|

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

38

Work

Design

Work

design has been researched

and applied extensively in organizations.

Recently, organizations

have

tended

to combine work design with

formal structure and

supporting changes in goal

setting, reward sys-

tems,

work environment, and other

performance management practices.

These organizational factors

can

help

structure and reinforce the kinds of work

behaviors associated with

specific work designs

We

will examine three

approaches to work design. First, the

engineering approach, which

focuses on

efficiency

and simplification, and

results in traditional job

and work group designs.

Second approach to

work

design rests on motivational

theories and attempts to enrich the

work experience. The third

and most

recent

approach to work design

derives from socio-technical

systems methods, and seeks

to optimize both

the

social and the technical

aspects of work

systems.

The

Engineering Approach:

The

oldest and most prevalent

approach to designing work is

based on engineering concepts

and methods.

It

proposes that the most

efficient work designs can

be determined by clearly specifying the

tasks to be

performed,

the work methods to be used,

and the work flow among

individuals. The engineering

approach

is

based on the pioneering work of Frederick

Taylor, the father of scientific

management. He developed

methods

for analyzing and designing

work and laid the foundation

for the professional field of

industrial

engineering.

The

engineering approach scientifically

analyzes workers' tasks to

discover those procedures

that produce

the

maximum output with the

minimum input of energies

and resources. This

generally results in

work

designs

with high levels of

specialization and specification. Such

designs have several

benefits: they allow

workers

to learn tasks rapidly; they

permit short work cycles so

performance can take place

with little or no

mental

effort; and they reduce

costs because lower-skilled people can be

hired and trained easily and

paid

relatively

low wages.

The

engineering approach produces

two kinds of work design:

traditional jobs and

traditional work

groups.

When

the work can be completed by

one person, such as with

bank tellers and telephone

operators,

traditional

jobs are created. These

jobs tend to be simplified,

with routine and repetitive

tasks having clear

specifications

concerning time and motion.

When the work requires

coordination among people,

such as

on

automobile assembly lines,

traditional work groups are

developed. They are composed

of members

performing

relatively routine yet related

tasks. The overall group

task is typically broken

into simpler,

discrete

parts (often called jobs).

The tasks and work

methods are specified for

each part, and the parts

are

assigned

to group members. Each

member performs a routine and

repetitive part of the group

task.

Members'

separate task contributions

are coordinated for overall

task achievement through

such external

controls

as schedules, rigid work flows,

and supervisors. In the 1950s

and 1960s, this method of

work

design

was popularized by the assembly lines of

American automobile manufacturers and

was an important

reason

for the growth of American industry

following World War

II.

The

engineering approach to job

design is less an OD intervention

than a benchmark in history.

Critics of

the

approach argue that the method

ignores workers' social and

psychological needs. They suggest

that the

rising

educational level of the workforce and

the substitution of automation for menial

labor point to the

need

for more enriched forms of

work in which people have

greater discretion and are

more challenged.

Moreover,

the current competitive climate requires a

more committed and involved

workforce able to

make

online decisions and to develop

performance innovations. Work

designed with the employee in

mind

is

more humanly fulfilling and

productive than that

designed in traditional ways.

However, it is important to

recognize

the strengths of the engineering

approach. It remains an important

work design

intervention

because

its immediate cost savings

and efficiency can be measured readily,

and because it is well

understood

and

easily implemented and

managed.

The

Motivational Approach:

The

motivational approach to work

design views the effectiveness of

organizational activities primarily as

a

function

of member needs and

satisfaction, and seeks to

improve employee performance

and satisfaction

by

enriching jobs. The motivational method

provides people with opportunities for

autonomy,

responsibility,

closure (that is, doing a

complete job), and

performance feedback. Enriched

jobs are popular

in

the United States at such

companies as AT&T Universal Card,

TRW, Dayton Hudson, and

GTE.

The

motivational approach usually is

associated with the research of Herzberg

and of Hackman and

Oldham.

Herzberg's two-factor theory of

motivation proposed that

certain attributes of work, such

as

opportunities

for advancement and

recognition, which he called motivators,

help increase job

satisfaction.

Other

attributes that Herzberg called hygiene

factors, such as company

policies, working conditions,

pay,

and

supervision, do not produce

satisfaction but rather prevent

dissatisfaction--important

contributors

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

because

only satisfied workers are

motivated to produce. Successful

job enrichment experiments at

AT&T,

Texas

Instruments, and Imperial Chemical

Industries helped to popularize job enrichment in the

1960s.

Although

Herzberg's motivational factors

sound appealing, increasing

doubt has been cast on

the

underlying

theory. Motivation and

hygiene factors are

difficult to put into

operation and measure, and

that

makes

implementation and evaluation of the

theory difficult. Furthermore, important

worker characteristics

that

can affect whether people will respond

favorably to job enrichment were

not included in his

theory.

Finally,

Herzberg's failure to involve

employees in the job enrichment process

itself does not suit most

OD

practitioners

today. Consequently, a second,

well-researched approach to job

enrichment has been favored.

It

focuses on the attributes of the work

itself and has resulted in a

more scientifically acceptable theory

of

job

enrichment than Herzberg's model. The

research of Hackman and Oldham

represents this more

recent

trend

in job enrichment.

The

Core Dimensions of

Jobs:

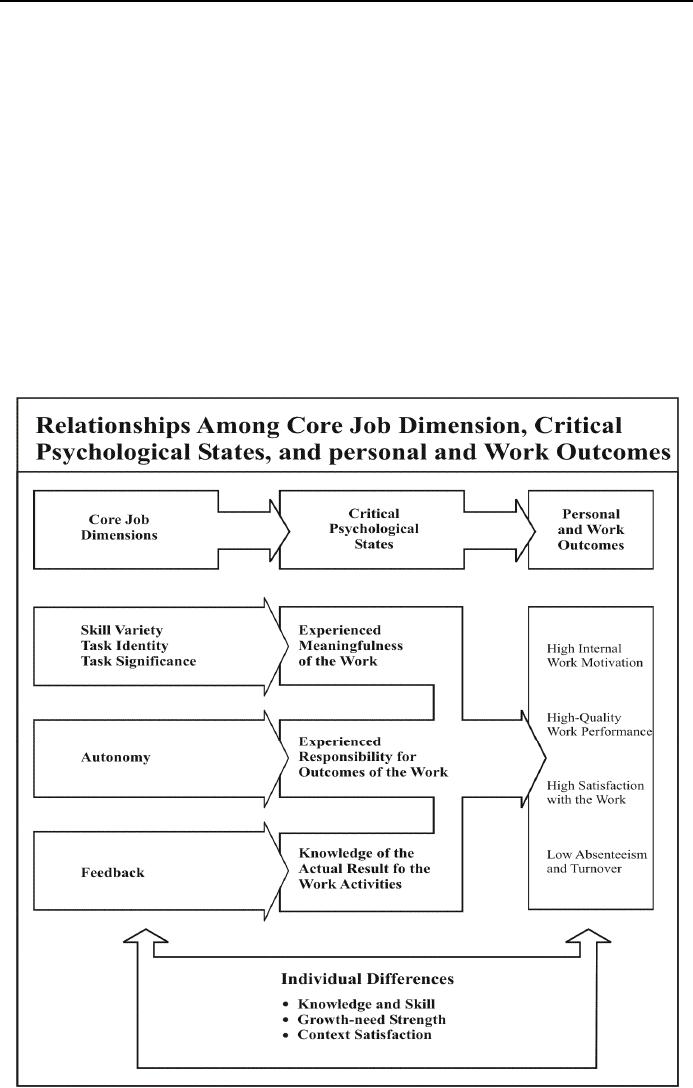

Considerable

research has been devoted to

defining and understanding core

job dimensions. Figure 50

summarizes

the Hackman and Oldham model of job

design. Five core dimensions

of work affect three

critical

psychological states, which in

turn produce personal and

job outcomes. These outcomes

include

high

internal work motivation,

high-quality work performance,

satisfaction with the work,

and low

absenteeism

and turnover. The five

core job dimensions--skill

variety, task identity, task

significance,

autonomy,

and feedback from the work

itself--are described below

and associated with the

critical

psychological

states that they

create.

Figure

50

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Skill

Variety, Task Identity, and

Task Significance:

These

three core job

characteristics influence the extent to which

work is perceived as meaningful.

Skill

variety

refers to the number and types of

skills used to perform a particular

task. Employees at

Lechmere's,

a

retail chain in Florida, can

work as warehouse stock

clerks, cashiers, and

salespeople. The more tasks

an

individual

performs, the more meaningful the job

becomes. When skill variety is

increased by moving a

person

from one job to another, a

form of job enrichment called

job rotation is accomplished.

However,

simply

rotating a person from one

boring job to another is not

likely to produce the outcomes

associated

with

a fully enriched job.

Task

identity describes the extent to which an

individual performs a whole piece of

work. For example, an

employee

who completes an entire wheel

assembly for an airplane,

including the tire, chassis,

brakes, and

electrical

and hydraulic systems has

more task identity and

will perceive the work as

more meaningful than

someone

who only assembles the

braking subsystem. Job

enlargement, another form of job

enrichment

that

combines increases in skill variety

with task identity, blends

several narrow jobs into one

larger,

expanded

job. For example, separate

machine set-up, machining,

and inspection jobs might be

combined

into

one. This method can

increase meaningfulness, job

satisfaction, and motivation

when employees

comprehend

and like the greater task

complexity.

Task

significance represents the impact

that the work has on others.

In jobs with high task

significance,

such

as nursing, consulting, or manufacturing something

like sensitive parts for the

space shuttle, the

importance

of successful task completion

creates meaningfulness for the

worker.

Experienced

meaningfulness is expressed as an average

of these three dimensions.

Thus, although it is

advantageous

to have high amounts of

skill variety, task

identity, and task

significance, a strong

emphasis

on

any one of the three

dimensions can, at least

partially, make up for

deficiencies in the other

two.

Autonomy:

This

refers to the amount of independence, freedom,

and discretion that the employee

has to schedule and

perform

tasks. Salespeople, for

example, often have

considerable autonomy in how they

contact, develop,

and

close new accounts, whereas

assembly-line workers often

have to adhere to work

specifications clearly

detailed

in a policy-and-procedure manual. Employees

are more likely to

experience responsibility for

their

work

outcomes when high amounts of autonomy

exist.

Feedback

from the Work

Itself:

This

core dimension represents the information

that workers receive about the

effectiveness of their

work.

It

can derive from the work itself, as when

determining whether an assembled part

functions properly or it

can

come from such external

sources as reports on defects, budget

variances, customer satisfaction,

and the

like.

Because feedback from the

work itself is direct and

generates intrinsic satisfaction, it is

considered

preferable

to feedback from external

sources.

Skill

variety, task identity, and

task significance jointly

determine jobs

meaningfulness.

These

three dimensions are treated

as one dimension in the Motivation

Potential Score formula, or

MPS:

Motivation

Potential Score (MPS) =

Job

Meaningfulness x

Autonomy

x

Job

Feedback

The

first variable in the formula, job

meaningfulness, is a function of skill

variety, task identity, and

task

significance.

Thus the formula can further

be refined:

Motivation

Potential Score (MPS) = [Skill

Variety + Task identity +

Task significance] x

Autonomy

x Job Feedback

3

A

score of near zero on either the autonomy

or job feedback dimension will produce an

MPS of near zero.

Whereas

a number near zero on skill

variety, task identity or

task significance will

reduce the total MPS,

but

will

not completely undermine the motivational

potential of a job.

We

can predict employee's psychological

state from this

formula.

High

scores in Skill variety,

task variety, and task

significance result in the employee's

experiencing

meaningfulness

in job, such as believing the

work to be important, valuable,

and worthwhile.

A

high score in the autonomy dimension

leads to the employee's feeling

personally responsible

and

accountable

for the results of the

work.

A

high score in the job

feedback dimension is an indication that

the employee has an understanding of

how

he

or she is performing the

job.

Self

managed teams (to be

discussed later) have high

scores on all the five core

job dimensions.

Individual

Differences:

Not

all people react in similar

ways to job enrichment interventions.

Individual differences--among

them,

a

worker's knowledge and skill

levels, growth-need strength, and

satisfaction with contextual

factors--

moderate

the relationships among core dimensions,

psychological states, and

outcomes. "Worker

knowledge

and skill" refers to the education

and experience levels

characterizing the workforce. If

employees

lack the appropriate skills, for

example, increasing skill variety

may not improve a

job's

meaningfulness.

Similarly, if workers lack the intrinsic

motivation to grow and develop personally,

attempts

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

to

provide them with increased autonomy

may be resisted. Finally, contextual

factors include reward

systems,

supervisory style, and co-worker

satisfaction. When the employee is

unhappy with the work

context,

attempts to enrich the work itself

may be unsuccessful.

Application

Stages:

The

basic steps for job

enrichment as described by Hackman and

Oldham include making a thorough

diagnosis

of the situation, forming natural work units,

combining tasks, establishing client

relationships,

vertical

loading, and opening feedback

channels.

Making

a Thorough Diagnosis:

The

most popular method of diagnosing a

job is through the use of the

Job Diagnostic Survey (JDS) or

one

of

its variations. An important output of

the JDS is the motivating potential

score, which is a function of

the

three psychological states--experienced

meaningfulness, autonomy, and

feedback. The survey can

be

used

to profile one or more jobs,

to determine whether motivation and

satisfaction are really problems

or

whether

the job is low in motivating

potential, and to isolate

specific job aspects that

are causing

difficulties.

Forming

Natural Work

Units:

As

much as possible, natural work units

should be formed. Although there

may be a number of

technological

constraints, interrelated task activities should be

grouped together. The basic question

in

forming

natural work units is "How can

one increase 'ownership' of the task?"

Forming such natural units

increases

two of the core dimensions--task identity

and task significance--that

contribute to the

meaningfulness

of work.

Combining

Tasks:

Frequently,

divided jobs can be put

back together to form a new

and larger one. In the

Medfield,

Massachusetts,

plant of Corning Glass

Works, the task of assembling

laboratory hotplates was

redesigned

by

combining a number of previously separate

tasks. After the change,

each hotplate was

completely

assembled,

inspected, and shipped by

one operator, resulting in increased

productivity of 84 percent.

Controllable

rejects dropped from 23

percent to less than 1

percent, and absenteeism

dropped from 8

percent

to less than 1 percent. A later

analysis indicated that the change in

productivity was the result of

the

intervention.

Combining tasks increases

task identity and allows a

worker to use a greater variety of

skills.

The

hotplate assembler can

identify with a product

finished for shipment, and

self-inspection of his or her

work

adds greater task

significance, autonomy, and

feedback from the job

itself.

Establishing

Client Relationships:

When

jobs are split up, the typical

worker has little or no

contact with, or knowledge of, the

ultimate user

of

the product or service. Improvements

often can be realized

simultaneously on three of the

core

dimensions

by encouraging and helping

workers to establish direct relationships

with the clients of

their

work.

For example, when a typist

in a typing pool is assigned to a

particular department, feedback

increases

because

of the additional opportunities for

praise or criticism of his or

her work. Because of the

need to

develop

interpersonal skills in maintaining the client relationship,

skill variety may increase. If the

worker is

given

personal responsibility for deciding how

to manage relationships with clients,

autonomy is increased.

Three

steps are needed to create

client relationships: (1) the

client must be identified;

(2) the contact

between

the client and the worker needs to be

established as directly as possible;

and (3) criteria and

procedures

are needed by which the

client can judge the quality

of the product or service received

and relay

those

judgments back to the worker.

For example, even

customer-service representatives and

data-entry

operations

can be set up so that people

serve particular clients. In the hotplate

department, personal

nametags

can be attached to each instrument.

The Indiana Bell Telephone

Company found

substantial

improvements

in satisfaction and performance when

telephone directory compilers were given

accountabil-

ity

for a specific geographic

area.

Vertical

Loading:

The

intent of vertical loading is to decrease

the gap between doing the

job and controlling the job.

A

vertically

loaded job has responsibilities

and controls that formerly

were reserved for

management. Vertical

loading

may well be the most crucial

of the job-design principles. Autonomy is invariably

increased. This

approach

should lead to greater feelings of

personal accountability and responsibility

for the work

outcomes.

For example, at an IBM plant

that manufactures circuit boards

for personal computers,

assembly

workers

were trained to measure the accuracy

and speed of production

processes and to test the

quality of

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

finished

products. Their work is more

''whole/' they are more

autonomous, and the engineers

who used to

measure

and test are free to

design better products and

more efficient ways to

manufacture them.

Loss

of vertical loading usually occurs

when someone has made a

mistake. Once a supervisor

steps in, the

responsibility

may be removed indefinitely.

For example, many skilled

machinists have to complete

forms

to

have maintenance people work on a

machine. The supervisor automatically

signs the slip rather than

al-

lowing

the machinist either to repair the machine or

ask directly for maintenance

support.

Opening

Feedback Channels:

In

almost all jobs, approaches

exist to open feedback channels

and help people learn whether

their

performance

is remaining at a constant level, improving, or

deteriorating. The most advantageous

and least

threatening

feedback occurs when a

worker learns about performance as the

job is performed. In the

hotplate

department at Corning Glass Works,

assembling the entire instrument and

inspecting it

dramatically

increased the quantity and

quality of performance information

available to the operators. Data

given

to a manager or supervisor often

can be given directly to the employee.

Computers and other

automated

operations can be used to provide people

with data not currently

accessible to them.

Many

organizations

simply have not realized the

motivating impact of direct, immediate

feedback.

Barriers

to Job Enrichment:

As

the application of job enrichment has

spread, a number of obstacles to significant

job restructuring have

been

identified. Most of these

barriers exist in the organizational

context within which the job

design is

executed.

Other organizational systems and

practices, whether technical, managerial,

or personnel, can

affect

both the implementation of job enrichment

and the lifespan of whatever changes

are made.

At

least four organizational systems

can constrain the implementation of

job enrichment:

1.

The technical system. The

technology of an organization can limit

job enrichment by constraining the

number

of ways jobs can be changed.

For example, long-linked technology

like that found on an

assembly

line

can be highly programmed and

standardized, thus limiting the amount of

employee discretion that is

possible.

Technology also may set an

"enrichment ceiling." Some

types of work, such as

continuous-

process

production systems, may be naturally

enriched so there is, little

more that can be gained

from a job

enrichment

intervention.

2.

The personnel system. Personnel

systems can constrain job

enrichment by creating formalized

job

descriptions

that are rigidly defined

and limit flexibility in

changing people's job

duties. For example,

many

union

agreements include such narrowly

defined job descriptions

that major renegotiation between

man-

agement

and the union must occur

before jobs can be significantly

enriched.

3.

The control system. Control

systems, such as budgets,

production reports, and

accounting practices,

can

limit the complexity and

challenge of jobs within the

system. For example, a

company working on a

government

contract may have such strict

quality control procedures

that employee discretion is

effectively

curtailed.

4.

The supervisory system. Supervisors

determine to a large extent the amount of autonomy

and

feedback

that subordinates can

experience. To the extent that

supervisors use autocratic

methods and

control

work-related feedback, jobs will be

difficult, if not impossible, to

enrich.

Once

these implementation constraints

have been overcome, other

factors determine whether the

effects

of

job enrichment are strong and

lasting. Consistent with the contingency

approach to OD, the

staying

power

of job enrichment depends largely on

how well it fits and is

supported by other organizational

practices,

such as those associated

with training, compensation,

and supervision. These

practices need to be

congruent

with and to reinforce jobs having

high amounts of discretion, skill

variety, and meaningful

feedback.

The

Sociotechnical Systems

Approach:

The

sociotechnical systems (STS)

approach currently is the most extensive

body of scientific and applied

work

underlying employee involvement

and innovative work designs.

Its techniques and design

principles

derive

from extensive action research in

both public and private

organizations across diverse

national

cultures.

This section reviews the conceptual

foundations of the STS approach

and then describes its

most

popular

application--self-managed work

teams.

Conceptual

Background:

Sociotechnical

systems theory was developed

originally at the Tavistock Institute of

Human Relations in

London

and has spread to most

industrialized nations in a little more

than fifty years. In Europe

and

particularly

Scandinavia, STS interventions

are almost synonymous with

work design and

employee

involvement.

In Canada and the United

States, STS concepts and

methods underlie many of the

innovative

work

designs and team-based

structures that are so prevalent in

contemporary organizations. Intel

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Corporation,

United Technologies, General Mills, and

Procter & Gamble are among the

many

organizations

applying the STS approach to

transforming how work is

designed and performed.

STS

theory is based on two fundamental

premises: that an organization or work

unit is a combined, social-

plus-technical

system (sociotechnical), and

that this system is open in relation to

its environment.

Sociotechnical

System:

The

first assumption suggests

that whenever human beings

are organized to perform

tasks, a joint system

is

operating--a

sociotechnical system. This system

consists of two independent but

related parts: a social

part

including

the people performing the tasks and the

relationships among them, and a

technical part

comprising

the tools, techniques, and methods

for task performance. These

two parts are independent

of

each

other because each follows a

different set of behavioral laws.

The social part operates

according to

biological

and psychosocial laws,

whereas the technical part

functions according to mechanical

and physical

laws.

Nevertheless, the two parts

are related because they

must act together to accomplish

tasks. Hence, the

term

sociotechnical signifies the joint

relationship that must occur

between the social and

technical parts,

and

the word system communicates

that this connection results in a unified

whole.

Because

a sociotechnical system is composed of

social and technical parts,

it follows that it will

produce

two

kinds of outcomes: products, such as

goods and services; and

social and psychological

consequences,

such

as job satisfaction and commitment.

The key issue is how to

design the relationship between the

two

parts

so that both outcomes are

positive (referred to as joint

optimization). Sociotechnical

practitioners

design

work and organizations so

that the social and

technical parts work well

together, producing high

levels

of product and human

satisfaction. This effort contrasts

with the engineering approach to

designing

work,

which focuses on the technical component,

worries about fitting people in later,

and often leads to

mediocre

performance at high social

costs. The STS approach

also contrasts with the

motivational

approach

that views work design in

terms of human fulfillment

and can lead to satisfied

employees but

inefficient

work processes.

Environmental

Relationship:

The

second major premise underlying

STS theory is that such

systems are open to their environments.

As

discussed

earlier, open systems must interact with

their environments to survive and develop.

The

environment

provides the STS with necessary inputs of

energy, raw materials, and

information, and the

STS

provides the environment with products

and services. The key

issue here is how to design

the interface

between

the STS and its environment

so that the system has

sufficient freedom to function

while

exchanging

effectively with the environment. In what

is typically called boundary management,

STS

practitioners

structure environmental relationships

both to protect the system

from external disruptions

and

to facilitate the exchange of necessary

resources and information.

This enables the STS to

adapt to

changing

conditions and to influence the

environment in favorable directions.

In

summary, STS theory suggests

that effective work systems

jointly optimize the relationship

between

their

social and technical parts.

Moreover, such systems

effectively manage the boundary

separating and

relating

them to the environment. This allows them to

exchange with the environment

while protecting

themselves

from external disruptions.

Self-Managed

Work Teams:

The

most prevalent application of the STS

approach is self-managed work

teams. Alternatively referred to

as

self-directed, self-regulating, or high-performance

work teams, these work

designs consist of

members

performing

interrelated tasks. Self-managed teams

typically are responsible

for a complete product

or

service,

or a major part of a larger production

process. They control members'

task behaviors and

make

decisions

about task assignments and

work methods. In many cases,

the team sets its own

production goals

within

broader organizational limits and may be

responsible for support services,

such as maintenance,

purchasing,

and quality control. Team

members generally are

expected to learn many if

not all of the jobs

within

the team's control and

frequently are paid on the basis of

knowledge and skills rather than

seniority.

When

pay is based on performance,

team rather than individual

performance is the standard.

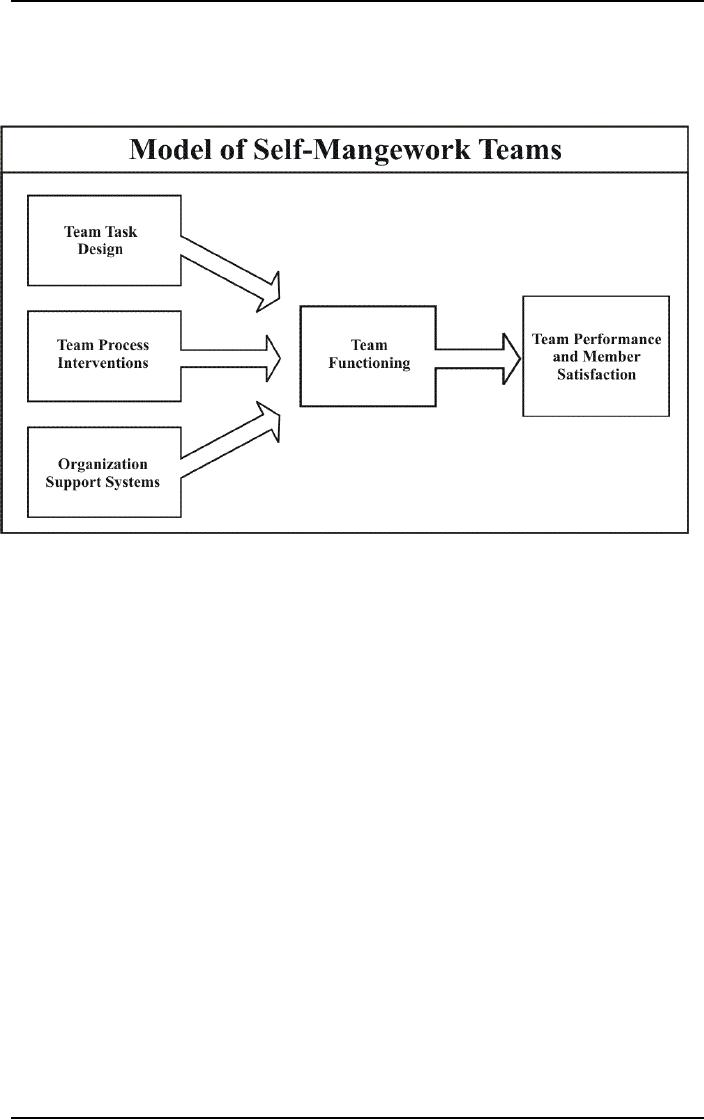

Figure

51 is a model explaining how self-managed

work teams perform. It

summarizes current STS

research

and shows how teams

can be designed for high

performance. Although the model is based

mainly

on

experience with teams that

perform the daily work of the organization

(work teams), it also

has

relevance

to other team designs, such

as problem-solving teams, management

teams, cross-functional

integrating

teams, and employee

involvement teams. The model

shows that team performance

and member

satisfaction

follow directly from how

well the team functions: how

well members communicate

and

coordinate

with each other, resolve

conflicts and problems, and

make and implement

task-relevant

decisions.

Team functioning, in turn, is influenced

by three major inputs: team task

design, team process

interventions,

and organization support systems.

Because these inputs affect

how well teams function

and

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

subsequently

perform, they are key

intervention targets for

designing and implementing self-managed

work

teams.

Figure:

51

Team

Task Design:

Self-managed

work teams are responsible

for performing particular tasks;

consequently, how the team

is

designed

for task performance can

have a powerful influence on how

well it functions. Task

design

generally

follows from the team's

mission and goals that

define the major purpose of the team and

provide

direction

for task achievement. When a

team's mission and goals

are closely aligned with

corporate strategy

and

business objectives, members

can see how team

performance contributes to organization success.

This

can

increase member commitment to team

goals.

Team

task design links members'

behaviors to task requirements

and to each other. It

structures member

interactions

and performances. Three task

design elements are

necessary for creating

self-managed work

teams:

task differentiation, boundary control,

and task control. Task

differentiation involves the extent to

which

the team's task is autonomous

and forms a relatively self-completing whole. High

levels of task

differentiation

provide an identifiable team boundary

and a clearly defined area

of team responsibility. At

Johnsonville

Sausage, for example,

self-managed teams comprise

seven to fourteen members.

Each team is

large

enough to accomplish a set of interrelated

tasks but small enough to

allow face-to-face meetings

for

coordination

and decision making. In many

hospitals, self-managed nursing teams

are formed around

interrelated

tasks that together produce a relatively

whole piece of work. Thus,

nursing teams may be

responsible

for particular groups of patients,

such as those in intensive care or

undergoing cancer treat-

ments,

or they may be accountable for

specific work processes,

such as those in the laboratory,

pharmacy,

or

admissions office.

Boundary

control involves the extent to which

team members can influence

transactions with their

task

environment--the

types and rates of inputs

and outputs. Adequate boundary control

includes a well-

defined

work area; group responsibility

for boundary-control decisions,

such as quality assurance

(which

reduces

dependence on external boundary regulators,

such as inspectors); and

members sufficiently trained

to

perform tasks without relying heavily on

external resources. Boundary control

often requires

deliberate

cross-training

of team members to take on a variety of

tasks. This makes members

highly flexible and

adaptable

to changing conditions. It also reduces

the need for costly overhead

because members can

perform

many of the tasks typically assigned to

staff experts, such as those in

quality control, planning,

and

maintenance.

Task

control involves the degree to which

team members can regulate

their own behavior to

provide

services

or to produce finished products. It

includes the freedom to choose work

methods, to schedule

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

activities,

and to influence production goals to

match both environmental and

task demands. Task

control

relies

heavily on team members having the power

and authority to manage equipment,

materials, and other

resources

needed for task performance.

This "work authority" is essential if

members are to take

responsibility

for getting the work accomplished.

Task control also requires

that team members

have

accurate

and timely information about

team performance to allow them to

detect performance

problems

and

make necessary

adjustments.

Task

control enables self-managed

work teams to observe and

control technical variances as

quickly and as

close

to their source as possible.

Technical variances arise

from the production process

and represent

significant

deviations from specific goals or

standards. In manufacturing; for example,

abnormalities in raw

material,

machine operation, and work

flow are sources of variance

that can adversely affect the

quality and

quantity

of the finished product. In service

work, out-of-the-ordinary requests,

special favors or treatment,

or

unique demands create variances

that can place stress on the

process. Technical variances

traditionally

are

controlled by support staff and

managers, but this can take

time and add greatly to

costs. Self-managed

work

teams, on the other hand,

have the freedom, skills, and

information needed to control

technical

variances

online when they occur. This affords

timely responses to production

problems and reduces

the

amount

of staff overhead needed.

Team

Process interventions:

A

second key input to team

functioning involves team

process interventions. As discussed

earlier teams

may

develop ineffective social processes

that impede functioning and

performance, such as

poor

communication

among members, dysfunctional roles

and norms, and faulty

problem solving and

decision

making.

Team process interventions,

such as process consultation and

team building, can resolve

such

problems

by helping members address

process problems and moving

the team to a more mature

stage of

development.

Because self-managed work

teams need to be self-reliant, members

generally acquire

their

own

team process skills. They

may attend appropriate training programs

and workshops or they may

learn

on

the job by working with OD practitioners

to conduct process interventions on their

own teams.

Although

members' process skills

generally are sufficient to

resolve most of the team's

process problems,

OD

experts occasionally may

need to supplement the team's

skills and help members

address problems

that

they are unable to

resolve.

Organization

Support Systems:

The

final input to team

functioning is the extent to which the

larger organization is designed to

support

self-managed

work teams. The success of

such teams clearly depends

on support systems that are

quite

different

from traditional methods of

managing. For example, a

bureaucratic, mechanistic organization

is

not

highly conducive to self-managed teams.

An organic structure, with

flexibility among units,

relatively

few

formal rules and procedures,

and decentralized authority, is

much more likely to support

and enhance

the

development of self-managed work teams.

This explains why such teams

are so prevalent in high-

involvement

organizations. Their different

features, such as flat, lean

structures, open information

systems,

and

team-based selection and

reward practices, all reinforce teamwork

and responsible

self-management.

A

particularly important support system

for self-managed work teams

is the external leadership. Self-

managed

teams exist along a spectrum

from having only mild influence

over their work to

near-autonomy.

In

many circumstances, such

teams take on a variety of functions

traditionally handled by

management.

These

can include assigning members to

individual tasks, determining the methods

of work, scheduling,

setting

production goals, and

selecting and rewarding members.

These activities do not make

external

supervision

obsolete, however. That leadership

role usually is changed to

two major functions:

working

with

and developing team members,

and assisting the team in

managing its

boundaries.

Working

with and developing team

members is a difficult process

and requires a different

style of managing

than

do traditional systems. The

team leader (often called a

team facilitator) helps team

members organize

themselves

in a way that allows them to

become more independent and

responsible. She or he must

be

familiar

with team-building approaches and

must assist members in learning the

skills to perform their

jobs.

Recent

research suggests that the

leader needs to provide

expertise in self-management. This

may include

encouraging

team members to be self-reinforcing about

high performance, to be self-critical of

low

performance,

to set explicit performance

goals, to evaluate goal

achievement, and to rehearse

different

performance

strategies before trying

them.

If

team members are to maintain

sufficient autonomy to control variance

from goal attainment, the

leader

may

need to help them manage

team boundaries. Where teams

have limited control over

their task

environment,

the leader may act as a

buffer to reduce environmental

uncertainty. This can include

mediating

and negotiating with other organizational

units, such as higher management, staff

experts, and

related

work teams. Research

suggests that better managers

spend more time in lateral

interfaces.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

These

new leadership roles require

new and different skills,

including knowledge of

sociotechnical

principles

and group dynamics, understanding of

both the task environment

and the team's technology,

and

ability

to intervene in the team to help members

increase their knowledge and

skills. Leaders of

self-

managed

teams also should have the

ability to counsel members

and to facilitate communication

among

them.

Many

managers have experienced

problems trying to fulfill the complex

demands of leading

self-managed

work

teams. The most typical

complaints mention ambiguity about

responsibilities and authority, lack

of

personal

and technical skills and

organizational support, insufficient attention

from higher management,

and

feelings of frustration in the

supervisory job.

Characteristics

of Self-managed Work

Teams:

Self-managed

work teams may be used

organization-wide, at a work site

composed of a number of work

teams,

or within just a few work

teams. But to whatever

degree they are used, there

are several

characteristics

that are common to all

self-managed work team

sites.

The

structure of the organization or work

site is based on team

concepts. There

are few managerial

levels

in the plant or work site

structure and few job

descriptions.

There

is an egalitarian culture and a noticeable

lack of status symbols. There

are no management

dinning

rooms, no assigned parking

places, and no special

furniture or d�cor for

manager's offices. There is

no

special dress code; if

uniforms are required, everyone,

including the plant superintendent wears

the

uniform.

A

work team has a physical

site. There

are functional boundaries

that members can

identify.

The

number of people in a team is kept as

small as possible. Typical

size range from five to

fifteen

members.

Work

teams order material and

equipment. They

set goals, profit targets,

and also rewards for the

team

members.

They have a voice in who is hired

and fired.

Team

members have a sense of vision

for their team and their

organization.

A

vision provides direction and

energizes team behavior to

accomplish goals.

There

is strong partnership between

team members and management.

If

there is a labor union, the

union is also a member of the

partnership.

Team

members are different enough.

Members

learn because of variety of viewpoints,

backgrounds,

cultural

experiences and

training.

Information

of all types is openly shared.

The

information system needs to be

well developed and

available

to all members. Members are

knowledgeable in accounting and

statistical concepts for

decision

making.

Team

members should be skilled and knowledgeable in

their areas. Team

members should have

good

interpersonal skills and a desire

and ability to work with

others.

Training,

and specially cross-training, is a major requirement

of self-managed teams. The

success

of

a team depends on its

members being skilled and knowledgeable

in a variety of areas, including

technical

skills,

finance and accounting,

competition in the marketplace, and

group process.

Team

managers are knowledgeable of

customers, competitors, and suppliers.

The

primary emphasis

is

to focus on customers. From the

team's standpoint, a customer is someone

within the organization or

external

to the organization that uses the team's

product/service.

Table of Contents:

- The Challenge for Organizations:The Growth and Relevance of OD

- OD: A Unique Change Strategy:OD consultants utilize a behavioral science base

- What an “ideal” effective, healthy organization would look like?:

- The Evolution of OD:Laboratory Training, Likert Scale, Scoring and analysis,

- The Evolution of OD:Participative Management, Quality of Work Life, Strategic Change

- The Organization Culture:Adjustment to Cultural Norms, Psychological Contracts

- The Nature of Planned Change:Lewin’s Change Model, Case Example: British Airways

- Action Research Model:Termination of the OD Effort, Phases not Steps

- General Model of Planned Change:Entering and Contracting, Magnitude of Change

- The Organization Development Practitioner:External and Internal Practitioners

- Creating a Climate for Change:The Stabilizer Style, The Analyzer Style

- OD Practitioner Skills and Activities:Consultant’s Abilities, Marginality

- Professional Values:Professional Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, Technical Ineptness

- Entering and Contracting:Clarifying the Organizational Issue, Selecting an OD Practitioner

- Diagnosing Organizations:The Process, The Performance Gap, The Interview Data

- Organization as Open Systems:Equifinality, Diagnosing Organizational Systems

- Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Methods for Collecting Data, Observations

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Sampling, The Analysis of Data

- Designing Interventions:Readiness for Change, Techno-structural Interventions

- Leading and Managing Change:Motivating Change, The Life Cycle of Resistance to Change

- Leading and managing change:Describing the Core Ideology, Commitment Planning

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Measurement

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Research Design

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Group Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Leadership and Authority, Group Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Third-Party Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Building, Team Building Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Management Styles

- Organization Process Approaches:Application Stages, Microcosm Groups

- Restructuring Organizations:Structural Design, Process-Based Structures

- Restructuring Organizations:Downsizing, Application Stages, Reengineering

- Employee Involvement:Parallel Structures, Multiple-level committees

- Employee Involvement:Quality Circles, Total Quality Management

- Work Design:The Engineering Approach, Individual Differences, Vertical Loading

- Performance Management:Goal Setting, Management by Objectives, Criticism of MBO

- Developing and Assisting Members:Career Stages, Career Planning, Job Pathing

- Developing and Assisting Members:Culture and Values, Employee Assistance Programs

- Organization and Environment Relationships:Environmental Dimensions, Administrative Responses

- Organization Transformation:Sharing the Vision, Three kinds of Interventions

- The Behavioral Approach:The Deep Assumptions Approach

- Seven Practices of Successful Organizations:Training, Sharing Information