|

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

35

Restructuring

Organizations

Network-Based

Structures:

A

network-based structure manages the

diverse, complex, and

dynamic relationships among

multiple

organizations

or unit5, each specializing in a

particular business junction or task.

Sonic contusion over the

definition

of a network has been clarified

recently by a typology describing

four basic types of

networks.

·

An

internal market network

exists when a single organization

establishes each subunit as an

independent

profit center that is allowed to

buy and sell services

and resources from each

other as

well

as from the external market. Asea

Brown Boveri's (ABB) fifty

worldwide businesses consist

of

twelve

hundred companies organized

into forty-five hundred

profit centers that conduct

business

with

each other.

·

A vertical

market network is composed of

multiple organizations linked to a focal

organization that

coordinates

the movement of resources from raw

materials to end consumer.

Nike, for example,

has

its shoes manufactured in

different plants and then

organizes their distribution

through retail

outlets.

·

An

inter-market network represents alliances

among a variety of organizations in

different markets

and

is exemplified by the Japanese keiretsu

and the Korean

chaebol.

·

An

opportunity network is the most

advanced form of network

structure. It is a temporary

constellation

of

organizations

brought

together

to

pursue

a

single

purpose.

Once accomplished, the network

disbands.

These

types of networks can be distinguished

from one another in terms of whether they

are single or

multiple

organizations, single or multiple

industry, and stable or temporary.

For example, an internal

market

network

is a stable, single-organization, single-industry

structure; an opportunity network is a

temporary,

multiple-organization

structure that can span

several different

industries.

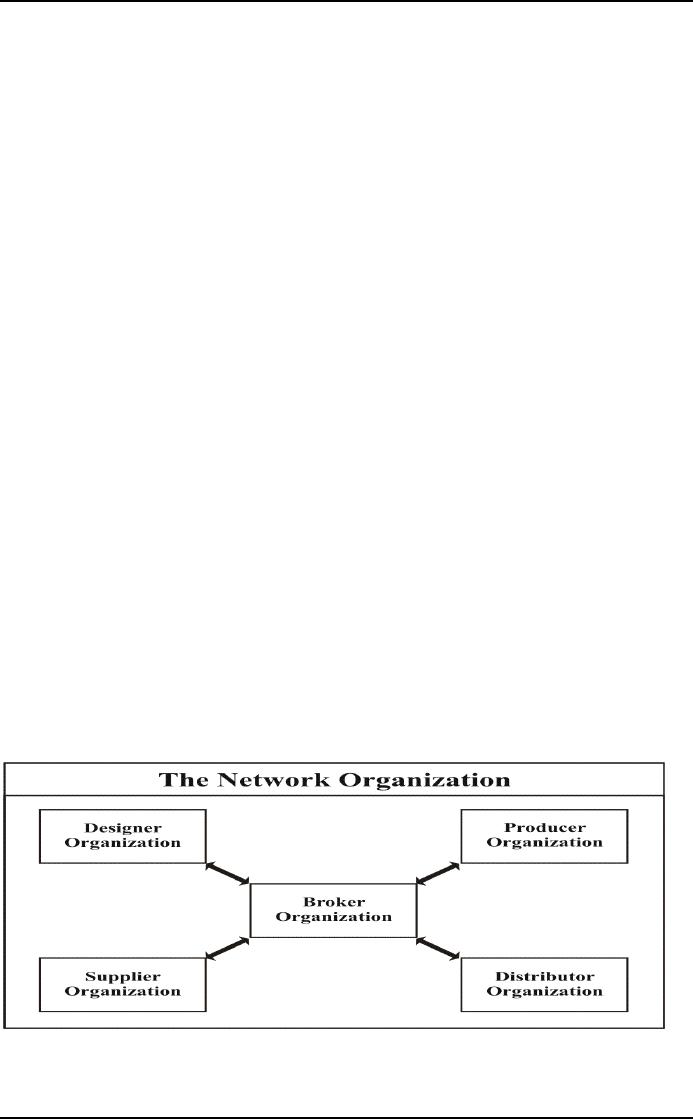

As

shown in Figure 46, the network

structure redraws organizational

boundaries and links

separate business

units

to facilitate task interaction. The

essence of networks is the relationships among

organizations that

perform

different aspects of work. In this

way, organizations do the things that

they do well; for example,

manufacturing

expertise is applied to production, and

logistical expertise is applied to distribution.

Network

organizations

use strategic alliances,

joint ventures, research and

development consortia, licensing

agreements,

and wholly owned subsidiaries to

design, manufacture, and

market advanced products,

enter

new

international markets, and develop

new technologies.

Network-based

structures are known by a variety of

names, including shamrock

organizations and

virtual,

modular,

or cellular corporations. Less formally, they

have been described as

"pizza" structures,

spider

webs,

starbursts, and cluster

organizations. Companies such as

Apple Computer, Benetton,

Sun

Microsystems,

Liz Claiborne, MCI WorldCom, and Merck

have implemented fairly sophisticated

vertical

market

and inter-market network structures.

Opportunity networks also are

commonplace in the

construction,

fashion, and entertainment industries, as

well as in the public

sector.

Figure

46: The Network

Organization

Network

structures typically have the

following characteristics.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

·

Vertical

desegregation. This

refers to the breaking up of the organization's

business functions, such

as

production, marketing, and distribution,

into separate organizations

performing specialized work.

In

the

film industry, for example,

separate organizations providing

transportation, cinematography,

special

effects,

set design, music, actors,

and catering all work

together under a broker organization, the

studio.

The

particular organizations making up the opportunity

network represent au important

factor in

determining

its success.'" More recently,

disintermediation, or the replacement of whole

steps in the

value

chain by information technology,

specifically the Internet, has fueled the

development and

numbers

of network structures.

·

Brokers.

Networks

often arc' managed by broker

organizations that locate

and assemble member

organizations.

The broker may play a

central role and subcontract

for needed products or services, or

it

may

specialize in linking equal

partners into a network. In the

construction industry, the general

contractor

typically assembles and

manages drywall, mechanical, electrical,

plumbing, and other

specialties

to erect a building.

·

Coordinating

mechanisms. Network

organizations generally are

not controlled by

hierarchical

arrangements

or plans. Rather, coordination of the

work in a network falls into

three categories:

informal

relationships, contracts, and

market mechanism. First, coordination

patterns can depend

heavily

on interpersonal relationships among individuals

who have a well-developed

partnership.

Conflicts

are resolved through reciprocity;

network members recognize

that each likely will

have to

compromise

at some point. Trust is

built anti nurtured over

time by these reciprocal

arrangements.

Second,

coordination can be achieved

through formal contracts,

such as ownership control,

licensing

arrangements,

or purchase agreements. Finally,

market mechanisms, such as

spot payments,

performance

accountability, and information systems,

ensure that all parties

are aware of each

others'

activities.

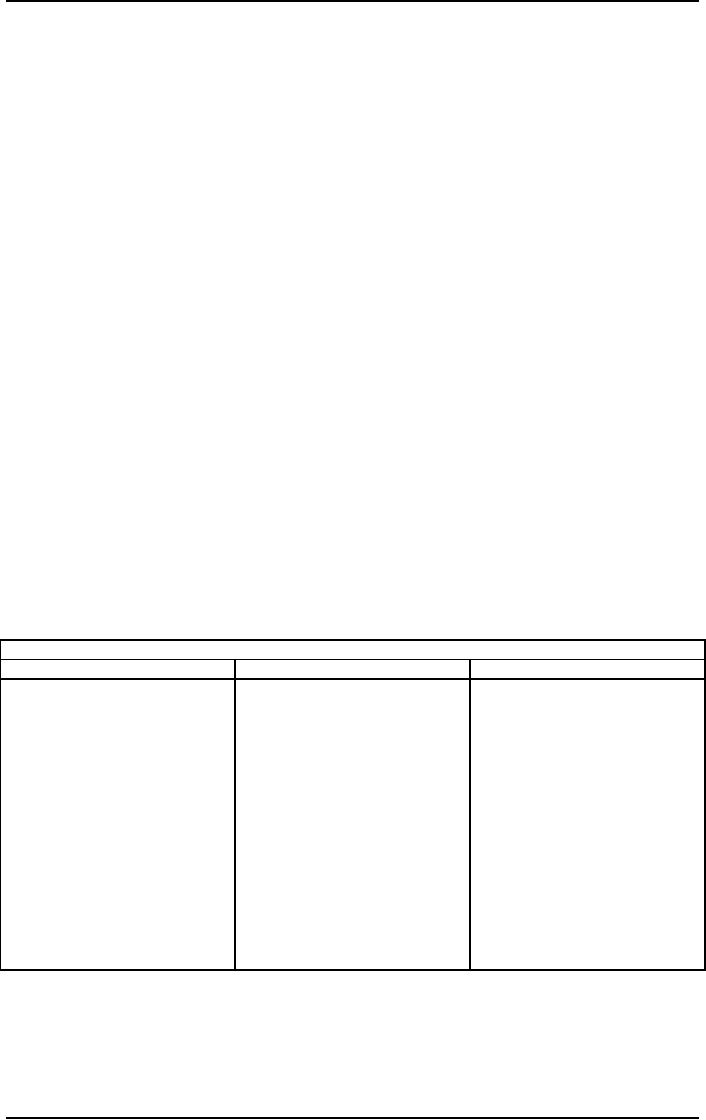

Network

structures have a number

of advantages and

disadvantages, as

shown

in

Table 16. They are highly

flexible and adaptable to

changing conditions. The ability to

form partnerships

with

different organizations permits the

creation of a "best-of-the-best" company to

exploit opportunities,

often

global in nature. They enable

each member to exploit its

distinctive competence. They

can

accumulate

and apply sufficient resources

and expertise to large, complex

tasks that single

organizations

cannot

perform. Perhaps most

important, network organizations

can have synergistic effects

whereby

members

build on each other's strengths

and competencies, creating a

whole that exceeds the sum

of its

parts.

Table

16

Advantages,

Disadvantages and Contingencies of the

Network-Based Form

Advantages

Disadvantages

Contingencies

·

Managing

lateral relations

·

Highly

complex and

·

Enables

highly flexible

and

adaptive response to

across

autonomous

uncertain

environments

·

Organizations

of all sizes

organizations

is difficult

dynamic

environments

·

Motivating

members to

·

Creates

a "best-of-the-

·

Goals

of organizational

best"

organization to

relinquish

autonomy to

specialization

and

focus

resources

on

join

the network is

innovation

troublesome

customer

and market

·

Highly

uncertain

·

Sustaining

membership

needs

technologies

·

and

benefits can be

Enables

each

·

Worldwide

operations

problematic

organization

to leverage a

·

May

give partners access

distinctive

competency

·

to

proprietary

Permits

rapid global

knowledge/technology

expansion

·

Can

produce synergistic

results

The

major problems with network

organizations are in managing

such complex structures. Galbraith

and

Kazanjian

describe network structures as

matrix organizations extending beyond the

boundaries of single

firms

but lacking the ability to appeal to a

higher authority to resolve conflicts.

Thus, matrix skills

of

managing

lateral relations across organizational

boundaries arc critical to administering

network structures.

Most

organizations, because they are

managed hierarchically, can be expected

to have difficulties

managing

lateral

relations. Other disadvantages of

network organizations include the

difficulties of motivating

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

organizations

to join such structures and

of sustaining commitment over time.

Potential members may

not

want

to give up their autonomy to link with

other organizations and,

once linked, they may have

problems

sustaining

the benefits of joining together. This is

especially true if time network

consists of organizations

that

are not the "best of breed."

Finally, joining a network

may expose the organization's

proprietary

knowledge

and skills to others.

As

shown in Table 16, network

organizations are best

suited to highly complex and uncertain

environments

where

multiple competencies and

flexible responses are

needed. They seem to apply to

organizations of all

sizes,

and they deal with complex

tasks or problems involving

high interdependencies across

organizations.

Network

structures fit with goals

that emphasize organization

specialization and

innovation.

Downsizing:

Downsizing

refers to interventions aimed at

reducing the site of the organization. This

typically is

accomplished

by decreasing the number of employees

through layoffs, attrition, redeployment, or

early

retirement

or by reducing the number of organizational units or

managerial levels through

divestiture,

outsourcing,

reorganization, or delayering. In practice, downsizing

generally involves layoffs where a

certain

number

or class of organization members is no longer

employed by the organizations.

Although

traditionally

associated with lower-level workers,

downsizing increasingly has claimed the

jobs of staff

specialists,

middle managers, and senior

executives.

An

important consequence of downsizing has

been the rise of the contingent

workforce. These less

expensive

temporary or permanent part-time workers

often are hired by the

organizations that just laid

elf

thousands

of employees. A study by the American

Management Association found that

nearly a third of the

720

firms in the sample had rehired recently

terminated employees as independent contractors

or

consultants

because time downsizings had

not been matched by an appropriate

reduction in or redesign of

the

workload. Overall cost

reduction was achieved by

replacing expensive permanent

workers with a

contingent

workforce.

Downsizing

is generally a response to at least

four major conditions. First, it is associated

increasingly with

mergers

and acquisitions. One in nine

job cuts during 1998

were the result of the integration of

two

organizations;

second, it can result from

organization decline caused by loss of

revenues and market

share

and

b1 technological and industrial change.

In southern California, an economy

traditionally dependent on

the

defense industry, more than

one hundred thousand jobs

have been lost to relocation or

elimination as

that

industry has contracted and

consolidated. Third, downsizing can

occur when organizations implement

one

of the new organizational structures

described above. For

example, creation of network-

based

structures

often involves outsourcing work to

other firms that is not

essential to the organization's

core

competence.

Fourth, downsizing can result

from beliefs and social

pressures that smaller are

better. In the

United

States; there is strong

conviction that organizations should be

leaner and more flexible.

Hamel and

Prahalad

warned, however, that organizations

must be careful that downsizing is

not a symptom,

"corporate

anorexia." Organizations may downsize

for their own sake

and not think about future

growth.

They

may lose key employees

who are necessary for

future success, cutting into

the organization's core

competencies

and leaving a legacy of mistrust

among members. In such

situations, it is questionable

whether

downsizing is developmental as defined in

OD.

Application

Stages:

Successful

downsizing interventions tend to proceed

by the following steps:

1.

Clarify

the organization's strategy. As a

first step, organization leaders

specify corporate strategy

arid

communicate clearly how downsizing

relates to it. They seek to

inform members that

downsizing

is not a goal h itself, hut a

restructuring process for achieving

strategic' objectives.

Leaders

need to provide visible and

consistent support throughout the

process. They can

provide

opportunities

for members to voice their

concerns, ask questions, and

obtain counseling if

necessary.

2.

Assess

downsizing options and make relevant

choices. Once

corporate strategy is clear, the

full

range of downsizing options can he

identified and assessed.

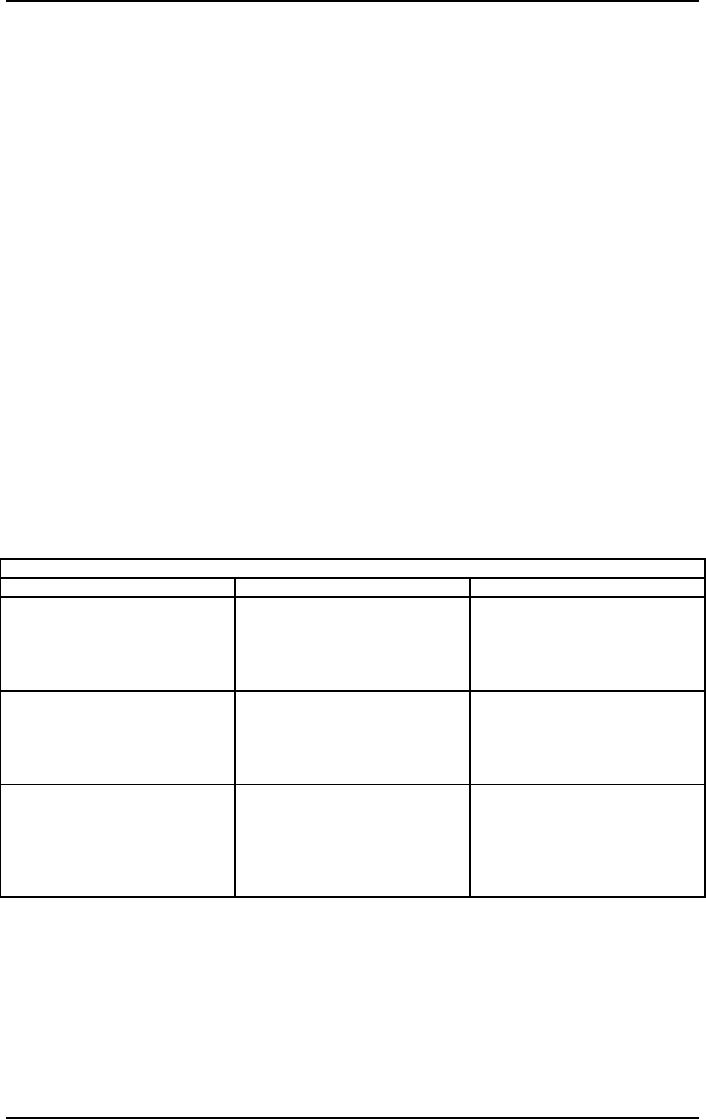

Table 17 describes three

primary

downsizing

methods: workforce reduction, organization

redesign, and systemic

change. A specific

downsizing

strategy may Use elements of

all three approaches.

Workforce reduction is aimed

at

reducing

the number of employees, usually in a relatively short

timeframe. It can include

attrition,

retirement

incentives, outplacement services,

and layoffs. Organization redesign attempt

to

restructure

the firm to prepare it for the

next stage of growth. This is a

medium term approach

that

can

be accomplished by merging organizational units,

eliminating management layers,

and

redesigning

tasks. Systemic change is a longer-term

option aimed at changing the culture

and

strategic

orientation of the organization. It can

involve interventions that alter the

responsibilities

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

and

work behaviors of everyone in the

organization and that promote

continual improvement as a

way

of life in the firm.

Case,

a manufacturer of heavy construction equipment,

used a variety of methods to

downsize,

including

eliminating money-losing product lines;

narrowing the breadth of remaining

product

lines;

bringing customers to the company

headquarters to get their

opinions of new product

design

(which

surprisingly resulted in maintaining, rather than

changing, certain preferred features,

thus

holding

down redesign costs);

shifting production to outside

vendors, restructuring debt; amid

spinning

off most of its 250

stores. Eventually, these

changes led to closing five

plants and to

payroll

reductions of almost 35 percent.

The number of jobs lost would

have been much

greater,

however,

if Case had not implemented a variety of

downsizing methods.

Unfortunately,

organizations often choose

obvious solutions for downsizing, such as

layoffs,

because

they can be implemented quickly. This action

produces a climate of fear

and defensiveness

as

members focus on identifying

who will be separated from

the organization. Examining a broad

range

of options and considering the entire

organization rather than only certain

areas can help

allay

tears favoritism and

polities are the bases for

downsizing decisions. Moreover,

participation of

organization

members in such decisions

can have positive benefits.

It can create a sense of

urgency

for

identifying and implementing options to

downsizing other than layoffs.

Participation can

provide

members with a clearer understanding of

how downsizing will proceed

and can increase

the

likelihood that whatever

choices are made are

perceived as reasonable and

fair.

3.

Implement

the changes. This

stage involves implementing methods for

reducing the size oh

time

organization. Several practices

characterize successful implementation. First,

downsizing is

best

controlled from the top

down. Many difficult

decisions are required, and a broad

perspective

helps

to overcome people's natural instincts to

protect their enterprise or

function. Second,

identify

arid target specific areas of

inefficiency and high cost.

The morale of the organization

can

be

hurt if areas commonly known to be

redundant are left untouched. Third,

link specific actions

to

the organization's strategy. Organization members

need to be reminded consistently

that

restructuring

activities are part of a plan to improve

the organization's performance.

Finally,

communicate

frequently using a variety of media. This

keeps people informed, lowers

their anxiety

over

the process, and makes it

easier for them to focus on

their work.

Table

17

Three

Downsizing Tactics

Downsizing

Tactic

Characteristics

Examples

Workforce

reduction

Aimed

at headcount reduction

Attrition

Short-term

implementation

Transfer

and outplacement

Fosters

a transition

Retirement

incentives

Buyout

packages

Layoffs

Organization

redesign

Aimed

at organization change

Eliminates

functions

Moderate-term

implementation

Merge

units

Fosters

transition and potentially

Eliminate layers

transformation

Eliminate

products

Redesign

tasks

Systemic

redesign

Aimed

at culture change

Change

responsibility

Long-term

implementation

Involve

all constituents

Fosters

transformation

Foster

continuous improvement

and

innovation

Simplification

Downsizing

a way of life

4.

Address the needs of

survivors and those who

leave. Most

downsizing eventually involves

reduction

in

the size of the workforce, and it is

important to support not only

employees who remain with

the

organization

but also those who

leave. When layoffs occur,

employees are generally

asked to take on

additional

responsibilities and to lean new

jobs, often with little or

no increase in compensation. This

added

workload

can he stressful, arid when combined

with anxiety over past layoffs

and possible future ones,

it

can

lead to what researchers have

labeled time "survivor syndrome." This

syndrome involves a narrow

set

of

self-absorbed and risk-averse

behaviors that can threaten the

organization's survival. Rather

than

working

to ensure the organization's success, survivors

often are preoccupied with

whether additional

layoffs

will occur, with guilt

over receiving pay and

benefits while co workers are struggling

with

termination,

and with the uncertainty of career

advancement.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Organizations

can address these survivor

concerns with communication processes

that increase the amount

and

frequency of information provided.

Communication should shift from explanations about

who left or

why

to clarification of where the Company is

going, including its visions,

strategies, and goals. The

linkage

between

employees' performance and

strategic success is emphasized so

that remaining members feel they

are

valued. Organizations also can support

survivors through training and

development activities that

prepare

them for the new work they

are being asked to perform.

Senior management can

promote greater

involvement

in decision making, thus

reinforcing the message that people

are important to the

future

success

and growth of the organization.

Given

the negative consequences typically

associated with job loss,

organizations have developed an

array

of

methods to help employees

who have been laid

off. These include outplacement

counseling, personal

and

family counseling, severance

packages, office support for

job searches, relocation services,

and job

retraining.

Each service is intended to assist

employees in their transition to another

work situation.

1.

Follow

through with growth plans. This

final stage of downsizing involves

implementing an

Organization

renewal and growth process.

Failure to move quickly to implement growth

plans is a key

determinate

of ineffective downsizing For example, a

study of 1,020 human

resource directors reported

that

only 44 percent of the companies

that had downsized in the previous

live years shared details of

their

growth

plans with employees; only

34 percent told employees

how they would lit into the

company's new

strategy.

Organizations must ensure that

employees understand the renewal

strategy and their new

roles in

it.

Employees need credible

expectations that, although the organization

has been through a tough

period,

their

renewed efforts can move it

forward.

Results

of Downsizing:

The

empirical research on downsizing is mostly negative. A

review conducted by the National

Research

Council

concluded, "From the research produced

thus tar, downsizing as a strategy

for improvement has

proven

to be, by and large, a

failure." A number of studies base

documented the negative productivity

and

employee

consequences. One survey of 1,005

companies that used downsizing to

reduce costs reported

that

fewer than half of the firms

actually met cost targets.

Moreover, only 22 percent of the

companies

achieved

expected productivity gains,

and consequently about 80 percent of the

firms needed to rehire

some

of the same people that they had

previously terminated. Fewer than 33

percent of the companies

surveyed

reported that profits increased as

much as expected, and only

21 percent achieved

satisfactory

improvements

in shareholder return on investment.

Another survey of 1,142

downsized firms found

that

only

about a third achieved

productivity goals.39 In addition, the

research points to a number of

problems

at

the individual level, including increased

stress and illness, loss of

sell-esteem, reduced trust and

loyalty,

and

marriage and family

disruptions.

Research

on the effects of downsizing on financial performance

also shows negative results.

One study

examined

an array of financial performance

measures, such as return on

sales, assets, and equity,

in 210

companies

that announced layoffs. It found

that increases in financial performance

in the first year

following

the layoff announcements were

not followed by performance improvements

in the next year. In

no

case did a firm's financial

performance after a layoff announcement

match its maximum levels

of

performance

in the year before the announcement.

These results suggest that

layoffs may result in

initial

improvements

iii financial performance,

hut such gains are temporary

and not sustained at even

pre-layoff

levels.

In a sin3ilar study of sixteen firms

that wrote off more

than 10 percent of their net

worth in a live-

year

period, stock prices, which

averaged 16 percent below the

market average before the

layoff

announcements,

increased on the day that the

restructuring was announced but

then began a steady

decline.

Two

years after the layoff announcements, ten

of the sixteen stocks were

trading below the market by

17

percent

to 48 percent, and twelve of the sixteen

were below comparable firms in their

industries by 5 to 45

percent.

These

research findings paint a rather

bleak picture of the success of downsizing.

The results must be

interpreted

cautiously, however, for three

reasons.

First, many

of the survey-oriented studies received

responses from human

resources specialists who

might

have

been naturally inclined to view

downsizing in a negative light.

Second, the

studies of financial performance may

have included a biased sample of firms.

If the companies

selected

for analysis had been

poorly managed, then downsizing

alone would have been

unlikely to improve

financial

performance. There is some empirical

support for this view

because low-performing firms

are

more

likely to engage in downsizing than are

high-performing firms.

Third,

disappointing results may be a

function of the way downsizing was

implemented. A number of

organizations

have posted solid financial returns

following downsizing, such as Florida

Power and Light,

General

Electric, Motorola, Texas instruments,

Boeing, Chrysler, and Hewlett-Packard. A

study of thirty

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

downsized

firms in the automobile industry showed

that those companies that

implemented effectively the

process

described above scored significantly

higher on several performance measures

than did firms that

had

no downsizing strategy or that implemented the

steps poorly. Several

studies have suggested that

where

downsizing

programs adopt appropriate CD

interventions or apply strategies similar

to the process outlined

above,

they generate more positive

individual and organizational results.

Thus, the success of downsizing

efforts

may depend as much on how

effectively the intervention is applied as on the

size of the layoffs or

the

amount of delayering.

Reengineering:

The

final restructuring intervention is

reengineering--the fundamental rethinking

and radical redesign

of

business

processes to achieve dramatic

improvements in performance Reengineering

transforms how

organizations

traditionally produce and

deliver goods and services.

Beginning with the Industrial

Revolution,

organizations have increasingly

fragmented work into

specialized units, each focusing on

a

limited

pan of the overall production

process. Although this division of

labor has enabled

organizations to

mass-produce

standardized products and services

efficiently, it can be overly

complicated, difficult to

manage,

and slow to respond to the

rapid and unpredictable changes

experienced by many

organizations

today.

Reengineering addresses these

problems by breaking down specialized

work units into more

integrated,

cross-functional work processes.

This streamlines work

processes and makes them

faster and

more

flexible; consequently they are

more responsive to changes in

competitive conditions, customer

demands,

product life cycles, and

technologies.

As

might be expected, reengineering

requires an almost revolutionary

change in how organizations

design

their

structures and their work.

It addresses fundamental issues about

why organizations do what they

do,

and

why do they do it in a particular way.

Reengineering identifies and questions

the often unexamined

assumptions

underlying how organizations

perform work. This effort

typically results in radical

changes in

thinking

and work methods a shift

front specialized job,

tasks, and structures to integrated

processes that

deliver

value to customers. Such

revolutionary change differs

considerably from incremental

approaches to

performance

improvement, such as continuous improvement

and total quality

management, which

emphasize

Incremental changes in existing work

processes. Because reengineering

radically alters the

status

quo,

it seeks to produce dramatic

Increases In organization

performance.

In

radically changing business

processes, reengineering frequently

takes advantage of new

Information

technology.

Modern information technologies,

such as teleconferencing, expert systems,

shared databases,

and

wireless communication, can enable

organizations to reengineer. They can

help organizations to

break

out

of traditional ways of thinking

about work and embrace

entirely new ways of

producing and

delivering

products.

At IBM Credit, for example, an integrated

information system with expert

systems technology

enables

one employee to handle all

stages of the credit-delivery process.

This eliminates the handoffs,

delays,

and errors that derived from

the traditional work design, in

which different employees

performed

sequential

tasks.

Whereas

new information technology can

enable organizations to reengineer

themselves, existing

technology

can thwart such efforts.4'

Many reengineering projects

fail because existing information

systems

do

not provide the data needed

to operate integrated business processes.

The systems do not

allow

Interdependent

departments to interface with each

other they often require new

Information to be entered

by

hand into separate computer systems

before people in different work areas

can access it. Given

the

inherent

difficulty in trying to support

process-based work with

specialized information

systems,

organizations

have sought to develop information

technologies that are more

suited to reengineered

work.

The

most popular software

system, SAR was developed by a German

company of the same name.

With

SAI

firms can standardize their

information systems because the

software processes data on a

range of

tasks

and links ft all together,

thus integrating the information flow

among different pans of the

business.

Because

they believe that SAP may be

the missing technological link to

reengineering, many of the

largest

consulting

firms that provide

reengineering services, such as

Anderson Consulting, Deloitte Touché,

and

Price

water house Coopen, have developed

their own SAP

consultants.

Reengineering

also is associated with

interventions having to do with downsizing, the

shift from functional

to

process-based structures, and

work design. Although these

Interventions have different

conceptual and

applied

backgrounds, they overlap considerably in

practice. Reengineering can

result in production

and

delivery

processes that require fewer people

and fewer layers of

management. Conversely, down

sizing may

require

subsequent reengineering interventions.

When downsizing occurs without

fundamental changes in

how

work is performed, the same tasks simply

are being performed with a

smaller number of people. Thus,

expected

cost savings may not be

realized because lower

productivity offsets lower

salaries and fewer

benefits.

Reengineering

also can be linked to

transformation of organization structures

and work design. Its

focus on

work

processes helps to break

down the vertical orientation of

functional and

self-contained--unit

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

organizations.

The endeavor identifies and

assesses core business

processes and redesigns work

to account

for

key task interdependencies

running through them. That

typically results in new

jobs or teams that

emphasize

multifunctional tasks, results-oriented

feedback, and employee

empowerment characteristics

associated

with motivational and

socio-technical approaches to work

design. Regrettably, reengineering

has

failed

to apply these approaches attention to

individual differences in people's

reactions to work to its

own

work-design

prescriptions. It advocates enriched

work and teams, without

consideration for the wealth of

research

that shows that not

all people are motivated to

perform such work.

Application

Stages:

Reengineering

is a relatively new intervention and is

still developing applied methods.

Early applications

emphasized

identifying which business

processes to reengineer and technically

assessing the work

flow.

More

recent efforts have extended

reengineering practice to address

issues of managing change,

such as

how

to deal with resistance to

change and how to manage the

transition to new work

processes. The

following

application steps are included in

most reengineering efforts,

although the order may

change

slightly

from one situation to

another.

1.

Prepare

the organization. Reengineering

begins with clarification

and assessment of the

organization's

context,

including

its

competitive

environment,

strategy,

and objectives. This effort

establishes the need for

reengineering and the

strategic

direction

that the process should follow.

Changes in an organization' competitive

environment can

signal

a need for radical change in

how it does business. As preparation

for reengineering at

GTE

Telephone

Operations, for example, executives

determined that although deregulation had

begun

with

coin-operated telephones and

long-distance service, it soon

would spread to the

local

network.

They concluded that this

would present an enormous

competitive challenge and

that the

old

way of doing business, reinforced by

years of regulatory protection, would

seriously saddle the

organization

with high costs.

2.

Specify

organization strategy and objectives. The

business strategy determines the

focus of

reengineering

and guides decisions about the

business processes that are

essential for

strategic

success.

In the absence of such information, the

organization may reengineer extraneous

processes

or

ones that could be outsourced.

GTE executives recognized

that the keys to the firm's

success in

a

more competitive environment

were low costs and

customer satisfaction. Consequently, they

set

dramatic

goals of doubling revenues

while halving costs and

reducing product development time

by

75 percent. Defining these

objectives gave the reengineering

effort a clear focus. A

final task in

this

preparation step is to communicate

clearly throughout the organization why

reengineering is

necessary

and the direction it will

lake. GTE's communications program

lasted a year and a

half,

and

helped ensure that members understood the

reasons underlying the program and

the

magnitude

of the changes to be made. Senior

executives were careful to

communicate, both

verbally

and behaviorally, that they

were fully committed to the change

effort. Demonstration of

such

unwavering support seems necessary if Organization

members are to challenge

their

traditional

thinking about how business

should he conducted.

3.

Fundamentally

rethink the way work gets

done. This

step lies at the heart of

reengineering and

involves

these activities: identifying

and analyzing core business

processes, defining their

key

performance

objectives, and designing

new processes. These tasks

are the real work of

reengineering

and typically are performed

by a cross-functional team who is given

considerable

time

and resources to accomplish

them.

a.

Identify

and analyze core business

processes. Core

processes are considered

essential for

strategic

success. They include activities that transform

inputs into valued outputs.

Core processes

typically

are assessed through development of a

process map that lists the

different activities

required

to deliver an organization's products or services.

GTE determined that its core

processes

could

be characterized as "choose, use,

and pay." Customers first

choose a telephone carrier, then

use

its services, and pay

for them. GTE developed a

process map for these

core processes that

included

the work flow for getting

customers to choose, use,

and pay for the firm's

service.

Analysis

of core business processes

can include assigning costs to

each of the major phases of the

work

flow

to help identify costs that

may be hidden in the activities of the

production process. Traditional

cost-

accounting

systems do not store data in

process terms; they identify

costs according to categories

of

expense,

such as salaries, fixed

costs, and supplies. This

method of cost accounting can he

misleading and

can

result in erroneous conclusion

about how best to reduce

costs.

For

example, the material control department

at a Dana Corporation plant in

Plymouth, Minnesota,

changed

from a traditional to a process-based

accounting system. The

traditional accounting

system

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

showed

that salaries and fringe

benefits accounted for 82 percent of

total costs--an assessment

that

suggested

workforce downsizing was the most

effective way to lower costs.

The process-based

accounting

system

revealed a different picture, however: it

showed that 44 percent of the

department's costs

involved

expediting,

resolving, and reissuing orders

from suppliers and

customers. In other words,

almost half of

their

costs were associated with

reworking deficient

orders.

Business

processes also can be

assessed in terms of value-added

activities the amount of value

contributed

to

a product or service by a particular step

in the process. For example, as

part of its invoice

collection

process,

Corky's Pest Control, a small

service business dependent on a

steady stream of cash

payments,

provides

its customers with a

sell-addressed, stamped envelope.

Although this adds an additional

cost to

each

account, it more than pays

for itself in customer

loyalty arid retention, and

reduced accounts

receivables

arid late payments handling. Conversely,

Organizations often engage in

process activities that

have

little or no added value.

For instance, in a Denver hospital an

employee on each workshift

checked a

pump

that circulated oxygen.

Eight years earlier, the pump

had failed and caused a

death. Since that time,

a

new

pump had been installed with

fault-protection equipment and control

sensors that no longer required

the

physical inspection. Yet because of

habit, the checking process

remained in place and drained

resources

that

could be used more productively in

other areas.

b.

Define performance objectives. Challenging

performance goals are set in

this step. The

highest

possible

level of performance for any particular

process is identified, and

dramatic goals are set

for speed,

quality,

cost, or other Inca- sores

of performance. These standards

can derive from customer

requirements

or

from benchmarks of the best

practices of industry leaders. For

example, at Andersen Windows, the

demand

for unique window shapes

pushed the number of different products

from 28,000 to more

than

86,000

in 1991. The pressure on the

shop floor for a "batch of

one" resulted in 20 percent of

all shipments

containing

at least one order

discrepancy. As part of its

reengineering effort, Andersen set

targets for ease

of

ordering, manufacturing, and delivery.

Each retailer and distributor

was sold an interactive,

computerized

version of its catalogue that allowed

customers to design their

own windows. The resulting

design

is then given a unique "license plate

number" and the specifications

are sent directly to the

factory.

By

1995, new sales had

tripled at some retail locations, the

number of products had increased to

188,000,

and

fewer than one in two

hundred shipments had a

discrepancy.

c.

Design new processes. The

last task in this third step

of reengineering is to redesign current

business

processes

to achieve breakthrough goals. It

often starts with a clean

sheet of paper and addresses

the

question

"If we were starting this company today,

what processes would we need to

create a sustainable

competitive

advantage?" These essential

processes are then designed

according to the following

guidelines:

·

Begin

and end the process with the

needs and wants of the

customer.

·

Simplify

the current process by combining and

eliminating steps.

·

Use

the "best of what is" in the current

process.

·

Attend

to both technical and social

aspects of the process.

·

Do

not be constrained by past

practice.

·

Identify

the critical information required at each

step in the process.

·

Perform

activities in their most natural

order.

·

Assume

the work gets done right the

first time.

·

Listen to

people who do the work.

An

important activity that

appears in many successful

reengineering efforts is implementing

"early wins" or

"quick

hits." Analysis of existing processes

often reveals obvious

redundancies and inefficiencies for

which

appropriate

changes may be authorized immediately.

These early successes can

help generate and

sustain

momentum

in the reengineering effort.

4.

Restructure

the organization around the

new business processes. This

last step in

reengineering

involves changing the organization's

structure to support the new

business

processes.

This endeavor typically

results in the kinds of process-based

structures that were

described

earlier in this chapter. An important

element of this restructuring is implementing

new

information

and measurement systems that

reinforce a shift from measuring

behaviors, such as

absenteeism

and grievances, to assessing

outcomes, such as productivity,

customer satisfaction,

and

cost

savings. Moreover, information technology

IS one of the key drivers of

reengineering because

it

can drastically reduce the

cost and time associated

with integrating and coordinating

business

processes.

Table of Contents:

- The Challenge for Organizations:The Growth and Relevance of OD

- OD: A Unique Change Strategy:OD consultants utilize a behavioral science base

- What an “ideal” effective, healthy organization would look like?:

- The Evolution of OD:Laboratory Training, Likert Scale, Scoring and analysis,

- The Evolution of OD:Participative Management, Quality of Work Life, Strategic Change

- The Organization Culture:Adjustment to Cultural Norms, Psychological Contracts

- The Nature of Planned Change:Lewin’s Change Model, Case Example: British Airways

- Action Research Model:Termination of the OD Effort, Phases not Steps

- General Model of Planned Change:Entering and Contracting, Magnitude of Change

- The Organization Development Practitioner:External and Internal Practitioners

- Creating a Climate for Change:The Stabilizer Style, The Analyzer Style

- OD Practitioner Skills and Activities:Consultant’s Abilities, Marginality

- Professional Values:Professional Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, Technical Ineptness

- Entering and Contracting:Clarifying the Organizational Issue, Selecting an OD Practitioner

- Diagnosing Organizations:The Process, The Performance Gap, The Interview Data

- Organization as Open Systems:Equifinality, Diagnosing Organizational Systems

- Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Methods for Collecting Data, Observations

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Sampling, The Analysis of Data

- Designing Interventions:Readiness for Change, Techno-structural Interventions

- Leading and Managing Change:Motivating Change, The Life Cycle of Resistance to Change

- Leading and managing change:Describing the Core Ideology, Commitment Planning

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Measurement

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Research Design

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Group Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Leadership and Authority, Group Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Third-Party Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Building, Team Building Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Management Styles

- Organization Process Approaches:Application Stages, Microcosm Groups

- Restructuring Organizations:Structural Design, Process-Based Structures

- Restructuring Organizations:Downsizing, Application Stages, Reengineering

- Employee Involvement:Parallel Structures, Multiple-level committees

- Employee Involvement:Quality Circles, Total Quality Management

- Work Design:The Engineering Approach, Individual Differences, Vertical Loading

- Performance Management:Goal Setting, Management by Objectives, Criticism of MBO

- Developing and Assisting Members:Career Stages, Career Planning, Job Pathing

- Developing and Assisting Members:Culture and Values, Employee Assistance Programs

- Organization and Environment Relationships:Environmental Dimensions, Administrative Responses

- Organization Transformation:Sharing the Vision, Three kinds of Interventions

- The Behavioral Approach:The Deep Assumptions Approach

- Seven Practices of Successful Organizations:Training, Sharing Information