|

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

LESSON

11

PROJECT

SELECTION

Broad

Contents

Introduction

Project

decisions

Types

of project selection models

Criteria

for choosing project

model

The

nature of project selection models

Numeric

and non-numeric models

11.1

Introduction:

Project

selection is the process

of choosing a project or set of

projects to be implemented

by

the

organization. Since projects

in general require a substantial investment in

terms of money

and

resources, both of which are

limited, it is of vital importance

that the projects that an

organization

selects provide good returns on the

resources and capital invested.

This

requirement

must be balanced with the need

for an organization to move

forward and develop.

The

high level of uncertainty in the modern

business environment has

made this area of

project

management

crucial to the continued success of an

organization with the difference

between

choosing

good projects and poor projects literally

representing the difference between

operational

life and death.

Because

a successful model must capture

every critical aspect of the

decision, more complex

decisions

typically require more sophisticated models.

"There is a simple solution to

every

complex

problem; unfortunately, it is wrong".

This reality creates a major

challenge for tool

designers.

Project decisions are often high-stakes,

dynamic decisions with complex

technical

issues--precisely

the kinds of decisions that are

most difficult to

model:

�

Project

selection decisions are high-stakes because of

their strategic implications.

The

projects

a company chooses can define the products

it supplies, the work it does, and

the

direction

it takes in the marketplace. Thus, project decisions

can impact every

business

stakeholder,

including customers, employees, partners,

regulators, and shareholders. A

sophisticated

model may be needed to capture strategic

implications.

�

Project

decisions are dynamic because a

project may be conducted over several

budgeting

cycles,

with repeated opportunities to

slow, accelerate, re-scale, or

terminate the project.

Also,

a successful project may produce

new assets or products that

create time-varying

financial

returns and other impacts over

many years. A more sophisticated model is

needed

to

address dynamic impacts.

�

Project

decisions typically produce many

different types of impacts on the

organization. For

example,

a project might increase revenue or

reduce future costs. It

might impact how

customers

or investors perceive the organization. It

might provide new capability

or

learning,

important to future success.

Making good choices requires

not just estimating

the

financial

return on investment; it requires

understanding all of the ways that

projects add

value.

A more sophisticated model is needed to

account for all of the

different types of

potential

impacts that project selection decisions

can create.

89

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

11.2

Project

Decisions:

Project

decisions often entail risk

and uncertainty. The

significance of a project risk

depends on

the

nature of that risk and on the other

risks that the organization is taking. A

more sophisticated

model

is needed to correctly deal

with risk and

uncertainty.

Project

selection is the process of evaluating

individual projects or groups of projects, and

then

choosing

to implement some set of them so

that the objectives of the parent

organization will be

achieved.

This same systematic process

can be applied to any area

of the organization's

business

in which choices must be

made between competing alternatives.

For example:

�

A

manufacturing firm can use

evaluation/selection techniques to choose

which machine to

adopt

in a part-fabrication process.

�

A

television station can

select which of several syndicated comedy

shows to rerun in its

7:30

p.m. weekday time-slot

�

A

construction firm can select

the best subset of a large

group of potential projects on

which

to

bid

�

A

hospital can find the best

mix of psychiatric, orthopedic,

obstetric, and other beds

for a

new

wing.

Each

project will have different

costs, benefits, and risks. Rarely

are these known with

certainty.

In

the face of such differences, the

selection of one project out of a

set is a difficult task.

Choosing

a number of different projects, a portfolio, is

even more complex. In the

following

sections,

we discuss several techniques that can be

used to help senior managers

select projects.

Project

selection is only one of many decisions

associated with project

management.

To

deal with all of these

problems, we use decision

aiding models. We

need such models

because

they abstract the relevant

issues about a problem from

the plethora of detail in

which

the

problem is embedded. Reality is

far too complex to deal

with in its entirety. An

"idealist" is

needed

to strip away almost all the

reality from a problem,

leaving only the aspects of the

"real"

situation

with which he or she wishes

to deal. This process of

carving away the unwanted

reality

from

the bones of a problem is called

modeling

the problem. The

idealized version of the

problem

that results is called a

model.

The

model represents the problem's

structure,

its

form. Every problem has a

form, though often

we

may not understand a problem

well enough to describe its

structure. We will use

many

models

in this book--graphs, analogies, diagrams, as

well as flow

graph and network models

to

help

solve scheduling problems, and symbolic

(mathematical)

models for a number of purposes.

Models

may be quite simple to understand, or

they may be extremely

complex. In general,

introducing

more reality into a model

tends to make the model more

difficult to manipulate. If

the

input data for a model

are not known precisely, we

often use probabilistic

information; that

is,

the model is said to be stochastic

rather

than deterministic.

Again,

in general, stochastic models are more

difficult to manipulate. We live in the

midst of

what

has been called the

"knowledge explosion." We frequently

hear comments such as

"90

percent

of all we know about physics

has been discovered since

Albert Einstein published

his

original

work on special relativity"; and

"80 percent of what we know

about the human body

has

been discovered in the past 50 years." In

addition, evidence is cited to show that

knowledge

is

growing exponentially.

Such

statements emphasize the importance of

the management

of change. To

survive, firms

should

develop strategies for

assessing and reassessing the use of

their resources.

Every

allocation

of resources is an investment in the

future. Because of the complex nature of

most

strategies,

many of these investments are in

projects.

To

cite one of many possible examples, special

visual effects accomplished through

computer

animation

are common in the movies and television

shows we watch daily. A few

years ago

90

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

they

were unknown. When the capability was in

its idea stage, computer

companies as well as

the

firms producing movies and

television shows faced the decision

whether or not to invest

in

the

development of these techniques.

Obviously valuable as the idea

seems today, the choice

was

not quite so clear a decade

ago when an entertainment company

compared investment in

computer

animation to alternative investments in a

new star, a new rock group,

or a new theme

park.

The

proper choice of investment projects is

crucial to the long-run survival of

every firm. Daily

we

witness the results of both good

and bad investment choices. In

our daily newspapers

we

read

of Cisco System's decision to purchase

firms that have developed

valuable communication

network

software rather than to

develop its own software. We

read of Procter and Gamble's

decision

to invest heavily in marketing

its products on the Internet; British

Airways' decision to

purchase

passenger planes from Airbus

instead of from its traditional

supplier, Boeing; or

problems

faced by school systems when they update

student computer labs--should they

invest

in

Windows-based systems or stick with

their traditional choice, Apple�.

But can such

important

choices be made rationally?

Once made, do they ever

change, and if so, how?

These

questions

reflect the need for

effective selection models.

Within

the limits of their capabilities,

such models can be used to

increase profits,

select

investments

for limited capital

resources, or improve the competitive

position of the

organization.

They can be used for

ongoing evaluation as well as

initial selection, and thus, are

a

key to the allocation and

reallocation of the organization's scarce

resources.

11.2.1

Modeling:

A

model is an object or concept, which

attempts to capture certain aspects of

the real

world.

The purpose of models can

vary widely, they can be

used to test ideas, to

help

teach

or explain new concepts to

people or simply as decorations. Since the

uses that

models

can be put are so many it is

difficult to find a definition

that is both clear and

conveys

all the meanings of the word. In the

context of project selection the

following

definition

is useful:

"A

model is an explicit statement of our

image of reality. It is a representation of

the

relevant

aspects of the decision with

which we are concerned. It represents the

decision

area

by structuring and formalizing the

information we possess about the

decision and,

in

doing so, presents reality

in a simplified organized form. A model,

therefore,

provides

us with an abstraction of a more complex

reality".

(Cooke and Slack,

1991)

When

project selection models are seen

from this perspective it is clear that

the need for

them

arises from the fact that it

is impossible to consider the environment,

within which

a

project will be implemented, in

its entirety. The challenge

for a good project

selection

model

is therefore clear. It must

balance the need to keep enough

information from the

real

world to make a good choice with the

need to simplify the situation

sufficiently to

make

it possible to come to a conclusion in a

reasonable length of

time.

11.3

Criteria

for Choosing Project

Model:

When

a firm chooses a project selection

model, the following criteria,

based on Souder (1973),

are

most important:

1.

Realism:

The

model should reflect the

reality of the manager's decision

situation, including the

multiple

objectives of both the firm and

its managers. Without a common

measurement

system,

direct comparison of different projects is

impossible.

For

example, Project A may strengthen a

firm's market share by

extending its

facilities,

and

Project B might improve its

competitive position by strengthening

its technical

staff.

Other things being equal,

which is better? The model

should take into account

the

91

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

realities

of the firm's limitations on facilities,

capital, personnel, and so forth.

The

model

should also include factors

that reflect project risks,

including the technical risks

of

performance, cost, and time as

well as the market risks of customer

rejection and

other

implementation risks.

2.

Capability:

The

model should be sophisticated enough to

deal with multiple time

periods, simulate

various

situations both internal and

external to the project (for

example, strikes, interest

rate

changes), and optimize the

decision. An optimizing model

will make the

comparisons

that management deems

important, consider major risks and constraints

on

the

projects, and then select the best

overall project or set of

projects.

3.

Flexibility:

The

model should give valid

results within the range of conditions

that the firm might

experience.

It should have the ability to be easily

modified, or to be self-adjusting

in

response

to changes in the firm's environment;

for example, tax laws

change, new

technological

advancements alter risk

levels, and, above all, the

organization's goals

change.

4.

Ease

of Use:

The

model should be reasonably convenient,

not take a long time to

execute, and be

easy

to use and understand. It should not

require special interpretation, data

that are

difficult

to acquire, excessive personnel, or unavailable

equipment. The

model's

variables

should also relate

one-to-one with those

real-world parameters, the

managers

believe

significant to the project. Finally, it

should be easy to simulate the

expected

outcomes

associated with investments in different

project portfolios.

5.

Cost:

Data

gathering and modeling costs

should be low relative to the

cost of the

project

and

must surely be less than the

potential benefits of the project. All

costs should be

considered,

including the costs of data

management and of running the

model.

Here,

we would also add a sixth

criterion:

6.

Easy

Computerization:

It

should be easy and convenient to gather

and store the information in a

computer

database,

and to manipulate data in the model

through use of a widely

available,

standard

computer package such as Excel,

Lotus 1-2-3, Quattro Pro, and

like programs.

The

same ease and convenience should

apply to transferring the information to

any

standard

decision support system.

In

what follows, we first

examine fundamental types of project

selection models and the

characteristics

that make any model more or

less acceptable. Next we consider

the

limitations,

strengths, and weaknesses of

project selection models, including

some

suggestions

of factors to consider when making a

decision about which, if

any, of the

project

selection models to use. We then

discuss the problem of selecting projects

when

high

levels of uncertainty about

outcomes, costs, schedules, or

technology are

present,

as

well as some ways of managing the risks

associated with the

uncertainties.

Finally,

we comment on some special aspects of the

information base required

for

project

selection. Then we turn our

attention to the selection of a set of projects to

help

the

organization achieve its goals and

illustrate this with a

technique called the Project

Portfolio

Process. We

finish the chapter with a discussion of

project proposals.

11.4

The

Nature of Project Selection

Models:

92

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

There

are two basic types of

project selection models, numeric

and

nonnumeric. Both

are

widely

used. Many organizations use

both at the same time, or

they use models that

are

combinations

of the two. Nonnumeric models, as the

name implies, do not use

numbers as

inputs.

Numeric models do, but the

criteria being measured may

be either objective or

subjective.

It is important to remember that the

qualities

of

a project may be represented

by

numbers,

and that subjective

measures

are not necessarily less

useful or reliable than

objective

measures.

Before

examining specific kinds of models

within the two basic types,

let us consider just

what

we

wish the model to do for us,

never forgetting two

critically important, but

often overlooked

facts.

�

Models

do not make decisions--people

do. The manager, not the

model, bears

responsibility

for the decision. The

manager may "delegate" the

task of making the

decision

to

a model, but the responsibility cannot be

abdicated.

�

All

models, however sophisticated, are only

partial representations of the reality

they are

meant

to reflect. Reality is far

too complex for us to capture more

than a small fraction of

it

in

any model. Therefore, no

model can yield an optimal

decision except within its

own,

possibly

inadequate, framework.

We

seek a model to assist us in

making project selection decisions. This

model should possess

the

characteristics discussed previously and,

above all, it should evaluate

potential projects by

the

degree to which they will

meet the firm's objectives. To construct

a selection/evaluation

model,

therefore, it is necessary to develop a

list of the firm's

objectives.

A

list of objectives should be

generated by the organization's top

management. It is a direct

expression

of organizational philosophy and policy.

The list should go beyond

the typical

clich�s

about "survival" and "maximizing

profits," which are

certainly real goals but are

just as

certainly

not the only goals of the firm.

Other objectives might

include maintenance of share of

specific

markets, development of an improved image

with specific clients or

competitors,

expansion

into a new line of business,

decrease in sensitivity to business

cycles, maintenance of

employment

for specific categories of

workers, and maintenance of system

loading at or above

some

percent of capacity, just to mention a

few.

A

model of some sort is implied by

any conscious decision. The

choice between two or more

alternative

courses of action requires reference to

some objective(s), and the choice is

thus,

made

in accord with some,

possibly subjective, "model." Since the

development of computers

and

the establishment of operations research as an

academic subject in the mid-1950s, the

use of

formal,

numeric models to assist in decision

making has expanded. Many of

these models use

financial

metrics such as profits and/or

cash flow to measure the "correctness" of

a managerial

decision.

Project selection decisions are no

exception, being based

primarily on the degree to

which

the financial goals of the organization

are met. As we will see

later, this stress on

financial

goals, largely to the exclusion of other

criteria, raises some

serious problems for the

firm,

irrespective of whether the firm is

for profit or

not-for-profit.

When

the list of objectives has

been developed, an additional

refinement is recommended.

The

elements

in the list should be weighted.

Each

item is added to the list

because it represents a

contribution

to the success of the organization, but

each item does not

make an equal

contribution.

The weights reflect

different degrees of contribution

each element makes in

accomplishing

a set of goals.

Once

the list of goals has been

developed, one more task remains. The

probable contribution of

each

project to each of the goals should be

estimated. A project is selected or rejected

because it

is

predicted to have certain outcomes if

implemented.

93

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

These

outcomes are expected to contribute to

goal achievement. If the estimated level of

goal

achievement

is sufficiently large, the project is

selected. If not, it is rejected.

The

relationship between the project's expected

results and the organization's goals must

be

understood.

In general, the kinds of information

required to evaluate a project

can be listed

under

production, marketing, financial,

personnel, administrative, and other such

categories.

The

following table 11.1 is a

list of factors that contribute,

positively or negatively, to

these

categories.

In

order to give focus to this

list, we assume that the

projects in question involve the

possible

substitution

of a new production process

for an existing one. The

list is meant to be

illustrative.

It

certainly is not

exhaustive.

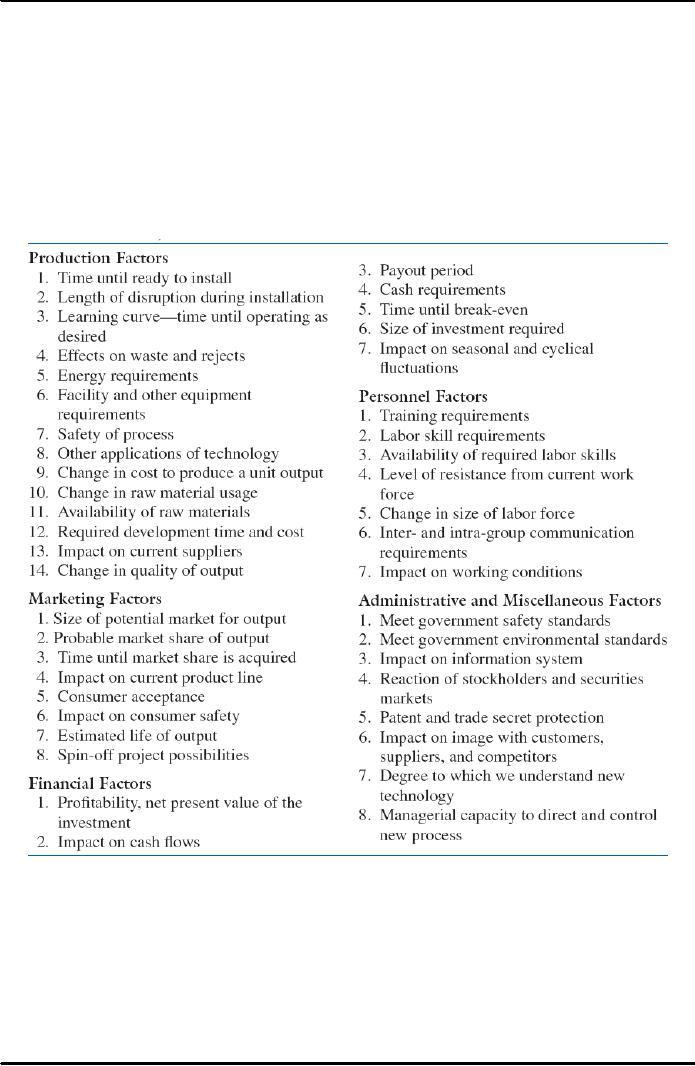

Table

11.1: Factors Contributing to Various

Organizational Categories

Some

factors in this list have a one-time

impact and some recur.

Some are difficult to

estimate

and

may be subject to considerable error. For

these, it is helpful to identify a

range

of

uncertainty.

In

addition, the factors may occur at

different times.

And

some factors may have thresholds,

critical

values above or below which we might

wish to

reject

the project. We will deal in more

detail with these issues

later in this chapter.

94

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

Clearly,

no single project decision

needs to include all these

factors. Moreover, not only is

the

list

incomplete, it also contains redundant

items. Perhaps more important, the factors

are not at

the

same level of generality:

profitability

and

impact

on organizational image both

affect the

overall

organization, but impact

on working conditions is more

oriented to the production

system.

Nor are all elements of

equal importance.

Change

in production cost is

usually considered more important than

impact

on current

suppliers.

Shortly,

we will consider the problem of

generating an acceptable list of factors

and

measuring

their relative importance. At

that time we will discuss

the creation of a Decision

Support

System (DSS) for project

evaluation and selection.

The

same subject will arise once

more in the next lecture(s) when we consider

project auditing,

evaluation,

and termination.

Although

the process of evaluating a potential

project is time-consuming and difficult,

its

importance

cannot be overstated. A major consulting

firm has argued (Booz,

Allen, and

Hamilton,

1966) that the primary cause

for the failure of Research

and Development (R and

D)

projects

is insufficient care in evaluating the

proposal before the expenditure of funds.

What is

true

for such projects also

appears to be true for other

kinds of projects, and it is clear

that

product

development projects are more successful

if they incorporate user

needs and satisfaction

in

the design process (Matzler and

Hinterhuber, 1998). Careful analysis of a

potential project is

a

sine

qua non for

profitability in the construction

business. There are many

horror stories

(Meredith,

1981) about firms that

undertook projects for the installation

of a computer

information

system without sufficient analysis of the

time, cost, and disruption

involved.

Later,

we will consider the problem of

conducting an evaluation under

conditions of uncertainty

about

the outcomes associated with a

project. Before dealing with

this problem, however,

it

helps

to examine several different

evaluation/selection models and consider their

strengths and

weaknesses.

Recall that the problem of choosing the

project selection model itself

will also be

discussed

later.

11.5

Types

of Project Selection Models:

Of

the two basic types of selection models

(numeric and nonnumeric), nonnumeric

models are

older

and simpler and have only a few

subtypes to consider. We examine them

first.

�

Non-Numeric

Models:

These

include the following:

1.

The Sacred

Cow:

In

this case the project is

suggested by a senior and powerful

official in the

organization.

Often the project is initiated

with a simple comment such

as, "If you have

a

chance, why don't you

look into . . .," and there

follows an undeveloped idea

for a

new

product, for the development of a

new market, for the design and

adoption of a

global

database and information system, or

for some other project

requiring an

investment

of the firm's resources. The

immediate result of this

bland statement is the

creation

of a "project" to investigate whatever

the boss has

suggested.

The

project is "sacred" in the sense

that it will be maintained

until successfully

concluded,

or until the boss, personally,

recognizes the idea as a failure

and

terminates

it.

2.

The

Operating Necessity:

If

a flood is threatening the plant, a

project to build a protective

dike does not

require

much formal evaluation,

which is an example of this

scenario. XYZ

Steel

Corporation has used this

criterion (and the following

criterion also) in

evaluating

potential projects. If the project is

required in order to keep the

95

Project

Management MGMT627

VU

system

operating, the primary question

becomes: Is the system worth

saving at

the

estimated cost of the project? If the

answer is yes, project costs

will be

examined

to make sure they are

kept as low as is consistent

with project

success,

but the project will be

funded.

3.

The

Competitive Necessity:

Using

this criterion, XYZ Steel undertook a

major plant rebuilding

project in

the

late 1960s in its steel bar

manufacturing facilities near

Chicago. It had

become

apparent to XYZ's management that the

company's bar mill

needed

modernization

if the firm was to maintain

its competitive position in

the

Chicago

market area. Although the

planning process for the

project was quite

sophisticated,

the decision to undertake the project

was based on a desire

to

maintain

the company's competitive position in

that market.

In

a similar manner, many business

schools are restructuring

their

undergraduate

and Masters in Business Administration (MBA) programs

to

stay

competitive with the more forward

looking schools. In large

part, this

action

is driven by declining numbers of

tuition paying students and

the need to

develop

stronger programs to attract them.

Investment

in an operating

necessity project

takes precedence over

a

competitive

necessity project,

but both types of projects may

bypass the more

careful

numeric analysis used for projects

deemed to be less urgent or

less

important

to the survival of the firm.

4.

The

Product Line Extension:

In

this case, a project to

develop and distribute new products

would be judged

on

the degree to which it fits the

firm's existing product

line, fills a gap,

strengthens

a weak link, or extends the

line in a new, desirable

direction.

Sometimes

careful calculations of profitability

are not required.

Decision

makers

can act on their beliefs

about what will be the

likely impact on the

total

system

performance if the new product is added

to the line.

5.

Comparative

Benefit Model:

For

this situation, assume that

an organization has many projects to

consider,

perhaps

several dozen. Senior management

would like to select a

subset of the

projects

that would most benefit the

firm, but the projects do not

seem to be

easily

comparable. For example, some projects

concern potential new

products,

some

concern changes in production

methods, others concern

computerization

of

certain records, and still

others cover a variety of

subjects not easily

categorized

(e.g., a proposal to create a daycare

center for employees with

small

children).

The

organization has no formal method of

selecting projects, but members of

the

selection committee think that some

projects will benefit the firm more

than

others,

even if they have no precise way to

define or measure

"benefit."

The

concept of comparative benefits, if

not a formal model, is

widely adopted

for

selection decisions on all sorts of projects.

Most United Way

organizations

use

the concept to make decisions about which

of several social programs to

fund.

Senior management of the funding

organization then examines

all

projects

with positive recommendations and

attempts to construct a portfolio

that

best fits the organization's

aims and its budget.

96

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION TO PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Broad Contents, Functions of Management

- CONCEPTS, DEFINITIONS AND NATURE OF PROJECTS:Why Projects are initiated?, Project Participants

- CONCEPTS OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT:THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT SYSTEM, Managerial Skills

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT METHODOLOGIES AND ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES:Systems, Programs, and Projects

- PROJECT LIFE CYCLES:Conceptual Phase, Implementation Phase, Engineering Project

- THE PROJECT MANAGER:Team Building Skills, Conflict Resolution Skills, Organizing

- THE PROJECT MANAGER (CONTD.):Project Champions, Project Authority Breakdown

- PROJECT CONCEPTION AND PROJECT FEASIBILITY:Feasibility Analysis

- PROJECT FEASIBILITY (CONTD.):Scope of Feasibility Analysis, Project Impacts

- PROJECT FEASIBILITY (CONTD.):Operations and Production, Sales and Marketing

- PROJECT SELECTION:Modeling, The Operating Necessity, The Competitive Necessity

- PROJECT SELECTION (CONTD.):Payback Period, Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

- PROJECT PROPOSAL:Preparation for Future Proposal, Proposal Effort

- PROJECT PROPOSAL (CONTD.):Background on the Opportunity, Costs, Resources Required

- PROJECT PLANNING:Planning of Execution, Operations, Installation and Use

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Outside Clients, Quality Control Planning

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Elements of a Project Plan, Potential Problems

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Sorting Out Project, Project Mission, Categories of Planning

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Identifying Strategic Project Variables, Competitive Resources

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):Responsibilities of Key Players, Line manager will define

- PROJECT PLANNING (CONTD.):The Statement of Work (Sow)

- WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE:Characteristics of Work Package

- WORK BREAKDOWN STRUCTURE:Why Do Plans Fail?

- SCHEDULES AND CHARTS:Master Production Scheduling, Program Plan

- TOTAL PROJECT PLANNING:Management Control, Project Fast-Tracking

- PROJECT SCOPE MANAGEMENT:Why is Scope Important?, Scope Management Plan

- PROJECT SCOPE MANAGEMENT:Project Scope Definition, Scope Change Control

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Historical Evolution of Networks, Dummy Activities

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Slack Time Calculation, Network Re-planning

- NETWORK SCHEDULING TECHNIQUES:Total PERT/CPM Planning, PERT/CPM Problem Areas

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION:GLOBAL PRICING STRATEGIES, TYPES OF ESTIMATES

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.):LABOR DISTRIBUTIONS, OVERHEAD RATES

- PRICING AND ESTIMATION (CONTD.):MATERIALS/SUPPORT COSTS, PRICING OUT THE WORK

- QUALITY IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Value-Based Perspective, Customer-Driven Quality

- QUALITY IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT (CONTD.):Total Quality Management

- PRINCIPLES OF TOTAL QUALITY:EMPOWERMENT, COST OF QUALITY

- CUSTOMER FOCUSED PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Threshold Attributes

- QUALITY IMPROVEMENT TOOLS:Data Tables, Identify the problem, Random method

- PROJECT EFFECTIVENESS THROUGH ENHANCED PRODUCTIVITY:Messages of Productivity, Productivity Improvement

- COST MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL IN PROJECTS:Project benefits, Understanding Control

- COST MANAGEMENT AND CONTROL IN PROJECTS:Variance, Depreciation

- PROJECT MANAGEMENT THROUGH LEADERSHIP:The Tasks of Leadership, The Job of a Leader

- COMMUNICATION IN THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Cost of Correspondence, CHANNEL

- PROJECT RISK MANAGEMENT:Components of Risk, Categories of Risk, Risk Planning

- PROJECT PROCUREMENT, CONTRACT MANAGEMENT, AND ETHICS IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT:Procurement Cycles