|

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

# 41

Developing

and Assisting Members

Workforce

Diversity Interventions

Several

profound trends are shaping

the labor markets of modern

organizations. Researchers suggest

that

contemporary

workforce characteristics are

radically different from what they

were just twenty years

ago.

Employees

represent every ethnic background and

color; range from highly

educated to illiterate; vary in

age

from eighteen, to eighty; may

appear perfectly healthy or may have a

terminal illness; may be

single

parents

or part of dual-income, divorced,

same-sex, or traditional families;

and may be physically

or

mentally

challenged.

Workforce

diversity is more than a euphemism for

cultural or ethnic differences. Such a

definition is too

narrow

and focuses attention away

from the broad range of issues

that a diverse workforce

poses. Diversity

results

from people who bring

different resources and

perspectives to the workplace and who

have distinc-

tive

needs, preferences, expectations,

and lifestyles.42 Organizations must design

human resources

systems

that

account for these

differences if they are to attract

and retain a productive workforce

and if they want

to

turn diversity into a competitive

advantage.

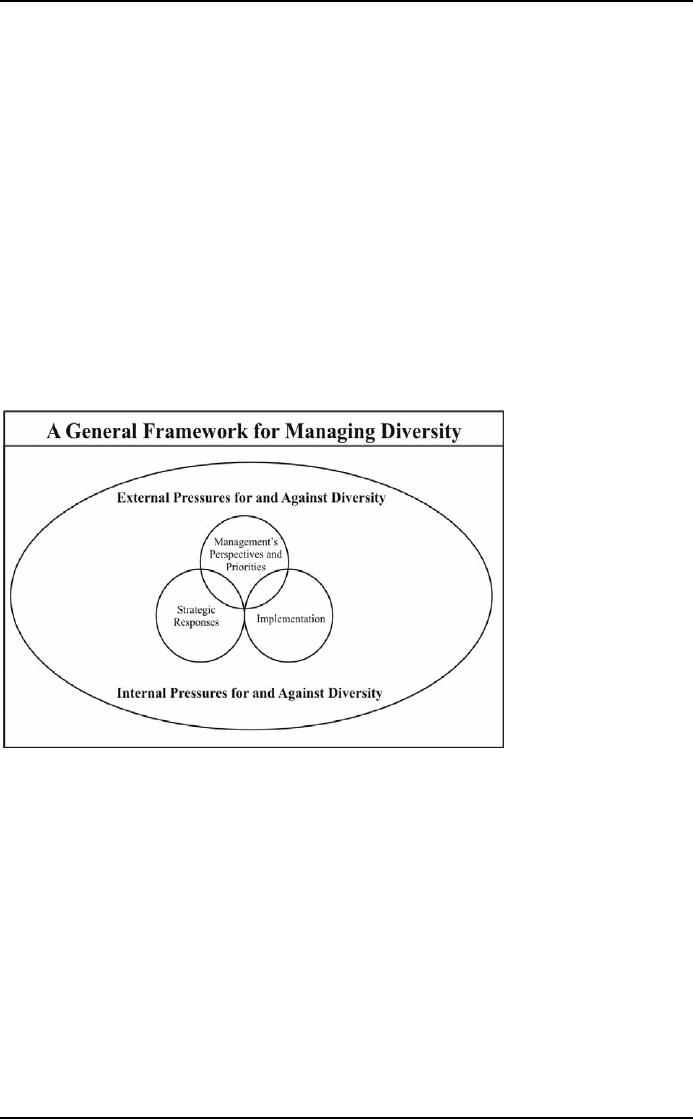

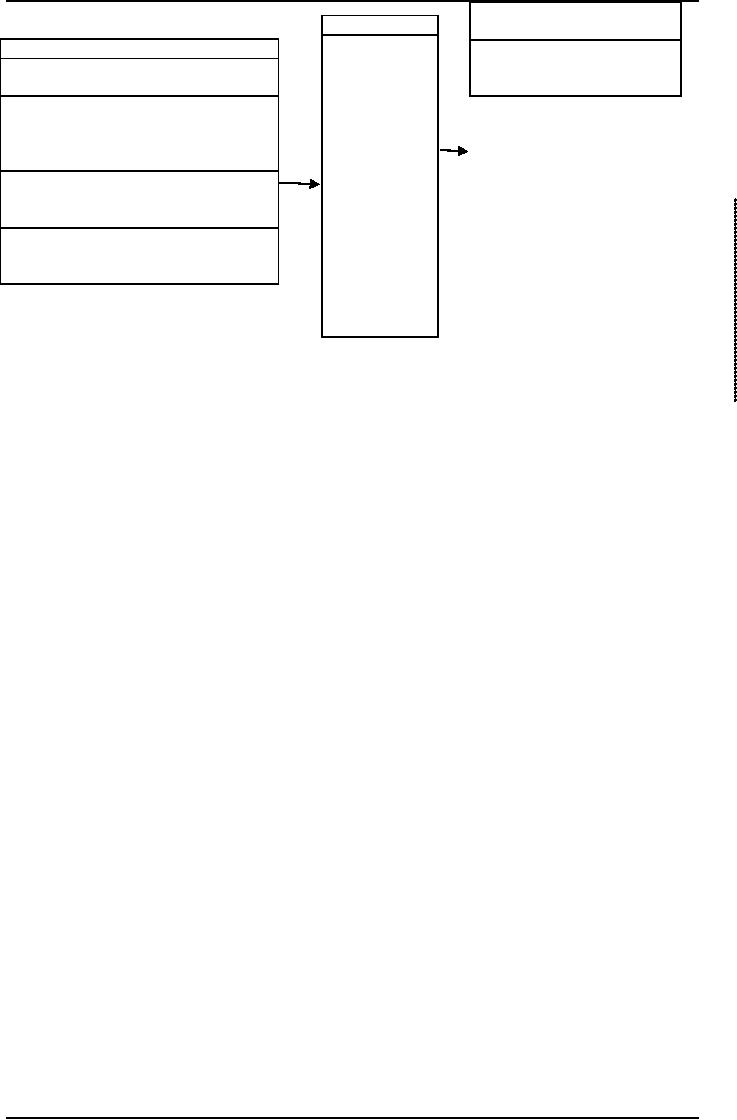

Figure

55 presents a general framework for

managing diversity in

organizations.

Figure

55

First,

the model suggests that an organization's

diversity approach is a function of

internal and external

pressures

for and against diversity.

Pro-diversity forces argue that

organization performance is

enhanced

when

the workforce's diversity is embraced as an

opportunity. But diversity is often

discouraged by those

who

fear that too many

perspectives, beliefs, values,

and attitudes dilute

concerted action.

Second,

management's perspective and

priorities with respect to diversity

can range from resistance

to

active

learning and from marginal to

strategic. For example,

organizations can resist diversity

by

implementing

only legally mandated

policies such as affirmative action,

equal employment opportunity, or

Americans

with Disabilities Act requirements. On

the other hand, a learning and

strategic perspective

can

lead

management to view diversity as a source

of competitive advantage. For

example, a health-care

organization

with a diverse customer base

can improve perceptions of

service quality with

physician

diversity.

Third,

within management's priorities, the

organization's strategic responses

can range from reactive

to

proactive.

Diversity efforts at Texaco

and Denny's had little

momentum until a series of embarrassing

race-

based

events forced a response.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Fourth,

the organization's implementation style

can range from episodic to

systemic. A diversity approach

will

be most effective when the strategic

responses and implementation

style fit with management's

intent

and

internal and external

pressures.

Unfortunately,

organizations have tended to

address workforce diversity pressures in

a piecemeal fashion;

only

5 percent of more than fourteen

hundred companies surveyed

thought they were doing a

"very good

job"

of managing diversity. As each

trend makes itself felt, the organization

influences appropriate practices

and

activities. For example, as the

percentage of women in the workforce

increased, many

organizations

simply

added maternity leaves to their benefits

packages; as the number of physically

challenged workers

increased

and when Congress passed the

Americans with Disabilities Act in

1990, organizations

changed

their

physical settings to accommodate

wheelchairs. Demographers warn, however,

that these trends

are

not

only powerful by themselves

but will likely interact

with each other to force organizational

change.

Thus,

a growing number of organizations, such

as MBNA Corporation, Lockheed Martin, the

St. Paul

Companies,

Levi Strauss, Procter & Gamble,

Monsanto, and Wisconsin Electric,

are taking bolder

steps.

They

are not only adopting

learning perspectives with respect to

diversity, but systemically

weaving

diversity-friendly

values and practices into

the cultural fabric of the organization.

Many

of the QD interventions described in this

book can be applied to the strategic

responses and

implementation

of workforce diversity, as shown in

Table 21. It summarizes

several of the internal

and

external

pressures facing organizations,

including age, gender,

disability, culture and values,

and sexual

orientation.

The table also reports the major trends

characterizing those dimensions,

organizational

implications

and workforce needs, and

specific OD interventions that

can address those

implications.

Age

The

average age of the U.S.

workforce is rising and changing the

distribution of age groups.

Between 1998

and

2008, the category of workers

aged twenty-five to fifty-four

years will grow 5.5

percent and the

fifty-

five

and over age category is

expected to increase almost 48

percent. This skewed

distribution is mostly the

result

of the baby boom between

1946 and 1964. As a result,

organizations will face a

predominantly

middle-aged

and older workforce. Even

now, many organizations are

reporting that the average

age of their

workforce

is over forty. Such a

distribution will place

special demands on the

organization.

For

example, the personal needs

and work motivation of the

different cohorts will require

differentiated

human

resources practices. Older

workers place heavy demands

on health-care services, are

less mobile,

and

will have fewer career

advancement opportunities. This

situation will require specialized

work designs

that

account for physical

capabilities of older workers,

career development activities that

address and use

their

experience, and benefit

plans that accommodate their

medical and psychological

needs. Demand for

younger

workers, on the other hand,

will be intense. To attract

and retain this more mobile group,

jobs will

have

to be more challenging, advancement

opportunities more prevalent, and an

enriched quality of

work

life

more common.

Organization

development interventions, such as work

design, wellness programs

(discussed below), career

planning

and development, and reward

systems must be adapted to

these different age groups.

For the

older

employee, work designs can

reduce the physical components or

increase the knowledge and experi-

ence

components of a job. At Builder's

Emporium, a chain of home

improvement centers, the store

clerk

job

was redesigned to eliminate heavy

lifting by assigning night

crews to replenish shelves

and emphasizing

sales

ability instead of strength.

Younger workers will

likely

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

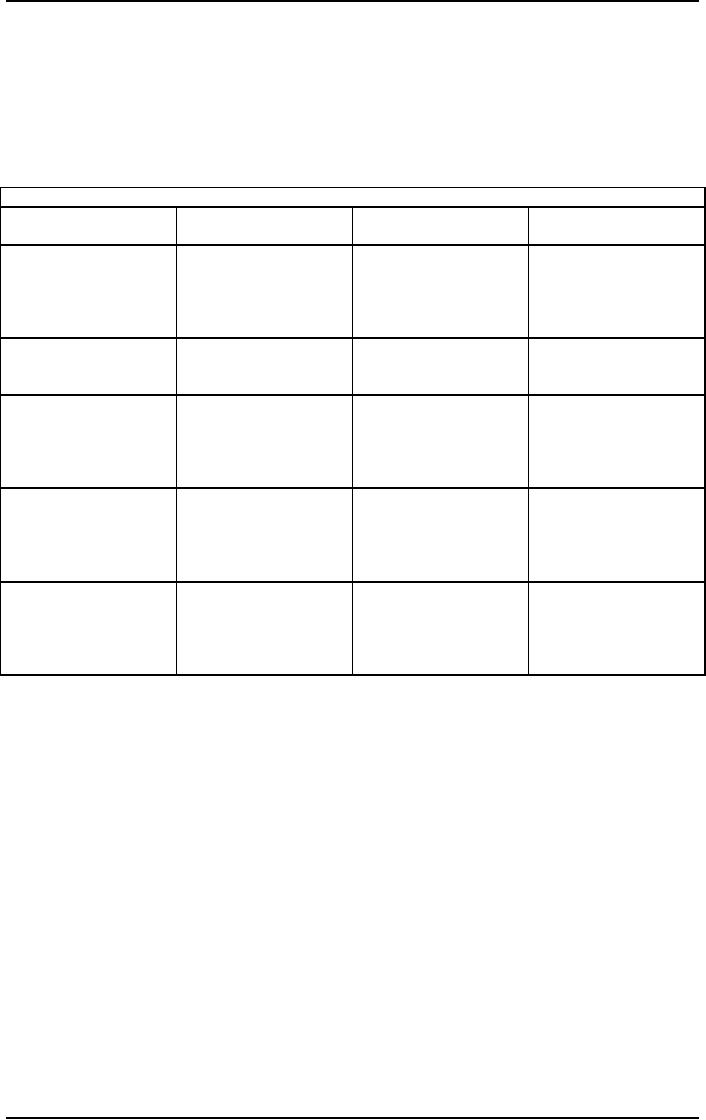

Table

21

Workforce

Diversity Dimensions and Intervention

Work

force

Trends

Implications

Interventions

Difference

And

Needs

Age

Median

age

up

Health care

mobility

Wellness program job

distribution

of ages security

design

changes

Career

planning and

development

reward

system

Gender

Percentage

of women

Child

Care

Job

design

increases

Dual income

Maternity/paternity

Fringe

benefits Rewards

families

leave

single parents

Disability

The

number of people

Job

challenge

Performance

with

disabilities entering

Job

skills

management

the

workforce increasing

Physical

space

Job

design

Respect

and dignity

Career

planning and

development

Culture

and Values

Rising

proportion of

Flexible

organizational Career planning

and

immigrant

and minority

policies

development

group

workers shift in

Autonomy

Employee

involvement

Reward

system

rewards

Affirmation

Respect

Sexual

orientation

Number

of single sex

Discrimination

Equal

employment

households

up

Opportunities

More

liberal Attitude

Fringe

benefits

towards

sexual

Education

and training

orientation

Require

more challenge and autonomy.

Wellness programs can be

used to address the physical

and mental

health

of both generations. Career

planning and development programs

will have to recognize the

different

career

stages of each cohort and

offer resources tailored to

that stage. Finally, reward

system interventions

may

offer increased health benefits, time

off, and other perks

for the older worker while

using promotion,

ownership,

and pay to attract and

motivate the scarcer, younger

workforce.

Gender

Another

important trend is the increasing

percentage of female workers in the

labor force. By the year

2008,

almost 48 percent of the U.S.

workforce will be women, and

they will represent more

than half of the

new

entrants between 1998 and

2008. The organizational implications of

these trends are sobering.

Three-

quarters

of all working women are in

their childbearing years, and

more than half of all

mothers work.

Health-care

costs will likely increase

at even faster rates, and

costs associated with

absenteeism and

turnover

will rise. In addition,

demands for child care,

maternity and paternity leaves,

and flexible working

arrangements

will place pressure on work

systems to maintain productivity and

teamwork. From a

management

perspective, there will be

more men and women

working together as peers, more

women

entering

the executive ranks, greater diversity of

management styles, and

changing definitions of

managerial

success.

Work

design, reward systems, and

career development are among the

more important interventions

for

addressing

issues arising out of the

gender trend. For example,

jobs can be modified to

accommodate the

special

demands of working mothers. A number of

organizations, such as Digital

Equipment, Steel

case,

and

Hewlett-Packard, have instituted job

sharing, by which two people

perform the tasks associated

with

one

job. The firms have done this to

allow their female employees

to pursue both family and

work careers.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Reward

system interventions, especially

fringe benefits, can be tailored to

offer special leaves to

mothers

and

fathers, child-care options,

flexible working hours, and

health and wellness benefits.

Career

development

interventions help maintain, develop, and

retain a competent and diverse

workforce.

Organizations

such as Polaroid, Hoechst Celanese, and

Ameritech have instituted

job pathing, challenging

assignments,

and mentoring programs to retain

key female members.

Disability

A

third trend is the increasing number of

men and women with

disabilities entering the workforce.

The

workforce

of the twenty-first century will

comprise people with a variety of

physical and mental

disabilities.

For

example, the high school

dropout rate has remained

above 4 percent throughout the

1990s, and

approximately

21 percent of the population over

age 16 have only rudimentary

reading and writing skills.

In

a

world of knowledge work, the lack of

education or an inability to learn is a

profoundly debilitating

condition.

More and more organizations

will employ physically handicapped

people, especially as the

number

of younger workers declines, creating a

great demand for labor. In

1990, the federal

Americans

with

Disabilities Act banned all forms of

discrimination on the basis of physical or

mental disability in the

hiring

and promotion process. It

also required many organizations to

modify physical plants and

office

buildings

to accommodate people with

disabilities.

The

organizational implications of the disability trend

represent both opportunity

and adjustment. The

productivity

of physically and mentally disabled

workers often surprises

managers, and training is

required

to

increase managers' awareness of this

opportunity. Employing disabled

workers, however, also means

a

need

for more comprehensive health

care, new physical workplace

layouts, new attitudes

toward working

with

the disabled and challenging

jobs that use a variety of

skills.

OD

interventions, including work

design, career planning and

development, and performance

management,

can be used to integrate the

disabled into the workforce.

For example, traditional

approaches

to

job design can simplify

work to permit physically

handicapped workers to complete an

assembly task.

Career

planning and development programs

need to focus on making disabled

workers aware of

career

opportunities.

Too often, these employees

do not know that advancement

is possible, and they are

left

feeling

frustrated. Career tracks need to be

developed for these

workers.

Performance

management interventions, including

goal setting, monitoring,

and coaching

performance,

aligned

with the workforce's characteristics are

important. At Blue Cross and Blue

Shield of Florida,

for

example,

a supervisor learned sign

language to communicate with a

deaf employee whose

productivity was

low

but whose quality of work

was high. Two other

deaf employees were

transferred to that

supervisor's

department,

and over a two-year period, the

performance of the deaf workers

improved 1,000 percent

with

no

loss in quality.

Culture

and Values

Cultural

diversity has broad organizational implications.

Different cultures represent a variety of

values,

work

ethics, and norms of correct

behavior. Not all cultures

want the same things from work,

and simple,

piecemeal

changes in specific organizational

practices will be inadequate if the

workforce is culturally

diverse.

Management practices will

have to be aligned with cultural

values and support both

career and

family

orientations. English is a second language

for many people, and jobs of

all types

(processing,

customer

contact, production, and so

on) will have to be adjusted

accordingly. Finally, the organization

will

be

expected to satisfy both extrinsic

and monetary needs, as well

as intrinsic and personal

growth needs.

Several

planned change interventions, including

employee involvement, reward

systems, and career

planning

and development, can be used to

adapt to cultural diversity. Employee

involvement practices

can

be

adapted to the needs for

participation in decision making.

People from certain

cultures, such as

Scandinavia,

are more likely to expect

and respond to high-involvement

policies; other cultures,

such as

Latin

America, view participation

with reservation. Participation in an

organization can take many

forms,

from

suggestion systems and

attitude surveys to high-involvement

work designs and

performance

management

systems. Organizations can maximize

worker productivity by basing the amount

of power and

information

workers have on cultural and

value orientations.

Reward

systems can focus on

increasing flexibility. For

example, flexible working

hours that permit

employees

to arrive at and leave work

within specified periods

enable them to meet personal

obligations

without

sacrificing organizational objectives.

Many organizations have implemented this

innovation, and

most

report that the positive benefits

outweigh the costs. Work locations

also can be varied.

Many

organizations

(e.g., Pacific Telesis,

Eddie Bauer, and Marriott)

allow workers to spend part

of their time

telecommuting

from home. Other flexible

benefits, such as floating

holidays, allow people from

different

cultures

to match important religious and

family occasions with work

schedules.

Child-care

and dependent-care assistance

also support different

lifestyles. For example, at

Stride Rite

Corporation,

the Stride Rite Intergenerational Day

Care Center houses

fifty-five children between the

ages

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

of

fifteen months and six years

as well as twenty-four elders

over sixty years old. The

center was

established

after

an organizational survey determined that 25

percent of employees provided

some sort of elder

care

and

that an additional 13 percent anticipated

doing so within five

years.

Finally,

career planning and development

programs can help workers

identify advancement

opportunities

that

are in line with their

cultural values. Some cultures

value technical skills over

hierarchical advancement;

others

see promotion as a prime indicator of

self-worth and accomplishment. By

matching programs

with

people,

job satisfaction, productivity,

and employee retention can

be improved.

Sexual

Orientation

Finally,

diversity in sexual and affectional

orientation, including gay,

lesbian, and bisexual

individuals and

couples,

increasingly is affecting the way that

organizations think about

human resources.

The

primary organizational implication of sexual

orientation diversity is discrimination. People

can have

strong

emotional reactions to sexual

orientation. When these

feelings interact with the gender,

culture, and

values

trends described above, the

likelihood of both overt and

unconscious discrimination is

high.

Interventions

aimed at this dimension of workforce diversity

are relatively new in OD and

are being

developed

as organizations encounter sexual

orientation issues in the workplace.

The most frequent

response

is education and training. This

intervention increases members'

awareness of the facts

and

decreases

the likelihood of overt discrimination.

Human resources practices having to do

with Equal

Employment

Opportunity (EEO) and fringe

benefits also can help to

address sexual orientation

parity

issues.

Some organizations have

modified their EEO

statements to address sexual

orientation. Firms

such

as

Advanced Micro Devices, Fujitsu, Ben

& Jerry's, and Dow

Chemical have communicated strongly

to

members

and outsiders that decisions

with respect to hiring,

promotion, transfer, and so on cannot

(and

will

not) be made with respect to

a person's sexual orientation. Similarly,

organizations are

increasingly

offering

domestic-partner benefit plans.

Companies such as Microsoft,

Apple, Lotus

Development

Corporation,

and Inprise Borland have

extended health-care and

other benefits to the same-sex partners

of

their

members. A 1992 Newsweek

poll found that 78 percent

of the respondents favored

extending

employee

benefits to the domestic partners of

lesbians and gay

men.

Workforce

diversity interventions are growing

rapidly in OD. A national

survey revealed that 75

percent of

firms

either have, or plan to begin, diversity

efforts. Research suggests

that diversity interventions

are

especially

prevalent in large organizations with

diversity-friendly senior management

and human resources

policies.

Although existing evidence shows

that diversity interventions are

growing in popularity, there

is

still

ambiguity about the depth of organizational commitment

to such practices and their

personal and

organizational

consequences. A great deal

more research is needed to

understand these newer

interventions

and

their outcomes.

Employee

Wellness Interventions

In

the past decade, organizations

have become increasingly

aware of the relationship between

employee

wellness

and productivity. The

estimated cost to industry from

stress-related ailments is more

than $200

billion

per year and is an

increasingly global phenomenon. In the United

Kingdom, stress and

stress-related

illness

cost industry and taxpayers

�12 billion each year.

Employee

assistance programs (EAPs)

and

stress

management interventions have

grown because organizations

are taking more responsibility

for the

welfare

of their employees. Companies

such as Johnson & Johnson,

Weyerhaeuser, Federal

Express,

Quaker

Oats, GTE, and Abbott

Laboratories are sponsoring a wide range

of fitness and wellness

programs.

In

this section, we discuss two

important wellness interventions--EAPs

and stress management. EAPs

are

primarily

reactive efforts that

identify, refer, and treat

employee problems (e.g., drug

abuse, marital

difficulties,

or depression) that affect worker

performance. Stress management,

both proactive and

reactive,

is

concerned with helping

employees alleviate or cope

with the negative consequences of

stress at work.

Employee

Assistance Programs

Forces

affecting psychological and physical

problems at the workplace are increasing.

The 1992 National

Household

Survey on Drug Abuse reported

that 66.5 percent of current

illicit drug users then 18

years or

older

were working full- or part-time.

Similarly, alcohol and other drug

use costs U.S. business an

estimated

$102

billion per year in lost

productivity, accidents, and

turnover. Britain's Royal College of

Psychiatrists

suggested

that up to 30 percent of employees in

British companies would

experience mental health

problems

and that 115 million

workdays were lost each year

as a result of depression. Other

factors, too,

have

contributed to increased problems:

altered family structures, the

growth of single-parent

households,

the

increase in divorce, greater mobility,

and changing modes of child

rearing are all fairly

recent

phenomena

that have added to the

stress experienced by employees.

These trends indicate that

an

increasing

number of employees need assistance

with personal problems, and

the research suggests

that

EAP

use increases during downsizing

and restructuring.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

EAPs

help identify, refer, and

treat workers whose personal

problems affect their performance.

Initially

started

in the 1940s to combat alcoholism,

these programs have expanded

to deal with emotional,

family,

marital,

and financial problems, and,

more recently, drug abuse. EAPs

can be either broad programs

that

address

a full range of issues or

more focused programs

dealing with specific

problems, such as drug or

alcohol

abuse.

Central

to the philosophy underlying EAPs is the

belief that although the organization

has no right to

interfere

in the private lives of its

employees, it does have a

right to impose certain

standards of work

performance

and to establish sanctions

when these are not

met. Anyone whose work

performance is

impaired

because of a personal problem is eligible

for admission into an EAP

program. Successful EAPs

have

been implemented at General Motors,

Johnson & Johnson, Motorola,

Burlington Northern

Railroad,

and

Dominion Foundries and Steel Company.

Although limited, some

research has demonstrated

that

EAPs

can positively affect

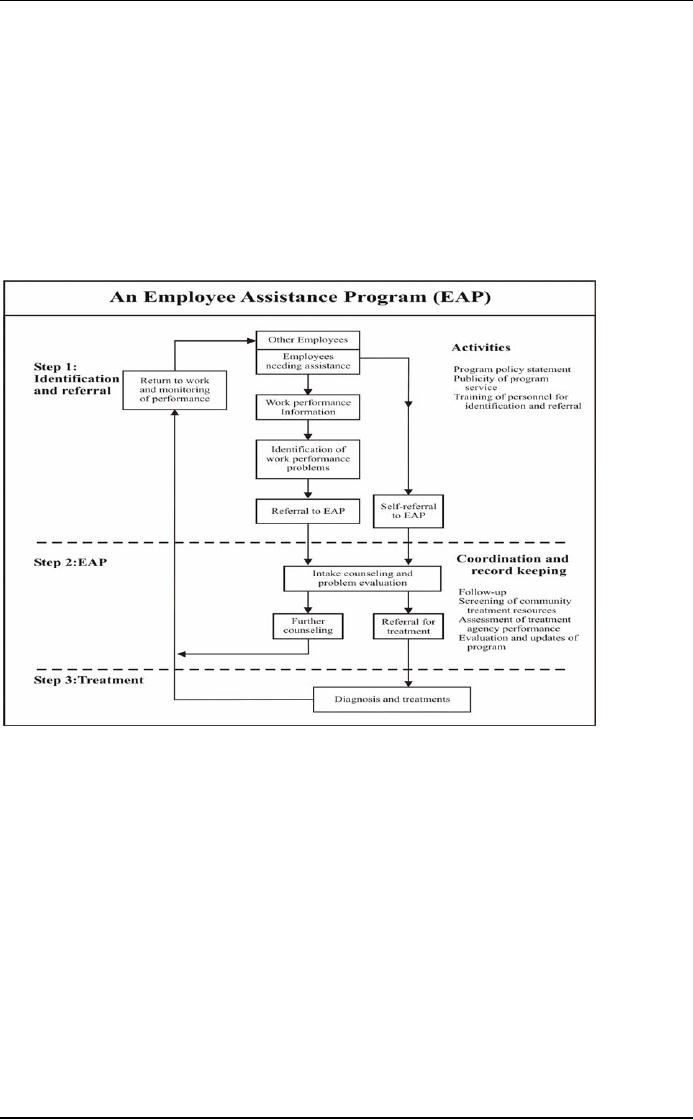

Figure

56

Absenteeism,

turnover, and job

performance. At AT&T, for example,

fifty-nine employees who

were close

to

losing their jobs were

enrolled in an EAP and

successfully returned to work. Hiring

and training

replacements

would have been much

more costly than the expense of the

EAP.

The

Employee Assistance Program

Model

Figure

56 displays the components of a typical

EAP. They include the identification and

referral of

employees

into the program, management of the EAP

process, and problem

diagnosis and treatment.

1.

Identification and referral. The

first step in an EAP is

entry into the program,

through formal or

informal

referral. In the case of formal

referrals, the process involves

identifying employees who

are having

work

performance problems and getting them to

consider entering the EAP. Identifying

these employees is

closely

related to the performance management

process. Performance records

need to be maintained and

corrective

action taken whenever performance

falls below an acceptable

standard. During action

planning

to

improve performance, managers

can point out to appraisers

the existence of support services,

such as

the

EAR. A formal referral takes

place if the performance of an employee

continues to deteriorate and the

manager

decides that EAP services

are required. An informal referral occurs

when an employee initiates

admission

to an EAP even though

performance problems may not

exist or may not have

been detected.

As

shown in Figure 56, several

organizational activities support this initial

step in the EAP process. First,

a

written

policy with clear procedures

regarding the EAP is necessary.

Second, top management and

the

human

resources department must publicly

support the EAP, and

publicity about the program should

be

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

well

distributed. Third, training and

development programs should equip supervisors to

identify and

document

performance problems effectively, to

carry out performance

improvement action planning,

and

to

develop appropriate methods for referring

employees to the EAP. Finally, the

confidentiality of

employees

using the program must be safeguarded to

gain the support of the

workforce.

2.

EAP office. The

second component of an EAP is the work

performed in the program office,

where

people

with problems are linked

with treatment resources. The

EAP office accepts an

employee into the

program,

provides problem evaluation and initial

counseling, refers the employee to

treatment resources

and

agencies, monitors the employee's

progress during treatment,

and reintegrates the employee

into the

workforce.

In some EAPs, especially in large

organizations, the actual counseling

and treatment resources

are

located in-house. In most EAPs, however,

the employee is referred to outside

agencies that contract

with

the organization to perform treatment services. In

all cases, a clear procedure

for helping the

employee

return

to the workforce is crucial and

must be managed to maintain

confidentiality.

Good

management is required for an effective

EAP. For example, the

program's relationship to disciplinary

procedures

must be clear. In some

organizations, corrective actions are

suspended if the employee

seeks

EAP

help; in others, the two processes

are not connected.

Maintaining confidential records

about

treatment

also is essential. In-house

resources have the disadvantage of

appearing to compromise this

important

program element, but they may

offer some cost savings. If

external treatment resources are

used,

care

must be taken to screen and

qualify those

resources.

3.

Treatment. The

third EAP component is the treatment of the

employee's problem. Potential

resources

include

inpatient and outpatient

care, social services, and

self-help groups. The resources tapped by

EAPs

will

vary from program to program.

Implementing

an Employee Assistance

Program

EAPs

can be flexible and

customized to fit various organizational

philosophies and employee

problems.

Practitioners

have suggested the following

seven steps in establishing an

EAP:

1.

Develop an EAP policy and

procedure.

Establish specific guidelines

concerning the EAP and

its

availability

to employees and their

families. Policies concerning

confidentiality, disciplinary

procedures,

communication,

training, and overall program

philosophy should be included. Use senior

management and

union

involvement (where appropriate) in developing the

guidelines to elicit worker

commitment.

2.

Select and train a program coordinator.

A

person should be designated by the organization as

the

EAP

coordinator. This person is responsible

for overall coordination of program

activities, such as

training,

handling

program publicity, evaluating program activities,

troubleshooting to ensure the quick

resolution of

problems,

and providing ongoing program

support.

3.

Obtain employee/union support

for the EAR Program

effectiveness demands employee or

union

support

for EAP implementation. Obtaining

that support may require

meeting with key employee or

union

representatives

to get their input in

defining significant features of the EAP,

including office

location,

staffing,

participation on an EAP advisory

committee, and employee/union

attendance at EAP training;

to

review

significant policy and/or procedural

components to ensure support; and to

share endorsements

from

other organizations where EAPs

have been implemented.

4.

Publicize

the program. Communicating

about the EAP's availability and

increasing employee

awareness

of its procedures, resources,

and benefits should be a high priority.

Both formal and

informal

referrals

to the program assume that managers

and employees are aware of

its existence. If it is not

well

publicized

or if people do not know how to

contact the program office, then

participation may be

below

expected

levels.

5.

Establish relationships with health-care

providers and insurers. All

applicable health insurance

policies

should be reviewed to determine coverage

for mental health and

chemical dependency treatment.

Although

most policies include this coverage,

reimbursement procedures often vary.

This information

needs

to be summarized for EAP

users so that all parties

are aware of potential costs

and responsibilities.

EAP

staff should be prepared to advise

employees seeking treatment about

expected insurance

coverage

and

any personal expenses

related to treatment. Potential providers of

EAP treatment services should be

interviewed,

screened, and selected, and

appropriate procedures should be developed for making

referrals

and

maintaining confidentiality.

6.

Schedule EAP training.

The

legal climate surrounding EAPs,

referrals, and employee

discipline

requires

that EAP training methods

and materials be up-to-date and

accurate. Training should include

role

plays

about handling difficult

employees as well as methods

for referring workers to the

program.

7.

Continually administer and manage the

plan. A plan

should be developed for reviewing program

effectiveness.

This typically involves

auditing procedures, measuring

system-user satisfaction,

and

determining

whether treatment options should be added or

deleted. Ongoing training of

EAP staff also

should

occur, emphasizing the changing

legal requirements of EAPs, new

counseling or treatment options,

organizational

changes that may affect program

use, and behaviors that

focus on service

quality.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Stress

Management Programs

Concern

has been growing in

organizations about managing the

dysfunction caused by stress.

Stress is

linked

to the following illnesses: hypertension,

heart attacks, diabetes,

asthma, chronic pain, allergies,

headache,

backache, various skin disorders,

cancer, immune system weakness,

and decreases in the number

of

white blood cells and

changes in their function. It

can also lead to alcoholism

and drug abuse, two

problems

that are reaching epidemic

proportions in organizations and

society. For organizations,

these

personal

effects can result in costly

health benefits, absenteeism, turnover,

and low performance. One

study

reported

that one in three workers

said they have thought about

quitting because of stress;

one in two

workers

said job stress reduced

their productivity; and one

in five workers said they

took sick leave in

the

month

preceding the survey because of

stress. Another study

estimates that each employee

who suffers

from

a stress-related illness loses an

average of sixteen days of

work per year. Finally, the

Research Triangle

Institute

estimated the annual cost to the

U.S. economy from

stress-related disorders at $187

billion. Other

estimates

are more conservative, but

they invariably run into the

billions of dollars.

Like

other human resources

management interventions, stress

management is often facilitated by

practitioners

with special skills and

knowledge--typically psychologists,

physicians, and other

health

professionals

specializing in work stress.

Recently, some OD practitioners have

gained competence in this

area,

and there has been a

growing tendency to include stress

management as part of larger OD

efforts. The

concept

of stress is best understood in terms of

a model that describes the organizational

and personal

conditions

contributing to the dysfunctional consequences of

stress. Two key types of

stress management

interventions

may be used: those aimed at

the diagnosis or awareness of stress

and its causes, and

those

directed

at changing the causes and

helping people cope with

stress.

Definition

and Model

Stress

refers to the reaction of people to their

environments. It involves both physiological

and

psychological

responses to environmental conditions,

causing people to change or adjust

their behaviors.

Stress

is generally viewed in terms of the

fit of people's needs, abilities,

and expectations with

environmental

demands, changes, and

opportunities. A good person-environment

fit results in

positive

reactions

to stress; a poor fit leads

to the negative consequences already

described. Stress is

generally

positive

when it occurs at moderate levels

and contributes to effective motivation,

innovation, and learning.

For

example, a promotion is a stressful event

that is experienced positively by

most employees. On the

other

hand, stress can be dysfunctional when it

is excessively high (or low)

or persists over a long

period of

time.

It can overpower a person's coping abilities

and cause physical and

emotional exhaustion.

For

example,

a boss who is excessively

demanding and unsupportive

can cause subordinates undue

tension,

anxiety,

and dissatisfaction. Those

factors, in turn, can lead

to withdrawal behaviors, such as

absenteeism

and

turnover; to ailments, such as

headaches and high blood

pressure; and to lowered

performance.

Situations

in which there is a poor fit

between employees and the organization

produce negative

stress

consequences.

A

tremendous amount of research has

been conducted on the causes

and consequences of work

stress.

Figure

57, a model summarizing stress

relationships, identifies specific occupational

stressors that may

result

in dysfunctional consequences. People's

individual differences determine the

extent to which the

stressors

are perceived negatively. For

example, people with strong social

support experience the

stressors

as

less stressful than those

who do not have such

support. This greater perceived stress

can lead to such

negative

consequences as anxiety, poor decision

making, increased blood pressure,

and low productivity.

Figure

57

Consequences

Subjective:

anxiety

apathy

Behavioral

Alcoholism

Drug

abuse

Accident

proneness

Cognitive

Poor

concentration

Mental

blocks

burnout

Physiological:

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Stress

and Work: A Working

model

Increased

blood pressure

Stress

Increased

heart rate

The

Appraisal

OCCUPATIONAL

STRESSORS

Organizational:

process

Lower

Physical

environment

How

the

Light,noise,temperature,polluted

air

individual

Individual:

perceives

Role

conflict role

ambiguity,

occupational

Work

overload,

lack

of

stressors

control,responsibility,work

conditions

INDIVIDUAL

Group:

DIFFERENCES

Poor

relationship

with

peers,subordinates,boss

Organizational:

Poor

structural design,

Cognitive/Affective

Politics,

no specific policy

Biological/Demographic

.

Age

Type

A or B

Hardiness

.

Gender

Social

Support

.

Occupation

Negative

Affectivity

.

Race

The

stress model shows that

almost any dimension of the organization

(e.g., working conditions,

structure,

role,

or relationships) can cause negative

stress. This suggests that

much of the material covered so

far in

this

book provides knowledge about work-related

stressors, and implies that

virtually all of the OD

interventions

included in the book can play a role in

stress management. Process consultation,

third-party

intervention,

survey feedback, inter-group

relations, structural design, employee

involvement, work

design,

goal

setting, reward systems, and

career planning and development

all can help alleviate

stressful working

conditions.

Thus, to some degree stress

management has been under

discussion throughout this

book.

Here,

the focus is on those occupational

stressors and stress-management

techniques that are unique to

the

stress

field and that have

received the most systematic

attention from stress

researchers.

Occupational

Stressors. Figure 57

identifies several organizational sources

of stress, including

structure,

role

on the job, physical environment,

and relationships. Extensive research

has been done on three

key

organizational

sources of stress: the individual

items related to work overload,

role conflict, and

role

ambiguity.

Work

overload can be a persistent source of

stress, especially among

managers and white-collar

employees

having

to process complex information and

make difficult decisions.

Quantitative overload consists of

having

too much to do in a given time period.

Qualitative overload refers to having

work that is too

difficult

for one's abilities and knowledge. A

review of the research suggests that

work overload is highly

related

to managers' needs for

achievement and so it may be

partly self-inflicted. Research

relating

workload

to stress outcomes reveals

that both too much

and too little work

can have negative

consequences.

Apparently, when the amount of work is in

balance with people's abilities

and knowledge,

stress

has a positive impact on

performance and satisfaction,

but when workload either exceeds

employees'

abilities

(overload) or fails to challenge them (underload),

people experience stress negatively. This

negative

experience

can lead to lowered self-esteem

and job dissatisfaction,

nervous symptoms,

increased

absenteeism,

and reduced participation in

organizational activities.

People's

roles at work also can be a

source of stress. A role can

be defined as the sum total of

expectations

that

the individual and significant others

have about how the person

should perform a specific job.

The

employee's

relationships with peers, supervisors,

vendors, customers, and

others can result in

diverse

expectations

about how a particular role should be performed.

The employee must be able to

integrate

these

expectations into a meaningful whole to

perform the role effectively.

Problems arise when there

is

role

ambiguity and the person does

not clearly understand what

others expect of her or him, or

when there

is

role conflict and the

employee receives contradictory

expectations that cannot be satisfied at

the same

time.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Extensive

studies of role ambiguity and

conflict suggest that both

conditions are prevalent in

organizations,

especially

among managerial jobs where

clarity often is lacking and job

demands often are

contradictory.

For

example, managerial job

descriptions typically are so

general that it is difficult to

know precisely what is

expected

on the job. Similarly, managers spend

most of their time interacting

with people from

other

departments,

and opportunities for

conflicting demands abound in these

lateral relationships.

Role

ambiguity

and conflict can cause

severe stress, resulting in increased

tension, dissatisfaction, and

withdrawal,

and reduced commitment and trust in

others. Some evidence

suggests that role ambiguity

has a

more

negative impact on managers

than does role conflict. In

terms of individual differences, people

with a

low

tolerance for ambiguity respond

more negatively to role ambiguity than

others do; introverts

and

people

who are more flexible

react more negatively to role

conflict than others

do.

Individual

Differences. Figure 57

identifies several individual

differences affecting how people respond

to

occupational

stressors: hardiness, social support,

age, education, occupation, race,

negative affectivity,

and

Type

A behavior pattern. Much research

has been devoted to the Type A

behavior pattern, which is

charac-

terized

by impatience, competitiveness, and

hostility. Type A personalities

(in contrast to Type Bs)

invest

long

hours working under tight

deadlines. They put themselves under

extreme time pressure by trying to

do

more

and more work in less

and less time. Type B

personalities, on the other hand,

are less hurried,

aggressive,

and hostile than Type As.

Extensive research shows that

Type A people are especially

prone to

stress.

For example, a longitudinal

study of thirty-five hundred

men found that Type As

had twice as much

heart

disease, five times as many

second heart attacks, and

twice as many fatal heart

attacks as did Type

Bs.

Researchers

explain Type A susceptibility to stress in

terms of an inability to deal

with uncertainty, such as

might

occur with qualitative overload

and role ambiguity. To work

rapidly and meet pressing

deadlines,

Type

As need to be in control of the situation. They do

not allocate enough time for

unforeseen

disturbances

and consequently experience

extreme tension and anxiety when

faced with unexpected

events.

Unfortunately,

the proportion of Type A managers in

organizations may be quite

large. One study

showed

that

60 percent of the managers were

clearly Type A and only 12

percent were distinctly Type

B. In

addition,

a short questionnaire measuring Type A

behaviors and given to members of

several MBA classes

and

executive programs has found

that Type As outnumber Type

Bs by about five to one. These

results are

not

totally surprising because

many organizations (and

business schools) reward

aggressive, competitive,

workaholic

behaviors. Indeed, Type A

behaviors can help managers

achieve rapid promotion in

many

companies.

Ironically, however, those same

behaviors may be detrimental to effective

performance at top

organizational

levels where tasks and

decision making require the kind of

patience, tolerance for

ambiguity,

and

attention to broad issues often

neglected by Type As.

Diagnosis

and Awareness of Stress and Its

Causes

Stress

management is directed at preventing

negative stress outcomes either by

changing the organizational

conditions

causing the stress or by enhancing

employees' abilities to cope with

them. This preventive

approach

starts from a diagnosis of the current

situation, including employees'

self-awareness of their

own

stress

and its sources. This

diagnosis provides the information needed

to develop an appropriate stress

management

program. Two methods for

diagnosing stress are the

following:

Charting

Stressors. Such

charting involves identifying organizational

and personal stressors operating in

a

particular

situation. It is guided by a conceptual model like

that shown in Figure 18.4,

and it measures

potential

stressors affecting employees negatively. Data

can be collected through

questionnaires and

interviews

about environmental and

personal stressors. Researchers at the

University of Michigan's Institute

for

Social Research have developed

standardized instruments for

measuring most of the stressors

shown in

Figure

57. It is important to obtain

perceptual measures because

people's cognitive appraisal of

the

situation

makes a stressor stressful.

Most organizational surveys measure

dimensions potentially stressful

to

employees,

such as work overload, role

conflict and ambiguity,

promotional issues, opportunities

for

participation,

managerial support, and communication. Similarly,

there are specific

instruments for

measuring

the individual differences, such as

hardiness, social support, and

Type A or B behavior pattern.

In

addition to perceptions of stressors, it

is necessary to measure stress

consequences, such as

subjective

moods,

performance, job satisfaction,

absenteeism, blood pressure,

and cholesterol level.

Various

instruments

and checklists have been

developed for obtaining people's

perceptions of negative

consequences,

and these can be

supplemented with hard measures

taken from company records,

medical

reports,

and physical examinations.

Once measures of the stressors

and consequences are obtained, the

two

sets

of data must be related to

reveal which stressors

contribute most to negative

stress in the situation

under

study. For example, a relational analysis

might show that qualitative

overload and role ambiguity

are

highly

related to employee fatigue, absenteeism,

and poor performance,

especially for Type A

employees.

This

kind of information points to

specific organizational conditions that

must be improved to

reduce

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

stress.

Moreover, it identifies the kinds of

employees who may need

special counseling and

training in stress

management.

Health

Profiling. This

method is aimed at identifying

stress symptoms so that corrective action

can be

taken.

It starts with a questionnaire

asking people for their

medical history; personal habits; current

health;

and

vital signs, such as blood

pressure, cholesterol level, and

triglyceride levels. It also may include

a

physical

examination if some of the information is

not readily available. Information

from the questionnaire

and

physical examination is then analyzed,

usually by a computer that calculates the

individual's health

profile.

This profile compares the individual's

characteristics with those of an

average person of the

same

gender,

age, and race. The

profile identifies the person's

future health prospect, typically by

placing her or

him

in a health-risk category with a known

probability of fatal disease, such as

cardiovascular risk. The

health

profile also indicates how

the health risks can be reduced by making

personal and

environmental

changes

such as dieting, exercising, or

traveling.

Alleviating

Stressors and Coping with

Stress

After

diagnosing the presence and

causes of stress, the next

step in stress management is to do

something

about

it. Interventions for

reducing negative stress

tend to fall into two

groups: those aimed at

changing the

organizational

conditions causing stress

and those directed at

helping people to cope better with

stress.

Because

stress results from the

interaction between people and the

environment, both strategies

are needed

for

effective stress management.

This

section first presents two

methods for alleviating stressful

organizational conditions: role

clarification

and

supportive relationships. These

efforts are aimed at

decreasing role ambiguity and

conflict and

improving

poor relationships, key

sources of managerial stress.

Then, two interventions

aimed at helping

people

to cope more positively with

stress are discussed: stress

inoculation training and health

and fitness

facilities.

These can help employees

alleviate stress symptoms

and prepare themselves for

handling stressful

situations.

Role

Clarification. This

involves helping employees better

understand the demands of their

work roles. A

manager's

role is embedded in a network of

relationships with other managers,

each of whom has

specific

expectations

about how the manager should perform the

role. Role clarification is a systematic

process for

revealing

others' expectations and

arriving at a consensus about the

activities constituting a particular

role.

There

are several role

clarification methods, among them

Job Expectation Technique (JET)

and Role

Analysis

Technique (RAT) and they

follow a similar strategy. First, the

people relevant to defining a

particular

role are identified (e.g.,

members of a managerial team, a

boss and subordinate, and

members of

other

departments relating to the role holder)

and brought together at a meeting,

usually in a location

away

from

the organization.

Second,

the role holder discusses

her or his perceived job

duties and responsibilities and the

other

participants

are encouraged to comment

and to agree or disagree

with the role holder's

perceptions. An

OD

practitioner may act as a

process consultant to facilitate interaction

and reduce defensiveness.

Third,

when

everyone has reached

consensus on defining the role, the role

holder is responsible for

writing a

description

of the activities that are

seen now as constituting the role. A

copy of the role description is

distributed

to all participants to ensure that they

fully understand and agree

with the role definition.

Fourth,

the

participants periodically check to see whether the

role is being performed as intended and

make

modifications

if necessary.

Supportive

Relationships. This

involves establishing trusting

and genuinely positive relationships

among

employees,

including bosses, subordinates,

and peers. Supportive relations have

been a hallmark of

organization

development and are a major part of

such interventions as team

building, intergroup

relations,

employee

involvement, work design,

goal setting, and career

planning and development.

Considerable

research

shows that supportive relationships

can buffer people from

stress. When people feel that

relevant

others

really care about what happens to them

and are willing to help, they

can cope with

stressful

conditions.

Recent

research on the boss-subordinate relationship

suggests that a supportive

boss can provide

subordinates

with a crucial defense

against stress. A study of

managers at an AT&T subsidiary

undergoing

turmoil

because of the company's corporate breakup

showed that employees who

were under considerable

stress

but felt that their

boss was supportive suffered

half as much illness,

depression, impaired sexual

performance,

and obesity as employees

reporting to an unsupportive

boss.

This

research suggests that

organizations must become

more aware of the positive

value of supportive

relationships

in helping employees cope

with stress. They may need

to build supportive, cohesive

work

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

groups

in situations that are particularly

stressful, such as introducing

new products, solving

emergency

problems,

and handling customer

complaints.

Stress

Inoculation Training. Companies

have developed programs to help

employees acquire the

skills

and

knowledge to cope more positively

with stressors. Participants

are first taught to understand

stress

warning

signals, such as difficulty in making

decisions, disruption in sleeping

and eating habits, and

greater

frequencies

of headaches and backaches.

Then they are encouraged to admit

that they are overstressed

(or

understressed)

and to develop a concrete plan

for coping with the situation. One

strategy is to develop and

use

a coping self-statement procedure.

Participants verbalize a series of

questions or statements each

time

they

experience negative stress.

The following sample

questions or statements are

addressed to the four

stages

of the stress-coping cycle:

�

Preparation (What am I going to do about

these stressors?)

�

Confrontation (I must relax

and stay in control.)

�

Coping (I must focus on the

present set of

stressors.)

�

Self-reinforcement (I handled it well.)

Stress

inoculation training is aimed at

helping employees cope with

stress rather than at changing

the

stressors

themselves. Its major value is

sensitizing people to the presence of

stress and preparing them to

take

personal action. Self-appraisal and

self-regulation of stress can free people

from total reliance

on

others

for stress management. Given

the multitude of organizational conditions

that can cause stress,

such

self-control

is a valuable adjunct to interventions

aimed at changing the conditions

themselves.

Health

Facilities. A

growing number of organizations are

providing facilities for helping

employees cope

with

stress. Elaborate exercise facilities are

maintained by such firms as Xerox,

Weyerhaeuser, and

PepsiCo.

Similarly,

more than five hundred

companies (e.g., Exxon,

Mobil, and Chase Manhattan

Bank) operate

corporate

cardiovascular fitness

programs.

In

addition to exercise facilities, some

companies, such as McDonald's

and Equitable Life

Assurance

Society,

provide biofeedback facilities in which

managers take relaxation breaks

using biofeedback devices

to

monitor respiration and heart

rate. Feedback of such data

helps managers lower their

respiration and

heart

rates. Some companies

provide time for employees to

meditate, and other firms

have stay-well

programs

that encourage healthy diets

and lifestyles.

Table of Contents:

- The Challenge for Organizations:The Growth and Relevance of OD

- OD: A Unique Change Strategy:OD consultants utilize a behavioral science base

- What an “ideal” effective, healthy organization would look like?:

- The Evolution of OD:Laboratory Training, Likert Scale, Scoring and analysis,

- The Evolution of OD:Participative Management, Quality of Work Life, Strategic Change

- The Organization Culture:Adjustment to Cultural Norms, Psychological Contracts

- The Nature of Planned Change:Lewin’s Change Model, Case Example: British Airways

- Action Research Model:Termination of the OD Effort, Phases not Steps

- General Model of Planned Change:Entering and Contracting, Magnitude of Change

- The Organization Development Practitioner:External and Internal Practitioners

- Creating a Climate for Change:The Stabilizer Style, The Analyzer Style

- OD Practitioner Skills and Activities:Consultant’s Abilities, Marginality

- Professional Values:Professional Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, Technical Ineptness

- Entering and Contracting:Clarifying the Organizational Issue, Selecting an OD Practitioner

- Diagnosing Organizations:The Process, The Performance Gap, The Interview Data

- Organization as Open Systems:Equifinality, Diagnosing Organizational Systems

- Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Methods for Collecting Data, Observations

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Sampling, The Analysis of Data

- Designing Interventions:Readiness for Change, Techno-structural Interventions

- Leading and Managing Change:Motivating Change, The Life Cycle of Resistance to Change

- Leading and managing change:Describing the Core Ideology, Commitment Planning

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Measurement

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Research Design

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Group Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Leadership and Authority, Group Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Third-Party Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Building, Team Building Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Management Styles

- Organization Process Approaches:Application Stages, Microcosm Groups

- Restructuring Organizations:Structural Design, Process-Based Structures

- Restructuring Organizations:Downsizing, Application Stages, Reengineering

- Employee Involvement:Parallel Structures, Multiple-level committees

- Employee Involvement:Quality Circles, Total Quality Management

- Work Design:The Engineering Approach, Individual Differences, Vertical Loading

- Performance Management:Goal Setting, Management by Objectives, Criticism of MBO

- Developing and Assisting Members:Career Stages, Career Planning, Job Pathing

- Developing and Assisting Members:Culture and Values, Employee Assistance Programs

- Organization and Environment Relationships:Environmental Dimensions, Administrative Responses

- Organization Transformation:Sharing the Vision, Three kinds of Interventions

- The Behavioral Approach:The Deep Assumptions Approach

- Seven Practices of Successful Organizations:Training, Sharing Information