequence of

work,

then

it becomes an easy task to

identify work sequences in

schedules using the

same

163

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

numbering

system as in the Work Breakdown Structure

(WBS). The minimum

requirement

should

be to show where and when all

tasks start and

finish.

�

All

schedules must identify the

time constraints and, if possible, should

identify those

resources

required for each

event.

Here

we see that although these

four guidelines relate to

schedule preparation, they do

not

define

how complex the schedules

should be. Before preparing

schedules, three questions

should

be considered:

�

How

many events or activities

should each network

have?

�

How

much of a detailed technical

breakdown should be

included?

�

Who

is the intended audience for this

schedule?

In

this regard, most organizations

develop multiple schedules:

summary schedules for

management

and

planners and detailed schedules for the

doers and lower-level control.

The detailed

schedules

may

be strictly for interdepartmental

activities. Program management must

approve all schedules

down

through the first three levels of the

work breakdown structure. For

lower-level schedules

(that

is,

detailed interdepartmental), program

management may or may not

request a sign of

approval.

The

need for two schedules is

clear. In larger complicated projects,

planning and status

review

by

different echelons are

facilitated by the use of detailed and

summary networks. Higher

levels

of

management can view the

entire project and the interrelationships

of major tasks

without

looking

into the detail of the individual

subtasks. Lower levels of

management and supervision

can

examine their parts of the

project in fine detail

without being distracted by those

parts of the

project

with which they have no

interface.

One

of the most difficult problems to

identify in schedules is a hedge

position. A

hedge position

is

a situation in which the contractor may

not be able to meet a

customer's milestone

date

without

incurring a risk, or may not

be able to meet activity requirements

following a milestone

date

because of contractual

requirements.

24.3

Preparation

Sequence of Schedules:

For

almost every activity detailed

schedules are prepared. It is the

responsibility of the program

office

to marry all of the detailed

schedules into one master

schedule to verify that all

activities

can

be completed as planned.

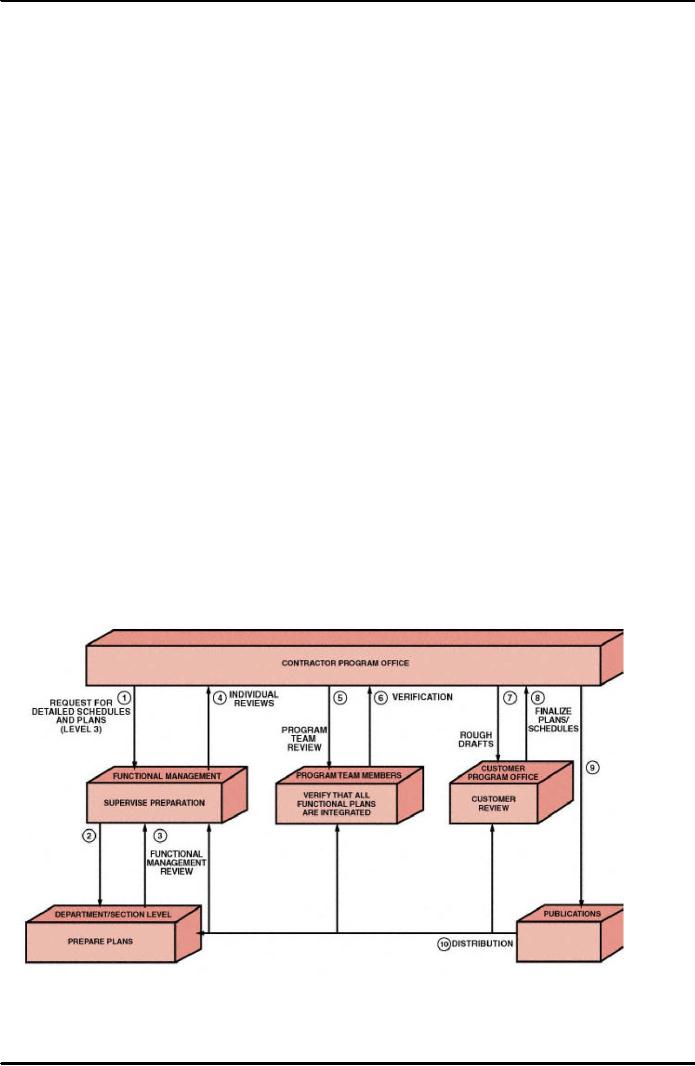

According

to the sequence, the program office

submits a request for detailed

schedules to the

functional

managers then prepare summary schedules,

detailed schedules, and, if time

permits,

interdepartmental

schedules. Each functional

manager then reviews his

schedules with the

program

office. The program office,

together with the functional

program team members,

integrates

all of the plans and schedules

and verifies that all

contractual dates can be

met.

Note

that before the schedules

are submitted to publications,

rough drafts of each

schedule and

plan

should be reviewed with the customer.

This procedure accomplishes the

following:

�

Verifies

that nothing has fallen

through the cracks

�

Prevents

immediate revisions to a published

document and can prevent

embarrassing

moments

�

Minimizes

production costs by reducing the number

of early revisions

�

Shows

customers early in the program

that you welcome their

help and input into

the

planning

phase

Once

the document is published, it should be

distributed to all program

office personnel,

functional

team members, functional

management, and the customer.

164

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

The

exact method of preparing the schedules

is usually up to the individual

performing the

activity.

However,

the program office must

approve all schedules. The

schedules are normally

prepared

in

a format that is suitable to

both the customer and contractor and is

easily understood by all.

The

schedules may then be used

in-house as well as for

customer review meetings, in

which

case

the contractor can "kill two

birds with one stone" by

tracking cost and performance on

the

original

schedules.

In

addition to the detailed schedules, the

program office, with input

provided by functional

management,

must develop organization

charts. The organizational

charts tell all

active

participants

in the project who has

responsibility for each

activity. The organizational

charts

display

the formal (and often the

informal) lines of

communication.

Linear

responsibility charts (LRCs) are

also established by the program office.

In spite of the

best

attempts by management, many

functions in an organization may

overlap between

functional

units.

The

management might also wish

to have the responsibility for a certain

activity given to a

functional

unit that normally would

not have that responsibility.

This is a common occurrence

on

short duration programs where management

desires to cut costs and red tape.

Importantly,

care must be taken that

project personnel do not forget the

reason why the

schedule

was

developed.

Summing

this up, the primary

objective of detailed schedules is

usually to coordinate

activities

into

a master plan in order to complete

the project with

the:

�

Best

time

�

Least

cost

�

Least

risk

The

objective can be constrained by the

following obvious

reasons:

�

Calendar

completion dates

�

Cash

or cash flow

restrictions

�

Limited

resources

�

Approvals

In

addition to this, there are

also secondary objectives of

scheduling:

�

Studying

alternatives

�

Developing

an optimal schedule

�

Using

resources effectively

�

Communicating

�

Refining

the estimating criteria

�

Obtaining

good project control

�

Providing

for easy revisions

24.4

Master

Production Scheduling:

We

know that master production

scheduling is not a new concept.

Earliest material

control

systems

used a "quarterly ordering

system" to produce a Master

Production Schedule (MPS) for

plant

production.

165

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

This

system uses customer order

backlogs to develop a production plan

over a three-month

period.

The production plan is then

exploded manually to determine

what parts must be

purchased

or manufactured at the proper time.

However, rapidly changing

customer

requirements

and fluctuating lead times, combined

with a slow response to

these changes, can

result

in the disruption of master production

scheduling.

24.5

Master

Production Schedule (MPS)

Definition:

Before

going into the details, it is

important to know what a

Master Production Schedule

(MPS)

is.

A Master

Production Schedule (MPS) is a

statement of what will be

made, how many

units

will

be made, and when they will

be made. It is a production plan,

not a sales plan. The

Master

Production

Schedule (MPS) considers the total

demand on a plant's resources,

including

finished

product sales, spare

(repair) part needs, and

interplant needs. The Master

Production

Schedule

(MPS) must also consider the

capacity of the plant and the requirements imposed

on

vendors.

Provisions are made in the

overall plan for each

manufacturing facility's operation.

All

planning

for materials, manpower, plant,

equipment, and financing for

the facility is driven by

the

master production

schedule.

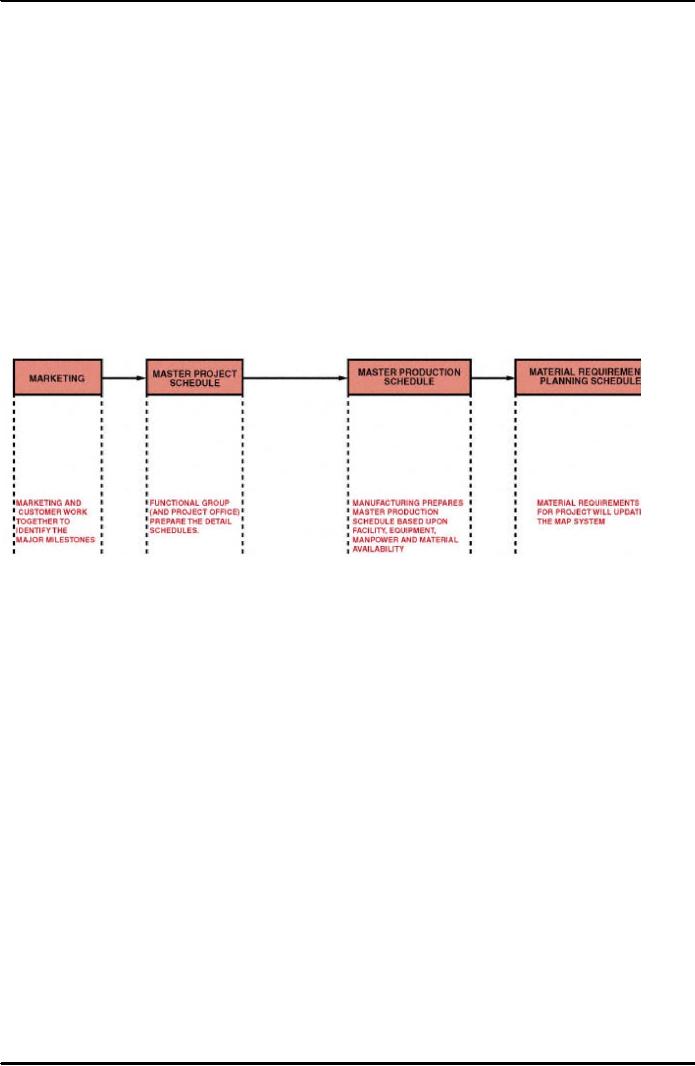

Figure

24.1: Material

Requirements Pl

166

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

under

severe scrutiny during the

1960s when the Department of Defense

required all contractors

to

submit detailed planning to

such extremes that many

organizations were wasting

talented

people

by having them serve as writers instead

of doers. Since then, because of the

complexity

of

large programs, requirements imposed on the program

plan have been eased.

In

case of large and often

complex programs, customers may

require a program plan

that

documents

all activities within the

program. The program plan

then serves as a guideline

for the

lifetime

of the program and may be revised as

often development programs require

more

revisions

to the program plan than

manufacturing or construction programs).

The program plan

provides

the following framework:

�

Eliminates

conflicts between functional

managers

�

Eliminates

conflicts between functional management

and program management

�

Provides

a standard communications tool throughout

the lifetime of the program. (It

should

be

geared to the work breakdown

structure.)

�

Provides

verification that the contractor

understands the customer's objectives

and

requirements

�

Provides

a means for identifying inconsistencies

in the planning phase

�

Provides

a means for early

identification of problem areas

and risks so that no

surprises

occur

downstream

Note

that the development of a program

plan can be time-consuming and

costly. The input

requirements

for the program plan depend on the

size of the project and the integration

of

resources

and activities. All levels of the

organization participate. The

upper levels provide

summary

information, and the lower levels

provide the details. The

program plan, like

activity

schedules,

does not preclude

departments from developing

their own planning.

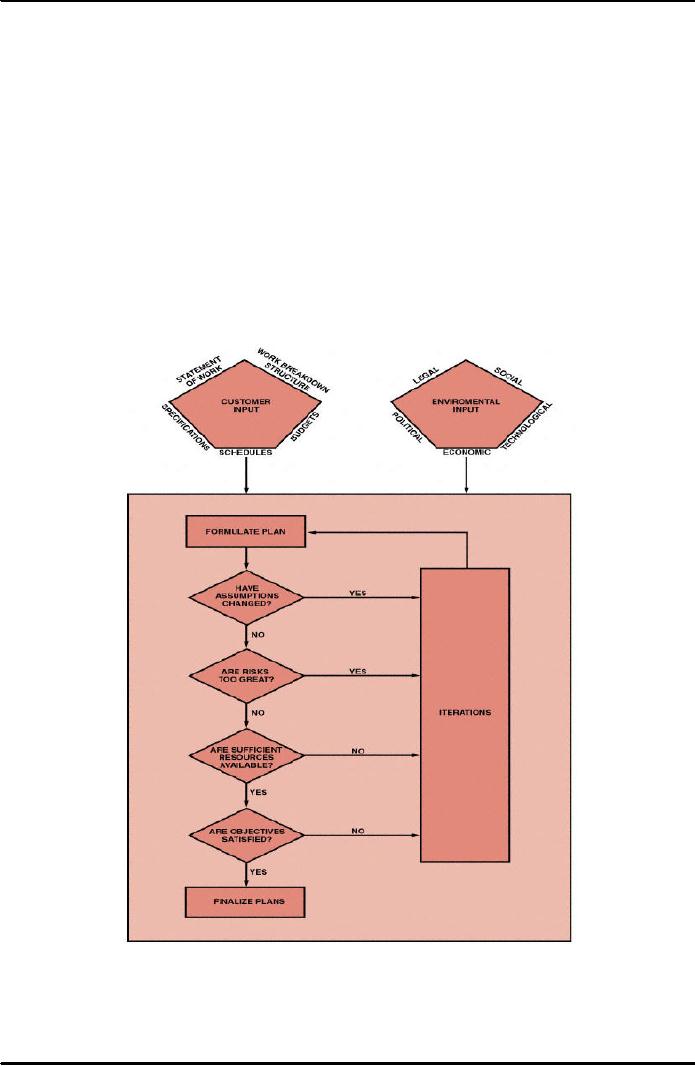

One

of the key features of the program

plan is that it must

identify how the company

resources

will

be integrated. Finalization of the

program is an iterative process

similar to the sequence of

events

for schedule preparation, shown in the

figure 24.2 below. Since the

program plan must

explain

the events in the figure, additional

iterations are required,

which can cause changes in

a

program.

Figure

24.2:

167

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

as

a cookbook for the duration of the

program by answering the following

questions for all

personnel

identified with the

program:

�

What

will be accomplished?

�

How

will it be accomplished?

�

Where

will it be accomplished?

�

When

will it be accomplished?

�

Why

will it be accomplished?

The

answers to these questions force

both the contractor and the customer to

take a hard look

at:

�

Program

requirements

�

Program

management

�

Program

schedules

�

Facility

requirements

�

Logistic

support

�

Financial

support

�

Manpower

and organization

Figure

24.3: Iterations

for the Planning

Process

In

addition to this, the program

plan is more than just a set

of instructions. It is an attempt to

eliminate

crisis by preventing anything from

''falling through the cracks." The

plan is

documented

and approved by both the customer

and the contractor to determine

what data, if

168

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

any,

are missing and the probable

resulting effect. As the program

matures, the program plan

is

revised

to account for new or missing data.

The most common reasons for

revising a plan are:

�

"Crashing"

activities to meet end

dates

�

Trade-off

decisions involving manpower, scheduling,

and performance

�

Adjusting

and leveling manpower

requests

Usually

the maturity of a program implies

that crisis will decrease.

Unfortunately, this is not

always

the

case.

The

makeup of the program plan may

vary from contractor to

contractor. Most program

plans

can

be subdivided into four main

sections:

i)

Introduction

ii)

Summary

and conclusions

iii)

Management

iv)

Technical

The

complexity of the information is usually

up to the discretion of the contractor,

provided that

customer

requirements, as may be specified in the

statement of work, are

satisfied.

To

begin with, the introductory

section contains

the definition of the program and the

major

parts

involved. If the program follows

another, or is an outgrowth of similar

activities, this is

indicated,

together with a brief summary of the

background and history behind the

project.

The

second section that is the

summary

and conclusion section

identifies the targets

and

objectives

of the program and includes the necessary

"lip service" on how

successful the

program

will be and how all problems

can be overcome. This section must

also include the

program

master schedule showing how

all projects and activities are

related. The total

program

master

schedule should include the

following:

�

An

appropriate scheduling system

(bar charts, milestone

charts, network, etc.)

�

A

listing of activities at the project

level or lower

�

The

possible interrelationships between activities

(can be accomplished by logic

networks,

critical

path networks, or PERT

networks)

�

Activity

time estimates (a natural

result of the item

above)

As

already mentioned, the summary and

conclusion chapter is usually the second

section in the

program

plan so that upper-level

customer management can have a complete

overview of the

program

without having to search

through the technical

information.

The

third section, that is the

management

section of the

program plan contains

procedures,

charts,

and schedules as

follows:

�

The

assignment of key personnel to the

program is indicated. This

usually refers only to the

program

office personnel and team members,

since under normal operations

these will be

the

only individuals interfacing

with customers.

�

Manpower,

planning, and training are

discussed to assure customers

that qualified people

will

be available from the functional

units.

�

A

linear responsibility chart might

also be included to identify to

customers the authority

relationships

that will exist in the

program.

169

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

There

exist some situations in

which the management section may be

omitted from the

proposal.

For a follow-up program, the

customer may not require

this section if management's

positions

are unchanged.

In

addition to this, the management

sections are also not

required if the management

information

was previously provided in the

proposal or if the customer and contractor

have

continuous

business dealings.

The

fourth section that is the

technical

section

may include as much as 75 to 90 percent

of the

program

plan, especially if the effort

includes research and development.

The technical section

may

require constant updating as the

program matures. The

following items can be included

as

part

of the technical section:

�

Detailed

breakdown of the charts and schedules

used in the program master

schedule,

possibly

including schedule/cost

estimates.

�

Listing

of the testing to be accomplished for

each activity. (It is best

to include the exact

testing

matrices.)

�

Procedures

for accomplishment of testing. This

might also include a

description of the key

elements

in the operations or manufacturing plans as well as a

listing of the facility

and

logistic

requirements.

�

Identification

of materials and material specifications.

(This might also include

system

specifications.)

�

An

attempt to identify the risks associated

with specific technical requirements

(not

commonly

included). This assessment

tends to scare management personnel

who are

unfamiliar

with the technical procedures, so it

should be omitted if at all

possible.

Therefore,

the program plan contains a description

of all phases of the program.

For many

programs,

especially large ones,

detailed planning is required

for all major events and

activities.

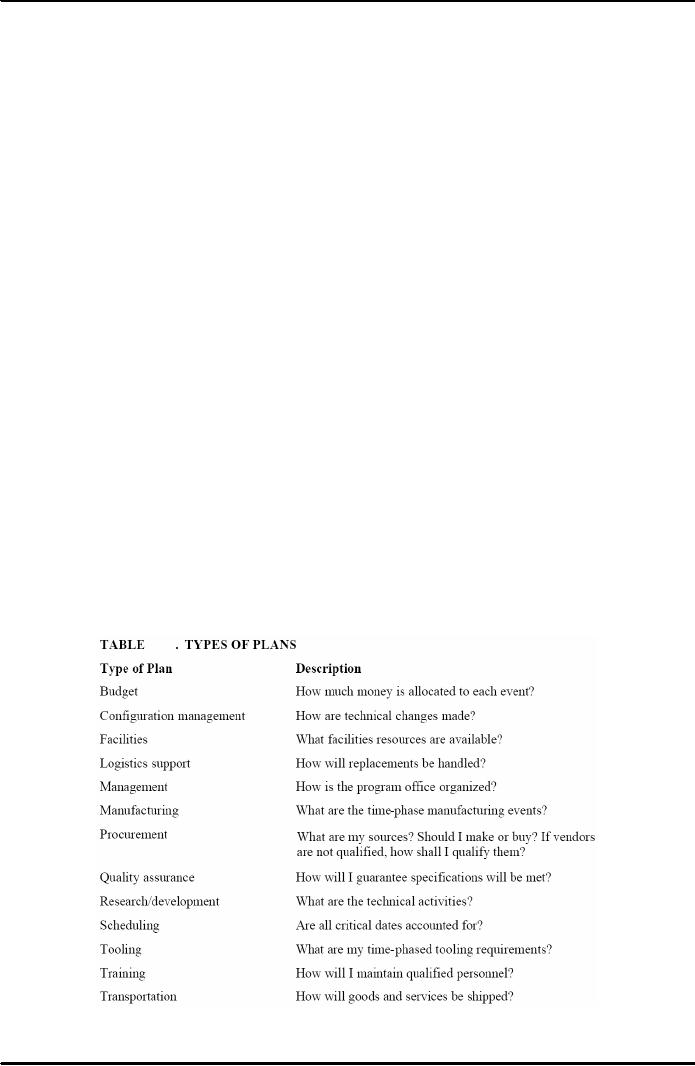

The

following Table 24.1

identifies the type of individual plans

that may be required in place

of

a

(total) program plan.

However, the amount of detail must be

controlled, for too

much

paperwork

can easily inhibit

successful management of a

program.

Table

24.1: Types

of Plans

170

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

Once

agreed on by the contractor and customer, the

program plan is then used to

provide

program

direction. This is shown in the figure

24.4 below. If the program

plan is written

clearly,

then

any functional manager or supervisor

should be able to identify

what is expected of him.

Note

that the program plan should

be distributed to each member of the

program team, all

functional

managers and supervisors interfacing with

the program, and all key

functional

personnel.

The program plan does

not contain all of the

answers, for if it did, there

would be no

need

for a program office. The

plan serves merely as a

guide.

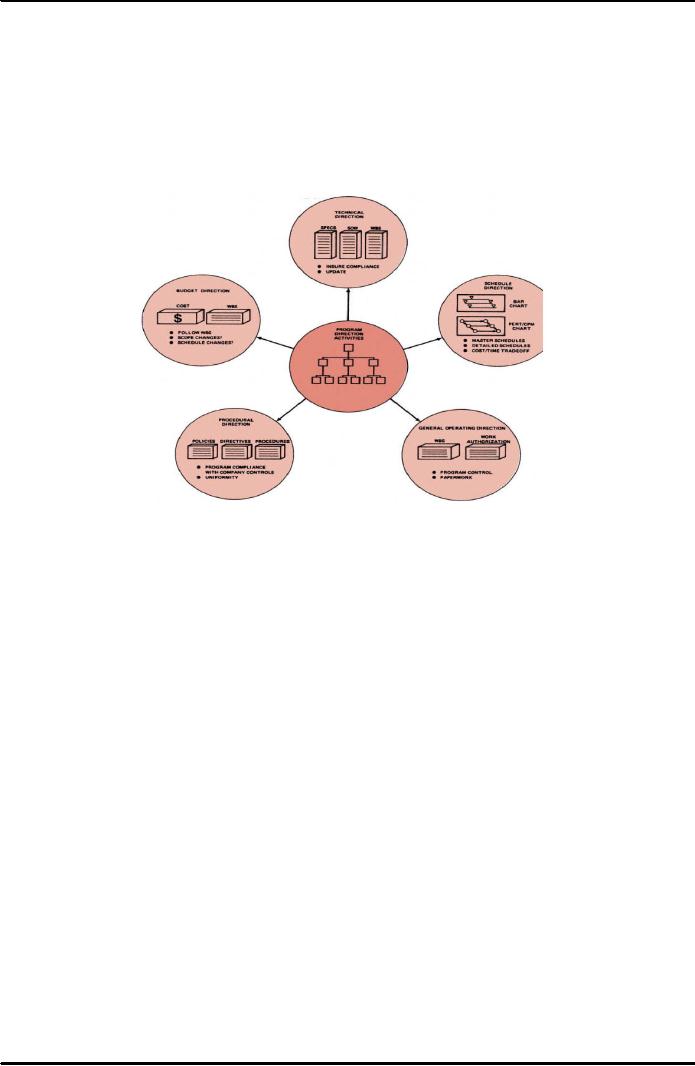

Figure

24.4: Program

Direction Activities

Here

we conclude with a final note

that the program plan may be

specified contractually to

satisfy

certain requirements as identified in the

customer's statement of work.

The contractor

retains

the right to decide how to accomplish

this, unless, of course,

this is also identified in

the

Statement

of Work (SOW). If the Statement of

Work (SOW) specifies that

quality assurance

testing

will be accomplished on fifteen end-items

from the production line,

then fifteen is the

minimum

number that must be tested.

The program plan may show

that twenty-five items are

to

be

tested. If the contractor develops cost

overrun problems, he may wish to

revert to the

Statement

of Work (SOW) and test only

fifteen items. Contractually, he may do

this without

informing

the customer. In most cases, however, the

customer is notified, and the program

is

revised.

171

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Broad Contents, Functions of Management

- CONCEPTS, DEFINITIONS AND NATURE OF PROJECTS:Why Projects are initiated?, Project Participants

- CONCEPTS OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT:THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT SYSTEM, Managerial Skills

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT METHODOLOGIES AND ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES:Systems, Programs, and Projects

- PROJECT LIFE CYCLES:Conceptual Phase, Implementation Phase, Engineering Project

- THE PROJECT MANAGER:Team Building Skills, Conflict Resolution Skills, Organizing

- THE PROJECT MANAGER (CONTD.):Project Champions, Project Authority Breakdown

- PROJECT CONCEPTION AND PROJECT FEASIBILITY:Feasibility Analysis

- PROJECT FEASIBILITY (CONTD.):Scope of Feasibility Analysis, Project Impacts

- PROJECT FEASIBILITY (CONTD.):Operations and Production, Sales and Marketing

- PROJECT SELECTION:Modeling, The Operating Necessity, The Competitive Necessity

- PROJECT SELECTION (CONTD.):Payback Period, Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

- PROJECT PROPOSAL:Preparation for Future Proposal, Proposal Effort

- PROJECT PROPOSAL (CONTD.):Background on the Opportunity, Costs, Resources Required

- PROJECT PLANNING:Planning of Execution, Operations, Installation and Use

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Outside Clients, Quality Control Planning

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Elements of a Project Plan, Potential Problems

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Sorting Out Project, Project Mission, Categories of Planning

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Identifying Strategic Project Variables, Competitive Resources

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Responsibilities of Key Players, Line manager will define

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):The Statement of Work (Sow)

- WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE:Characteristics of Work Package

- WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE:Why Do Plans Fail?

- SCHEDULES AND CHARTS:Master Production Scheduling, Program Plan

- TOTAL PROJECT PLANNING:Management Control, Project Fast-Tracking

- PROJECT SCOPE MANAGEMENT:Why is Scope Important?, Scope Management Plan

- PROJECT SCOPE MANAGEMENT:Project Scope Definition, Scope Change Control

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Historical Evolution of Networks, Dummy Activities

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Slack Time Calculation, Network Re-planning

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Total PERT/CPM Planning, PERT/CPM Problem Areas

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION:GLOBAL PRICING STRATEGIES, TYPES OF ESTIMATES

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.):LABOR DISTRIBUTIONS, OVERHEAD RATES

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.):MATERIALS/SUPPORT COSTS, PRICING OUT THE WORK

- QUALITY IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Value-Based Perspective, Customer-Driven Quality

- QUALITY IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT (CONTD.):Total Quality Management

- PRINCIPLES OF TOTAL QUALITY:EMPOWERMENT, COST OF QUALITY

- CUSTOMER FOCUSED PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Threshold Attributes

- QUALITY IMPROVEMENT TOOLS:Data Tables, Identify the problem, Random method

- PROJECT EFFECTIVENESS THROUGH ENHANCED PRODUCTIVITY:Messages of Productivity, Productivity Improvement

- COST MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL IN PROJECTS:Project benefits, Understanding Control

- COST MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL IN PROJECTS:Variance, Depreciation

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT THROUGH LEADERSHIP:The Tasks of Leadership, The Job of a Leader

- COMMUNICATION IN THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Cost of Correspondence, CHANNEL

- PROJECT RISK MANAGEMENT:Components of Risk, Categories of Risk, Risk Planning

- PROJECT PROCUREMENT, CONTRACT MANAGEMENT, AND ETHICS IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Procurement Cycles