|

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

# 42

Organization

and Environment Relationships

Organizations

are open systems and must

relate to their environments. They must

acquire the resources

and

information needed to function; they

must deliver products or

services that are valued by

customers.

An

organization's strategy--how it acquires

resources and delivers

outputs--is shaped by particular

aspects,

and

features of the environment.

Thus,

organizations can devise a number of

responses for managing

environmental interfaces,

from

internal

administrative responses, such as

creating special units to scan the

environment, to external

collective

responses, such as forming

strategic alliances with

other organizations.

Organization

and Environment Framework

This

section provides a framework for understanding

how environments affect organizations

and, in turn,

how

organizations can affect environments.

The framework is based on the

concept that organizations

and

their

subunits are open systems existing in

environmental contexts. Environments

can be described in

two

ways.

First, there are different

types of environments that consist of

specific components or forces.

To

survive

and grow, organizations must

understand these different environments,

select appropriate parts to

respond

to, and develop effective relationships

with them. A manufacturing firm,

for example, must

understand

raw materials markets, labor

markets, customer segments,

and production technology

alternatives.

It then must select from a

range of raw material

suppliers, applicants for

employment,

customer

demographics, and production

technologies to achieve desired

outcomes effectively.

Organizations

are thus dependent on their

environments. They need to manage

external constraints and

contingencies

and take advantage of external

opportunities. They also need to

influence the environment in

favorable

directions through such methods as

political lobbying, advertising,

and public relations.

Second,

several useful dimensions

capture the nature of organizational environments.

Some environments

are

rapidly changing and

complex, and so require different

organizational responses than do

environments

that

are stable and simple.

For example, chewing gum

manufacturers face a stable

market and use

well-un-

derstood

production technologies. Their

strategy and organization design

issues are radically

different from

those

of software developers who

face product life cycles

measured in months instead of years,

where labor

skills

are rare and hard to find,

and where demand can

change drastically

overnight.

In

this section, first we describe

different types of environments that

can affect organizations. Then

we

identify

environmental dimensions that influence

organizational responses to external forces.

Finally, we

review

the different ways that

organizations can respond to

their environments. This material

provides an

introductory

context for describing

interventions that concern organization

and environment

relationships:

integrated

strategic change, trans-organizational development,

and mergers and

acquisitions.

Environmental

Types

Organizational

environments are everything beyond the boundaries of

organizations that can directly

or

indirectly

affect performance and outcomes.

That includes external agents

that directly affect the

organization,

such as suppliers, customers,

regulators, and competitors, as well as

indirect influences in the

wider

cultural, political, and economic

context. These two classes of

environments are called the

task

environment

and the general environment,

respectively. We will also

describe the enacted

environment,

which

reflects members' perceptions of the

general and task

environments.

The

general environment consists of

all external forces that can

influence an organization. It can be

categorized

into technological, legal and regulatory,

political, economic, social,

and ecological

components.

Each

of these forces can affect the

organization in both direct and indirect

ways. For example,

economic

recessions

can directly impact demand

for a company's product. The

general environment also can

affect

organizations

indirectly by virtue of the linkages

between external agents. For

example, an organization may

have

trouble obtaining raw

materials from a supplier because the

supplier is embroiled in a labor

dispute

with

a national union, a lawsuit

with a government regulator, or a boycott by a

consumer group. Thus,

components

of the general environment can affect the

organization without having any direct

connection

to

it.

The

task environment consists of the

specific individuals and

organizations that interact directly

with the

organization

and can affect goal

achievement: customers, suppliers,

competitors, producers of

substitute

products

or services, labor unions, financial

institutions, and so on.

These direct relationships are the

medium

through which organizations

and environments mutually influence one

another. Customers,

for

example,

can demand changes in the

organization's products, and the

organization can try to influence

customers'

tastes and desires through

advertising.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

The

enacted environment consists of the

organization's perception and

representation of its general

and

task

environments. Environments must be

perceived before they can influence

decisions about how to

respond

to them. Organization members must

actively observe, register, and

make sense of the

envi-

ronment

before it can affect their decisions

about what actions to take. Thus,

only the enacted

environment

can

affect which organizational responses are

chosen. The general and

task environments, however, can

influence

whether those responses are

successful or ineffective. For

example, members may

perceive cus-

tomers

as relatively satisfied with their

products and may decide to

make only token efforts at

developing

new

products. If those perceptions

are wrong and customers

are dissatisfied with the

products, the meager

product

development efforts can have

disastrous organizational consequences. As a

result, an organization's

enacted

environment should accurately reflect its

general and task environments if

members' decisions

and

actions

are to be effective.

Environmental

Dimensions

Environments

can also be characterized along

dimensions that describe the

organization's context

and

influence

its responses. One perspective

views environments as information flows

and suggests that

organizations

need to process information to

discover how to relate to

their environments. The

key

dimension

of the environment affecting information

processing is information uncertainty, or the

degree to

which

environmental information is ambiguous.

Organizations seek to remove uncertainty

from the

environment

so that they know best how

to transact with it. For

example, organizations may

try to discern

customer

needs through focus groups

and surveys and attempt to

understand competitor strategies

through

press

releases, sales force behaviors,

and knowledge of key personnel.

The greater the uncertainty, the

more

information

processing is required to learn about the

environment. This is particularly evident

when

environments

are complex and rapidly

changing. These kinds of environments

pose difficult

information

processing

problems for organizations.

For example, global competition,

technological change, and

financial

markets have created highly

uncertain and complex environments for

many multinational firms

and

have severely strained their

information processing

capacity.

Another

perspective views environments as

consisting of resources for

which organizations compete.

The

key

environmental dimension is resource

dependence, or the degree to which an

organization relies on

other

organizations for resources.

Organizations seek to manage critical

sources of resource

dependence

while

remaining as autonomous as possible. For

example, firms may contract with

several suppliers of the

same

raw material so that they

are not overly dependent on

one vendor. Resource

dependence is extremely

high

for an organization when other

organizations control critical resources

that cannot be obtained easily

elsewhere.

Resource criticality and

availability determine the extent to

which an organization is dependent

on

the environment and must

respond to its demands. An

example is the tight labor

market for

information

systems experts experienced by

many firms in the late

1990s.

These

two environmental dimensions--information

uncertainty and resource dependence--can

be

combined

to show the degree to which

organizations are constrained by

their environments and

consequently

must be responsive to their

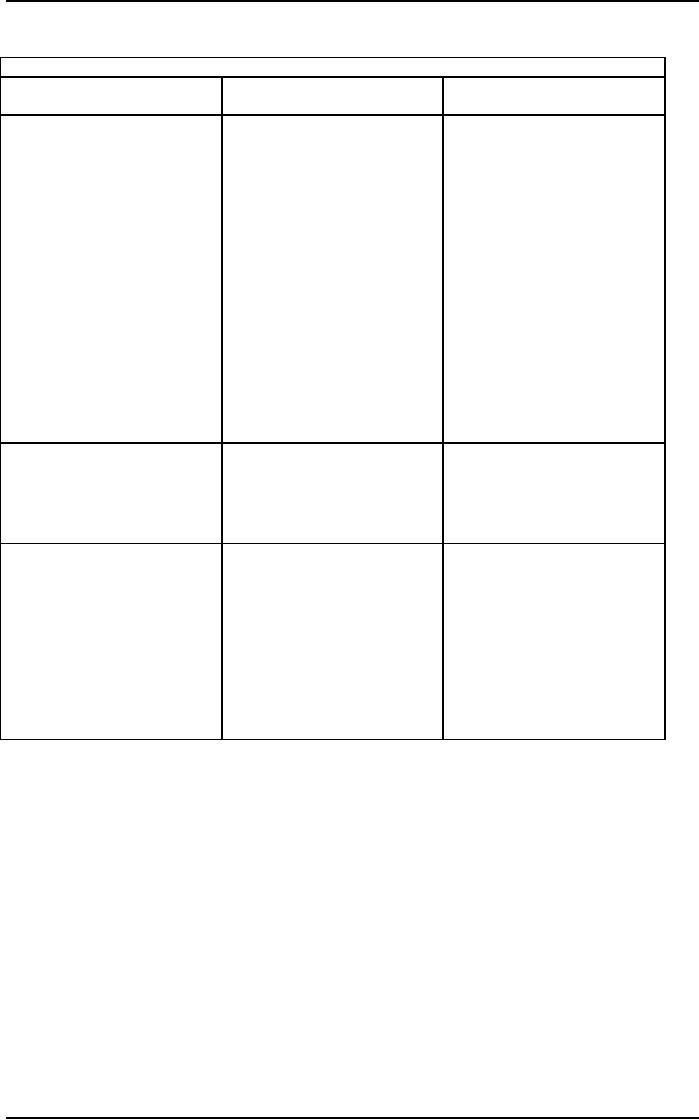

demands. As shown in Figure 58,

organizations have the

most

freedom

from external forces when

information uncertainty and resource

dependence are both low.

In

such

situations, organizations do not

need to respond to their environments

and can behave

relatively

independently

of them. U.S. automotive

manufacturers faced these

conditions in the 1950s and

operated

with

relatively little external constraint or threat. Organizations

are more constrained and

must be more

responsive

to external demands as information uncertainty

and resource dependence

increase. They must

perceive

the environment accurately and

respond to it appropriately. Organizations

such as financial

institutions,

high-technology firms, and health-care

facilities are facing unprecedented

amounts of

environmental

uncertainty and resource dependence.

Their existence depends on recognizing

external

challenges

and responding quickly and appropriately

to them.

Organizational

Responses

Organizations

must have the capacity to

monitor and make sense of

their environments if they are to

respond

appropriately. They must

identify and attend to those

environmental factors and

features that are

highly

related to goal achievement

and performance. Moreover, they

must have the

internal

capacity

to develop effective responses. Organizations employ a number of

methods to influence and

respond

to their environments, to buffer their

technology from external disruptions, and to

link themselves

to

sources of information and

resources. These responses

are generally designed by

senior executives

responsible

for setting corporate strategy

and managing external relationships.

Three classes of responses

are

described below: administrative, competitive, and

collective.

Administrative

Responses

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

The

most common organizational responses to the

environment are administrative, including

the formation

or

clarification of the organization's

mission; the development of objectives,

policies, and

budgets;

or the creation of scanning units. These

responses can be either proactive or

reactive and are

aimed

at defining the organization's purpose

and key tasks in relationship to

particular environments. As

discussed

earlier, an organization's mission

describes its long-term

purpose, including the products or

services

to be offered and the markets to be

served. An effective mission clearly

differentiates the

organization

from others in its

competitive environment. For

example, 3M's core purpose

is to solve

unsolved

problems innovatively. 3M is

distinguished from its competitors by

its attention to unsolved

problems

and its core competence of

innovation. Similarly, an organization's

objectives, policies,

and

budgets

signal which parts of the environment

are important. They allocate

and direct resources to

particular

environmental relationships. Intel's

new product development objectives

and allocation of more

than

20 percent of revenues to research

and development signal the importance of

its linkage to the tech-

nological

environment. Finally, organizations

may create scanning units,

such as market research

and

regulatory

relations departments, to respond administratively to

the environment. These units

scan

particular

parts or aspects of the environment,

interpret relevant information, and

communicate it to

decision

makers who develop appropriate responses.

Scanning units generally include

specialists with

expertise

in a particular segment of the environment.

For example, market

researchers provide

information

to

marketing executives about customer

tastes and preferences. Such

information guides choices

about

product

development, pricing, and

advertising.

Figure

58

Environmental

Dimension and organizational

Transaction

RESOURCE

DEPENDENCE

Low

High

I

N

F

O

Moderate

Constraint

Minimal

environmental

R

and

responsiveness to

Constraint

and need to

M

Low

Environment

Be

responsiveness to

A

Environment

T

I

O

N

U

N

Maximal

C

High

Moderate

environmental

E

Constraint

and

Constraint

and

R

responsiveness

to

need

to Be

T

Environment

responsiveness

to

A

Environment

I

N

I

T

Y

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Competitive

Responses

Competitive

responses to the environment typically

are associated with

for-profit firms but can

also apply

to

nonprofit and governmental organizations.

Such actions seek to enhance

the organization's performance

by

establishing a competitive advantage

over its rivals. To sustain

competitive advantage,

organizations

must

achieve an external position vis-�-vis

their competitors or perform internally

in ways that are

unique,

valuable,

and difficult to imitate.

Uniqueness. An organization

first must identify the

bundle of resources and

processes that make

it

distinct

from other firms. These can

include financial resources, such as

access to low-cost capital;

reputational

resources, such as brand image or a

history of product quality; technological

resources, such as

patents

or a strong research and development department;

and human resources, such as

excellent labor-

management

relationships or scarce and valuable

skill sets. Based on this list, the

organization then

determines

how the resources apply to key

organizational processes--regular patterns of

organizational

activity

that involve a sequence of

tasks performed by individuals. For

example, a software development

process

combines computer resources, software

programs, typing skills, knowledge of

computer languages,

and

customer requirements. Other

organizational processes include new

product development, strategic

planning,

appraising member performance, making

sales calls, fulfilling

customer orders, and the

like.

Processes

and capabilities that are

unique to the organization are called

distinctive competencies

and

represent

the cornerstone of competitive

advantage.

Value.

Organizations achieve competitive

advantage when their resources

and processes deliver

outputs

that

either warrant a higher-than-average price or

are exceptionally low in cost.

Both advantages are

valuable

according to a performance/ price

criterion. Products and

services with highly

desirable features

or

capabilities, although expensive,

are valuable because of

their ability to satisfy

customer demands for

high

quality or some other

performance dimension. Mercedes automobiles

are valuable because

the

perceived

benefits of ownership, including engineering

performance, reliability, and

prestige, exceed the

price

paid. On the other hand, outputs that

cost little to produce are

valuable because of their

ability to

satisfy

customer demands at a low

price. Chevrolet automobiles

are valuable because they

provide basic

transportation

at a low price. Mercedes and

Chevrolet are both

profitable, but achieve that

outcome

through

different value propositions.

Imitability.

Finally, sustainable competitive

advantage is achieved when unique and

valuable resources

and

processes

are difficult to mimic or duplicate by

other organizations. For

example, organizations can

protect

their

competitive advantage by making it

difficult for other firms to

identify their distinctive

competence.

Disclosing

unimportant information at trade

shows or forgoing superior profits

can make it difficult

for

competitors

to identify an organization's strengths.

Organizations can aggressively

pursue a range of

opportunities,

thus raising the cost for

competitors who try to replicate

their success. Organizations

can

seek

to retain key human resources

through attractive compensation and

reward practices, thereby making

it

more difficult and costly

for competitors to attract such

talent.

Collective

Responses

Organizations

can cope with problems of

environmental dependence and uncertainty

through increased

coordination

with other organizations. Collective

responses help control

interdependencies among

organizations

and include such methods as bargaining;

contracting; coopting; and creating

joint ventures,

federations,

strategic alliances, and

consortia. Contemporary organizations

increasingly are turning to

joint

ventures

and partnerships with other

organizations to manage environmental

uncertainty and perform

tasks

that

are too costly and

complicated for single

organizations to perform. These

multiorganization

arrangements

are being used as a means of

sharing resources for

large-scale research and development,

for

spreading

the risks of innovation, for

applying diverse expertise to complex

problems and tasks, and

for

overcoming

barriers to entry into

foreign markets. For

example, pharmaceutical firms are

forming strategic

alliances

to distribute noncompeting medications

and avoid the high costs of

establishing sales

organizations;

firms from different countries

are forming joint ventures

to overcome restrictive trade

barriers;

and high-technology firms are

forming research consortia to

undertake significant and

costly

research

and development for their

industries.

Major

barriers to collective responses in the

United States are

organizations' drive to act autonomously

and

government

policies discouraging coordination

among organizations, especially in the

same industry. On

the

other hand, Japanese

industrial and economic

policies promote cooperation among

organizations, thus

giving

them a competitive advantage in responding to complex

and dynamic global environments.

For

example,

the Japanese government traditionally has

provided financial assistance and support

to

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

cooperative

research efforts among

Japanese consumer product

manufacturers. The resulting

technological

developments

enabled such firms as Matsushita,

Canon, and Sony to reduce

American competitors' market

shares

dramatically.

The

three interventions discussed

here derive from this organization and

environment framework. They

help

organizations assess their environments

and make appropriate responses to

them. The first

intervention,

integrated strategic change, focuses on

how to coordinate administrative and

competitive

responses

for a single organization or strategic

business unit. The next

two interventions,

transorganization

development

and mergers and

acquisitions, broaden the scope from

single to multiple organizations.

These

interventions

endeavor to coordinate administrative, competitive,

and collective responses.

Integrated

Strategic Change

Integrated

Strategic Change (ISC) is a recent

intervention that brings an OD

perspective to traditional

strategic

planning. It was developed in response to

managers' complaints that

good business strategies

often

are

not implemented. The research

suggested that too little

attention was being given to the change

process

and

human resources issues

necessary to execute the strategy.

For example, the predominant

paradigm in

strategic

planning and implementation

artificially separates strategic

thinking from operational arid

tactical

actions;

it ignores the contributions that planned

change processes can make to

implementation. In the

traditional

process, senior managers and

strategic planning staff prepare

economic forecasts,

competitor

analyses,

and market studies. They

discuss these studies and

rationally align the firm's strengths

and

weaknesses

with the environmental opportunities

and threats to form the

organization's strategy.

Implementation

occurs as middle managers,

supervisors, and employees

hear about the new

strategy

through

memos, restructuring announcements,

changes in job responsibilities, or

new departmental

objec-

tives.

Consequently, because participation

has been limited to top

management, there is little

understanding

of

the need for change and

little ownership of the new behaviors,

initiatives, and tactics required to

achieve

the

announced objectives.

Key

Features

ISC,

in contrast, was designed to be a

highly participative process. It has

three key features:

1.

The relevant unit of analysis is the

organization's strategic orientation

comprising its strategy

and

organization

design. Strategy and the

design that supports it must

be considered as an integrated whole.

2.

Creating the strategic plan, gaining commitment

and support for it, planning

its implementation, and

executing

it are treated as one integrated

process. The ability to

repeat such a process

quickly and

effectively

when

conditions warrant represents a

sustainable competitive

advantage.

3.

Individuals and groups

throughout the organization are integrated

into the analysis, planning,

and

implementation

process to create a more

achievable plan, to maintain the firm's strategic

focus, to direct

attention

and resources on the organization's

key competencies, to improve

coordination and

integration

within

the organization, and to create higher

levels of shared ownership and

commitment.

Application

Stages

The

ISC process is applied in four phases:

performing a strategic analysis,

exercising strategic

choice,

designing

a strategic change plan, and implementing

the plan. The four steps are

discussed sequentially

here

but

actually unfold in overlapping

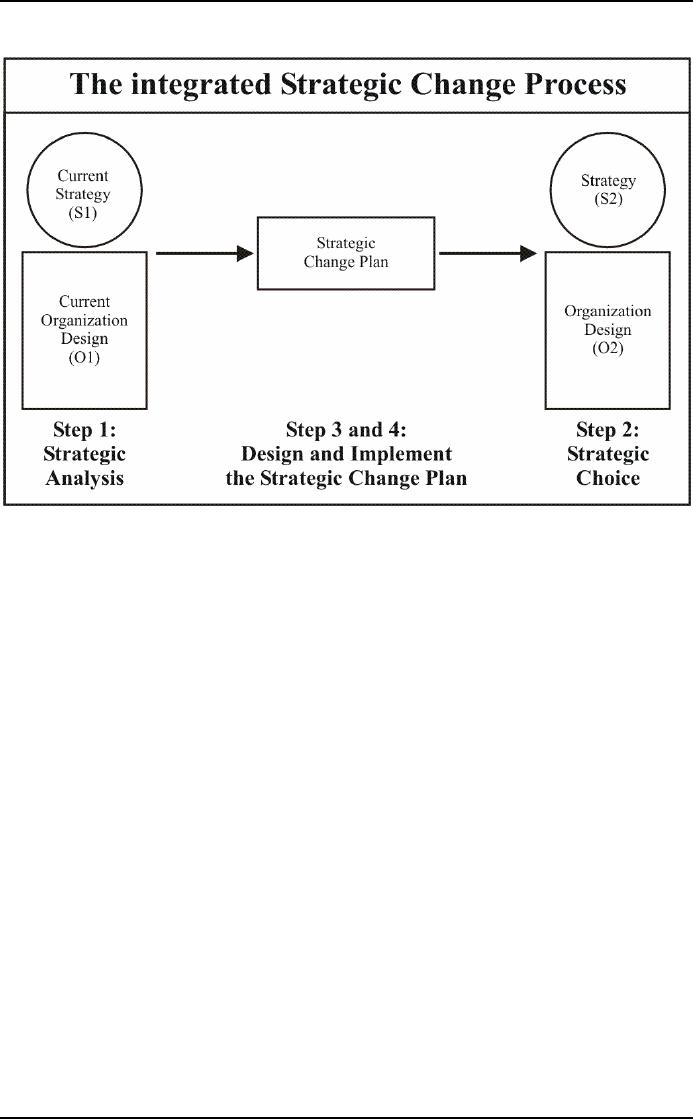

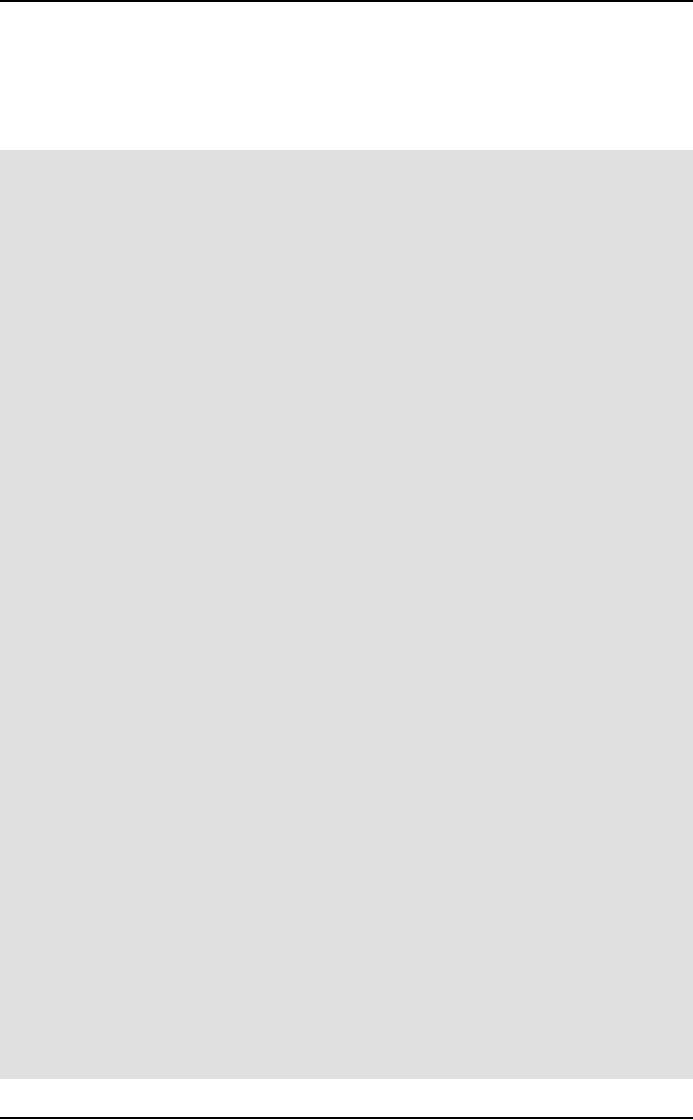

and integrated ways. Figure 59 displays

the steps in the ISC process

and

its

change components. An organization's

existing strategic orientation,

identified as its current strategy

(SI)

and

organization design (OI), are

linked to its future

strategic orientation (S2/O2) by the

strategic change

plan.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Figure

59

1.

Performing the strategic

analysis. The

ISC process begins with a

diagnosis of the organization's

readiness

for change and its current

strategy and organization (S1/O1).

The most important indicator

of

readiness

is senior management's willingness

and ability to carry out

strategic change. Organizations

whose

leaders

are not willing to lead

and whose senior managers

are not willing and

able to support the new

strategic

direction when necessary should consider

team-building processes to ensure their

commitment.

The

second stage in strategic

analysis is understanding the current

strategy and organization design.

The

process

begins with an examination of the

organization's industry as well as its

current financial

performance

and effectiveness. This information

provides the necessary context to assess

the current

strategic

orientation's viability. Next, the current

strategic orientation is described to

explain current levels

of

performance and human

outcomes. Several models for

guiding this diagnosis exist.

For example, the

strategy

is represented by the organization's

mission, goals and

objectives, intent, and

business policies.

The

organization

design is described by the structure,

work, information, and human

resource systems.

Other

models

for understanding the organization's

strategic orientation include the

competitive positioning model

and

other typologies. These frameworks

assist in assessing customer

satisfaction; product and

service

offerings;

financial health; technological capabilities; and

organizational culture, structure, and

systems.

Strategic

analysis actively involves organization members in the

process. Search conferences;

employee

focus

groups; interviews with salespeople,

customers, purchasing agents;

and other methods allow a

variety

of

employees and managers to participate in

the diagnosis and increase the amount

and relevance of the

data

collected. This builds commitment to and ownership of

the analysis; should a strategic change

effort

result,

members are more likely to

understand why and be

supportive of it.

2.

Exercising strategic choice. Once

the existing strategic orientation is understood, a

new one must be

designed.

For example, the strategic

analysis may reveal misfits

among the organization's

environment,

strategic

orientation, and performance.

These misfits can be used as inputs to

workshops where the

future

strategy

and organization design are

crafted. Based on this analysis,

senior management formulates

visions

for

the future and broadly

defines two or three alternative

sets of objectives and

strategies for

achieving

those

visions. Market forecasts,

employees' readiness and

willingness to change, competitor

analyses, and

other

projections can be used to develop the alternative

future scenarios. The

different sets of

objectives

and

strategies also include projections about the

organizational design changes that

will be necessary to

support

each alternative. Although participation

from other organizational stakeholders is

important in the

alternative

generation phase, choosing the appropriate

strategic orientation ultimately

rests with top

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

management

and cannot easily be delegated.

Senior executives are in the unique

position of viewing

strategy

from a general management

position. When major strategic

decisions are given to lower-level

managers,

the risk of focusing too narrowly on a

product, market, or technology

increases.

This

step determines the content or "what" of

strategic change. The

desired strategy (S2)

defines the

products

or services to offer, the markets to be

served, and the way these

outputs will be produced

and

positioned.

The desired organization design (O2)

specifies the organizational structures

and processes

necessary

to support the new strategy.

Aligning an organization's design

with a particular strategy can be

a

major

source of superior performance and

competitive advantage.

3.

Designing the strategic change

plan. The

strategic change plan is a comprehensive

agenda for

moving

the organization from its current

strategy and organization design to the

desired future

strategic

orientation.

It represents the process or "how" of

strategic change. The change

plan describes the

types,

magnitude,

and schedule of change

activities, as well as the costs

associated with them. It

also specifies how

the

changes will be implemented, given power

and political issues, the

nature of the organizational culture,

and

the current ability of the organization to implement

change.

4.

Implementing the strategic

change plan. The

final step in the ISC

process is the actual

implementation

of the strategic change plan. This draws

heavily on knowledge of motivation,

group

dynamics,

and change processes. It

deals continuously with such

issues as alignment, adaptability,

teamwork,

and organizational and personal learning.

Implementation requires senior

managers to champion

the

different elements of the change plan.

They can, for example,

initiate action and allocate

resources to

particular

activities, set high but

achievable goals, and

provide feedback on accomplishments. In

addition,

leaders

must hold people accountable to the

change objectives, institutionalize

each change that occurs,

and

be

prepared to solve problems as they

arise. This final point

recognizes that no strategic

change plan can

account

for all of the contingencies

that emerge. There must be a

willingness to adjust the plan

as

implementation

unfolds to address unforeseen

and unpredictable events and to

take advantage of new

opportunities.

Transorganizational

Development

Transorganizational

development (TD) is a form of planned

change aimed at helping

organizations develop

collective

and collaborative strategies with

other organizations. Many of the

tasks, problems, and

issues

facing

organizations today are too complex

and multifaceted to be addressed by a

single organization.

Multiorganization

strategies and arrangements

are increasing rapidly in

today's highly competitive, global

environment.

In the private sector, research

and development consortia allow

companies to share

resources

and

risks associated with

large-scale research efforts.

For example, Sematech

involved many large

organizations,

such as Intel, AT&T, IBM,

Xerox, and Motorola, that

joined together to improve the

competitiveness

of the U.S. semiconductor industry.

Joint ventures, such as

Fuji-Xerox, between

domestic

and

foreign firms can help

overcome trade barriers and

facilitate technology transfer across

nations. The

New

United Motor Manufacturing,

Inc., in Fremont, California, for

example, is a joint venture

between

General

Motors and Toyota to produce

automobiles using Japanese teamwork

methods.

Transorganizational

Systems and their Problems

Transorganizational

systems (TSs) are groups of

organizations that have

joined together for a common

purpose.

TSs include a range of collective

responses, including licensing

agreements, strategic

alliances,

joint

ventures, and public-private

partnerships. They are

functional social systems existing

intermediately

between

single organizations and

societal systems. TSs make

decisions and perform tasks

on behalf of their

member

organizations, although members maintain

their separate organizational identities

and goals. This

separation

distinguishes them from mergers

and acquisitions. In contrast to

most organizations, TSs

tend

to

be under organized: relationships among

member organizations are

loosely coupled; leadership

and

power

are dispersed among autonomous

organizations, rather than hierarchically

centralized; and com-

mitment

and membership are tenuous

as member organizations act to maintain

their autonomy while

jointly

performing.

These

characteristics make creating

and managing TSs difficult.

Potential member organizations

may not

perceive

the need to join with other

organizations. They may be

concerned with maintaining

their

autonomy

or have trouble identifying

potential partners. U.S. firms,

for example, are

traditionally "rugged

individualists''

preferring to work alone rather

than to join with other

organizations. Even if

organizations

decide

to join together, they may have

problems managing their relationships

and controlling joint

performances.

Because members typically

are accustomed to hierarchical forms of

control, they may

have

difficulty

managing lateral relations among

independent organizations. They also may

have difficulty

managing

different levels of commitment and

motivation among members and

sustaining membership

over

time.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Application

Stages

Given

these problems, trans-organizational development

has evolved as a unique form of planned

change

aimed

at creating TSs and

improving their effectiveness.

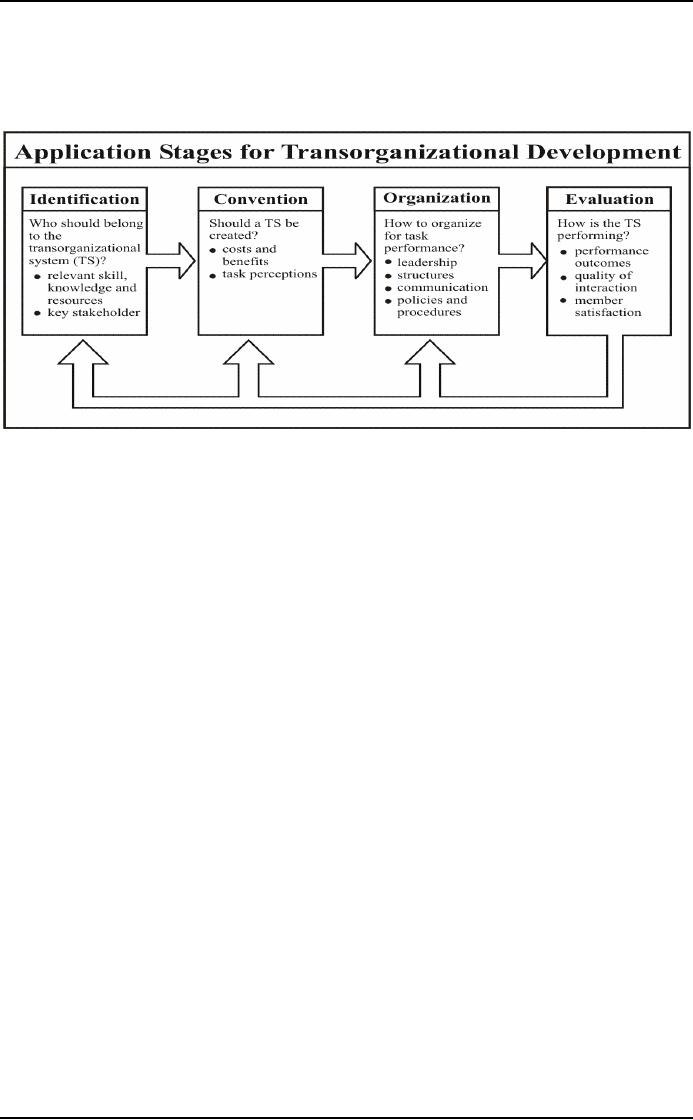

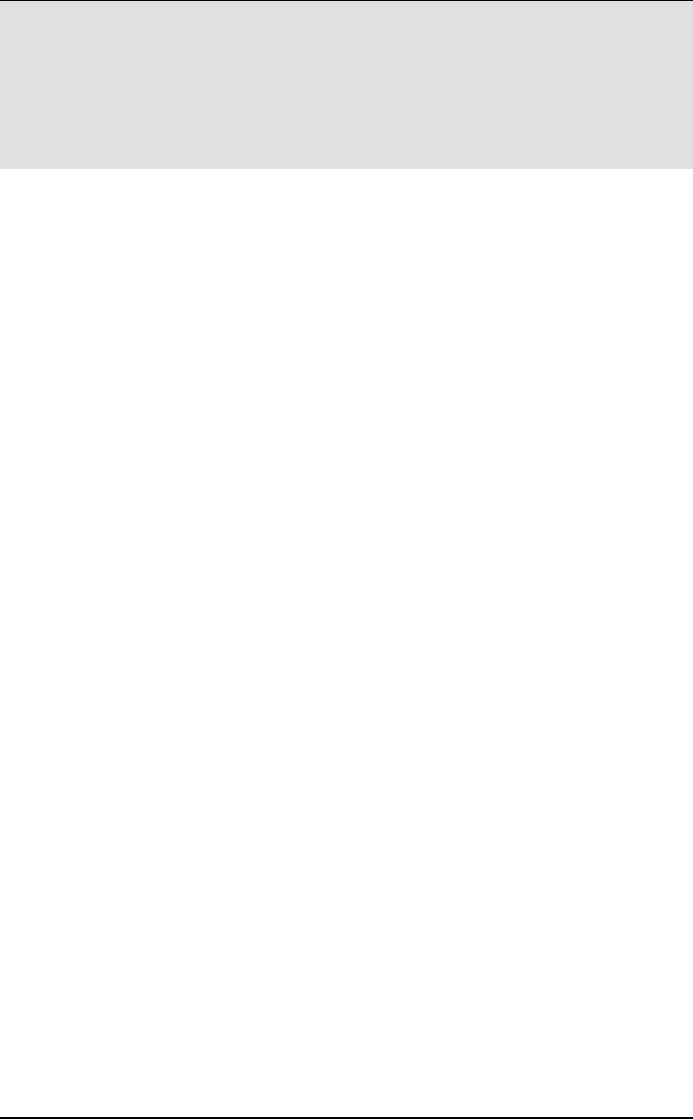

The four stages are

shown in Figure 60, along

with

key

issues that need to be

addressed at each

stage.

Figure

60

The

stages and issues are

described below.

1.

Identification stage. This

initial stage of TD involves

identifying potential member

organizations of the

TS.

For example, in the case of a

strategic alliance or joint venture, this

stage involves identifying the

potential

partners best suited to

achieving the organization's objectives.

Identifying potential members

can

be

difficult because organizations

may not perceive the need to

join together or may not

know enough

about

each other to make

membership choices. These

problems are typical when trying to

create a new TS.

Relationships

among potential members may

be loosely coupled or nonexistent; thus,

even if organizations

see

the need to form a TS, they

may be unsure about who

should be included.

The

identification stage is generally

carried out by one or a few

organizations interested in exploring

the

possibility

of creating a TS. Change

agents work with these

initiating organizations to clarify

their own

goals,

such as product or technology exchange,

learning, or market access; to explore

alternatives to

collaboration,

including internal development,

purchasing skills or resources, or making

an acquisition; and

understanding

the tradeoff between the loss of autonomy

and the value of collaboration. OD

practitioners

also

help specify criteria for

membership in the TS and identify

organizations meeting those

standards. Be-

cause

TSs are intended to perform

specific tasks, a practical

criterion for membership is

how much

organizations

can contribute to task

performance. Potential members

can be identified and judged in

terms

of

the skills, knowledge, and resources

that they bring to bear on the TS

task. TD practitioners warn,

however,

that identifying potential

members also should take

into account the political

realities of the

situation.

Consequently, key stakeholders

who can affect the creation and

subsequent performance of the

TS

are identified as possible

members.

During

the early stages of creating a

TS, there may be

insufficient leadership and

cohesion among

participants

to choose potential members. In

these situations, participants may

contract with an outside

change

agent who can help them

achieve sufficient agreement on TS

membership. In several cases of

TD,

change

agents helped members to create a

special leadership group

that could make decisions on behalf

of

the

participants. This leadership

group comprised a small

cadre of committed members and

was able to

develop

enough cohesion among members to

carry out the identification

stage.

2.

Convention stage. Once

potential members of the TS are

identified, the convention stage is

concerned

with

bringing them together to assess whether

creating a TS is desirable and

feasible. This

face-to-face

meeting

enables potential members to explore

mutually their motivations

for joining and their

perceptions

of

the joint task. They work to

establish sufficient levels of

motivation and of task

consensus to form the

TS.

Like

the identification stage, this phase of

TD generally requires considerable

direction and facilitation

by

change

agents. Existing stakeholders

may not have the legitimacy

or skills to perform the convening

function,

and change agents can

serve as conveners if they are

perceived as legitimate and credible by

the

attending

organizations. In many TD cases,

conveners came from research

centers or universities

with

reputations

for neutrality and expertise

in TD. Because participating

organizations tend to have

diverse

motives

and views and limited

means for resolving differences,

change agents may need to

structure and

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

manage

interactions to facilitate airing of differences

and arriving at consensus

about forming the TS.

They

may

need to help organizations

work through differences and

reconcile self-interests with

those of the

larger

TS.

3.

Organization stage. When

the convention stage results in a

decision to create a TS,

members then

begin

to organize themselves for

task performance. This involves

establishing structures and

mechanisms

that

promote communication and interaction

among members and that

direct joint efforts to the task

at

hand.

For example, members may

create a coordinating council to manage

the TS, and they might

assign a

powerful

leader to head that group. They

might choose to formalize exchanges

among members by

developing

rules, policies, and formal

operating procedures. When members

are required to invest large

amounts

of resources in the TS, such as

might occur in an industry-based

research consortium, the

organizing

stage typically includes

voluminous contracting and negotiating

about members'

contributions

and

returns. Here, corporate lawyers and

financial analysts play key roles in

structuring the TS. They deter-

mine

how costs and benefits will

be allocated among member

organizations as well as the legal

obligations,

decision-making

responsibilities, and contractual rights

of members.

In

the case of strategic alliances

and joint ventures, explicit

strategies must be created

for how the TS will

perform

its work. Change agents

can help members define

competitive advantage for the TS as

well as the

structural

requirements necessary to support

achievement of its

goals.

4.

Evaluation stage. This

final stage of TD involves assessing

how the TS is performing. Members

need

feedback

so that they can identify

problems and begin to resolve

them. Feedback data

generally include

performance

outcomes and member

satisfactions, as well as indicators of

how well members are

interacting

jointly.

Change agents, for example,

can periodically interview or survey

member organizations

about

various

outcomes and features of the TS

and feed that data

back to TS leaders. Such

information will

enable

leaders to make necessary operational

modifications and adjustments. It

may signal the need

to

return

to previous stages of TD to make

necessary corrections, as shown by the

feedback arrows in Figure

60.

Roles

and Skills of the Change

Agent

Trans-organizational

development is a relatively new application of planned

change, and practitioners

are

still

exploring appropriate roles and

skills. They are discovering the

complexities of working with

under

organized

systems comprising multiple

organizations. This contrasts sharply

with OD, which

has

traditionally

been applied in single organizations

that are heavily organized.

Consequently, the roles

and

skills

relevant to OD need to be modified and

supplemented when applied to

TD.

The

major role demands of TD derive from the

two prominent features of

TSs: their under organization

and

their multi-organization composition.

Because TSs are under

organized, change agents

need to play

activist

roles in creating and developing

them. They need to bring

structure to a group of

autonomous

organizations

that may not see the need to

join together or may not

know how to form an

alliance. The

activist

role requires a good deal of

leadership and direction, particularly

during the initial stages of

TD. For

example,

change agents may need to

educate potential TS members about the

benefits of joining together.

They

may need to structure

face-to-face encounters aimed at

sharing information and

exploring interaction

possibilities.

Because

TSs are composed of multiple

organizations, change agents

need to maintain a neutral role,

treating

all members alike. They need

to be seen by members as working on

behalf of the total

system,

rather

than as being aligned with particular

members or views. When

change agents are perceived

as

neutral,

TS members are more likely

to share information with them

and to listen to their inputs.

Such

neutrality

can enhance change agents'

ability to mediate conflicts among

members. It can help

them

uncover

diverse views and interests

and forge agreements among

stakeholders. Change agents,

for example,

can

act as mediators, ensuring

that members' views receive

a fair hearing and that

disputes are equitably

resolved.

They can help to bridge the

different views and

interests and achieve integrative

solutions.

Given

these role demands, the

skills needed to practice TD include

political and networking

abilities.

Political

competence is needed to understand

and resolve the conflicts of interest

and value dilemmas

inherent

in systems made up of multiple

organizations, each seeking to maintain

autonomy while jointly

interacting.

Political

savvy can help change

agents manage their own

roles and values in respect

to those power

dynamics.

It can help them to avoid being coopted

by certain TS members and

thus losing their

neutrality.

Networking

skills are also

indispensable to TD practitioners. These include the

ability to manage

lateral

relations

among autonomous organizations in the

relative absence of hierarchical control.

Change agents

must

be able to span the boundaries of

diverse organizations, link them

together, and facilitate exchanges

among

them. They must be able to

form linkages where none

existed and to transform networks

into

operational

systems capable of joint

task performance.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Defining

the roles and skills of TD practitioners

is still in a formative stage.

Our knowledge in this area

will

continue

to develop as more experience is gained

with TSs. Change agents

are discovering, for

example,

that

the complexity of TSs requires a

team consulting approach, involving

practitioners with different

skills

and

approaches working together to promote TS

effectiveness. Initial reports of TD

practice suggest that

such

change projects are large

scale and long term,

typically involving multiple,

simultaneous interventions

aimed

at both the total TS and its

constituent members. The stages of TD

application are protracted,

requiring

considerable time and effort to

identify relevant organizations, to

convene them, and to

organize

them

for task performance.

Mergers

and Acquisitions

Mergers

and acquisitions (M&As) involve the

combination of two organizations.

The term merger refers

to

the

integration of two previously independent

organizations into a completely new

organization; acquisition

involves

the purchase of one organization by another

for integration into the acquiring

organization. M&As

are

distinct from TSs, such as

alliances and joint

ventures, because at least

one of the organizations

ceases

to

exist.

M&A

Rationale

Organizations

have a number of reasons for wanting to

acquire or merge with other

firms, including

diversification

or vertical integration; gaining access to

global markets, technology, or other

resources; and

achieving

operational efficiencies, improved

innovation, or resource sharing. As a

result, M&As have

become

a preferred method for rapid

growth and strategic

change.

M&A

interventions typically are

preceded by an examination of corporate and

business strategy. Corporate

strategy

describes the range of businesses

within which the firm will

participate, and business

strategy

specifies

how the organization will compete in

any particular business. Organizations

must decide whether

their

corporate and strategic goals should be

achieved through administrative or

competitive responses,

such

as ISC, or through collective responses,

such as TD or M&As. Mergers and

acquisitions are preferred

when

internal development is too slow, or when

alliances or joint ventures do

not offer sufficient

control

over

key resources to meet the firm's

objectives.

M&As

are complex strategic changes

that involve various legal

and financial requirements beyond

the

scope

of this text.

Application

Stages

Mergers

and acquisitions involve

three major phases as shown in

Table 23: pre-combination,

legal

combination,

and operational combination. OD practitioners

can make substantive

contributions to the

pre-combination

and operational combination phases as

described below.

Pre-combination

Phase

This

first phase consists of

planning activities designed to

ensure the success of the combined

organizations.

The organization that initiates the

strategic change must

identify a candidate organization;

work

with it to gather information

about each other, and plan

the implementation and integration

activities.

The

evidence is growing that

pre-combination phase activities are

critical to M&A success.

1.

Search for and select candidate.

This

involves developing screening criteria to

assess and narrow the

field

of candidate organizations, agreeing on a

first-choice candidate, assessing regulatory

compliance,

establishing

initial contacts, and

formulating a letter of intent. Criteria

for choosing an M&A partner can

in-

clude

leadership and management

characteristics, market access

resources, technical or financial

capabilities,

physical

facilities, and so on. OD practitioners

can add value at this stage

of the process by encouraging

screening

criteria that include managerial, organizational,

and cultural components as well as

technical and

financial

aspects. In practice, financial issues

tend to receive greater

attention at this stage, with the

goal of

maximizing

shareholder value. Failure to attend to cultural

and organizational issues, however, can

result in

diminished

shareholder value during the operational

combination phase.

Identifying

potential candidates, narrowing the

field, agreeing on a first

choice, and checking

regulatory

compliance

are relatively straightforward activities. They

generally involve investment brokers and

other

outside

parties who have access to

databases of organizational, financial, and

technical information.

The

final

two activities, making initial

contacts and creating a

letter of intent, are aimed

at determining the

candidate's

interest in the proposed merger or

acquisition.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Table

23

Major

Phases and Activates in Merger and

Acquisitions

Major

M &A

OD

And

Change

phases

Key

Steps

Management

Issues

�

Search

for and select

�

Ensure

that candidates

Precombination

candidate.

are

screened

for

�

Create

M & A team.

cultural

as well as

functional

technical,

�

Establish

business case.

physical

asset criteria.

�

Perform

due diligence

�

Define

clear leadership

assessment.

structure.

�

Develop

merger

�

Establish

a

clear

integration

plan.

strategic

vision

competitive

strategy

and

system integration

potential.

�

Specify

the desirable

organization

design

features.

�

Specify

an integration

action

plan.

�

Complete

Legal

combination

financial

negotiations.

�

Close

deal.

�

Announce

the

combination.

�

Day

I activities.

�

Implement

Operational

combination

change

�

Organizational

quickly.

and

�

Communications.

technical

integration

�

Solve

problem together

activities.

�

Cultural

integration

and

focus on customer.

�

Conduct an

evaluation

activities.

to

learn and identify

further

areas

of

integration

planning.

.

2.

Create an M&A team. Once

there is initial agreement

between the two organizations to

pursue a

merger

or acquisition, senior leaders from the

respective organizations appoint an

M&A team to establish

the

business case, to oversee the

due diligence process, and

to develop a merger integration plan.

This team

typically

comprises senior executives

and experts in such areas as

business valuation, technology,

organization,

and marketing. OD practitioners can facilitate

formation of this team through

human process

interventions,

such as team building and

process consultation, and help the

team establish clear goals

and

action

strategies. They also can

help members define a clear

leadership structure, apply relevant

skills and

knowledge,

and ensure that both

organizations are represented

appropriately. The group's

leadership

structure,

or who will be accountable

for the team's accomplishments, is

especially critical. In an

acquisition,

an executive from the acquiring firm is

typically the team's leader. In a

merger of equals, the

choice

of a single individual to lead the

team is more difficult, but

must be made. The outcome of

this

decision

and the process used to make

it form the first outward

symbol of how this strategic

change will be

conducted.

3.

Establish the business

case. The

purpose of this activity is to develop a prima

facie case that

combining

the two organizations will

result in a competitive advantage

that exceeds their

separate

advantages.

It includes specifying the strategic

vision, competitive strategy,

and systems

integration

potential

for the M&A. OD practitioners can facilitate this

discussion to ensure that

each issue is fully

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

explored.

If the business case cannot be justified

on strategic, financial, and operational

grounds, the M&A

should

be revisited, terminated, or another candidate should be

sought.

Strategic

vision represents the organizations'

combined capabilities. It synthesizes the

strengths of the two

organizations

into a viable new organization.

Competitive

strategy describes the business model

for how the combined organization will

add value in a

particular

product market or segment of the

value chain, how that

value proposition is best

performed by

the

combined organization (compared with competitors),

and how that proposition

will be difficult to

imitate.

The purpose of this activity is to force

the two organizations to go beyond the

rhetoric of "these

two

organizations should merge because

it's a good fit.

Systems

integration specifies how the

two organizations will be combined. It

addresses how and if they

can

work

together. It includes such

key questions as Will one

firm be acquired and

operated as a wholly owned

subsidiary?

Does the transaction imply a

merger of equals? Are layoffs

implied, and if so, where?

On what

basis

can promised synergies or

cost savings be

achieved?

4.

Perform a due diligence

assessment. This

involves evaluating whether the two

organizations actually

have

the managerial, technical, and

financial resources that

each assumes the other

possesses. It includes a

comprehensive

review of each organization's articles of

incorporation, stock option

plans, organization

charts,

and so on. Financial, human

resources, operational, technical, and

logistical inventories are

evaluated

along

with other legally binding

issues. The discovery of previously

unknown or unfavorable information

can

stop the M&A process from going

forward.

Although

due diligence assessment

traditionally emphasizes the financial

aspects of M&As, this focus is

increasingly

being challenged by evidence that culture

clashes between two

organizations can ruin

expected

financial

gains. Thus, attention to the cultural

features of M&As is becoming more

prevalent in due

diligence

assessment.

The

scope and detail of due

diligence assessment depend on knowledge

of the candidate's business, the

complexity

of its industry, the relative size

and risk of the transaction, and the

available resources.

Due

diligence

activities must reflect symbolically the vision

and values of the combined organizations.

An overly

zealous

assessment, for example, can

contradict promises of openness and trust

made earlier in the

transaction.

Missteps at this stage can

lower or destroy opportunities

for synergy, cost savings,

and

improved

shareholder value.

5.

Develop merger integration

plans. This

stage specifies how the two

organizations will be combined. It

defines

integration objectives; the scope

and timing of integration

activities; organization design

criteria;

Day

1 requirements; and who does

what, where, and when. The

scope of these plans depends

on how

integrated

the organizations will be. If the

candidate organization will operate as an

independent subsidiary

with

an "arm's-length" relationship to the parent, merger

integration planning need

only specify those

systems

that will be common to both

organizations. A full integration of the

two organizations requires

a

more

extensive plan.

Merger

integration planning starts

with the business ease

conducted earlier and involves

more detailed

analyses

of the strategic vision, competitive

strategy, and systems

integration for the M&A. For

example,

assessment

of the organizations' markets and

suppliers can reveal

opportunities to serve customers

better

and

to capture purchasing economies of

scale, examination of business processes

can identify best

operating

practices; which physical facilities

should be combined, left alone, or shutdown;

and which

systems

and procedures are redundant. Capital

budget analysis can show

which investments should be

continued

or dropped. Typically, the M&A team appoints

subgroups composed of members

from both

organizations

to perform these analyses.

OI) practitioners can conduct team

building and process

consultation

interventions to improve how

those groups

function.

Next,

plans for designing the combined

organization are developed. They include the

organization's

structure,

reporting relationships, human

resource's policies, information

and control systems,

operating

logistics,

work designs, and

customer-focused activities.

The

final task of integration

planning involves developing an action plan for

implementing the M&A. This

specifies

tasks to be performed, decision-making

authority and responsibility,

and timelines for

achievement.

It also includes a process

for addressing conflicts and

problems that will

invariably arise

during

the implementation process.

Legal

Combination Phase

This

phase of the M&A process involves the

legal and financial aspects

of the transaction. The

two

organizations

settle on the terms of the deal,

register the transaction with

and gain approval

from

appropriate

regulatory agencies, communicate with

and gain approval from

shareholders, and

file

appropriate

legal documents. In some

cases, an OD practitioner can

provide advice on negotiating a

fair

agreement,

but this phase generally

requires knowledge and expertise beyond

that typically found in

OD

practice.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Operational

Combination Phase

This

final phase involves implementing the

merger integration plan. In practice, it

begins during due

diligence

assessment and may continue

for months or years following the

legal combination phase.

M&A

implementation

includes the three kinds of activities

described below.

1.

Day 1 activities.

These include communications and

actions that officially

start the implementation

process.

For example, announcements

may be made about key

executives of the combined organization,

the

location of corporate headquarters, the

structure of tasks, and

areas and functions where

layoffs will

occur.

M&A practitioners pay special

attention to sending important

symbolic messages to organization

members,

investors, and regulators about the

soundness of the merger plans

and those changes that

are

critical

to accomplishing strategic and

operational objectives.

2.

Operational and technical integration

activities.

These involve the physical

moves, structural

changes,

work designs, and procedures

that will be implemented to accomplish

the strategic objectives

and

expected

cost savings of the M&A. The

merger integration plan

lists these activities,

which can be large in

number

and range in scope from

seemingly trivial to quite critical.

For example, American

Airlines'

acquisition

of Reno Air involved

changing Reno's employee

uniforms, the signage at all airports,

marketing

and

public relations campaigns, repainting

airplanes, and integrating the route

structures, among

others.

When

these integration activities

are not executed properly,

the M&A process can be set

back. American's

poor

job of clarifying the wage

and benefit programs caused

an unauthorized pilot "sickout" that

cancelled

many

flights and left thousands

of travelers stranded. Finally,

integrating the reservation, scheduling,

and

pricing

systems was a critical activity. Failure

to execute this task quickly could

have caused

tremendous

logistical

problems, increased safety

risks, and further alienated

customers.

3.

Cultural integration activities. These

tasks are aimed at building

new values and norms in

the

organization.

Successful implementation melds

both the technical and cultural

aspects of the combined

organization.

For example, members from

both organizations can be

encouraged to solve

business

problems

together, thus addressing operational

and cultural integration issues

simultaneously.

The

M&A literature contains several

practical suggestions for

managing the operational combination

phase.

First,

the merger integration plan should be implemented

sooner rather than later, and

quickly rather than

slowly.

Integration of two organizations

generally involves aggressive financial

targets, short timelines,

and

intense

public scrutiny. Moreover, the change

process is often plagued by culture

clashes and political

fighting.

Consequently, organizations need to

make as many changes as

possible in the first one

hundred

days

following the legal combination

phase. Quick movement in key

areas has several

advantages: it

preempts

unanticipated organization changes that

might thwart momentum in the desired

direction, it

reduces

organization members' uncertainty about when things

will happen, and it reduces

the anxiety of the

activity's

impact on the individual's situation. All

three of these conditions

can prevent desired

collaboration

and

other benefits from occurring.

Second,

integration activities must be

communicated clearly and in a

timely fashion to a variety of

stakeholders,

including shareholders, regulators,

customers, and organization members.

M&As can increase

uncertainty

and anxiety about the future,

especially for members of the

involved organizations who

often

inquire,

"Will I have a job? Will my

job change? Will I have a

new boss?" These kinds of

questions can

dominate

conversations, reduce productive

work, and spoil opportunities

for collaboration. To

reduce

ambiguity,

organizations can provide

concrete answers through a variety of

channels including

company

newsletters,

email and intranet postings,

press releases, video and

in-person presentations, one-on-one

interaction

with managers, and so

on.

Third,

members from both

organizations need to work together to

solve implementation problems

and to

address

customer needs. Such coordinated

tasks can clarify work

roles and relationships; they

can

contribute

to member commitment and motivation.

Moreover, when coordinated activity is

directed at

customer

service, it can assure

customers that their

interests will be considered

and satisfied during

the

merger.

Fourth,

organizations need to assess the

implementation process continually to

identify integration

problems

and needs. The following

questions can guide the

assessment process:

�

Have savings estimated

during pre-combination planning

been confirmed or

exceeded?

�

Has the new entity

identified and implemented shared

strategies or opportunities?

�

Has the new organization been implemented

without loss of key

personnel?

�

Was the merger and

integration process seen as

fair and objective?

�

Is the combined company operating efficiently?

�

Have major problems with

stakeholders been

avoided?

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

�

Did the process proceed

according to schedule?

�

Were substantive integration

issues resolved?

�

Are people highly motivated

(more so than

before)?

Mergers

and acquisitions are among

the most complex and challenging

interventions facing

organizations

and

OD practitioners. Application 12 describes the M&A

process at Daimler-Benz and Chrysler. It

clearly

demonstrates

the importance of cultural issues in mergers

and the role that organization

development can

play

in the process.

Application

12: M&A process at Daimler-Benz and

Chrysler

On

November 17, 1998, Daimler-Benz,

Germany's most revered brand

name, and Chrysler,

America's

number-three

car company, merged to

become the world's fifth-largest

car maker. The $40.5

billion merger

in

the history of the automobile manufacturing

business.

The

process began in the early

1990s when Daimler

executives began asking the

question. Their

question

led to the conclusion that Mercedes automobiles

were reaching the limits of

their market.

Daimler's

marquis name brand made it

difficult to enter emerging

and other high-volume

markets.

Moreover,

if Mercedes remained in a specialized

niche, they might not be

able to benefit quickly from

new

techonoligies.innvators

would have little incentive to

license their advanced technology to a

small market

player.

As a result, Daimler began

looking for a partner who could

increase its scope of

operations.

The

process heated up during the

mid-1990s because of overcapacity in the

global automotive

industry.

Chrysler was the top

candidate because of its

complementary product line

and geographical

distribution.

The two companies began the

first of three rounds of talks in

1995.their first attempt at

working

together was an ill-fated Latin American

joint venture.

Wall

Street gave the merger an instant

blessing. The business case

looked very good along

product,

geography,

and financial lines, but

there were concerns about

the differences in culture. First, there

was

very

little product overlap.

Second,

each company had a strong

geographical presence where the

other was weak.

The

combination

allowed both firms to make a strong

entry into the Latin American

market. Third both

organizations

had healthy balance

sheets.

However,

strong reservations emerged concerning

the cultural fit, organizationally, Chrysler

was a

lean,

centralized, low-cost, producer; Mercedes

was a high-quality, bureaucratic,

and staid organization.

Cultural

artifacts were easy to

identify.

Still,

the two organizations saw

great opportunities in cost

savings, especially in logistics,

purchasing,

and

finance. Subsequent announcements

promised savings of $1.4

billion in the year of

operations.

executive

vice president of global procurement and

supply, the new organization would be

able to optimize

worldwide