|

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

36

Employee

Involvement

Changing

Michael Dell's DNA

Dell

Inc. is one of the world's largest PC

manufacturers, with a marketing and

manufacturing system that is

repeatedly

studies and copied. Of the

Fortune 500 companies, Dell

topped the list in 10-year

total return to

investors.

However, despite Dell's

success year after year,

Dell's CEO and founder,

Michael Dell, still

manages

with the urgency and

determination he had when he started the

company out of his college

dorm

some

20 years ago. "I still think

of us as a challenger. I still think of

us attacking," says

Dell.

But

not all is well in Camelot.

A recent survey of Dell's

employees revealed that half

of them would leave if

they

got the chance. Internal interviews of

the subordinates of Michael Dell

and the firm's president,

Kevin

Rollins,

revealed that they felt Dell

was impersonal and

emotionally detached, and Rollins,

autocratic and

antagonistic.

Michael

Dell believes that the

status quo is never good

enough. Once a problem is

uncovered, it should be

dealt

with quickly and directly.

In the 1990's, when the company was

rapidly growing, it recruited

seasoned

managers

from IBM and Intel. Some

quickly bailed out because they

were not willing to work in

Dell's

demanding

culture. An executive coach who

has worked with Michael

Dell since 1995 says,

"They need to

work

a lot on appreciating

people."

Michael

Dell, facing the results of the

employee surveys, took a

page out of his own

book. Fearing an

exodus

of talent and a tearing apart of the

company by antagonized employees,

Dell went before his

management

team and offered an honest

self-critique.

He

acknowledged that he was shy

and made him appear

removed and not

caring.

He

promised to build tighter relationship

with his team. Within

days, a videotape of meeting was

shown to

every

manager in the company.

Like

Dell, a growing number of today's

companies are not only

concerned but doing

something about the

way

they manage their employees. They

recognize that empowered

employees are the difference

between

success

and failure in the long run.

Faced with competitive

demands for lower costs,

higher performance

and

greater flexibility, organizations

are increasingly turning to

employee involvement (El) to

enhance the

participation,

commitment, and productivity of their

members.

Employee

involvement is a broad term that has

been variously referred to as

"empowerment"

"participative

management," "work design," "industrial

democracy," and "quality of

work life."

Empowerment

is giving employees power to make

decisions about work. Firms

that have transformed

their

culture

claim to have increased

productivity and number of clients,

made each employee feel a

sense of

ownership,

and increased profits. OD

interventions in this area are,

therefore, aimed at moving

decision

making

downward in the organization, closer to where the

actual work takes place,

i.e. delegation of power.

The

following major El applications are

discussed in this chapter: parallel

structures, including cooperative

union--management

projects and quality

circles; high- involvement

organizations; and total

quality

management.

Two additional El approaches,

work design and reward

system interventions, are

discussed in

Chapters

16 and 17,

respectively.

Employee

Involvement: What is it?

Employee

involvement is the current label used to

describe a set of practices

and philosophies that

started

with

the quality-of-work-life movement in the late

1950s. The phrase quality of

work life was used to

stress

the

prevailing poor quality of

life at the workplace. As described

earlier, both the term QWL and

the

meaning

attributed to it have undergone

considerable change and development. In

this section, we provide

a

working definition of EI, document the

growth of El practices in the United

States and abroad,

and

clarify

the Important and often

misunderstanding relationship between EI

and productivity.

A

Working Definition of Employee

involvement:

Employee

involvement seeks to increase

members input into decisions

that affect organization

performance

and employee well-being. It can be

described in terms of four

key elements that

promote

worker

involvement:

1.

Power: This

element of EI includes providing people

with enough authority to make

work-related

decisions

covering various issues such as

work methods, task

assignments, performance

outcomes,

customer

service, and employee

selection. The amount of power afforded

employees can vary enormously,

from

simply asking them for input

into decision that managers

subsequently make, to managers

and

workers

jointly

making

decisions,

to

employees

making

decisions

themselves.

2.

Information. Timely

access to relevant information is vital

to making effective decisions.

Originations

can

promote El by ensuring that the

necessary information flows freely to

those with decision

authority.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

This

can include data about operating results,

business plans, competitive conditions,

new technologies and

work

methods, and ideas for

organizational improvement.

3.

Knowledge and skills. Employee

involvement contributes to organizational

effectiveness only to the

extent

that employees have the

requisite skills and knowledge to

make good decisions. Organization

can

facilitate

El by providing training and development

programs for improving

members' knowledge and

skills.

Such learning can cover an

array of expertise having to do with

performing tacks, making

decisions,

solving

problems, and understanding how the

business operates.

4.

Rewards. Because

people generally do those things for

which they are recognized,

rewards can have a

powerful

effect on getting people. Involved in the organization

meaningful opportunities for

involvement

can

provide employees with

internal rewards, such as

feelings of self-worth and

accomplishment. External

rewards,

such as pay and promotions,

can reinforce El when they are linked

directly to perform

outcomes

that

result from participation in

decision making.

Those

four elements power information,

knowledge and skills, and

rewards contribute to El success

by

determining

how much employee

participation in decision making is

possible in organization. The

farther

that

all four elements are moved

downward throughout the organization, the greater the

employee

involvement.

Furthermore, because the four elements of

El are interdependent they must be

changed

together

to obtain positive results.

For example, if organization members

are given more power

and

authority

to make decisions but do not

have the information or knowledge and

skill to make good

decisions,

then the value of involvement is

likely to be negligible. Similarly, increasing

employees' power

information,

and knowledge and skills but

not linking rewards to the

performance consequences of

changes

gives

members little incentive to improve

organizational performance. The El

methods that will be

described

here vary in how much

involvement is afforded employees.

Parallel structures, such as

union-

management

cooperative efforts and quality

circles, are limited in the

degree that the four

elements of EI

are

moved downward in the organization; high-involvement

organizations and total

quality management

provide

far greater opportunities

for involvement.

How

Employee Involvement Affects

Productivity?

An

assumption underlying much of the El

literature is that such interventions

will lead to higher

productivity.

Although this premise has

been based mainly on anecdotal

evidence and a good deal

of

speculation,

there is now a growing body

of research findings to support

that linkage. Studies have

found a

consistent

relationship between El practices and

such productivity measures as financial

performance,

customer

satisfaction, labor hours,

and waste rates.

Attempts

to explain this positive linkage traditionally

have followed the idea that

giving people more

involvement

in work decisions raises

their job satisfaction and,

in turn, their productivity. There is

growing

evidence

that this satisfaction-

causes-productivity premise is too

simplistic and sometimes

wrong.

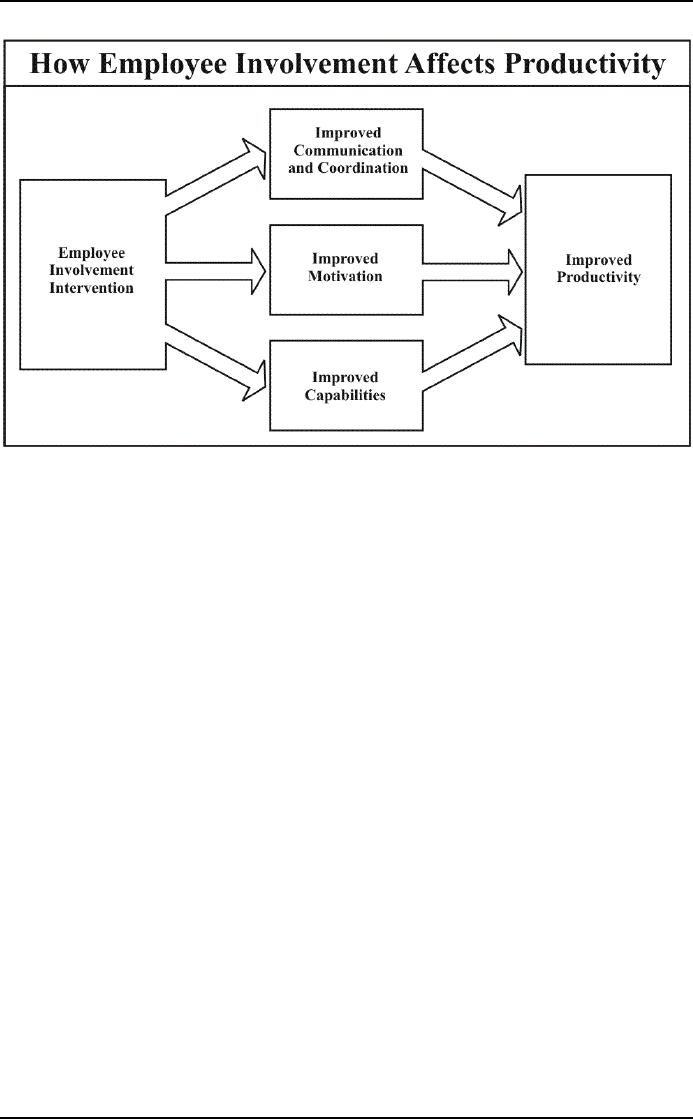

A

more realistic explanation for

how El interventions can affect

productivity is shown in Figure

47.El

practices,

such as participation in workplace

decisions, can improve

productivity in at least three

ways.

First, such

interventions can improve communication

and coordination among

employees and

organizational

departments and help

integrate the different jobs or

departments that contribute to

an

overall

task.

Second, El

interventions can improve

employee motivation, particularly when they

satisfy important

individual

needs. Motivation is translated

into improved performance

when people have the necessary

skills

and

knowledge to perform well and when the

technology and work situation

allow people to affect

productivity.

For example, some jobs

are so rigidly controlled

and specified that

individual motivation

can

have

little impact on

productivity.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Figure

47

Third, EI

practices can improve the

capabilities of employees, thus enabling

them to perform better.

For

example,

attempts to increase employee

participation in decision making

generally include skill training

in

group

problem solving and communication.

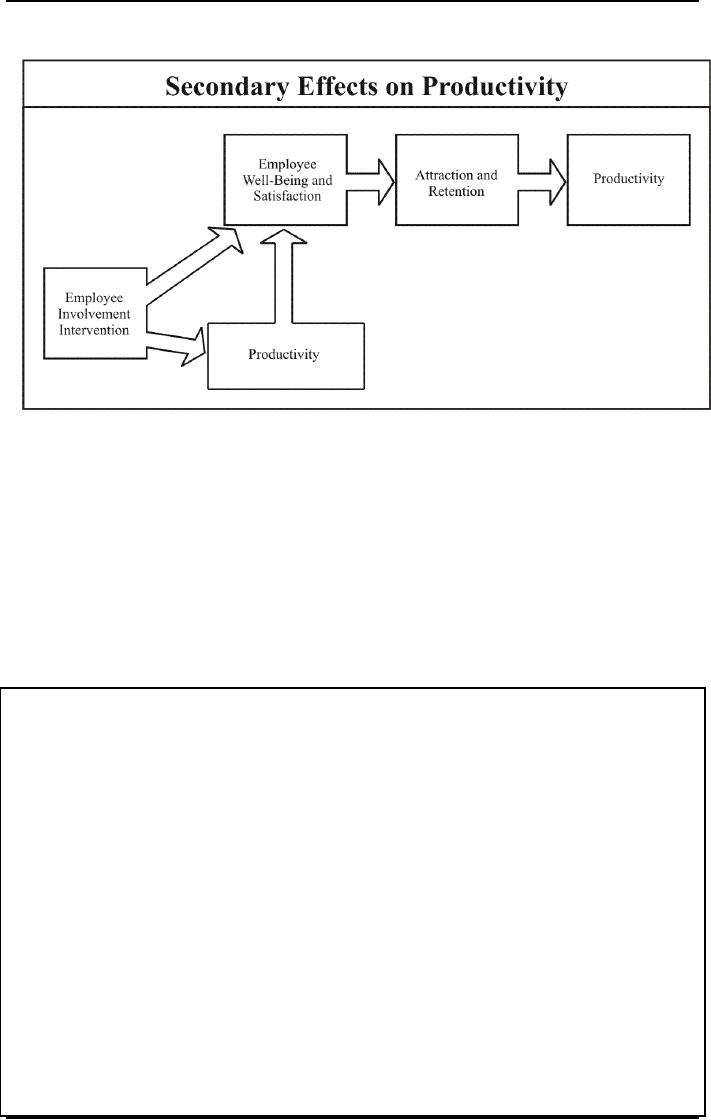

Figure

48 shows the secondary effects of

EI. These practices increase

employee well-being and

satisfaction

by

providing a better work environment

and a more fulfilling job.

Improved productivity also

can increase

satisfaction,

particularly when it leads to greater

rewards. Increased employee

satisfaction, deriving from

EI

interventions

and increased productivity

ultimately can have a still

greater impact on productivity

by

attracting

good employees in join and

remain with the organization.

In

sum, El interventions are

expected to increase productivity by

improving communication and

coordination

employee motivation, and

individual capabilities. They also

can influence productivity by

means

of the secondary effects of increased

employee well-being and satisfaction.

Although a growing

body

of

research supports these

relationships, there is considerable

debate over the strength of the

association

between

El and productivity. Recent

data support the conclusion

that relatively modest levels of

Ph

produce

moderate improvements in performance and

satisfaction and those higher

levels of El produce

correspondingly

higher levels of performance.

Employee

Involvement Application:

This

section describes three major El

applications that vary in the amount of power,

information,

Knowledge

and skills, and rewards

that are moved downward through the

organization (from least to

most

involvement):

parallel structures, including cooperative

projects and quality

circles; high-Involvement

organizations

and total quality

management.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Figure

48

Parallel

Structures:

Parallel

structures involve members in resolving

ill-defined, complex problems and

build adaptability

into

bureaucratic

organizations. Also known as

"collateral structures," "dualistic

structures,' or "shadow

structures,"

parallel structures operate in

conjunction with the formal organization.

They provide members

with

an alternative setting in which to

address problems and to

propose innovative solutions free

from the

formal

organization structure and culture. For

example, members may attend

periodic off-site meetings

to

explore

ways to improve quality in

their work area or they may

be temporarily assigned to a special

project

or

facility to devise new

products or solutions to organizational problems.

Parallel structures facilitate

problem

solving and change by providing time

and resources for members to

think, talk, and act

in

completely

new ways. Consequently,

norms and procedures for

working in parallel structures are

entirely

different

from those of the formal organization.

This section describes the application

steps associated with

most

parallel structures; discusses two

specific applications cooperative union-management

projects and

quality

circles; and reviews the

research on their

effectiveness.

OD

in Practice: A Work-out Meeting at

General Electric Medical System

Business

As

part of the large-scale change

effort, Jack Welch and

several managers at General Electric

devised a

method

for involving many organization

members in the change process.

Work-Out is a process

for

gathering

the relevant people to discuss important

issues and develop a clear action plan.

The program has

four

goals to use employees' knowledge

and energy to improve work,

to eliminate unnecessary work, to

build

trust through a process that

allows and encourages

employees to speak out

without being fearful,

and

to

engage in the construction of an organization that is

ready to deal with the

future.

At

GE Medical Systems (GEMS),

internal consultants conducted

extensive interviews with

managers

throughout the organization. The interviews

revealed considerable dissatisfaction

with existing

systems,

including performance management

(too many measurement

processes, not enough focus

on

customers,

unfair reward systems, and

unrealistic goals), career development,

and organizational climate.

Managers

were quoted as saying:

I'm

frustrated. I simply can't do the quality of

work that I want to do and

know how to do. I

feel

my hands are tied. I have no time. I

need help on how to delegate

and operate in this new

culture.

The

goal of downsizing and delaying is

correct. The execution

stinks.

The

concept is to drop a lot of

`less important" work. This

just didn't happen. We still

have to know all the

details,

still have to follow all the

old policies and

systems.

In

addition to the interviews, Jack Welch

spent some time at GEMS

headquarters listening and trying

to

understand

the issues facing the

organization.

Based

on the information compiled, about fifty

GEMS employees and managers

gathered for a

five-day

Work-Out

session. The participants included the

group executive who oversaw

the GEMS business,

his

staff,

employee relations managers, and

informal leaders from the

key functional areas who

were thought to

be

risk takers and who would

challenge the status quo. Most of the

work during the week was

spent

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

unraveling,

evaluating, and reconsidering the

structures and processes

that governed work at GEMS.

Teams

of

managers and employees

addressed business problems.

Functional groups developed visions of

where

their

operations were headed. An important

part of the teams' work was

to engage in "bureaucracy

busting"

by identifying CRAP (Critical Review

Appraisals) in the organization. Groups

were asked to list

needless

approvals, policies, meetings,

and reports that stifled

productivity. In an effort to increase

the

intensity

of the work and to encourage

free thinking, senior

managers were not a part of

these discussions.

At

the end of the week, the senior

management team listened to the

concerns, proposals,

and

action

plans from the different

teams. During the presentations,

senior GEMS managers worked

hard to

understand

the issues, communicate with the

organization members, and build trust by

sharing

information,

constraints, and opportunities.

Most of the proposals focused on

ways to reorganize work

and

improve

returns to the organization. According to

traditional Work-Out methods,

managers must make

instant,

on-the-spot decisions about each idea in

front of the whole group. The

three decision choices

are

approval;

rejection with clear reasons;

and need more data,

with a decision to be made

within a month.

The

five-day GEMS session ended

with individuals and

functional teams signing

close to one

hundred

written contracts to implement the new

processes and procedures or

drop unnecessary work.

The

contracts

were between people, between

functional groups, and

between levels of management,

and

organizational

contracts affecting all members. One

important outcome of the Work-Out

effort at GEMS

was

a decision to involve suppliers in

its internal email network.

Through that interaction, GEMS

and a key

supplier

eventually agreed to build new-product prototypes

together, and their joint

efforts have led to

further

identification of ways to reduce

costs, improve design

quality, or decrease cycle

times.

Work-Out

at GE has been very successful

but hard to measure in

dollar terms. Since

1988,

hundreds

of Work-Outs have been held,

and the concept has

continued to evolve into best

practice

investigations,

process mapping, and change-acceleration

programs. The Work-Out

process, however,

clearly

is based on the confrontation meeting

model, where a large group of people

gathers to identify

issues

and plan actions to address

problems.

Application

Stages:

Parallel

structures fall at the lower

end of the EI scale. Member

participation typically is restricted

to

making

proposals and to offering

suggestions for change

because subsequent decisions

about implementing

the

proposals are reserved for

management. Membership in parallel structures

also tends to be

limited,

primarily

to volunteers and to numbers of employees

for which there are

adequate resources.

Management

heavily

influences the conditions under which parallel

structures operate. it controls the amount

of

authority

that members have in making

recommendations, the amount of information

that is shared with

them,

the amount of training they receive to

increase their knowledge and

skills, and the amount of

monetary

rewards for participation.

Because parallel structures offer

limited amounts of EI, they

are most

appropriate

for organizations with

little or no history of employee

participation top-down

management

styles

and bureaucratic cultures.

Parallel structures typically

are implemented in the following

steps:

1.

Define

the purpose and scope. This

first step involves defining the

purpose for the parallel

structure

and

initial expectations about how it

will function. Organizational diagnosis

can help clarify which

specific

problems

and issues to address, such

as productivity, absenteeism, or service

quality. In addition,

management

training in the use of parallel

structures can include discussions about

the commitment and

resources

necessary to implement them; the openness

needed to examine organizational

practices,

operations,

and

policies;

and

the

willingness

to

experiment

and

learn.

2.

Form

a steering committee. Parallel

structures typically use a

steering committee composed

of

acknowledged

leaders of the various functions

and constituencies within the

formal organization. This

committee

performs the following tasks:

�

Refining

the scope and purpose of the parallel

structure

�

Developing

a vision for the

effort

�

Guiding

the creation and implementation of the

structure

�

Establishing

the linkage mechanisms between the parallel

structure and the formal

organization

�

Creating

problem-solving groups and

activities

�

Ensuring the

support of senior

management

OD

practitioners can play an important role

in forming the steering committee. First,

they can help develop

and

maintain group norms of learning and

innovation. These norms set

the tone for problem

solving

throughout

the parallel structure, second, they can

help the committee create a

vision statement that

refines

the

structures purpose and

promotes ownership of it. Third, they

can help Committee members

develop

and

specify objectives and

strategies, organizational expectations

and required resources, and

potential

rewards

for participation in the parallel

structure.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

3.

Communicate

with organization members. The

effectiveness of a parallel structure

depends on a

high

level of involvement from organization

members, and Communicating the purpose,

procedures, and

rewards

of participation can promote

that involvement. Moreover,

employee participation in developing

a

structure's

vision and purpose can

increase ownership and visibly

demonstrate the "new way" of

working.

Continued

communication concerning parallel structure

activities can ensure member

awareness.

4.

Form employee problem-solving groups.

These

groups are the primary means of

accomplishing the

purpose

of the parallel learning structure. Their

formation involves selecting and

training group

members,

identifying

problems for the groups to

work on, and providing

appropriate facilitation. Selecting

group

members

is important because success

often is a function of group

membership. Members need

to

represent

the appropriate hierarchical levels,

expertise, functions, and constituencies

that are relevant to the

problems

at hand. This allows the parallel

structure to identify and

communicate with the formal

structure.

It

also provides the necessary resources to

solve the problems.

Once

formed, the groups need appropriate

training. This may include

discussions about the vision of

the

parallel

structure, the specific problems to he

addressed, and the way those

problems will he solved, As

in

the

steering committee, group

norms promoting openness,

creativity, and integration

need to be

established.

Another key resource

for parallel structures is

facilitation for the

problem-

solving

groups. Although this can be

expensive, it can yield

important benefits in

problem-solving

efficiency

and quality. Group members

are being asked to solve

problems by cutting through

traditional

hierarchical

and functional boundaries. Facilitators

can pay special attention to

processes that require

disparate

groups to cooperate. They

can help members identify

and resolve prob1em-solving issues

within

and

between groups.

5.

Address

the problems and issues. Generally,

groups in parallel structures solve

problems by using an

action

research process. They diagnose

specific problems, plan appropriate

solutions and impalement and

evaluate

them. Problem solving can be facilitated

when the groups and the

steering committee

relate

effectively

to each other. This permits

the steering committee to direct

problem-solving efforts in an

appropriate

manner, to acquire the necessary

resources and support, and to approve

action plans. It also

helps

ensure that the groups' solutions are

linked appropriately to the formal

organization. In this manner,

early

attempts at change will have

a better chance of succeeding.

6.

Implement

and evaluate the changes.

This

step involves implementing appropriate

organizational

changes

and assessing the results.

Change proposals need the

support of the steering committee

and the

formal

authority structure. As changes

are implemented, the organization needs

information about their

effects.

This lets members know

how successful the changes

have been and if they need

to be modified. In

addition,

feedback on changes helps the

organization learns to adapt and

innovate.

Cooperative

Union-Management Projects:

Cooperative

union-management projects are

one of the oldest El applications of parallel

structures. They

are

associated with the original

QWL movement and its focus

on workplace change, although more

recent

approaches

have broadened that focus to

include productivity improvement. Cooperative

union-

management

projects are relatively new to OD in the

United States, but such dual

involvement has a

long

history

in other countries, particularly the

Scandinavian countries. These

interventions tend to have

the

following

structural characteristics:

Steering

committee. This

top-level labor-management committee

serves as the basic center

for planning.

It

is created during the project start-up

phase and comprises key

representatives from management,

such as

a

president or chief operating officer, and

each of the unions and employee

groups involved in the project,

such

as local union presidents.

The steering committee's

mandate is to begin activities directed

at

improving

both the quality of working

life and the effectiveness of the

organization. Members are

encouraged

to be open about the need for improvements in

productivity. Unionists are

told that because

projects

are jointly controlled

efforts, they need not fear

an organization's productivity motives.

Indeed,

many

unions distrust a management philosophy

that does not express

concern for higher productivity

or

the

quality of its product or

service.

Multiple-level

committees. Because

the steering committee may

not be able to oversee all

aspects of a

project,

it often is necessary to establish

more than one

labor-management committee at a number

of

selected

levels in the organization to reflect the differing

interests and knowledge. For

example, the steering

committee

can be amplified and

assisted by working committees at the

plant, department, and

shop-floor

levels.

These lower-level committees deal

with day- to-day project

activities.

Ad

hoc committees. In

many instances, labor-management

committees initiate particular projects

that

involve

the workers and managers in a

specific part of the organization. At the

same time, employees

themselves

frequently initiate action toward a

particular goal. In such cases, an ad

hoc committee is

established

to bring about change. Such

committees are charged with

a specific task and have a

limited

lifetime.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

External

consultants. External

change agents act as

third-party facilitators, offering

guidance and

assistance

to the labor-management committees and

prob1em-solving and teamwork training for

all

participants.

In most projects, the steering

committee selects the

consultants.

External

researchers. In

some projects, researchers

are brought in to assess the

overall results of

the

intervention.

In those cases, separate

roles for the change agents

and the evaluation researchers are

created.

It

is assumed that keeping these

functions separate enables

consultants to be concerned with

client needs

and

researchers to do a more objective

assessment of the intervention.

Excellent

descriptions of cooperative union-management

projects are available in the literature,

featuring

longitudinal

discussions of problems, successes,

and partial failures. The

projects include a large

metropolitan

hospital, a large international company

called the "National Processing

Case," and the

Bolivar

plant

of Harman International Industries. Union-management

cooperative projects have been

carried out in

most

industrial and public

sectors in the United States.

Both managers and unionists

realize that their

fates

are

positively correlated and

that both parties must be

jointly involved in enhancing the

quality of work life

and

productivity. Almost every major

union and corporation has

become involved in these

efforts,

including

UAW, Communications Workers of

America, Ford, General Motors,

and AT&T.24

Application

7 presents an example of a cooperative

union--management program at GTE

of

California.

Application

7: Union-Management Cooperation at GTE

California

GTE

of California (GTEC) and the

Communications Workers of America

embarked on a cooperative

union--management

project during the fall of

1984. This OD effort was in

response to the court-ordered

breakup

of AT&T, which forced firms in the

telecommunications industry to rethink the

way that they

conducted

business. Over time, the deregulation of the industry

would remove the protective

shield of

guaranteed

returns on investment, monopoly territories,

and "cradle-to-grave" employment that

had

characterized

operations.

Under

the new conditions, GTEC management

and union leadership believed strongly

that the company's

usual

way of operating in the regulatory environment

would need to change. The

traditional approach to

managing

the business was characterized by

centralized decision making and

work planning,

lackadaisical

service

orientation, and little

cross- functional teamwork. The advent of

deregulation was coupled with

tremendous

technological changes in information

processing and service delivery

and a broadening of the

belief

that workers should have

more say in decisions that

affect them. The old way of

managing produced

low

morale and mediocre service

in this changing environment.

Consequently, management and

union

officials

felt the need for improved

adaptability and productivity and a

more customer-oriented

workforce.

For

some time, union leadership

had been researching worker

participation and

union--management

cooperation

at its national office in Washington,

D.C. This research was

limited, however, because no

one

had

implemented such interventions during a

period of rapid deregulation. At the same

time, GTEC senior

management

had been meeting with

other telephone companies to discuss

how to meet the

challenges

posed

by deregulation, technological change, and

increased worker sophistication. These

discussions

consistently

pointed out that effective

organizations in deregulated environments

were more

decentralized

in

their decision making. But, given

decades of regulatory tradition, the

means to accomplish such

an

organizational

change were not

clear.

Working

with OD consultants from the

University of Southern California's Center

for Effective

Organizations,

senior managers and union

leaders began discussing how

to increase worker

participation

and

decentralize decision making without

treading on traditional collective bargaining issues.

These

discussions

resulted in a cooperative union--management

partnership called Employee Involvement.

The

purpose

of the El process was to improve

employees' quality of working

life and productivity. The

group

of

senior managers and union

officials became the steering

committee for the project

and developed a

vision

of the El process and its

objectives.

The

steering committee established a parallel

structure to guide implementation of the

El process with the

twenty-six

thousand employees at GTEC. It

comprised three area

coordinating committees responsible

for

implementing

the El process in their respective

geographic regions. Each

coordinating Committee created

support

committees for the functional

areas in its region. The support

committees, in turn, established

El

teams

that would identify and

solve work-related problems in the

different units of the company.

Each

committee

and team was staffed

with both union and

management personnel as

appropriate.

As

part of the early implementation

activities, all organization members

attended a two-hour

orientation

meeting that described the

goals, structure, and

implementation of the El process.

This

orientation

was conducted by both GTEC

management and local union

presidents. In addition, a three-

day

union--management training program was

conducted for all

supervisors and union

officials (local

presidents

and stewards). During the

first two days of training,

union leaders and GTEC

managers were

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

trained

separately in their respective

roles and responsibilities in the El

process. On the third day,

the

managers

and union officials were

brought together to discuss how the

implementation of El would

proceed

in their particular departments. Members

of the support committees and

employee involvement

teams

attended a five-day training program

focusing on meeting-management skills,

problem- solving

techniques,

and group dynamics. They

were also provided with

internal facilitators if needed.

Over

the next several months, the El

teams focused on quality-of-work-life

issues, such as the provision

of

bottled

drinking water, rather than on

productivity-related changes. Responsible

Committees were

concerned

about this limited focus and

modified the process to align it more

closely with El's

productivity

objectives.

For example, the problem-solving

training was changed to

emphasize performance issues.

In

addition,

the composition and responsibilities of the different

committees were revised to

increase senior

management

and union leadership

involvement and accountability. At the organizational

level, a new

incentive

compensation system was

initiated. This system rewarded

cross-functional teamwork and

generated

many ideas for employee

involvement. Finally, facilitators were

assigned permanently to

functional

areas to focus on operating

problems.

The

El process produced many successes. One

team, established in early

985, worked for more

than two

years

to simplify the way field

employees reported their time at work.

These efforts produced savings

of

more

than $3 million by increasing the amount

of productive time that employees

spent in the field and

by

consolidating

several offices that had

been used to collect,

collate, and report

work-time Information.

Between

1987 and 988, an evaluation of the El

process concluded that the program

had produced a net

savings

(after the costs of training and

dedicated personnel) of more

than $1 million. In 1991,

GTEC

surpassed

its competition in measures of

customer satisfaction for

large- and medium-sized

businesses to

become

the benchmark for others. In

addition, several cost

measures also decreased

significantly. The El

program

survived through two union contract

negotiations and massive corporate

changes that reduced

the

size

of the work force by consolidating work

functions and business units

and standardizing systems

and

equipment.

Table of Contents:

- The Challenge for Organizations:The Growth and Relevance of OD

- OD: A Unique Change Strategy:OD consultants utilize a behavioral science base

- What an “ideal” effective, healthy organization would look like?:

- The Evolution of OD:Laboratory Training, Likert Scale, Scoring and analysis,

- The Evolution of OD:Participative Management, Quality of Work Life, Strategic Change

- The Organization Culture:Adjustment to Cultural Norms, Psychological Contracts

- The Nature of Planned Change:Lewin’s Change Model, Case Example: British Airways

- Action Research Model:Termination of the OD Effort, Phases not Steps

- General Model of Planned Change:Entering and Contracting, Magnitude of Change

- The Organization Development Practitioner:External and Internal Practitioners

- Creating a Climate for Change:The Stabilizer Style, The Analyzer Style

- OD Practitioner Skills and Activities:Consultant’s Abilities, Marginality

- Professional Values:Professional Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, Technical Ineptness

- Entering and Contracting:Clarifying the Organizational Issue, Selecting an OD Practitioner

- Diagnosing Organizations:The Process, The Performance Gap, The Interview Data

- Organization as Open Systems:Equifinality, Diagnosing Organizational Systems

- Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Methods for Collecting Data, Observations

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Sampling, The Analysis of Data

- Designing Interventions:Readiness for Change, Techno-structural Interventions

- Leading and Managing Change:Motivating Change, The Life Cycle of Resistance to Change

- Leading and managing change:Describing the Core Ideology, Commitment Planning

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Measurement

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Research Design

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Group Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Leadership and Authority, Group Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Third-Party Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Building, Team Building Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Management Styles

- Organization Process Approaches:Application Stages, Microcosm Groups

- Restructuring Organizations:Structural Design, Process-Based Structures

- Restructuring Organizations:Downsizing, Application Stages, Reengineering

- Employee Involvement:Parallel Structures, Multiple-level committees

- Employee Involvement:Quality Circles, Total Quality Management

- Work Design:The Engineering Approach, Individual Differences, Vertical Loading

- Performance Management:Goal Setting, Management by Objectives, Criticism of MBO

- Developing and Assisting Members:Career Stages, Career Planning, Job Pathing

- Developing and Assisting Members:Culture and Values, Employee Assistance Programs

- Organization and Environment Relationships:Environmental Dimensions, Administrative Responses

- Organization Transformation:Sharing the Vision, Three kinds of Interventions

- The Behavioral Approach:The Deep Assumptions Approach

- Seven Practices of Successful Organizations:Training, Sharing Information