|

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

09

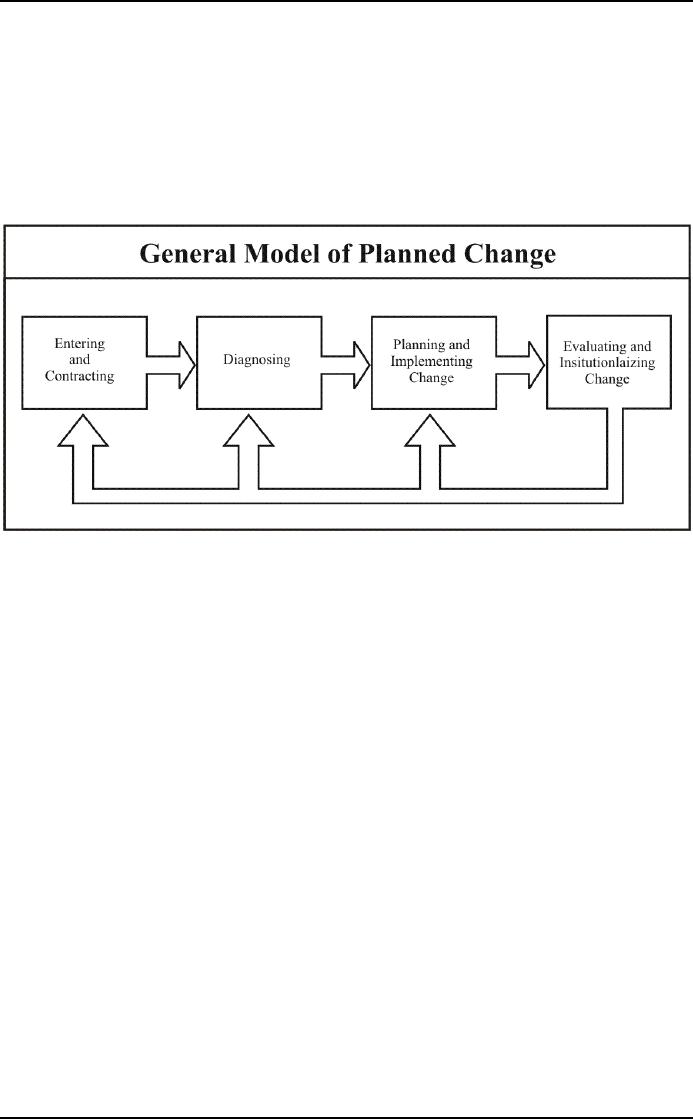

General

Model of Planned

Change

The

three theories of planned change in

organizations described above--Lewin's

change model, the action

research

model, and contemporary adaptations to the action

research model--suggest a general

framework

for

planned change, as shown in Fig. 10.

The framework describes the

four basic activities that

practitioners

and

organization members jointly carry

out in organization development. The

arrows connecting the

different

activities in the model show the typical sequence of

events, from entering and contracting,

to

diagnosing,

to planning and implementing change, to

evaluating and institutionalizing change.

The lines

connecting

the activities emphasize that organizational

change is not a straightforward, linear

process but

involves

considerable overlap and feedback

among the activities.

Figure:

08

Entering

and Contracting:

The

first set of activities in planned change

concerns entering and contracting. Those

events help managers

decide

whether they want to engage further in a planned

change program and to commit resources to

such

a

process. Entering an organization

involves gathering initial data to

understand the problems facing the

organization

or the positive opportunities for

inquiry. Once this information is

collected, the problems or

opportunities

are discussed with managers

and other organization members to develop

a contract or

agreement

to engage in planned change. The contract

spells out future change

activities, the resources

that

will

be committed to the process, and how OD

practitioners and organization members

will be involved. In

many

cases, organizations do not

get beyond this early stage of planned

change because

disagreements

about

the need for change surface,

resource constraints are

encountered, or other methods

for change

appear

more feasible. When OD is

used in nontraditional and

international settings, the entering

and

contracting

process must be sensitive to the

context in which the change is

taking place.

Diagnosing:

In

this stage of planned change, the client

system is carefully studied. Diagnoses

can .focus on

understanding

organizational problems, including their

causes and consequences, or on

identifying the

organization's

positive attributes. The diagnostic

process is one of the most

important activities in OD. It

includes

choosing an appropriate model for understanding the

organization and gathering, analyzing,

and

feeding

back information to managers

and organization members about the

problems or opportunities

that

exist.

Diagnostic

models for analyzing

problems explore three levels of

activities. Organization issues

represent

the

most complex level of analysis and

involve the total system.

Group-level issues are

associated with de-

partment

and group effectiveness.

Individual-level issues involve the

way jobs are

designed.

Gathering,

analyzing, and feeding back

data are the central change

activities in diagnosis. Describes

how

data

can be gathered through interviews,

observations, survey instruments, or

such archival sources as

meeting

minutes and organization charts. It

also explains how data

can be reviewed and

analyzed.

Organization

members, often in collaboration

with an OD practitioner, jointly

discuss the data and

their

implications

for change.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Planning

and Implementing Change:

In

this stage, organization members and

practitioners jointly plan and implement

OD interventions. They

design

interventions to achieve the

organization's vision or goals

and make action plans to implement

them.

There

are several criteria for

designing interventions, including the

organization's readiness for

change, its

current

change capability, its culture and power

distributions, and the change

agent's skills and

abilities.

Depending

on the outcomes of diagnosis, there

are four major types of

interventions in OD:

1.

Human

process interventions at the individual,

group, and total system

levels.

2.

Interventions

that modify an organization's

structure and technology.

3.

Human

resource interventions that

seek to improve member

performance and

wellness.

4.

Strategic

interventions that involve

managing the organization's relationship to

its external

environment

and the internal structure

and process necessary to support a

business strategy.

Implementing

interventions is concerned with

managing the change process. It

includes motivating

change,

creating

a desired future vision of the

organization, developing political support,

managing the transition

toward

the vision, and sustaining momentum

for change.

Evaluating

and Institutionalizing Change:

The

final stage in planned change

involves evaluating the effects of the

intervention and managing

the

institutionalization

of successful change programs.

Feedback to organization members about

the

intervention's

results provides information about

whether the changes should be continued, modified,

or

suspended.

Institutionalizing successful changes

involves reinforcing them through

feedback, rewards,

and

training.

It demonstrates how traditional planned

change activities, such as

entry and contracting,

survey

feedback,

and change planning, can be

combined with contemporary methods, such

as large-group

interventions

and high levels of

participation.

Different

types of Planned Change:

The

general model of planned change describes

how the OD process typically

un-folds in organizations. In

actual

practice, the different phases

are not nearly as orderly as

the model implies. OD practitioners tend

to

modify

or adjust the stages to fit the

needs of the situation. Steps in planned

change may be implemented

in

a variety of ways, depending on the client's

needs and goals, the change

agent's skills and values,

and the

organization's

context. Thus, planned change can vary

enormously from one

situation to another.

To

understand the differences better,

planned change can be contrasted

across situations on three

key

dimensions:

the magnitude of organizational change, the

degree to which the client

system is organized,

and

whether

the setting is domestic or

international.

Magnitude

of Change:

Planned

change efforts can be

characterized as falling along a

continuum ranging from incremental

changes

that

involve fine-tuning the organization to quantum

changes that entail fundamentally altering

how it

operates.

Incremental changes tend to involve

limited dimensions and

levels of the organization, such

as

the

decision-making processes of work

groups. They occur within

the context of the organization's

existing

business

strategy, structure, and culture

and are aimed at improving

the status quo. Quantum changes,

on

the

other hand, are directed at

significantly altering how the organization operates.

They tend to involve

several

organizational dimensions, including

structure, culture, reward systems,

information processes,

and

work

design. They also involve

changing multiple levels of the

organization, from top-level

management

through

departments and work groups

to individual jobs.

Planned

change traditionally has

been applied in situations involving

incremental change. Organizations

in

the

1960s and 1970s were

concerned mainly with fine-tuning

their bureaucratic structures by

resolving

many,

of the social problems that

emerged with increasing size

and complexity. In those

situations, planned

change

involves a relatively bounded set of

problem-solving activities. OD practitioners

are typically

contracted

by managers to help solve

specific problems in particular organizational

systems, such as poor

communication

among members of a work team

or low customer satisfaction

scores in a department store.

Diagnostic

and change activities tend to be limited

to the defined issues, although

additional problems

may

be

uncovered and may need to be

addressed. Similarly, the change process

tends to focus on

those

organizational

systems having specific problems,

and it generally terminates when the

problems are

resolved.

Of course, the change agent

may contract to help solve

additional problems.

In

recent years, OD has been

concerned increasingly with quantum

change. The greater

competitiveness

and

uncertainty of today's environment have

led a growing number of organizations to alter

drastically the

way

in which they operate. In such

situations, planned change is more

complex, extensive, and long

term

than

when applied to incremental change.

Because quantum change involves most

features and levels of

the

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

organization,

it is typically driven from the

top, where corporate strategy

and values are set.

Change agents

help

senior managers create a

vision of a desired future organization

and energize movement in

that

direction.

They also help executives

develop structures for managing the

transition from the present to

the

future

organization and may include, for

example, a variety of overlapping

steering committees

and

redesign

teams. Staff experts also

may redesign many features

of the firm, such as performance

measures,

rewards,

planning processes, work

designs, and information

systems.

Because

of the complexity and extensiveness of

quantum change, OD professionals often

work in teams

comprising

members with different yet

complementary areas of expertise.

The consulting relationship

persists

over relatively long time periods

and includes a great deal of

renegotiation and experimentation

among

consultants and managers.

The boundaries of the change

effort are more uncertain

and diffuse than

in

incremental change, thus making

diagnosis and change seem

more like discovery than

like problem

solving.

It

is important to emphasize that quantum

change may or may not be

developmental in nature.

Organizations

may drastically alter their

strategic direction and way

of operating without significantly

developing

their capacity to solve

problems and to achieve both

high performance and quality

of work life.

For

example, firms may simply change

their marketing mix, dropping or adding

products, services, or

customers;

they may drastically downsize by

cutting out marginal

businesses and laying off

managers and

workers;

or they may tighten managerial

and financial controls and attempt to

squeeze more out of

the

labor

force. On the other hand, organizations

may undertake quantum change

from a developmental

perspective.

They may seek to make

themselves more competitive by developing

their human resources;

by

getting

managers and employees more

involved in problem solving and

innovation; and by

promoting

flexibility

and direct, open communication. That OD

approach to quantum change is particularly

relevant

in

today's rapidly changing and

competitive environment. To succeed in

this setting, major multinational

organizations

(firms such as General Electric, Kimberly-Clark,

ABB, Hewlett-Packard, and Motorola)

are

transforming

themselves from control-oriented

bureaucracies to high-involvement

organizations capable of

changing

and improving themselves

continually.

Degree

of Organization:

Planned

change efforts also can vary

depending on the degree to which the organization or

client system is

organized.

In over organized situations,

such as in highly mechanistic,

bureaucratic organizations,

various

dimensions

such as leadership styles,

job designs, organization structure,

and policies and procedures

are

too

rigid and overly defined

for effective task performance.

Communication between management

and

employees

is typically suppressed, conflicts are

avoided, and employees are

apathetic. In under organized

organizations,

on the other hand, there is

too little constraint or regulation for

effective task performance.

Leadership,

structure, job design, and

policy are poorly defined

and fail to control task

behaviors effective-

ly.

Communication is fragmented, job responsibilities

are ambiguous, and

employees' energies

are

dissipated

because they lack direction.

Underorganized situations are typically

found in such .areas

as

product

development, project management, and

community development, where relationships

among

diverse

groups and participants must be

coordinated around complex, uncertain tasks.

In

over organized situations,

where much of OD practice

has historically taken place, planned

change is

generally

aimed at loosening constraints on

behavior. Changes in leadership,

job design, structure,

and

other

features are designed to liberate

suppressed energy, to increase the

flow of relevant information

between

employees and managers, and

to promote effective conflict resolution.

The typical steps of

planned

change -- entry, diagnosis,

intervention, and evaluation -- are

intended to penetrate a relatively

closed

organization or department and make it

increasingly open to self-diagnosis and

revitalization. The

relationship

between the OD practitioner and the

management team attempts to model this

loosening

process.

The consultant shares leadership of the

change process with

management, encourages open

communications

and confrontation of conflict,

and maintains flexibility in relating to

the organization.

When

applied to organizations facing problems in being

under organized, planned change is aimed

at

increasing

organization by clarifying leadership

rules, structuring communication between,

managers and

employees,

and specifying job and

departmental responsibilities. These

activities require a modification of

the

traditional phases of planned change

and include the following four

steps.

1.

Identification: This

step identifies the relevant people or groups

who need to be involved in the

change

program.

In many under organized situations,

people and departments can be so

disconnected that there

is

ambiguity

about who should be included in the

problem-solving process. For

example, when managers of

different

departments have only

limited interaction with

each other, they may

disagree or be confused

about

which departments should be involved in

developing a new product or

service.

2.

Convention: In this

step the relevant people or departments in the

company are brought together

to

begin

organizing for task performance.

For example, department,

managers might be asked to attend

a

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

series

of organizing meetings to discuss the

division of labor and the

coordination required to introduce

a

new

product.

3.

Organization: Different

organizing mechanisms are created to

structure the newly required interactions

among

people and departments. This might

include creating new leadership

positions, establishing

communication

channels, and specifying appropriate

plans and policies.

4.

Evaluation: In this

final step the outcomes of the

organization step are assessed.

The evaluation might

signal

the need for adjustments in the

organizing process or for further

identification, convention,

and

organization

activities.

In

carrying out these four

steps of planned change in under

organized situations, the relationship

between

the

OD practitioner and the client

system attempts to reinforce the organizing

process. The consultant

develops

a well-defined leadership role, which

might be autocratic during the

early stages of the

change

program.

Similarly, the consulting relationship is clearly

defined and tightly

specified. In effect, the

interaction

between the consultant and the client

system supports the larger

process of bringing order

to

the

situation.

Domestic

vs. International

Settings:

Planned

change efforts traditionally

have been applied in North American

and European settings

but

increasingly

are used outside of those

cultures. Developed in western

societies, the action research

model

reflects

the underlying values and

assumptions of these geographic

settings, including equality,

involvement,

and

short-term time horizons. Under such conditions, the

action research model works quite well.

In other

societies,

however, a very different set of cultural

values and assumptions may

operate and make the

application

of OD problematic. For example, the

cultures of most Asian countries

are more hierarchical

and

status conscious, are less

open to discussing personal issues,

more concerned with saving

"face," and

have

a longer time horizon for results.

Even when the consultant is aware of the

cultural norms and

values

that

permeate the society; those cultural

differences make the traditional action

research steps more

difficult

for

a North American or European consultant to

implement.

The

cultural values that guide OD

practice in the United States,

for example, include a tolerance

for

ambiguity,

equality among people, individuality,

and achievement motives. An OD

process that

encourages

openness

among individuals, high levels of

participation, and actions

that promote increased

effectiveness

are

viewed favorably. The OD practitioner is

also assumed to hold those

values and to model them in the

conduct

of planned change. Most reported cases of

OD involve western-based organizations

using

practitioners

trained in the traditional model and

raised and experienced in

western society.

When

OD is applied outside of the North American or

European context (and sometimes

even within

those

settings), the action research process

must be adapted to fit the cultural

context. For example, the

diagnostic

phase, which is aimed at understanding

the current drivers of organization effectiveness, can

be

modified

in a variety of ways. Diagnosis can

involve many organization members or

include only senior

managers;

be directed from the top,

conducted by an outside consultant, or

performed by internal

consultants;

or involve face-to-face interviews or organization

documents. Each step in the

general model

of

planned change must be carefully mapped

against the cultural context.

Conducting

OD in international settings is highly

stressful on OD practitioners. To be successful,

they

must

develop a keen awareness of their

own cultural biases, be open to seeing a

variety of issues from

another

perspective, be fluent in the values

and assumptions of the host country,

and understand the

economic

and political context of

business there. Most OD practitioners

are not able to meet

all of those

criteria

and adopt a "cultural guide,"

often a member of the organization, to

help navigate the cultural,

operational,

and political nuances of

change in that

society.

Critique

of Planned Change:

Despite

their continued refinement, the models

and practice of planned change

are still in a formative

stage

of

development, and there is considerable

room for improvement. Critics of OD

have pointed out

several

problems

with the way planned change

has been conceptualized and

practiced.

Conceptualization

of Planned Change:

Planned

change has typically been

characterized as involving a series of

activities for carrying out

effective

organization

development. Although current models

outline a general set of

steps to be followed,

considerably

more information is needed to

guide how those steps should

be performed in specific

situations.

In an extensive review and critique of

planned change theory, Porras

and Robertson argued

that

planned

change activities should be guided by information

about (1) the organizational features

that can be

changed,

(2) the intended outcomes from making

those changes, (3) the

causal mechanisms by which

those

outcomes

are achieved, and (4) the

contingencies upon which

successful change depends. In

particular,

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

they

noted that the key to organizational

change is change in the behavior of

each member and that

the

information

available about the causal mechanisms

that produce individual change is

lacking. Overall,

Porras

and Robertson concluded that the

necessary information to guide

change is only partially

available

and

that a good deal more

research and thinking are

needed to fill the

gaps.

A

related area where current

thinking about planned change is

deficient is knowledge about how the

stages

of

planned change differ across

situations. Most models

specify a general set of

steps that are intended

to

be

applicable to most change

efforts. We already know, however,

how change activities can vary

depending

on

such factors as the magnitude of

change, the degree to which the

client system is organized,

and

whether

change is being conducted in a domestic

or an international setting. Considerably

more effort

needs

to be expended identifying situational

factors that may require

modifying the general stages

of

planned

change. That would likely

lead to a rich array of planned

change models, each geared

to a specific

set

of situational conditions. Such contingency thinking

is sorely needed in planned

change.

Planned

change also tends to be

described as a rationally controlled,

orderly process. Critics

have argued

that

although this view may be

comforting, it is seriously misleading.

They point out that planned

change

has

a more chaotic quality,

often involving shifting

goals, discontinuous activities,

surprising events,

and

unexpected

combinations of changes. For example,

managers often initiate

changes without clear plans

that

clarify

their strategies and goals.

As change unfolds, new

stakeholders may emerge and

demand

modifications

reflecting previously unknown or unvoiced needs.

Those emergent conditions

make planned

change

a far more disorderly and

dynamic process than is

customarily portrayed, and conceptions

need to

capture

that reality.

Finally,

the relationship between planned change

and organizational performance and

effectiveness is not

well

understood. OD traditionally has had

problems assessing whether interventions

are producing

observed

results. The complexity of the

change situation, the lack of

sophisticated analyses, and the

long

time

periods for producing

results have contributed to

weak evaluation of OD efforts. Moreover,

managers

have

often accounted for OD

efforts with post hoc

testimonials, reports of possible future

benefits, and

calls

to support OD as the right thing to

do. In the absence of rigorous assessment

and measurement, it is

difficult

to make resource allocation decisions

about change programs and to

know which interventions

are

most

effective in certain situations.

Practice

of Planned Change:

Critics

have suggested several

problems with the way planned

change is carried out. Their

concerns are not

with

the planned change model itself but

with how change takes

place and with the qualifications

and

activities

of OD practitioners.

A

growing number of OD practitioners have

acquired skills in a specific

technique, such as team

building,

total

quality management, large-group

interventions, or gain sharing

and have chosen to

specialize in that

method.

Although such specialization

may be necessary, it can

lead to a certain myopia given the

complex

array

of techniques that make up modern

OD. Some OD practitioners favor

particular techniques and

ignore

other strategies that might

be more appropriate, tending to interpret

organizational problems as

requiring

the favored technique. Thus,

for example, it is not

unusual to see consultants pushing

such

methods

as diversity training, reengineering, organization

learning, or self-managing work teams as

so-

lutions

to most organizational problems.

Effective

change depends on a careful

diagnosis of how the organization is

functioning. Diagnosis

identifies

the underlying causes of organizational

problems, such as poor

product quality and

employee

dissatisfaction.

It requires both time and money,

and some organizations are

not willing to make

the

necessary

investment. Rather, they rely on preconceptions about

what the problem is and hire

consultants

with

skills appropriate to solve that

problem. Managers may think,

for example, that work

design is the

problem,

so they hire an expert in job enrichment to implement

a change program. The

problem may be

caused

by other factors such as

poor reward practices, however,

and job enrichment would

be

inappropriate.

Careful diagnosis can help to

avoid such mistakes.

In

situations requiring complex organizational

changes, planned change is a long-term

process involving

considerable

innovation and learning on site. It

requires a good deal of time

and commitment and a

willingness

to modify and refine changes

as the circumstances require. Some

organizations demand

more

rapid

solutions to their problems and

seek quick fixes from

experts. Unfortunately, some OD

consultants

are

more than willing to provide

quick solutions. They sell prepackaged

programs for organizations

to

adopt.

Those programs appeal to

managers because they typically include

an explicit recipe to be

followed,

standard

training materials, and

clear time and cost

boundaries. The quick fixes

have trouble gaining wide

organizational

support and commitment, however, and they

seldom produce the positive

results that have

been

advertised.

Other

organizations have not

recognized the systemic nature of

change. Too often they

believe that

intervention

into one aspect or subpart

of the organization will be sufficient to

ameliorate the problems,

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

and

are unprepared for the other

changes that may be

necessary to support a particular

intervention. For

example,

at GTE of California, the positive

benefits of an employee involvement program

did not begin to

appear

until after the organization redesigned

its reward system to support the

cross-functional

collaboration

necessary to solve highly complex

problems. Changing any one

part or feature of an

organization

often requires adjustments in the

other parts to maintain an appropriate alignment.

Thus,

although

quick fixes and change

programs that focus on only

one part or aspect of the organization

may

resolve

some specific problems, they

generally do not lead to complex

organizational change or increase

members'

capacity to carry out

change.

Case:

The Dim Lighting Co.

The

Dim Lighting Company is a

subsidiary of a major producer of electrical

products. Each

subsidiary

division

operates as a profit center

and reports to regional, group, and

product vice presidents at

corporate

headquarters.

The Dim Lighting subsidiary

produces electric lamps and

employs about 2,000 workers.

The

general

manager is Jim West, an MBA

from Wharton, who has been

running this subsidiary successfully

for

the

past five years. However,

last year the division

failed to realize its operating

targets, and profit

margins

dropped

by 15 percent. In developing next year's

budget and profit plan, Jim

West feels that he is

under

pressure

to have a good year because

two bad years in a row

might hit his long-term

potential for

advancement.

Mr.

Spinks, Director of R&D

Robert

Spinks, director of R&D, was

hired by West three years

ago, after resigning from a

major

competitor.

Mr. Spinks has received a

number of awards from scientific

societies. The scientists

and

engineers

in his group respect his

technical competence and

have a high level of

morale.

Although

Spinks is recognized as a talented

scientist, other managers feel

that he is often autocratic,

strong-

willed,

and impatient. Spins left

his former company because

management lacked creativity and

innovation

in

R&D.

The

Proposal

Spinks

has submitted a budget request for a

major research project, the micro-miniaturization of

lighting

sources

so as to greatly reduce energy

requirements. He sees this as the Lamp of the Future.

The proposed

budget

requires $250,000 per year

for two years, plus another

$300,000 to begin production. Jim

West

immediately

contacted corporate headquarters, and

although top management

praised the idea, they

were

reluctant

to spend on the proposed project. Spinks

feels the project has a 70

percent chance of success,

and

will

develop a net cash flow of $1 million by

the third year.

The

Budget Meeting

West

called a meeting of his

management group to discuss the

proposed budget. Spinks

presented a well-

reasoned

and high-powered sales pitch

for his project. He suggested

that the energy crunch had

long-term

implications,

and if they failed to move

into new technologies, the

firm would be competitively

obsolete.

Carol

Preston, accountant, presented a

financial analysis of the proposed project,

noting the high risk,

the

uncertain

results, the length of time before it

would contribute to operating profits.

"These scientists are

prima

donnas, who can afford to

wait for long-term results.

Unfortunately, if we don't do something

about

the

bottom line right now, we

may not be here to enjoy

it," she noted.

Bill

Boswell, production manager,

agreed with Preston: "We

need new machinery for

our production line

also,

and that has a very direct

payback."

Pete

Newell, marketing, agreed with

Spinks: "I don't feel we can

put our heads in the sand.

If we don't

keep

up competitively, how will

our salespeople be able to

keep selling obsolete

lighting products?

Besides,

I'm

not sure that Carol's

figures are completely accurate in

measuring the actual return on this

low-energy

project."

A stormy debate followed,

with heated arguments both

for and against the project,

until West

called

the meeting to a halt.

Later,

thinking it over in his

office, West considered the situation.

Going ahead with the

micro-

miniaturization

project was a big gamble.

But if he decided against

it, it was quite possible

that .Spinks

would

resign, which would shatter

the R&D department he had worked so hard to

assemble.

Case

Analysis Form

Name:

____________________________________________

I.

Problems

A.

Macro

1.

____________________________________________________

2.

____________________________________________________

B.

Micro

1.

_____________________________________________________

2.

_____________________________________________________

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

II.

Causes

1.

_____________________________________________________

2.

_____________________________________________________

3.

_____________________________________________________

III.

Systems affected

1.

Structural

____________________________________________

2.

Psychosocial

__________________________________________.

3.

Technical

______________________________________________

4.

Managerial

_____________________________________________

5.

Goals

and values

__________________________________________

IV.

Alternatives

1.

_________________________________________________________

2.

_________________________________________________________

3.

________________________________________________________

V.

Recommendations

1.

_________________________________________________________

2.

__________________________________________________________

3.

__________________________________________________________

Case

Solution: The Dim Lighting Co.

I.

Problems:

A.

Macro

1.

Will

Dim Lighting be

reactive?

2.

Will

Dim Lighting be

proactive?

B.

Micro

1.

Will

Jim West be influenced by thoughts of what a

second year of un-obtained

targets will

do

to

his

career in making this budget

decision?

2.

West

feels threatened every time

Spinks does not receive

his demands or "wish

list."

II.

Causes:

1.

Previous

unprofitable year.

2.

Spinks'

past history of leaving a company

that "lacked creativity and

innovation".

III.

Systems affected:

1.

Structural

the structure is a traditional

functional structure. This may

not encourage the

development

of new products and

ideas.

2.

Psychosocial

other departments feel threatened

by Spinks. Also, Jim West

feels he is

under

pressure

to improve the profit margins

immediately.

3.

Technical

both the production manager

and Spinks want money to

upgrade technical

aspects

of the company.

4.

Managerial

West feels caught

between being innovative and

trying to improve the bottom

line

immediately.

5.

Goals

and values corporate headquarters

does not seem to value risk

taking and moving

into

new

projects. If their rejection of the

lighting proposal is indicative of their

decisions,

the

company

as

a whole may become

entrenched in old technology.

IV.

Alternatives:

1.

Before

making a budget decision, West should

contact corporate offices to see

if

additional

funds

are available for R&D.

Spinks' project would have a

long-term effect on

entire

industry and

possibly

the parent company would contribute to

the R&D project.

2.

If

additional funds are unavailable, the

budget committee needs to make

some

compromises

and

come to a consensus-it should not be an

all-or-nothing proposition.

Funds

should be allocated for

both

R&D and for upgrading essential

equipment.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

3.

West

should also ask the accountant,

Preston, to make a three-tiered analysis

of the project:

(1)

best-case

scenario, (2) worst-case

scenario, and (3) probable

scenario.

4.

West

also needs to resolve his

mixed feelings about the possibility of

Spinks leaving. West

needs

to

approach Spinks, praising

him for what he has

accomplished in the R&D

department

and asking

him

to help spread that high

degree of morale across the

company. West needs to make

Spinks an ally

rather

than a potential

deserter.

V.

Recommendations:

1.

First

try to obtain additional funds

from parent company.

2.

If

additions are not available,

obtain a consensus from the budget

committee. Compromises

will

have

to be made on length of time for R&D

projects, what equipment is needed,

etc.

Table of Contents:

- The Challenge for Organizations:The Growth and Relevance of OD

- OD: A Unique Change Strategy:OD consultants utilize a behavioral science base

- What an “ideal” effective, healthy organization would look like?:

- The Evolution of OD:Laboratory Training, Likert Scale, Scoring and analysis,

- The Evolution of OD:Participative Management, Quality of Work Life, Strategic Change

- The Organization Culture:Adjustment to Cultural Norms, Psychological Contracts

- The Nature of Planned Change:Lewin’s Change Model, Case Example: British Airways

- Action Research Model:Termination of the OD Effort, Phases not Steps

- General Model of Planned Change:Entering and Contracting, Magnitude of Change

- The Organization Development Practitioner:External and Internal Practitioners

- Creating a Climate for Change:The Stabilizer Style, The Analyzer Style

- OD Practitioner Skills and Activities:Consultant’s Abilities, Marginality

- Professional Values:Professional Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, Technical Ineptness

- Entering and Contracting:Clarifying the Organizational Issue, Selecting an OD Practitioner

- Diagnosing Organizations:The Process, The Performance Gap, The Interview Data

- Organization as Open Systems:Equifinality, Diagnosing Organizational Systems

- Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Methods for Collecting Data, Observations

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Sampling, The Analysis of Data

- Designing Interventions:Readiness for Change, Techno-structural Interventions

- Leading and Managing Change:Motivating Change, The Life Cycle of Resistance to Change

- Leading and managing change:Describing the Core Ideology, Commitment Planning

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Measurement

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Research Design

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Group Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Leadership and Authority, Group Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Third-Party Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Building, Team Building Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Management Styles

- Organization Process Approaches:Application Stages, Microcosm Groups

- Restructuring Organizations:Structural Design, Process-Based Structures

- Restructuring Organizations:Downsizing, Application Stages, Reengineering

- Employee Involvement:Parallel Structures, Multiple-level committees

- Employee Involvement:Quality Circles, Total Quality Management

- Work Design:The Engineering Approach, Individual Differences, Vertical Loading

- Performance Management:Goal Setting, Management by Objectives, Criticism of MBO

- Developing and Assisting Members:Career Stages, Career Planning, Job Pathing

- Developing and Assisting Members:Culture and Values, Employee Assistance Programs

- Organization and Environment Relationships:Environmental Dimensions, Administrative Responses

- Organization Transformation:Sharing the Vision, Three kinds of Interventions

- The Behavioral Approach:The Deep Assumptions Approach

- Seven Practices of Successful Organizations:Training, Sharing Information