|

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

# 44

The

Behavioral Approach

This

method of diagnosis emphasizes the

surface level of organization culture--the pattern of

behaviors

that

produce business results. It is

among the more practical

approaches to culture diagnosis because

it

assesses

key work behaviors that

can be observed. The behavioral

approach provides specific

descriptions

about

how tasks are performed

and how relationships are

managed in an organization. For example,

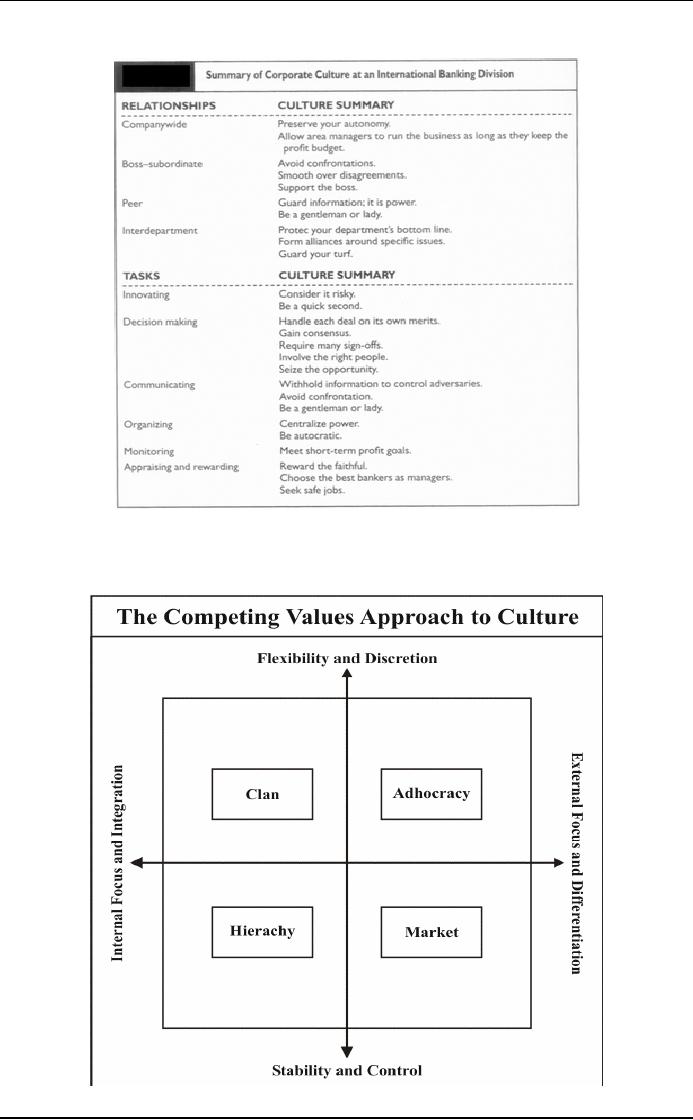

Table

25

summarizes the organization culture of an

international banking division as

perceived by its

managers.

The

data were obtained from a

series of individual and

group interviews asking managers to

describe "the

way

the game is played," as if they were

coaching a new organization member.

Managers were asked to

give

their

impressions in regard to four

key relationships--companywide, boss-subordinate,

peer, and

interdepartmental--and

in terms of six managerial

tasks--innovating, decision making,

communicating,

organizing,

monitoring, and appraising/rewarding.

These perceptions revealed a number of

implicit norms

for

how tasks are performed

and relationships managed at the

division.

Cultural

diagnosis derived from a behavioral

approach can also be used to

assess the cultural risk of trying

to

implement organizational changes needed to

support a new strategy. Significant

cultural risks result when

changes

that are highly important to

implementing a new strategy are

incompatible with the existing

patterns

of behavior. Knowledge of such

risks can help managers

determine whether implementation

plans

should

be changed to manage around the existing culture,

whether the culture should be changed, or

whether

the strategy itself should be modified or

abandoned.

The

Competing Values

Approach

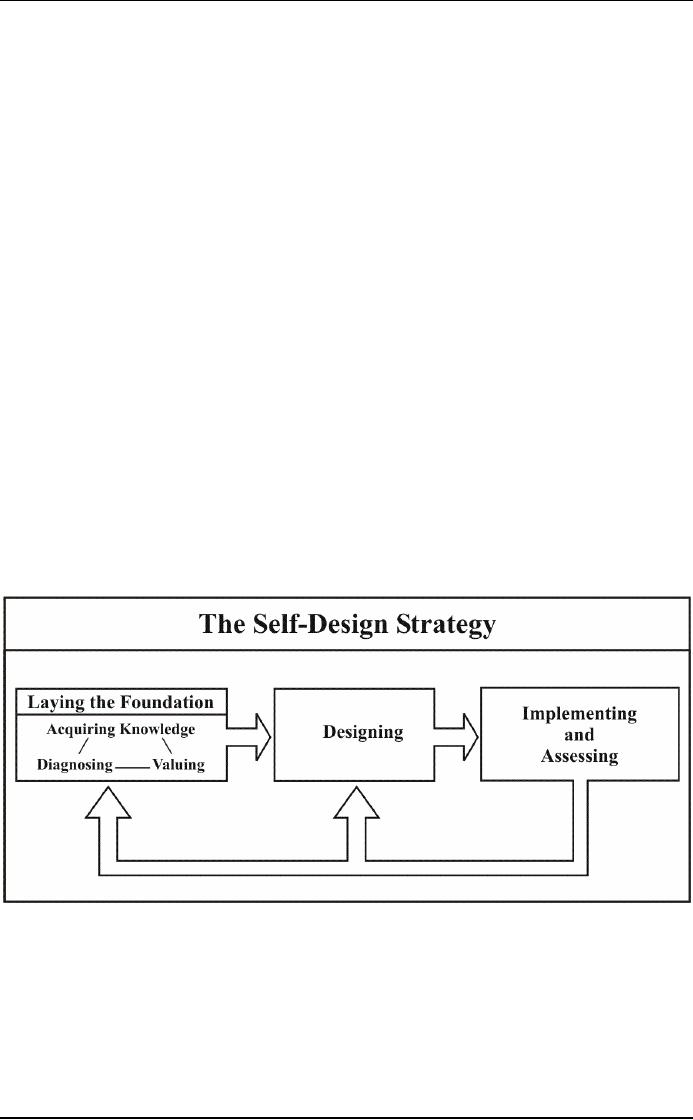

This

perspective assesses an organization's

culture in terms of how it resolves a

set of value dilemmas.

The

approach

suggests that an organization's culture

can be understood in terms of two

important "value pairs";

each

pair consists of contradictory

values placed at opposite ends of a

continuum, as shown in Figure

59.

The

two value pairs are

(1) internal focus and

integration versus external focus

and differentiation and

(2)

flexibility

and discretion versus stability

and control. Organizations continually

struggle to satisfy the

conflicting

demands placed on them by these competing

values. For example, when

faced with the

competing

values of internal versus external

focus, organizations must

choose between attending to the

integration

problems of internal operations or the

competitive issues in the external

environment. Too

much

emphasis on the environment can

result in neglect of internal

efficiencies. Conversely, too

much

attention

to the internal aspects of organizations

can result in missing

important changes in the

competitive

environment.

The

competing values approach commonly

collects diagnostic data about the

competing values with a

survey

designed specifically for

that purpose. It provides measures of

where an organization's existing

values

fall along each of the dimensions.

When taken together, these

data identify an organization's

culture

as

falling into one of the four

quadrants shown in Figure 59:

clan culture, adhocracy culture,

hierarchical

culture,

and market culture. For

example, if an organization's values

are focused on internal

integration

issues

and emphasize innovation and

flexibility, it manifests a clan culture.

On the other hand, a

market

culture

characterizes values that

are externally focused and

emphasize stability and

control.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Table

25

Figure

59

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

The

Deep Assumptions

Approach

This

final diagnostic approach

emphasizes the deepest levels of

organization culture--the

generally

unexamined,

but tacit and shared

assumptions that guide

member behavior and that

often have a powerful

impact

on organization effectiveness. Diagnosing culture from

this perspective typically begins

with the

most

tangible level of awareness and then

works down to the deep

assumptions.

Diagnosing

organization culture at the deep assumptions level

poses at least three

difficult problems

for

collecting

pertinent information. First, culture

reflects shared assumptions

about what is important,

how

things

are done, and how people

should behave in organizations. People

generally take cultural

assumptions

for

granted and rarely speak of

them directly. Rather, the

company's culture is implied in

concrete

behavioral

examples, such as daily routines,

stories, rituals, and language. This

means that considerable

time

and

effort must be spent observing,

sifting through, and asking

people about these cultural outcroppings

to

understand

their deeper significance

for organization members. Second,

some values and beliefs

that

people

espouse have little to do

with the ones they really hold

and follow. People are

reluctant to admit this

discrepancy,

yet somehow the real

assumptions underlying idealized

portrayals of culture must be

discovered.

Third, large, diverse

organizations are likely to

have several subcultures,

including

countercultures

going against the grain of the wider organization culture.

Assumptions may not be

shared

widely

and may differ across

groups in the organization. This means

that focusing on limited

parts of the

organization

or on a few select individuals may

provide a distorted view of the

organization's culture and

subcultures.

All relevant groups in the organization

must be discovered and their

cultural assumptions

sampled.

Only then can practitioners

judge the extent to which assumptions

are shared widely.

OD

practitioners emphasizing the deep

assumptions approach have developed a

number of useful

techniques

for assessing organization culture. One method

involves an iterative interviewing

process

involving

both outsiders and insiders.

Outsiders help members uncover cultural

elements through

joint

exploration.

The outsider enters the organization and

experiences surprises and

puzzles that are

different

from

what was expected. The outsider

shares these observations

with insiders, and the two

parties jointly

explore

their meaning. This process

involves several iterations of experiencing

surprises, checking

for

meaning,

and formulating hypotheses

about the culture. It results in a formal

written description of the

assumptions

underlying an organizational culture.

A

second method for

identifying the organization's basic

assumptions brings together a group of

people for

a

culture workshop--for example, a senior

management team or a cross

section of managers, old and

new

members,

labor leaders, and staff.

The group first brainstorms

a large number of artifacts, such as

behav-

iors,

symbols, language, and

physical space arrangements.

From this list, the values and

norms that would

produce

such artifacts are deduced.

In addition, the values espoused in

formal planning documents

are

listed.

Finally, the group attempts to

identify the assumptions that

would explain the constellation of

values,

norms,

and artifacts. Because they

generally are taken for

granted, they are difficult to

articulate. A great

deal

of process consultation skill is required to

help organization members see the

underlying assumptions.

Application

Stages

There

is considerable debate over whether

changing something as deep-seated as

organization culture is

possible.

Those advocating culture change

generally focus on the more superficial

elements of culture, such

as

norms and artifacts. These

elements are more changeable

than the deeper elements of values

and basic

assumptions.

They offer OD practitioners a more

manageable set of action levers

for changing or-

ganizational

behaviors. Some would argue,

however, that unless the deeper

values and assumptions

are

changed,

organizations have not really

changed the culture.

Those

arguing that implementing culture change

is extremely difficult, if not

impossible, typically focus

on

the

deeper elements of culture (values

and basic assumptions).

Because these deeper

elements represent

assumptions

about organizational life, members do

not question them and have a

difficult time envisioning

anything

else. Moreover, members may

not want to change their cultural

assumptions. The culture provides

a

strong defense against external

uncertainties and threats. It

represents past solutions to difficult

problems.

Members

also may have vested

interests in maintaining the culture. They

may have developed

personal

stakes,

pride, and power in the culture and may

strongly resist attempts to change

it. Finally, cultures

that

provide

firms with a competitive advantage

may be difficult to imitate, thus making

it hard for less

successful

firms to change their cultures to

approximate the more successful

ones.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Given

the problems with cultural change,

most practitioners in this area suggest

that changes in corporate

culture

should be considered only after other,

less difficult and less

costly solutions have been applied

or

ruled

out. Attempts to overcome cultural

risks when strategic changes

are incompatible with culture

might

include

ways to manage around the existing culture. Consider,

for example, a single-product

organization

with

a functional focus and a

history of centralized control

that is considering an ambitious

product-

diversification

strategy. The firm might

manage around its existing culture by

using business teams

to

coordinate

functional specialists around each

new product. Another alternative to

changing culture is to

modify

strategy to bring it more in

line with culture. The single-product

organization just mentioned might

decide

to undertake a less ambitious strategy of

product diversification.

Despite

problems in changing corporate culture,

large-scale cultural change may be

necessary in certain

situations:

if the firm's culture does not fit a

changing environment; if the industry is

extremely competitive

and

changes rapidly; if the company is

mediocre or worse; if the firm is

about to become a very

large

company;

or if the company is smaller and

growing rapidly. Organizations facing

these conditions need

to

change

their cultures to adapt to the

situation or to operate at higher levels

of effectiveness. They may

have

to

supplement attempts at cultural change

with other approaches, such

as managing around the existing

culture

and modifying

strategy.

Although

knowledge about changing corporate culture is in a

formative stage, the following

practical advice

can

serve as guidelines for cultural

change:

1.

Formulate a clear strategic

vision. Effective

cultural change should start from a

clear vision of the

firm's

new strategy and of the

shared values and behaviors

needed to make it work. This

vision provides

the

purpose and direction for

cultural change. It serves as a yardstick

for defining the firm's existing

culture

and

for deciding whether proposed changes

are consistent with core

values of the organization. A

useful

approach

to providing clear strategic

vision is development of a statement of corporate

purpose, listing in

straightforward

terms the firm's core values.

For example, Johnson &

Johnson calls its guiding

principles

"Our

Credo." It describes several

basic values that guide the

firm, including, "We believe

our first

responsibility

is to the doctors, nurses and

patients, to mothers and all

others who use our products

and

services";

"Our suppliers and

distributors must have an

opportunity to make a fair

profit"; "We must

respect

[employees'] dignity and

recognize their merit"; and

"We must maintain in good

order the property

we

are privileged to use,

protecting the environment and natural

resources."

2.

Display top-management commitment.

Cultural

change must be managed from

the top of the

organization.

Senior managers and

administrators have to be strongly committed to the

new values and

need

to create constant pressures

for change. They must

have the staying power to see the

changes

through.

For example, Jack Welch,

CEO at General Electric, has

enthusiastically pushed a policy of

cost

cutting,

improved productivity, customer

focus, and bureaucracy busting

for more than ten years to

every

plant,

division, group, and sector in

his organization. His efforts

were rewarded with a Fortune

cover story

lauding

his organization for creating

more than $52 billion in

shareholder value during his

tenure.

3.

Model culture change at the

highest levels. Senior

executives must communicate the

new culture

through

their own actions. Their

behaviors need to symbolize the kinds of

values and behaviors

being

sought.

In the few publicized cases of successful culture

change, corporate leaders have

shown an almost

missionary

zeal for the new values;

their actions have

symbolized the values forcefully.

For example, Jim

Treybig,

CEO of Tandem, the computer manufacturer,

decided not to fire an

employee whose

performance

had slipped until he could investigate

the reason for the employee's

poor performance. It

turned

out that the employee was

having family problems, and therefore

Treybig gave him another

chance.

To

the people at Tandem, the story

symbolized the importance of consideration in leading

people.

4.

Modify the organization to support

organizational change. Cultural

change generally

requires

supporting

modifications in organizational structure,

human resources systems,

information and

control

systems,

and management styles. These

organizational features can help to

orient people's behaviors to

the

new

culture. They can make people aware of

the behaviors required to get things done in the

new culture

and

can encourage performance of

those behaviors. For

example, Phil Condit and

Harry Stonecipher of

Boeing

realized that more than

culture change in the commercial aircraft

division was necessary to

turn

around

the organization's poor performance in

1997 and 1998. To alter the

"warm and fuzzy" culture

of

the

division radically, they initiated

workforce reductions, fired

key executives, made changes

in the

production

standards, and initiated continuous

improvement processes in production.

These changes rein-

forced

and symbolized the importance of financial

performance, accountability, and global

leadership in the

industry.

5.

Select and socialize newcomers and

terminate deviants. One of the

most effective methods

for

changing

corporate culture is to change organizational

membership. People can be

selected and terminated

in

terms of their fit with the

new culture. This is especially important

in key leadership positions,

where

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

people's

actions can significantly promote or

hinder new values and

behaviors. For example,

Gould, in

trying

to change from an auto parts

and battery company to a leader in

electronics, replaced about

two-

thirds

of its senior executives

with people more in tune with the

new strategy and culture.

Jan Carlzon of

Scandinavian

Airlines (SAS) replaced

thirteen out of fifteen top

executives in his turnaround of the

airline.

Another

approach is to socialize newly hired

people into the new culture. People

are most open to

organizational

influences during the entry

stage, when they can be

effectively indoctrinated into the

culture.

For

example, companies with strong

cultures like Samsung,

Procter & Gamble, and 3M attach

great

importance

to socializing new members

into the company's

values.

6.

Develop ethical and legal sensitivity.

Cultural

change can raise significant

tensions between

organization

and individual interests, resulting in

ethical and legal problems

for practitioners. This is

particularly

pertinent when organizations

are trying to implement cultural values

promoting employee

integrity,

control, equitable treatment, and job

security--values often included in cultural change

efforts.

Statements

about such values provide

employees with certain

expectations about their rights and

about

how

they will be treated in the organization. If the

organization does not follow

through with

behaviors

and

procedures supporting and

protecting these implied

rights, it may breach

ethical principles and, in

some

cases, legal employment contracts.

Recommendations for reducing the

chances of such ethical

and

legal

problems include setting realistic

values for culture change

and not promising what the

organization

cannot

deliver; encouraging input from

throughout the organization in setting cultural

values; providing

mechanisms

for member dissent and

diversity, such as internal review

procedures; and educating

managers

about

the legal and ethical

pitfalls inherent in cultural change

and helping them develop guidelines

for

resolving

such issues.

Self-Designing

Organizations

A

growing number of researchers and

practitioners have called for

self-designing organizations that

have

the

built-in capacity to transform themselves

to achieve high performance in

today's competitive and

changing

environment. Mohrman and

Cummings have developed a self-design

change strategy that

involves

an ongoing series of designing

and implementing activities carried

out by managers and

employees

at

all levels of the firm. The

approach helps members

translate corporate values and

general prescriptions

for

change into specific

structures, processes, and

behaviors suited to their

situations. It enables them to

tailor

changes to fit the organization and

helps them continually to adjust the

organization to changing

conditions.

The

Demands of Transformational

Change

Mohrman

and Cummings developed the self-design

strategy in response to a number of

demands facing

organizations

engaged in transformational change. These

demands strongly suggest the need

for self-design,

in

contrast to more traditional

approaches to organization change that

emphasize ready-made

programs

and

quick fixes. Although

organizations prefer the control and

certainty inherent in programmed

change,

the

five requirements for organizational

transformation reviewed below

argue against this

strategy:

1.

Transformational change generally

involves altering most features of the organization

and achieving a

fit

among them and with the firm's

strategy. This suggests the need

for a systemic change

process that

accounts

for these multiple features

and relationships.

2.

Transformational change generally

occurs in situations experiencing

heavy change and uncertainty.

This

means

that changing is never

totally finished, as new structures

and processes will

continually have to be

modified

to fit changing conditions. Thus, the

change process needs to be

dynamic and iterative,

with

organizations

continually changing

themselves.

3.

Current knowledge about transforming

organizations provides only general

prescriptions for

change.

Organizations

need to learn how to

translate that information

into specific structures,

processes, and

behaviors

appropriate to their situations. This

generally requires considerable on-site

innovation and

learning

as members learn by doing--trying

out new structures and

behaviors, assessing their

effectiveness,

and

modifying them if necessary.

Transformational change needs to

facilitate this organizational learning.

4.

Transformational

change invariably affects

many organization stakeholders, including

owners,

managers,

employees, and customers.

These different stakeholders

are likely to have different

goals and

interests

related to the change process.

Unless the differences are

revealed and reconciled,

enthusiastic

support

for change may be difficult

to achieve. Consequently, the change

process must attend to

the

interests

of multiple stakeholders.

5.

Transformational change needs to

occur at multiple levels of the

organization if new strategies are

to

result

in changed behaviors throughout the

firm. Top executives must

formulate a corporate strategy

and

clarify

a vision of what the organization needs to

look like to support it.

Middle and lower levels of

the

organization

need to put those broad

parameters into operation by

creating structures, procedures,

and

behaviors

to implement the strategy.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Application

Stages

The

self-design strategy accounts

for these demands of organization

transformation. It focuses on all

features

of the organization (for example,

structure, human resources

practices, and technology)

and

designs

them to support the business strategy

mutually. It is a dynamic and an

iterative process aimed

at

providing

organizations with the built-in

capacity to change and

redesign themselves continually as

the

circumstances

demand. The approach

promotes organizational learning among

multiple stakeholders- at

all

levels

of the firm, providing them with the

knowledge and skills needed to transform

the organization and

continually

to improve it.

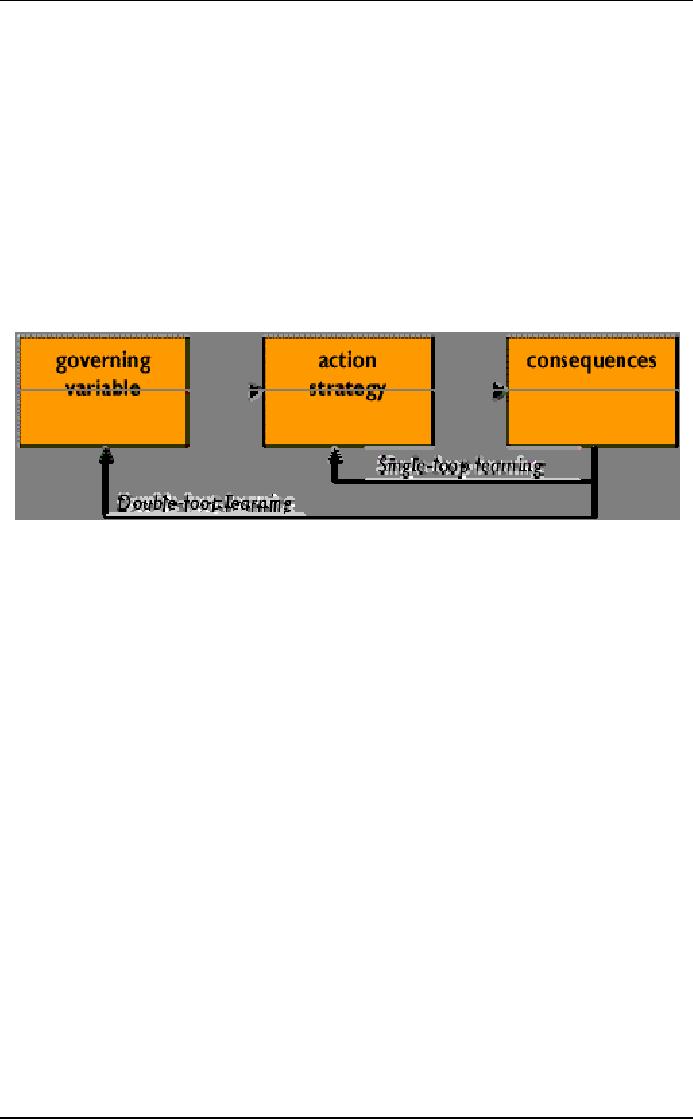

Figure

60 outlines the self-design approach.

Although the process is described in

three stages, in

practice

the

stages merge and interact

iteratively over time. Each

stage is described below:

Figure

60. The Self-Design

Strategy

1.

Laying the foundation. This

initial stage provides organization

members with the basic knowledge

and

information

needed to get started with

organization transformation. It involves three kinds of

activities.

The

first is acquiring knowledge about how

organizations function, about organizing principles

for achiev-

ing

high performance, and about the

self-design process. This information is

generally gained

through

reading

relevant material, attending in-house

workshops, and visiting

other organizations that

successfully

have

transformed themselves. This learning typically

starts with senior

executives or with those

managing

the

transformation process and

cascades to lower organizational levels

if a decision is made to proceed

with

self-design.

The second activity in laying the

foundation involves valuing--determining

the corporate

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

values

that will guide the

transformation process. These

values represent those

performance outcomes

and

organizational

conditions that will be

needed to implement the corporate strategy. They

are typically written

in

a values statement that is

discussed and negotiated among

multiple stakeholders at all

levels of the

organization.

The third activity is

diagnosing the current organization to determine what

needs to be

changed

to enact the corporate strategy and

values. Organization members generally

assess the different

features

of the organization, including its

performance. They look for incongruities

between its

functioning

and

its valued performances and

conditions. In the case of an entirely

new organization, members

diagnose

constraints

and contingencies in the situation

that need to be taken into

account in designing the

organization.

2.

Designing. In this

second stage of self-design, organization

designs and innovations are

generated to

support

corporate strategy and values.

Only the broad parameters of a new

organization are specified; the

details

are left to be tailored to the

levels and groupings within the

organization. Referred to as

minimum

specification

design, this process recognizes

that designs need to be

refined and modified as they

are

implemented

throughout the firm.

3.

Implementing and assessing. This

last stage involves implementing the

designed organization

changes.

It includes an ongoing cycle of action

research: changing structures

and behaviors,

assessing

progress,

and making necessary modifications.

Information about how well

implementation is progressing

and

how well the new organizational

design is working is collected

and used to clarify design

and

implementation

issues and to make necessary

adjustments. This learning process

continues not only

during

implementation

but indefinitely as members periodically

assess and improve the

design and alter it to

fit

changing

conditions. The feedback loops shown in

Figure 20.3 suggest that the implementing

and assessing

activities

may lead back to affect

subsequent designing, diagnosing,

valuing, and acquiring knowledge

activities.

This iterative sequence of activities

provides organizations with the capacity

to transform and

improve

themselves continually.

The

self-design strategy is applicable to

existing organizations needing to transform

themselves, as well as

to

new organizations just starting

out. It is also applicable to

changing the total organization or

subunits.

The

way self-design is managed

and unfolds can also

differ. In some cases, it

follows the existing

organization

structure, starting with the senior

executive team and cascading

downward across orga-

nizational

levels. In other cases, the

process is managed by special

design teams that are

sanctioned to set

broad

parameters for valuing and

designing for the rest of the

organization. The outputs of these

teams

then

are implemented across departments

and work units, with

considerable local refinement

and

modification.

The

Learning Organization

Organization

Learning interventions address how

organizations can be designed to

promote effective

learning

processes and how those

learning processes themselves can be

improved.

The

learning organization builds on a number of ideas. It

has its roots in OD and uses

the ideas and

philosophies

of action research, systems approach,

organizational culture, continuous problem-solving,

self-

managed

work teams, collaboration,

participative leadership, and

interpersonal relations. The

learning

organization

is a system-wide change program that

emphasizes the reduction of organizational

layers and

the

involvement of every body in the

organization in continuous self-directing learning that

will lead toward

positive

change and growth in the

individual, team, and

organization.

According

to Peter Senge, "Leaders in learning

organizations are responsible

for building

organizations

where

individuals continually expand

their capabilities to shape

their future. Leaders are

responsible for

fostering

learning and are themselves

learners." Learning in organizations

means the continuous testing of

experience

and the transformation of that

experience into knowledge accessible to

the whole organization

and

relevant to its core

purpose.

Learning

organizations emphasize creating

"knowledge for action" and

not "knowledge for its

own sake."

They

focus on acquiring knowledge, sharing it

across the organization, and using it to

achieve

organizational

goals. Participants must liberate

themselves from such mental

traps as blaming the

competition,

the economy, or other factors beyond

their control. Learning organization

realize that they are

part

of a larger system over

which they have little or no

control. Instead of complaining, they seek

out

opportunities

and "ride the wave."

Core

Values

A

strong set of core values is

normally present in learning

organizations:

·

Value

different kinds of knowledge and learning

styles.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

·

Encourage

communication between people with

different perspectives and

ideas.

·

Develop

creative thinking.

·

Remain

nonjudgmental of others and their

ideas.

·

Break

down traditional barriers in the

organization.

·

Develop

leadership throughout organization. Everyone is a

leader.

·

Reduce

distinctions between organization members.

(Management vs. non-management,

line vs.

staff,

doers vs. thinkers, professional

vs. nonprofessional, & so on.)

·

Believe

that every member of the organization

has untapped human

potential.

Becoming

a learning organization increases the size of the

organization's "brain." The

employees

throughout

the organization participate in all thinking

activities. The boundaries

between the parts of the

organization

are broken down.

Characteristics

of a Learning Organization

Four

characteristics define a learning organization:

1.

Constant

Readiness: The

organization exists in constant readiness

for change. By staying in

tune

with

its environment, the organization is

ready to take advantage of

new opportunities.

2.

Continuous

Planning: Instead of a

few top executives

formulating fixed plans, the

learning

organization

creates flexible plans that

are fully known and

accepted by the entire organization.

The

plans are constantly reexamined by

those involved with their

implementation not just

top

management.

The old adage that

"the top thinks and the

bottom acts" has given way

to the need

for

"integrated thinking and

acting at all levels."

3.

Improvised

Implementation. The

learning organization improvises. Instead of

rigidly

implementing

plans, it encourages experimentation.

Coordination and collaboration of

everyone

involved

is required in the implementation. Successes are

identified and institutionalized

within the

organization.

4.

Action

Learning.

Change is reevaluated continually

and not just at annual

planning sessions.

Instead

the learning organization is constantly taking action, reflecting,

and making adjustments.

In

short, learning organizations do not wait

for problems to arise. They

are constantly undergoing a

reexamination

that questions and tests

assumptions.

Organization

Learning Processes

These

processes consist of four interrelated

activities:

1.

Discovery: Learning

starts with discovery when

errors or gaps between

desired and actual

conditions are

detected.

For example, sales managers

may discover that sales

are falling below projected

levels and set

out

to

solve the problem.

2.

Invention is

aimed at devising solutions to close the

gap between desired and

current conditions, and

includes

diagnosing the causes of the gap

and creating appropriate solutions to

reduce it.

The

sales

managers

may learn that poor

advertising is contributing to the sales

problem and may devise a

new sales

campaign

to improve sales.

3.

Production processes

involve implementing solutions. For

instance, the new advertising program

would

be

implemented.

4.

Generalization includes

drawing conclusions about the effects of the

solutions, if successful, and

extending

that knowledge, to other relevant

situations. The managers

might use variations of it with

other

product

lines. Thus, these four

learning processes enable members to

generate the knowledge necessary

to

change

and improve the organization.

Levels

of Learning

Inferring

from the learning processes, we can

identify two levels of

learning.

The

lowest level is called single-loop learning or

adaptive learning and is focused on

learning how to

improve

the status quo. This is the most

prevalent form of learning in organizations

and enables members

to

reduce errors or gaps

between desired and existing conditions.

It can produce incremental change

in

how

organizations function. The

sales managers described

above engaged in single-loop learning when

they

looked

for ways to reduce the difference

between current and desired

levels of sales.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Single-loop

learning is like a thermostat that

learns when it is too hot or

too cold and turns the heat on

or

off.

The thermostat can perform

this task because it can

receive information (the temperature of

the room)

and

take corrective action.

Double-loop

learning or generative learning is aimed at

changing the status quo. It operates at a

more

abstract

level than does single-loop learning

because members learn how to

change the existing

assumptions

and conditions within which

single-loop learning operates. This level of learning

can lead to

transformational

change, where the status quo

itself is radically altered.

For example, the sales

managers

may

learn that sales projections

are based on faulty

assumptions and models about

future market

conditions.

This knowledge may result in an

entirely new conception of future

markets with corresponding

changes

in sales projections and product

development plans. It may lead the

managers to drop some

products

that had previously appeared promising,

develop new ones that were

not considered before,

and

alter

advertising and promotional campaigns to

fit the new conditions.

Figure

61

In

Single-loop learning the emphasis is on "techniques

and making techniques more

efficient".

Double-loop

learning is more creative and reflexive.

Reflection here is more fundamental: the

basic

assumptions

behind ideas or policies are

confronted. Hypotheses are

publicly tested.

Table of Contents:

- The Challenge for Organizations:The Growth and Relevance of OD

- OD: A Unique Change Strategy:OD consultants utilize a behavioral science base

- What an “ideal” effective, healthy organization would look like?:

- The Evolution of OD:Laboratory Training, Likert Scale, Scoring and analysis,

- The Evolution of OD:Participative Management, Quality of Work Life, Strategic Change

- The Organization Culture:Adjustment to Cultural Norms, Psychological Contracts

- The Nature of Planned Change:Lewin’s Change Model, Case Example: British Airways

- Action Research Model:Termination of the OD Effort, Phases not Steps

- General Model of Planned Change:Entering and Contracting, Magnitude of Change

- The Organization Development Practitioner:External and Internal Practitioners

- Creating a Climate for Change:The Stabilizer Style, The Analyzer Style

- OD Practitioner Skills and Activities:Consultant’s Abilities, Marginality

- Professional Values:Professional Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, Technical Ineptness

- Entering and Contracting:Clarifying the Organizational Issue, Selecting an OD Practitioner

- Diagnosing Organizations:The Process, The Performance Gap, The Interview Data

- Organization as Open Systems:Equifinality, Diagnosing Organizational Systems

- Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Methods for Collecting Data, Observations

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Sampling, The Analysis of Data

- Designing Interventions:Readiness for Change, Techno-structural Interventions

- Leading and Managing Change:Motivating Change, The Life Cycle of Resistance to Change

- Leading and managing change:Describing the Core Ideology, Commitment Planning

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Measurement

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Research Design

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Group Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Leadership and Authority, Group Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Third-Party Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Building, Team Building Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Management Styles

- Organization Process Approaches:Application Stages, Microcosm Groups

- Restructuring Organizations:Structural Design, Process-Based Structures

- Restructuring Organizations:Downsizing, Application Stages, Reengineering

- Employee Involvement:Parallel Structures, Multiple-level committees

- Employee Involvement:Quality Circles, Total Quality Management

- Work Design:The Engineering Approach, Individual Differences, Vertical Loading

- Performance Management:Goal Setting, Management by Objectives, Criticism of MBO

- Developing and Assisting Members:Career Stages, Career Planning, Job Pathing

- Developing and Assisting Members:Culture and Values, Employee Assistance Programs

- Organization and Environment Relationships:Environmental Dimensions, Administrative Responses

- Organization Transformation:Sharing the Vision, Three kinds of Interventions

- The Behavioral Approach:The Deep Assumptions Approach

- Seven Practices of Successful Organizations:Training, Sharing Information