|

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

40

Developing

and Assisting Members

This

lecture presents three human

resources management interventions

concerned with developing

and

assisting

the well-being of organization members. First,

organizations have had to

adapt their career

planning

and development processes to a variety of

trends. For example, people

have different needs

and

concerns

as they progress through their

career stages; technological changes

have altered organizational

structures

and systems dramatically;

and global competition has

forced organizations to redefine how

work

gets

done. These processes and

concerns have forced individuals

and organizations to redefine the

social

contract

that binds them together. Career planning

and development interventions can

help deal effectively

with

these issues. Second,

increasing workforce diversity provides an

especially challenging environment

for

human

resources management. The

mix of genders, ages, value

orientations, thinking styles, and

ethnic

backgrounds

represented in the modern workforce is

increasingly varied. Management's

perspectives,

strategic

responses, and implementation

approaches can help address

pressures posed by this

diversity.

Finally,

wellness interventions, such as

employee assistance and

stress management programs,

are

addressing

several important social

trends, such as fitness and

health consciousness, drug and

alcohol

abuse,

and work-life

balance.

Career

Planning and Development

Interventions:

Career

planning and development have

been receiving increased attention in

organizations. Growing

numbers

of managers and professional staff

are seeking more control

over their work lives.

As

organizations

downsize and restructure,

there is less trust in the organization to

provide job security.

Employees

are not willing to have

their careers "just happen"

and are taking an active

role in planning and

managing

them. This is particularly true for

women, mid-career employees,

and college recruits, who

are

increasingly

asking for career planning

assistance. On the other hand,

organizations are becoming

more and

more

reliant on their "intellectual capital."

Providing career planning

and development opportunities

for

organization

members helps to recruit and retain

skilled and knowledgeable workers.

Many talented job

candidates,

especially minorities and

women, are showing a

preference for employers who

offer career

advancement

opportunities.

Many

organizations--General Electric, Xerox,

Intel, Ciba-Geigy, Cisco Systems, Quaker

Oats, and Novotel

UK,

among others--have adopted career

planning and development programs.

These programs have

attempted

to improve the quality of work

life for managers and

professionals, to improve

their

performance,

to increase employee retention,

and to respond to equal employment

and affirmative action

legislation.

Companies have discovered

that organizational growth and

effectiveness require career

development

programs to ensure that

needed talent will be available.

Competent managers are often

the

scarcest

resource. Many companies

also have experienced the

high costs of turnover among

recent college

graduates,

including MBAs, which can

reach 50 percent after five

years. Career planning and

development

help

attract and hold such

highly talented employees and

can increase the chances

that their skills

and

knowledge

will be used.

Organizations

are discovering that the career

development needs of women and

minorities often require

special

programs and the use of

nontraditional methods, such as

integrated systems for

recruitment,

placement,

and development. Similarly, age-discrimination laws

have led many organizations to

set up

career

programs aimed at older

managers and professionals.

Thus, career planning and

development are

increasingly

being applied to people at different ages

and stages of development--from

new recruits to

those

nearing retirement age.

Finally,

career planning and development

interventions increasingly have

been used in cases of

"career halt"

where

layoffs and job losses have

resulted from organization decline,

downsizing, reengineering, and

restructuring.

These abrupt halts to career

progress can have severe

human consequences, and

human

resources

practices have been developed

for helping members cope

with these problems.

Career

planning is concerned with

individuals choosing occupations,

organizations, and positions at

each

stage

of their careers. Career development

involves helping employees attain

career objectives.

Although

both

of these interventions generally

are aimed at managerial and

professional employees, a

growing

number

of programs are including lower-level

employees, particularly those in

white-collar jobs.

Career

Stages:

A

career consists of a sequence of

work-related positions occupied by a person

during the course of a

lifetime.

Traditionally, careers were judged in

terms of advancement and

promotion upward in the

organizational

hierarchy. Today, they are defined in

more holistic ways to include a

person's attitudes

and

experiences.

For example, a person can

remain in the same job, acquiring

and developing new skills,

and

have

a successful career without

ever getting promoted. Similarly, people

may move horizontally through

a

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

series

of jobs in different functional

areas of the firm. Although they

may not be promoted upward in

the

hierarchy,

their broadened job

experiences constitute a successful

career.

Considerable

research has been devoted to

understanding how aging and

experience affect people's

careers.

This

research has drawn on the extensive

work done on adult growth

and development and has

adapted

that

developmental perspective to work

experience. Results suggest

that employees progress

through at

least

four distinct career stages as they

mature and gain experience.

Each stage has unique

concerns, needs,

and

challenges.

1.

The establishment stage (ages

21-26 years). This

phase is the outset of a career when

people are

generally

uncertain about their competence and

potential. They are

dependent on others, especially

bosses

and

more experienced employees,

for guidance, support, and

feedback. At this stage, people are

making

initial

choices about committing themselves to a

specific career, organization, and

job. They are

exploring

possibilities

while learning about their own

capabilities.

2. The

advancement stage (ages

26-40 years). During

this phase, employees become

independent

contributors

who are concerned with

achieving and advancing in

their chosen careers. They

have typically

learned

to perform autonomously and need

less guidance from bosses

and closer ties with

colleagues. This

settling-down

period also is characterized by

attempts to clarify the range of

long-term career

options.

3.

The maintenance stage (ages 40-60

years).

This phase involves leveling

off and holding on to

career

successes.

Many people at this stage have

achieved their greatest

advancements and are now

concerned

with

helping less-experienced subordinates.

For those who are

dissatisfied with their

career progress, this

period

can be conflictual and

depressing, as characterized by the term

"midlife crisis." People

often

reappraise

their circumstances, search

for alternatives, and redirect

their career efforts.

Success in these

endeavors

can lead to com inning

growth, whereas failure can

lead to early

decline.

4.

The withdrawal stage (ages 60

years and above).

This final stage is

concerned with leaving a

career.

It

involves letting go of organizational

attachments and getting ready

for greater leisure time and

retirement.

The

employee's major contributions are

imparting knowledge and experience to

others. For those

people

who

are generally satisfied with

their careers, this period

can result in feelings of

fulfillment and a

willingness

to leave the career

behind.

The

different career stages

represent a broad developmental perspective on

people's jobs. They

provide

insight

about the personal and career

issues that people are

likely to face at different

career phases. These

issues

can be potential sources of

stress. Employees are likely

to go through the phases at different

rates,

and

to experience personal and

career issues differently at

each stage. For example,

one person may

experience

the maintenance stage as a positive

opportunity to develop less-experienced

employees; another

person

may experience the maintenance

stage as a stressful leveling off of

career success.

Career

Planning:

Career

planning involves setting

individual career objectives. It is

highly personalized and

generally includes

assessing

one's interests, capabilities,

values, and goals; examining alternative

careers; making decisions

that

may

affect the current job; and planning

how to progress in the desired

direction. This process results

in

people

choosing occupations, organizations,

and jobs. It determines, for

example, whether individuals

will

accept

or decline promotions and

transfers and whether they will

stay or leave the company

for another job

or

for retirement.

The

four career stages can be

used to make career planning

more effective. Table 18.1

shows the different

career

stages and the career

planning issues relevant at each

phase. Applying the table to a

particular

employee

involves first diagnosing the person's

existing career stage--establishment,

advancement,

maintenance,

or withdrawal. Next, available career

planning resources are used

to help the employee

ad-

dress

pertinent issues. Career

planning programs include some or

all of the following

resources:

�

Communication

about career opportunities and

resources available to employees

within the

organization

�

Workshops

to encourage employees to assess

their interests, abilities, and

job situations and to

formulate

career development plans

�

Career

counseling by managers or human

resources personnel

�

Self-development

materials, such as books, videotapes,

and other media, directed

toward

identifying

life and career

issues

�

Assessment

programs that provide

various tests of vocational interests,

aptitudes, and abilities

relevant

to setting career

goals.

Application

9 describes the career planning

resources available at Pacific Bell. It

provides an example of the

range

of resources that can be

provided and how these

programs can be implemented

flexibly.

According

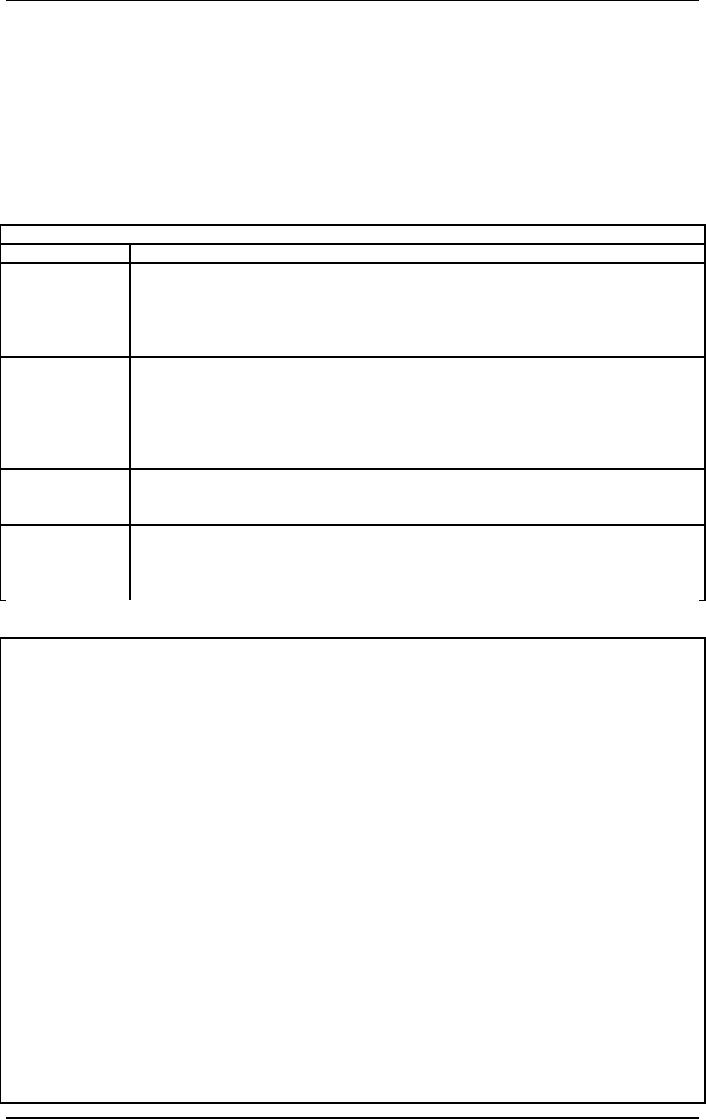

to Table 19, employees who

are just becoming

established in careers can be

stressed by concerns

for

identifying alternatives, assessing

their interests and

capabilities, learning how to perform

effectively,

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

and

finding out how they are

doing. At this stage, the company should

provide considerable

communication

and counseling about available

career paths and the skills

and abilities needed to progress

in

them.

Workshops, self-development materials,

and assessment techniques should be

aimed at helping

employees

assess their interests,

aptitudes, and capabilities

and at linking that

information to possible

careers

and jobs. Considerable

attention should be directed to giving

employees continual feedback

about

job

performance and to counseling them about

how to improve it. The

supervisor-subordinate relationship

is

especially important for

these feedback and development

activities.

People

at the advancement stage are mainly

concerned with getting ahead, discovering

long-term career

options,

and integrating career choices,

such as transfers or promotions,

with their personal lives.

Here, the

company

should provide employees with

communication and counseling about

challenging assignments

and

Table

19

Career

Stages and Career Planning

Issues

Career

Stage

Career-Planning

Issues

Establishment

What

are alternative occupations,

organizations and

jobs?

What

are my interests and

capabilities?

How

do I get the work

accomplished?

Am

I performing as expected?

Am

I developing he necessary skills

for advancement?

Advancement

Am

I advancing as expected?

How

can I advance more

effectively?

What

long-term options are

available?

How

do I get more exposure and

visibility?

How

do I develop more effective peer

relationship?

How

do I better integrate career choices

with my personal life?

Maintenance

How

do I help others become

established and

advance?

Should

I reassess myself and my

career?

Should

I redirect my action?

Withdrawal

What

are my interests outside of

work?

What

postretirement work options are

available to me?

How

can I be financially

secure?

How

can I continue to help

others?

Application

9: Career Planning Centers at

Pacific Bell

Pacific

Bell, a Pacific Telesis company, provides

local telephone products and services to

residential and

business

customers throughout California.

The company operates ten

career centers, each managed

by an

on-site

career development specialist with at

least ten months of intensive on-the-job

training. In addition,

the

company operates two mobile

vans that serve the career

needs of employees in outlying

areas.

Employees

come to the center on their

own or may be referred by their

managers or a medical health

services

counselor. Their visits are

completely confidential.

Each

center has a reference

library of print, audio, and

video resources on career

planning, retirement

planning,

job titles, and corporate culture.

Employees have access to the

company's job posting

systems

and

computerized, self-guided career-life

planning programs. All of the

center's resources are

linked to the

corporate

business plan. The center's staff

also provides workshops on resume

writing, interviewing,

group

interpretation

of career assessments, and

career planning.

An

employee can make an

appointment with the career development

specialist who will help

him or her

examine

personal skills, interests, abilities,

and values and identify

appropriate career choices.

The

counseling

process helps the worker

answer the questions, "Who am 1?

How am I seen? Where do I

want

to

go? How do I get

there?"

The

specialist will help

employees research career

options within the company or

outside, if necessary,

and

to

appraise their skills and

abilities realistically against the job

requirements. Personal issues affecting

career

options

are considered and incorporated

into each employee's

individualized plan. Specialists also

provide

ongoing

support while employees are

making job changes and

transitions.

Brian

Cowgill, the career counselor

who provides clinical supervision to the

northern California

centers,

says

that the centers were

created in response to Pacific

Bell's strategic changes as

well as to changes in the

work

environment and employees'

values and needs. "Pacific

Bell has changed its

corporate mission to be

more

focused on the customer," says Cowgill.

"As a result, job

descriptions and job duties

have changed

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

for

many employees. They are

challenged to examine their

interests and abilities in order to

keep up with

the

changing work

environment."

In

addition, employee values

have shifted. For example, younger

employees are challenging

old

assumptions

about work and are feeling the

need to explore all the options open to

them. Employee loyalty

and

commitment are low, especially

among the newly hired who

have highly sought skills

and knowledge.

A

flattening of organizational structures

leaves these employees with

fewer opportunities for upward

ad-

vancement,

and they are actively making themselves

available to the highest bidder.

The career centers

enable

these employees to discover

how best to use their

skills and abilities.

possibilities

for more exposure and

demonstration of skills. It should help

clarify the range of

possible

long-term

career options and provide

members with some idea about

where they stand in achieving

them.

Workshops,

developmental materials, and assessment

methods should be aimed at helping

employees

develop

wider collegial relationships, join with

effective mentors and sponsors,

and develop more creativity

and

innovation. These activities also should

help people assess both

career and personal life

spheres and

integrate

them more successfully.

At

the maintenance stage, individuals

are concerned with helping

newer employees become

established and

grow

in their careers. This phase

also may involve a

reassessment of self and

career and a possible

redirection

to something more rewarding.

The firm should provide

individuals with communications

about

the

broader organization and how their

roles fit into it.

Workshops, developmental materials,

counseling,

and

assessment techniques should be aimed at

helping employees to assess

and develop skills in order

to

train

and coach others. For

those experiencing a midlife

crisis, career planning activities should

be directed

at

helping them to reassess their

circumstances and to develop in new

directions. Midlife crises generally

are

caused

by perceived threats to people's

career or family identities. Career

planning should help people

deal

effectively

with identity issues,

especially in the context of an ongoing

career. This may include

workshops

and

close interpersonal counseling to help

people confront identity issues

and reorient their thinking

about

themselves

in relation to work and

family. These activities also

might help employees deal

with the

emotions

evoked by a midlife crisis and develop

the skills and confidence to

try something new.

Employees

who are at the withdrawal stage

can experience stress about

disengaging from work

and

establishing

a secure leisure life. Here, the

company should provide communications

and counseling about

options

for postretirement work and financial

security, and it should convey the

message that the

employee's

experience in the organization is still

valued. Retirement planning

workshops and materials

can

help

employees gain the skills

and information necessary to

make a successful transition

from work to non

work

life. They can prepare

people to shift their attention

away from the organization to other

interests and

activities.

Effective

career planning and development

requires a comprehensive program integrating

both corporate

business

objectives and employee

career needs. This is accomplished

through human resources

planning

aimed

at developing and maintaining a workforce

to meet business objectives. It

includes recruiting

new

talent,

matching people to jobs, helping them

develop careers and perform

effectively, and preparing them

for

satisfactory retirement. Career planning

activities feed into and

support career development and

human

resources

planning activities.

Career

Development:

Career

development helps individuals achieve

their career objectives. It

follows closely from

career

planning

and includes organizational practices

that help employees implement

those plans. These

may

include

skill training, performance

feedback and coaching, planned

job rotation, mentoring, and

continuing

education.

Career

development can be integrated with

people's career needs by

linking it to different career

stages. As

described

earlier, employees progress through

distinct career stages, each

with unique issues relevant to

career

planning: establishment, advancement,

maintenance, arid withdrawal. Career

development

interventions

help members implement these

plans. Table 20 identifies

career development interventions,

lists

the career stages to which they

are most relevant, and

defines their key purposes

and intended

outcomes.

It shows that career development

practices may apply to one or

more career stages.

Performance

feedback

and coaching, for example,

are relevant to both the establishment

and advancement stages.

Career

development

interventions also can serve

a variety of purposes, such as helping

members identify a

career

path

or providing feedback on career

progress and work

effectiveness. They can

contribute to different

organizational

outcomes such as lowering

turnover and costs and

enhancing member

satisfaction.

Career

development interventions traditionally

have been applied to younger employees

who have a longer

time

period to contribute to the firm

than do older members.

Managers often stereotype

older employees

as

being less

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

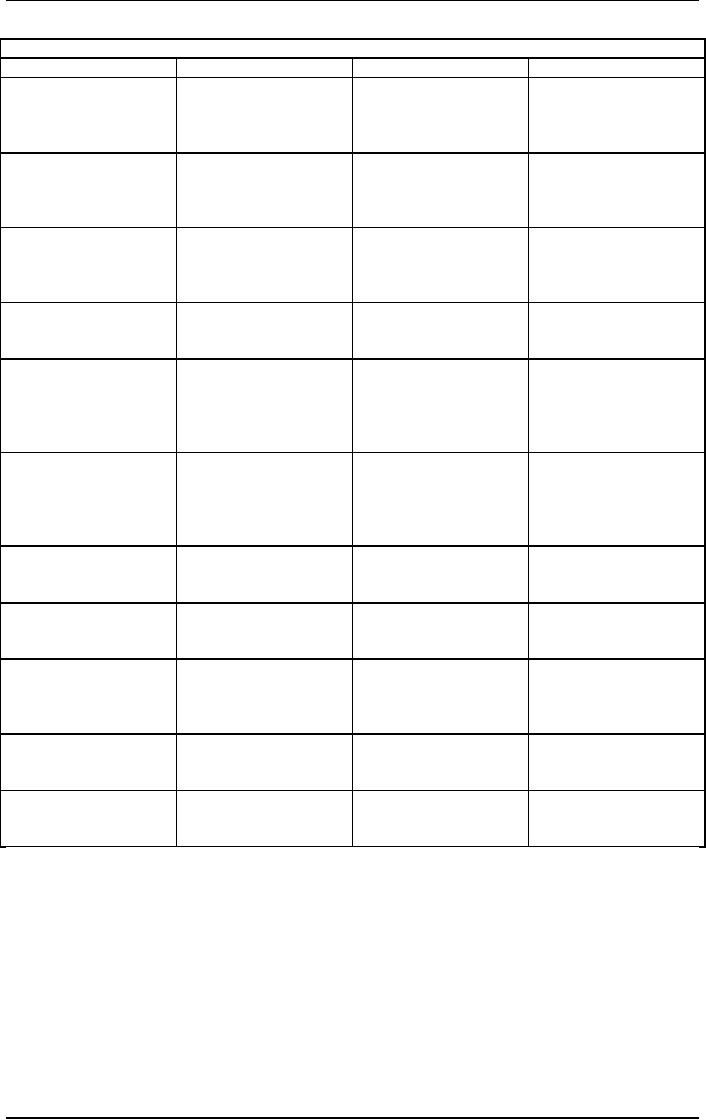

Table

20

Career

Development Interventions

Intervention

Career

Stage

Purpose

Intended

outcomes

Realistic

job preview

Establishment

to

provide members

Reduce

turnover

Advancement

with

an

accurate

Reduce

training costs

expectation

of work

Increase

commitment

requirements

Increase

job satisfaction

Job

pathing

Establishment

To

provide members

Reduce

turnover

Advancement

with

a sequence of work

Build

organizational

assignments

leading to a

knowledge

career

objective

Performance

feedback

Establishment

To

provide members

Increase

productivity

and

coaching

Advancement

with

knowledge about

Increase

job satisfaction

their

career progress and

Monitor

human

work

effectiveness

resources

development

Assessment

centers

Establishment

To

select and develop

Increase

person-job fit

Advancement

members

for managerial

Identify

high-potential

and

technical jobs

candidates

Mentoring

Establishment

To

link

a

less-

Increase

job satisfaction

Advancement

experienced

member

Increase

member

Maintenance

with

a more-experienced

motivation

member

for member

development

Developmental

training

Establishment

To

provide education

Increase

organizational

Advancement

and

training

capability

Maintenance

opportunities

that help

members

achieve career

goals

Work-life

balance

Establishment

To

help

members

Improve

quality of life

planning

Advancement

balance

work

and

Increase

productivity

Maintenance

personal

goals

Job

rotation

and

Advancement

To

provide members

Increase

job satisfaction

challenging

assignments Maintenance

with

interesting work

Maintain

member

motivation

Dual-career

Advancement

To

assist members with Attract

and retain high-

accommodations

Maintenance

significant

others to find quality

members

satisfying

work

Increase job

satisfaction

assignments

Consultative

roles

Maintenance

To

help members fill

Increase

problem-

Withdrawal

productive

roles later in solving capacity

their

careers

Increase

job satisfaction

Phased

retirement

Withdrawal

To

assist members in Increase

job satisfaction

moving

into retirement

Lower

stress during

transition

creative,

alert, and productive than

younger workers and consequently

provide them with less

career

development

support.10 Similarly, Table 20 suggests

that the OD field has been

relatively lax in developing

methods

for helping older members

cope with the withdrawal stage

because only two of the

eleven

interventions

presented there apply to the withdrawal

stage--consultative roles and phased

retirement. This

relative

neglect can be expected to

change in the near future; however, as

the U.S. workforce continues

to

grey.

To sustain a highly committed and

motivated workforce, organizations

increasingly will have

to

address

the career needs of older

employees. They will have to

recognize and reward the

contributions that

older

workers make to the company.

Workforce diversity interventions,

discussed later in this chapter,

are a

positive

step in that

direction.

Realistic

Job Preview:

This

intervention provides organization members

with realistic expectations

about the job during

the

recruitment

process. It provides recruits with

information about whether the job is

likely to be consistent

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

with

their needs and career

plans. Such knowledge is especially

useful during the establishment

stage, when

people

are most in need of

realistic information about

organizations and jobs. It

also can help

employees

during

the advancement stage, when job

changes are likely to occur

because of promotion.

Research

suggests that people may develop

unrealistic expectations about the organization

and job. They

can

suffer from "reality shock" when

those expectations are not

fulfilled and may leave the

organization or

stay

and become disgruntled and

unmotivated. To overcome these

problems, organizations such as

Texas

Instruments,

Prudential Insurance, and Johnson &

Johnson provide new recruits

with information about

both

the positive and negative

aspects of the company and the

job. They furnish recruits

with booklets,

talks,

and site visits showing what

organizational life is really like.

Such information reduces the

chances

that

employees will develop unrealistic

job expectations and become

disgruntled and leave the

company.

This

can lead to reduced turnover

and training costs, and

increased organizational commitment and

job

satisfaction.

Job

Pathing:

This

intervention provides members with a

carefully developed sequence of work

assignments leading to a

career

objective, although the notion of a job

path in the new economy is being

challenged. It helps

members

in the establishment and advancement

stages of their careers. Job

pathing helps

employees

develop

skills, knowledge, and competencies by

performing jobs that require

new skills and

abilities.

Research

suggests that employees who

receive challenging job

assignments early in their

careers do better in

later

jobs. Career pathing allows

for a gradual stretching of

people's talents by moving them

through

selected

jobs of increasing challenge

and responsibility. As a person

gains experience and

demonstrates

competence

in the job, she or he moves to another

job with more advanced

skills and knowledge.

Performing

well on one job increases

the chance of being assigned to a more

demanding job.

The

keys to effective job pathing

are to identify the skills an

employee needs for a certain

target job and

then

to lay out a sequence of

interim jobs that will

provide those experiences.

The interim jobs

should

provide

enough challenge to stretch a person's

learning capacity without overwhelming the

employee or

withholding

the target job too long.

Some banks, for example,

have used job pathing to

provide employees

with

a specific series of jobs for learning

how to become a branch

manager. In one Los Angeles bank,

the

jobs

in the path include teller, loan officer, credit

manager, and commercial loan

manager. Job pathing

reduces

turnover by offering opportunities

for advancement. It also can

build organizational knowledge. As

employees

advance along career paths, they

gain skills and experience

to resolve organizational

problems,

to

assist in large-scale organization

change, and to transfer

their accumulated knowledge to new

members.

Performance

Feedback and Coaching:

One

of the most effective interventions

during the establishment and

advancement phases

includes

feedback

about job performance and

coaching to improve performance.

Employees need

continual

feedback

about goal achievement as well as

necessary support and

coaching to improve their

performances.

Feedback

and coaching are particularly relevant

when employees are

establishing careers. They

have

concerns

about how to perform the

work, whether they are performing up to

expectations, and whether

they

are gaining the necessary skills

for advancement. A manager

can facilitate career establishment

by

providing

feedback on performance, coaching,

and on-the-job training.

These activities can

help

Application

10: Realistic job Preview at

Nissan

James

Mandelker had two minutes to

grab fifty-five nuts, bolts,

and washers; assemble them in

groups of

five;

and attach them in order of

size to a metal rack. But he

fumbled nervously with several

pieces and

finished

the task seconds after his

allotted time. "I've got to

get a little better at this, don't

I?" he frowned,

as

he pulled the last of the fasteners

out of a grimy plastic tray.

His tester, Gloria Macaluso,

encouraged

him:

"You're close. For the first

night, you're probably doing a

little better than

normal."

James

is trying to get a job at the

Nissan Motor Manufacturing

Corporation plant in Smyrna,

Tennessee.

The

thirty-one-year-old department-store

employee will be devoting

seventy hours worth of his

nights and

weekends

during the next few months doing

similar exercises. James and

about 270 other job seekers

are

participating

in Nissan's preemployment program. In

exchange for a shot at

highly paid assembly-line

jobs

and

Nissan's promise not to

inform their employers,

these moonlighters will work as

many as 360 hours

without

being paid. They will be tested and

instructed in employment fundamentals by the

Japanese

automaker.

"We hope the process makes it plain to

people what the job is," says Thomas P.

Groom,

Nissan's

manager of employment. "It's an

indoctrination process as well as a

screening tool."

Not

all participants are fully

satisfied with the program. One

candidate who works as a machine

adjuster at

an

envelope factory says the long pre-employment

period "worries you, because

you get your hopes

up."

And

some candidates bemoan the

lack of pay for their time.

But many participants feel that the

training and

experience

outweigh the unpaid work required to

get hired. For one thing,

they get a shot at some of

the

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

best-paying

jobs in the state. If they are not hired,

they can take elsewhere the

skills they have learned

there.

Loraine

Olsen, a press operator who went

through the program, said, "It

gave me a chance to see

what

Nissan

expected of me without their having to

make a commitment to me or me to

them."

Employees

get the job done while

meeting their career development

needs. Companies such as

Intel and

Monsanto,

for example, use performance

feedback and coaching for

employee career development. They

separate

the career development aspect of

performance appraisal from the

salary review component, thus

ensuring

that employees' career needs

receive as much attention as

salary issues. Feedback and

coaching

interventions

can increase employee

performance and satisfaction,

and provide a systematic way

to monitor

the

development of human resources in the

firm.

Assessment

Centers:

This

intervention was traditionally

designed to help organizations

select and develop employees

with high

potential

for managerial jobs. More

recently, assessment centers have

been extended to career

development

and

to selection of people to fit new

work designs, such as

self-managing teams. When

used to evaluate

managerial

capability, assessment centers typically

process twelve to fifteen people at a time

and require

them

to spend two to three days

on site. Participants are given a

comprehensive interview, take

several tests

of

mental ability and knowledge,

and participate in individual and

group exercises intended to

simulate

managerial

work. An assessment team

consisting of experienced managers

and human resources

specialists

observes

the behaviors and performance of

each candidate. This team

arrives at an overall assessment

of

each

participant's managerial potential,

including a rating on several

items believed to be relevant to

managerial

success in the organization, and pass the

results to management for

use in making promotion

decisions.

Assessment

centers have been applied to

career development as well, where the

emphasis is on feedback of

results

to participants. Trained staff helps

participants hear and understand

feedback about their strong

and

weak

points. They help participants become

clearer about career

advancement and identify

training experi-

ences

and job assignments to

promote that progress. When

used for developmental purposes,

assessment

centers

can provide employees with

the support and direction

needed for career development. They

can

demonstrate

that the company is a partner rather than

an adversary in that process.

Although assessment

centers

can help people's careers at

all stages of development, they seem

particularly useful at the

advancement

stage, when employees need to

assess their talents and

capabilities in light of long-term

career

commitments.

Research suggests that

assessment centers can

promote career advancement to the

extent

that

participants are willing to work on the

center's recommendations for development.

When participants

develop

themselves in such areas as clarity about

career motivation and

ability to work with others,

their

probability

of promotion increases.

Assessment

centers are being used

increasingly to select members

for new work designs.

They provide

comprehensive

information about how

recruits are likely to

perform in such settings,

which can increase

the

fit between the employee and

the job and consequently

lead to higher levels of employee

performance

and

satisfaction. Application 18.4

shows how such centers

can be used for selection

purposes in a team-

based

organization. It illustrates how this

intervention can help

organizations select the right

people,

shorten

training cycles, and improve

productivity.

Mentoring:

One

of the most useful ways to

help employees advance in

their careers is sponsorship.

This involves

establishing

a close link between a

manager or someone more

experienced and another

organization

member

who is less experienced.

Mentoring is a powerful intervention

that assists members in

the

establishment,

advancement, and maintenance

stages of their careers. For

those in the establishment

stage,

a

sponsor or mentor takes a

personal interest in the employee's

career and guides and

sponsors it. This

ensures

that a person's hard work

and skill translate into

actual opportunities for

promotion and

advancement.

For older employees in the

maintenance stage, mentoring provides

opportunities to share

knowledge

and experience with others

who are less experienced.

Older managers may mentor

younger

employees

who are in the establishment

and advancement career

stages. Mentors do not have

to be the

direct

supervisors of the younger employees but

can be hierarchically or functionally distant

from them.

Other

mentoring opportunities include

temporarily assigning veteran

managers to newer managers to

help

them

gain managerial skills and

knowledge. For example, during the

startup of a new manufacturing

plant,

the

plant manager, who was in

the advancement career stage,

was assisted by a veteran

with years of

experience

in manufacturing management. The veteran

was temporarily located at the

new plant to help the

plant

manager develop the skills and knowledge

to get the plant operating and to

manage it. Once a

month,

a

consultant helped the two managers

examine their relationship and

set action plans for

improving the

mentoring

process.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Several

of Boeing's divisions have well-developed

mentoring processes. High-potential

members are

identified

and paired with a corporate

manager who volunteers to be a mentor.

The mentor helps the

employee

gain the skills, experience,

and visibility necessary for

advancement in the company.

Senior

executives

strongly support the mentoring program and

believe that it is necessary

for managerial

success.

They

believe that "mentoring improves the

pool of talent for management

and technical jobs and

helps to

shape

future leaders. It is also an effective

vehicle for moving knowledge

through the organization from the

people

who have the most

experience.

Application

11: Assessment Center for

Employee Selection at

Hamilton-Standard

The

Hamilton-Standard Commercial Aircraft

Electronics Division of United Technologies

manufactures

environmental

and jet engine control

systems for commercial

aerospace applications. In 1991, the

division

moved

to Colorado Springs when it was

awarded a contract on the Boeing 777. To

achieve demanding

standards

of quality, cost, and time,

Hamilton-Standard used a high-involvement

work design. This

design

included

a relatively flat hierarchy and

self-managed work teams

composed of members who were

certified

in

a variety of technical, business, and

interpersonal skills. The teams

were highly flexible and

able to follow

the

product through all areas of

production. Although a number of workers,

staff members, and

managers

moved

with the division to Colorado

Springs, the increased scale of

operations needed for the Boeing

contract

required hiring and training a

large number of new team

members over the next

eighteen to

twenty-four

months--a daunting task in a

new geographic

location.

To

find the right people for the

team-based structure, Hamilton-Standard

created an assessment center.

It

was

run by division personnel,

including existing team members, staff,

and managers, who

underwent

extensive

training to learn how to review

resumes, conduct interviews, and assess

experiential exercises.

The

assessment center included a number of activities

aimed at evaluating the ability of job

applicants to

work

in teams, make decisions,

and learn new

skills.

Preliminary

assessment began with an

information session for

candidates who submitted resumes to

the

division.

Groups of about 150 applicants

engaged in an interactive, two-hour

meeting that addressed

the

firm's

products and expectations for

new employees. Candidates

also discovered what they could

expect

from

Hamilton-Standard in terms of

compensation, benefits, work

environment, and developmental

opportunities.

At the end of the session, participants

were invited to complete

formal job

applications,

which

subsequently were reviewed to

identify high-potential candidates

who would be asked to

participate

in

the center's evaluation process.

The

assessment center was

designed to evaluate sixty-five to

seventy candidates in a single

day--typically a

Saturday,

to accommodate recruits who

were employed elsewhere. In the week

before they attended the

center,

candidates completed a battery of tests

that measured generic work

skills, social competence,

and

mathematical

knowledge. These assessments helped

Hamilton-Standard identify applicants'

strengths and

weaknesses

and became part of the data

subsequently used to accept or

reject candidates.

At

the assessment center, candidates

underwent two interviews--one oriented to

technical competence

and

the

other to business knowledge. They

also participated in a team-consensus

exercise aimed at

assessing

team

skills and decision-making capability.

The technical interview

presented candidates with a

flowchart of

the

manufacturing process and asked them to

identify areas in which they could

add value. Their

responses

enabled

interviewers to assess technical depth

and breadth, ability to learn,

and desire to be

cross-

functional.

The business interview

evaluated candidates' understanding of

material flow

processes,

configuration

management, computers, finance,

and human resources

practices. In the consensus

exercise,

participants

worked in small teams to

build a model airplane. Their

behaviors were observed and

assessed

on

such team-performance criteria as

participation, support of the process, interpersonal

skills, quality of

thought,

and flexibility.

At

the conclusion of the assessment center

activities, results of the tests,

interviews, and exercise

were

entered

into a spreadsheet to facilitate

comparison among candidates

and to help focus selection

decisions.

Evaluators

then met as a team to

examine the records, to discuss

each candidate, and to make

final

selections.

Consistent with Hamilton-Standard's

team-based culture, all hiring

decisions were made

by

group

consensus.

The

assessment center enabled

Hamilton-Standard to recruit extremely

capable people who fit well

with a

team-based

work structure. In less than

two years, the division was

able to hire, train, and retain a

talented,

cross-functional

workforce with certified

skills covering more than

fifty-two areas. To date, the

teams have

been

effective at improving customer-acceptance

rates while lowering costs,

thus making Hamilton-

Standard

a highly competitive supplier of

aerospace electronics.

Research

suggests that mentoring is relatively

prevalent in organizations. A survey of

1,250 top executives

showed

that about two-thirds had a

mentor or sponsor during

their early career stages,

when learning,

growth,

and advancement were most

prominent. The executives reported

that effective mentors

were

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

willing

to share knowledge and experience,

were knowledgeable about the

company and the use of

power,

and

were good counselors. In

contrast to executives who

did not have mentors,

those having them received

slightly

more compensation, had more

advanced college degrees,

had engaged in career

planning prior to

mentoring,

and were more satisfied

with their careers and

their work.

Although

research shows that

mentoring can have positive

outcomes, artificially creating

such relationships

when

they do not occur naturally is difficult.

Some organizations have developed

workshops in which

managers

are trained to become effective mentors.

Others, such as IBM and AT&T, include

mentoring as a

key

criterion for paying and

promoting managers. In a growing number

of cases, companies are

creating

special

mentoring programs for women

and minorities who have

traditionally had difficulties

cultivating

developmental

relationships.

Developmental

Training:

This

intervention helps employees

gain the skills and knowledge

for training and coaching

others. It may

include

workshops and training

materials oriented to human

relations, communications, active

listening,

and

mentoring. It can also

involve substantial investments in

education, such as tuition

reimbursement pro-

grams

that assist members in

achieving advanced degrees. Developmental

training interventions

generally

are

aimed at increasing the organization's

reservoir of skills and knowledge.

This enhances its capability

to

implement

personal and organizational

strategies.

A

large number of organizations offer

developmental training programs,

including Procter & Gamble,

Cisco

Systems, IBM, and Hewlett-Packard.

Many of these efforts are

directed at mid-career managers

who

generally

have good technical skills

but only rudimentary experience in

coaching others.

In-house

developmental

training typically involves preparatory

reading, short lectures, experiential

exercises, and case

studies

on such topics as active listening,

defensive communication, personal problem

solving, and

supportive

relationships. Participants may be

videotaped training and coaching

others, and the tapes may

be

reviewed

and critiqued by participants and staff.

Classroom learning is often rotated with

on-the-job expe-

riences,

and there is considerable

follow-up and recycling of learning.

Numerous consulting firms also

offer

workshops

and structured learning materials on

developmental training, and an extensive

practical literature

exists

in this area.

Work-Life

Balance Planning:

This

relatively new OD intervention helps

employees better integrate and

balance work and home

life.

Restructuring,

downsizing, and increased global

competition have contributed to longer

work hours and

more

stress. Baby-boomers approaching

fifty years of age and

others are rethinking their

priorities and

seeking

to restore some balance in a

work-dominated life. Organizations,

such as Corning Glass

Works,

Hewlett-Packard,

Infonet, and the City of Phoenix,

are responding to these concerns so they

can attract,

retain,

and motivate the best

workforce. More balanced

work and family lives

can benefit both

employees

and

the company through increased

creativity, morale, and

effectiveness, and reduced

turnover.

Work-life

balance planning involves a variety of

programs to help members better

manage the interface

between

work and family. These

include such organizational practices as

flexible hours, job sharing,

and

day

care, as well as interventions to

help employees identify and

achieve both career and

family goals. A

popular

program is called middlaning, a metaphor for a

legitimate, alternative career track

that

acknowledges

choices about living life in

the "fast lane Middlaning

helps people redesign their

work and

income-generating

activities so that more time and

energy are available for

family and personal needs.

It

involves

education in work addiction, guilt,

anxiety, and perfectionism; skill development in

work contract

negotiation;

examination of alternatives such as

changing careers, freelancing,

and entrepreneuring; and

exploration

of options for controlling financial

pressures by improving income/expense

ratios, limiting

"black

hole" worries such as

college tuition for children

and retirement expenses, and

replacing financial

worrying

with financial planning. Because

concerns about work-life

balance are unlikely to

abate and may

even

increase in the near future, we

can expect requisite OD

interventions, such as middlaning,

to

proliferate

throughout the public and

private sectors.

Job

Rotation and Challenging Assignments:

The

purpose of these interventions is to

provide employees with the

experience and visibility

needed for

career

advancement or with the challenge

needed to revitalize a stagnant career at

the maintenance stage.

Unlike

job pathing, which specifies a

sequence of jobs to reach a

career objective, job rotation

and

challenging

assignments are less planned

and may not be as oriented

to promotion opportunities.

Members

in the advancement stage may be

moved into new job areas

after they have demonstrated

competence

in a particular work specialty. Companies

such as Corning Glass Works,

Hewlett-Packard,

American

Crystal Sugar Company, and

Fidelity Investments identify "comers"

(managers under forty

years

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

old

with potential for assuming

top management positions) and

"hipos" (high-potential candidates)

and

provide

them with cross-divisional job

experiences during the advancement

stage. These job

transfers

provide

managers with a broader range of

skills and knowledge as well as

opportunities to display

their

managerial

talent to a wider audience of corporate executives.

Such exposure helps the organization

identify

members

who are capable of handling

senior executive responsibilities; it

helps the members

decide

whether

to seek promotion to higher positions or to particular

departments. To reduce the risk of

transferring

employees across divisions or functions,

some firms, such as Procter & Gamble,

Heublein, and

Continental

Can, have created "fallback

positions. These jobs are

identified before the transfer,

and

employees

are guaranteed that they can

return to them without negative

consequences if the transfers or

promotions

do not work out. Fallback positions

reduce the risk that employees in the

advancement stage

will

become trapped in a new job

assignment that is neither

challenging nor highly visible in the

company.

In

the maintenance stage,

challenging assignments can

help revitalize veteran employees by

providing

them

with new challenges and

opportunities for learning and

contribution. Research on enriched

jobs

suggests

that people are most

responsive to them during the first

one to three years on a job,

when

enriched

jobs are likely to be seen

as challenging and motivating.

People who have leveled

off and remain

on

enriched jobs for three

years or more tend to become

unresponsive to them. They are no

longer

motivated

and satisfied by jobs that

may no longer seem enriched. One

way to prevent this loss of

job

motivation,

especially among mid-career

employees who are likely to

remain on jobs for longer

periods of

time

than people in the establishment and

advancement phases, is to rotate workers

to new, more

challenging

jobs at about three-year intervals, or to redesign

their jobs at those times.

Such job changes

would

keep employees responsive to

challenging jobs and sustain

motivation and satisfaction

during the

maintenance

phase.

A

growing body of research

suggests that "plateaued employees"

(those with little chance of

further

advancement)

can have satisfying and

productive careers if they accept

their new role in the

company and

are

given challenging assignments with

high performance standards.

Planned rotation to jobs

requiring new

skills

can provide that challenge.

However, a firm's business strategy

and humans resources

philosophy

must

reinforce lateral (as opposed to strictly

vertical) job changes if plateaued

employees are to

adapt

effectively

to their new jobs. Firms

with business strategies

emphasizing stability and efficiency

of

operations,

such as the U.S. Post Office

and McDonald's, are likely

to have more plateaued

employees at

the

maintenance stage than are

companies with strategies

promoting development and growth,

such as

Microsoft

and Intel. The human

resources systems of firms with

stable growth strategies should

be

especially

aimed at helping plateaued

employees lower their

aspirations for promotion

and withdraw from

the

tournament mobility track. Moreover,

such firms should enforce high

performance standards so

that

high-performing

plateaued employees (solid citizens)

are rewarded, and low

performers (deadwood) are

encouraged

to seek help or to leave the

firm.

Dual-Career

Accommodations:

These

are practices for helping

employees cope with the

problems inherent in "dual

careers"--that is,

both

the

employee and a spouse or significant

other pursuing full-time careers.

Dual careers are becoming

more

prevalent

as women increasingly enter the

workforce. The U.S. Department of

Labor reports that

more

than

80 percent of all marriages

involve dual careers. Although

these interventions can apply to all

career

stages,

they are especially relevant during

advancement. One of the biggest problems

created by dual

careers

is job transfers, which are

likely to occur during the

advancement stage. Transfer to

another

location

usually means that the

working partner must also

relocate. In many cases, the

company employing

the

partner must either lose the employee or

arrange a transfer to the same

location. Similar problems

can

occur

in recruiting employees. A recruit may

not join an organization if its

location does not provide

career

opportunities

for the partner.

Because

partners' careers can affect the

recruitment and advancement of employees,

organizations are

devising

policies to accommodate dual-career

employees. A survey of companies reported

the following

dual-career

accommodations: recognition of problems

in dual careers, help with relocation,

flexible working

hours,

counseling for dual-career

employees, family daycare

centers, improved career

planning, and

policies

making

it easier for two members of

the same family to work in the

same organization or department.

Some

companies have also

established cooperative arrangements with

other firms to provide sources

of

employment

for the other partner. General Electric,

for example, has created a

network with other firms

to

share

information about job opportunities

for dual-career

couples.

Consultative

Roles:

These

provide late-career employees

with opportunities to apply their

wisdom and knowledge to

helping

others

develop in their careers and

solve organizational problems. Such

roles, which can be

structured

around

specific projects or problems,

involve Offering advice and

expertise to those responsible

for

resolving

the issues. For example, a

large aluminum forging manufacturer

was having problems

developing

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

accurate

estimates of the cost of producing

new products. The sales

and estimating departments

lacked the

production

experience to make accurate

bids for potential new

business, thus either losing customers

or

losing

money on products. The

company temporarily assigned an

old-line production manager

who was

nearing

retirement to consult with the salespeople

and estimators about bidding on

new business. The

consultant

applied his years of forging

experience to help the sales

and estimating people make

more

accurate

estimates. In about a year, the

sales staff and estimators

gained the skills and invaluable

knowledge

necessary

to make more accurate bids.

Perhaps equally important, the

pre-retirement production manager

felt

that he had made a significant

contribution to the company--something he

had not experienced

for

years.

In

contrast to mentoring roles, consultative

roles are not focused

directly on guiding or sponsoring

younger

employees'

careers. They are directed

at helping others deal with

complex problems or projects.

Similarly,

in

contrast to managerial positions, consultative

roles do not include the performance

evaluation and

control

inherent in being a manager. They

are based more on wisdom

and experience than on

authority.

Consequently,

consultative roles provide an effective

transition for moving pre-retirement

managers into

more

support-staff positions. They free up managerial

positions for younger employees while

allowing

older

managers to apply their experience

and skills in a more

supportive and less threatening

way than

might

be possible from a strictly managerial

role.

When

implemented well, consultative roles can

increase the organization's

problem-solving capacity.

They

enable

experienced employees to apply their

skills and knowledge to resolving

important problems, and

can

increase

members' work satisfaction in the

maintenance or withdrawal career

stages. They provide

senior

employees

with meaningful work as they begin to move

from the workforce to retirement.

Phased

Retirement:

This

provides older employees with an

effective way of withdrawing from the

organization and establishing

a

productive leisure life. It

includes various forms of part-time work.

Employees gradually devote less

of

their

time to the organization and more time to

leisure pursuits (which to some

might include developing a

new

career). Phased retirement allows

older employees to make a

gradual transition from organizational

to

leisure

life. It enables them to continue

contributing to the firm while it

gives them time to establish

themselves

outside of work. For

example, people may use the

extra time off work to take

courses, to gain

new

skills and knowledge, and to

create opportunities for

productive leisure. IBM, for

example, offers

tuition

rebates for courses on any

topic taken within three

years of retirement. Many IBM

pre-retirees have

used

this program to prepare for second

careers.

Equally

important, phased retirement lessens the

reality shock often experienced by

those who retire all

at

once.

It helps employees grow

accustomed to leisure life

and withdraw emotionally

from the organization.

A

growing number of companies have

some form of phased

retirement.

Organization

Decline and Career Halt:

Decreasing

and uneven demand for

products and services; growing

numbers of mergers,

acquisitions,

divestitures,

and failures; and increasing

restructurings to operate leaner

and more efficiently have

resulted

in

layoffs, reduced job opportunities,

and severe career disruptions

for a large number of managers

and

employees.

People

inevitably experience a halt in

their career development and

progression, resulting in

dangerous

increases

in personal stress, financial and

family disruption, and loss

of self-esteem. Fortunately, a

growing

number

of organizations are managing

decline in ways that are

effective for both the organization and

the

employee.

Organizations

have also developed human

resources practices for

managing decline in those

situations

where

layoffs are unavoidable, such as plant

closings, divestitures, and

business failures. The

following

methods

can help people deal more

effectively with layoffs and

premature career

halts:

�

Equitable

layoff policies spread

throughout organizational ranks, rather

than focused on

specific

levels

of employees, such as shop-floor

workers or middle

managers

�

Keeping

people informed about organizational problems and

possibilities of layoffs so that they

can

reduce ambiguity and prepare

themselves for job

changes

�

Setting

realistic expectations, rather than

offering excessive hope and

promises, so that

employees

can

plan for the organization's future

and for their

own

�

Generous

relocation and transfer policies

that help people make the

transition to a new

work

situation

�

Helping

people find new jobs,

including outplacement services

and retraining

�

Treating

people with dignity and

respect, rather than belittling or

humiliating them because they

are

unfortunate enough to be in a declining business

that can no longer afford to employ

them.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

In

today's environment, organization

decline, downsizing, and restructuring

will continue. OD practitioners

are

likely to become increasingly

involved in helping people manage

career dislocation and halt.

Table of Contents:

- The Challenge for Organizations:The Growth and Relevance of OD

- OD: A Unique Change Strategy:OD consultants utilize a behavioral science base

- What an “ideal” effective, healthy organization would look like?:

- The Evolution of OD:Laboratory Training, Likert Scale, Scoring and analysis,

- The Evolution of OD:Participative Management, Quality of Work Life, Strategic Change

- The Organization Culture:Adjustment to Cultural Norms, Psychological Contracts

- The Nature of Planned Change:Lewin’s Change Model, Case Example: British Airways

- Action Research Model:Termination of the OD Effort, Phases not Steps

- General Model of Planned Change:Entering and Contracting, Magnitude of Change

- The Organization Development Practitioner:External and Internal Practitioners

- Creating a Climate for Change:The Stabilizer Style, The Analyzer Style

- OD Practitioner Skills and Activities:Consultant’s Abilities, Marginality

- Professional Values:Professional Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, Technical Ineptness

- Entering and Contracting:Clarifying the Organizational Issue, Selecting an OD Practitioner

- Diagnosing Organizations:The Process, The Performance Gap, The Interview Data

- Organization as Open Systems:Equifinality, Diagnosing Organizational Systems

- Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Methods for Collecting Data, Observations

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Sampling, The Analysis of Data

- Designing Interventions:Readiness for Change, Techno-structural Interventions

- Leading and Managing Change:Motivating Change, The Life Cycle of Resistance to Change

- Leading and managing change:Describing the Core Ideology, Commitment Planning

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Measurement

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Research Design

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Group Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Leadership and Authority, Group Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Third-Party Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Building, Team Building Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Management Styles

- Organization Process Approaches:Application Stages, Microcosm Groups

- Restructuring Organizations:Structural Design, Process-Based Structures

- Restructuring Organizations:Downsizing, Application Stages, Reengineering

- Employee Involvement:Parallel Structures, Multiple-level committees

- Employee Involvement:Quality Circles, Total Quality Management

- Work Design:The Engineering Approach, Individual Differences, Vertical Loading

- Performance Management:Goal Setting, Management by Objectives, Criticism of MBO

- Developing and Assisting Members:Career Stages, Career Planning, Job Pathing

- Developing and Assisting Members:Culture and Values, Employee Assistance Programs

- Organization and Environment Relationships:Environmental Dimensions, Administrative Responses

- Organization Transformation:Sharing the Vision, Three kinds of Interventions

- The Behavioral Approach:The Deep Assumptions Approach

- Seven Practices of Successful Organizations:Training, Sharing Information