|

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

30

Interpersonal

and Group Process

Approaches

3.

Third-Party Interventions

Third-party

intervention focuses on conflicts arising

between two or more people

within the same

organization.

Conflict is inherent in groups

and organizations and can

arise from a variety of

sources,

include

differences in personality, task

orientation, and perceptions

among group members, as well

as

competition

for scarce resources. To

emphasize that conflict is

neither good nor bad

per se is important.

Conflict

can enhance motivation and

innovation and lead to

greater understanding of ideas and

views. On

the

other hand, it can prevent

people from working together constructively,

destroying necessary task

interactions

among group members.

Consequently, third-party intervention is

used primarily in situations

in

which

conflict significantly disrupts necessary

task interactions and work relationships

among members.

Third-party

intervention varies considerably

depending on the kind of issues

underlying the conflict.

Conflict

can arise over substantive

issues, such as work

methods, pay rates, and

conditions of employment;

or

it can emerge from interpersonal

issues, such as personalities

and misperceptions. When applied

to

substantive

issues, conflict resolution

interventions often involve resolving

labor-management disputes

through

arbitration and mediation. The

methods used in such

substantive interventions require

considerable

training and expertise in

law and labor relations and

generally are not considered

part of OD

practice.

For example, when union and

management representatives cannot resolve

a joint problem, they

can

call upon the Federal

Mediation and Conciliation

Service to help them resolve the

conflict. In addition,

"alternative

dispute resolution" (ADR)

practices increasingly are

offered in lieu of more

expensive and

time-consuming

court trials. Conflicts also

may arise at the boundaries of the

organization, such as between

suppliers

and the company or between a

company and a public policy

agency.

When

conflict involves interpersonal issues,

however, OD has developed approaches that

help control and

resolve

it. These third-party

interventions help the parties interact

with each other directly,

facilitating their

diagnosis

of the conflict and how to

resolve it. That ability to

facilitate conflict resolution is a basic

skill in

OD

and applies to all of the

process interventions. Consultants,

for example, frequently help

organization

members

resolve interpersonal conflicts that

invariably arise during

process consultation and team

building.

Third-party

consultation interventions cannot resolve

all interpersonal conflicts in organizations,

nor

should

they. Many times, interpersonal conflicts

are not severe or disruptive

enough to warrant attention.

At

other times, they simply may

burn themselves out. Evidence

also suggests that other

methods may be

more

appropriate under certain conditions. For

example, managers tend to

control the process

and

outcomes

of conflict resolution actively when they

are under heavy time pressures, when the

disputants are

not

expected to work together in the future,

and when the resolution of the

dispute has a broad impact

on

the

organization. Under those conditions, the

third party may resolve the

conflict unilaterally with

little

input

from the conflicting

parties.

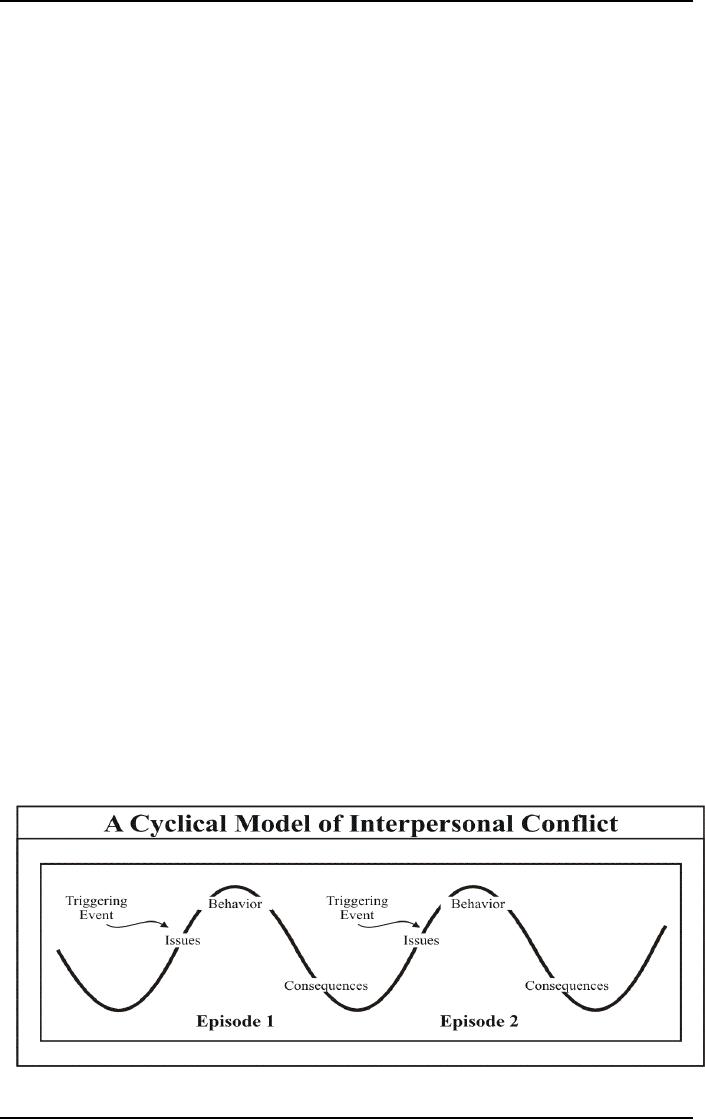

An

Episodic Model of

Conflict:

Interpersonal

conflict often occurs in iterative,

cyclical stages known as "episodes." An

episodic model is

shown

in Figure 39. At times, issues

underlying a conflict are latent

and do not present any

manifest

problems

for the parties. Then

something triggers the conflict

and brings it into the open.

For example, a

violent

disagreement or frank confrontation

can unleash conflictual

behavior. Because of the

negative

consequences

of that behavior, the unresolved

disagreement usually becomes latent

again. And again,

something

triggers the conflict, making it overt,

and so the cycle continues

with the next conflict

episode.

Figure

39: A cyclical Model of

Interpersonal Conflict

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Conflict

has both costs and benefits

to the antagonists and to those in

contact with them.

Unresolved

conflict

can proliferate and expand.

An interpersonal conflict may be

concealed under a cause or issue

that

serves

to make the conflict appear

more legitimate. Frequently, the overt

conflict is only a symptom of

a

deeper

problem.

The

episode model identifies four

strategies for conflict resolution.

The first three attempts to

control the

conflict

and only the last approach

try to change the basic

issues underlying it. The

first strategy is to

prevent

the ignition of conflict by arriving at a

clear understanding of the triggering

factors and thereafter

avoiding

or blunting them when the symptoms occur.

For example, if conflict

between the research

and

production

managers is always triggered by new

product introductions, then

senior management can

warn

them

that conflict will not be

tolerated during the introduction of the

latest new product. However

this

approach

may not always be functional

and merely may drive the

conflict underground until it

explodes. As

a

control strategy, however, this method

may help to achieve a temporary

cooling-off period.

The

second control strategy is to

set limits on the form of the

conflict. Conflict can be

constrained by

informal

gatherings before a formal meeting or by

exploration of other options. It

also can be limited

by

setting

rules and procedures

specifying the conditions under which the

parties can interact. For

example, a

rule

can be instituted that union

officials can attempt to resolve

grievances with management

only at weekly

grievance

meetings.

The

third control strategy is to

help the parties cope

differently with the consequences of the

conflict. The

third-party

consultant may work with the people

involved to devise coping techniques,

such as reducing

their

dependence on the relationship, ventilating

their feelings to friends, and

developing additional

sources

of

emotional support. These methods

can reduce the costs of the

conflict without resolving the

underlying

issues.

The

fourth method is an attempt to eliminate or to resolve

the basic issues causing the

conflict. As Walton

points

out, "There is little to he

said about this objective because it is the

most obvious and

straightforward,

although it is often the most

difficult to achieve."

Facilitating

the Conflict Resolution

Process:

Walton

has identified a number of factors

and tactical choices that

can facilitate the use of the

episode

model

in resolving the underlying causes of

conflict. The following ingredients

can help third-party

consultants

achieve productive dialogue

between the disputants so that they

examine their differences

and

change

their perceptions and

behaviors: mutual motivation to resolve

the conflict; equality of power

between

the parties; coordinated attempts to

confront the conflict; relevant phasing

of the stages of

identifying

differences and of searching

for integrative solutions; open and clear

forms of communication;

and

productive levels of tension and

stress.

Among

the tactical choices identified by

Walton do those having to do with

diagnosis, the context of the

third-party

intervention, and the role of the

consultant. One of the tactics in

third-party intervention is the

gathering

of data, usually through

preliminary interviewing. Group-process

observations can also be

used.

Data

gathering provides some understanding of the nature

and the type of conflict, the personality

and

conflict

styles of the individuals involved, the

issues and attendant pressures,

and the participants' readiness

to

work together to resolve the

conflict.

The

context in which the intervention

occurs is also important. Consideration

of the neutrality of the

meeting

area, the formality of the setting, the

appropriateness of the time for the

meeting (that is, a

meeting

should

not be started until a time

has been agreed on to

conclude or adjourn), and the careful

selection of

those

who should attend the meeting are

all elements of this context.

In

addition, the third-party consultant must

decide on an appropriate role to assume

in resolving conflict.

The

specific tactic chosen will

depend on the diagnosis of the situation.

For example, facilitating

dialogue

of

interpersonal issues might include

initiating the agenda for the

meeting, acting as a referee

during the

meeting,

reflecting and restating the issues

and the differing perceptions of the

individuals involved,

giving

feedback

and receiving comments on the

feedback, helping the individuals

diagnose the issues in

the

conflict,

providing suggestions or recommendations,

and helping the parties do a better

job of diagnosing

the

underlying problem.

The

third-party consultant must develop

considerable skill at diagnosis,

intervention, and follow-up.

The

third-party

intervener must be highly sensitive to

his or her own feelings

and to those of others. He or

she

also

must recognize that some

tension and conflict are

inevitable and that although

there can be an

optimum

amount and degree of conflict,

too much conflict can be

dysfunctional for both the people

involved

and the larger organization. The

third-party consultant must be sensitive

to the situation and

able

to

use a number of different intervention

strategies and tactics when

intervention appears to be

useful.

Finally,

she or he must have

professional expertise in third-party

intervention and must be

seen by the

parties

as neutral or unbiased regarding the

issues and outcomes of the

conflict resolution.

Application

6 describes an attempt to address

conflict in an information technology

unit. How does this

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

description

fit with the process

described above? What would

you have done

differently?

Application

6: Conflict Management at Balt Healthcare

Corporation

Pete

and Dan were managers in an

IT department that was part of the

information services group at

Bait

Healthcare

Corporation, a large organization that

provided health-care products to a global

market. Pete

was

the general manager of the IT department

and had been working in the

unit for most of his 16

years

with

Bait. The IT department had global responsibility

for developing and maintaining the

organization's

intranets,

Websites, and internal networks.

Pete ran his department with

a traditional and

formal

management

style where communication traveled vertically

through the hierarchy.

Dan

recently had been assigned

to Pete's department to operate a small

experimental group charged

with

developing

e-commerce solutions for the organization

and the industry. This was

state-of-the-art

development

work with enormous future

implications for the organization as it explored the

possibility of

sales,

business-to-business and other supply

chain opportunities on the Internet.

Dan, in contrast to

Pete,

had

a management style that

stressed the value of open communication

channels to promote teamwork

and

collaboration.

The

biggest challenge in Dan's

work was managing the

transition from design into

production. Senior

management

at Bait believed that by assigning

Dan's team to Pete's organization, the

resources required to

manage

this transition would be more readily

available to Dan's group. In fact, it

was generally agreed

that

Pete's

strengths complimented Dan's weaknesses.

Whereas Dan was a better

designer, Pete had

operational

expertise

that would help in bringing

Dan's ideas online.

Unfortunately,

the trouble started almost as

soon as the assignment was

announced. Although in front

of

their

bosses Pete had agreed to

work with Dan to make the

project a success, his

support was lukewarm at

best.

Dan and Pete had a

history of conflict in the organization.

Neither one respected the other's

style, and

prior

conflicts had been swept under the

carpet, creating a considerable amount of

pent-up animosity.

Operationally,

when Dan's group needed

resources to bring an idea

online, Pete announced that

all of his

people

were busy and that he

couldn't assign anyone to help.

Similarly, anytime Dan needed

access to a

piece

of hardware within the IT unit.

Pete made it complicated to

get that access. Dan

became increasingly

frustrated

by Pete's lack of cooperation and he

was quite open about his

feelings of being sabotaged.

His

complaints

reached the highest levels of

management as well as other

members of the information

services

staff.

After

several frustrating attempts to

speak with Pete about the

situation, Dan consulted Marilyn, the

vice

president

for information services.

Marilyn, like others in the organization,

was aware of the conflict.

She

requested

assistance from the human

resources manager and an organization

development specialist. The

OD

specialist met with Pete

and Dan separately to

understand the history of the conflict

and each

individuals

contribution to it. Although

different styles were partly

to blame, the differences in the

two

work

processes were also

contributing to the problem. Pete's organization

was primarily routine

development

and maintenance tasks that

allowed for considerable preplanning

and scheduling of

resources.

Dan's

project, however, was highly creative

and unpredictable. There was little

opportunity to give Pete

advance

notice regarding the experimental team's

needs for equipment and

other resources.

The

OD specialist recommended several

strategies to Marilyn, including a direct

confrontation, the

purchase

of additional hardware and

software, and mandating the antagonists'

cooperation. Marilyn

responded

that there was no available

budget for purchasing new equipment

and admitted that she did

not

have

any confidence in her ability to

facilitate the needed communication and

leadership for her staff.

She

asked

the OD specialist to facilitate a more direct

process. Agreements were

made in writing about how

the

process

would work, including

Marilyn meeting with Dan

and Pete to discuss the

problem between them

and

how it was affecting the organization.

But Marilyn did not

follow through on the agreement.

She never

met

with Pete and Dan at the

same time and, as a result, the

messages she sent to each

were inconsistent.

In

fact, during their separate

conversations, it appeared that

Marilyn began supporting

Pete and began

criticizing

Dan. Dan began to withdraw,

productivity in both groups

suffered, and he became more

hostile,

stubborn,

and bitter.

In

the end, Dan felt sabotaged

not only by Pete but by

Marilyn as well. He took a leave of

absence based

on

Marilyn's advice. His

project was left without a

leader and he ended up leaving the

organization. Pete

stayed

on, but staff at all levels

of the organization were upset that

his behavior had not

been questioned.

Similarly,

the organization lost a lot of respect

for Marilyn's ability to

address conflict. Losses

in

productivity

and morale among staff in

many areas in the organization resulted

from the conflict

between

two

employees.

Table of Contents:

- The Challenge for Organizations:The Growth and Relevance of OD

- OD: A Unique Change Strategy:OD consultants utilize a behavioral science base

- What an “ideal” effective, healthy organization would look like?:

- The Evolution of OD:Laboratory Training, Likert Scale, Scoring and analysis,

- The Evolution of OD:Participative Management, Quality of Work Life, Strategic Change

- The Organization Culture:Adjustment to Cultural Norms, Psychological Contracts

- The Nature of Planned Change:Lewin’s Change Model, Case Example: British Airways

- Action Research Model:Termination of the OD Effort, Phases not Steps

- General Model of Planned Change:Entering and Contracting, Magnitude of Change

- The Organization Development Practitioner:External and Internal Practitioners

- Creating a Climate for Change:The Stabilizer Style, The Analyzer Style

- OD Practitioner Skills and Activities:Consultant’s Abilities, Marginality

- Professional Values:Professional Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, Technical Ineptness

- Entering and Contracting:Clarifying the Organizational Issue, Selecting an OD Practitioner

- Diagnosing Organizations:The Process, The Performance Gap, The Interview Data

- Organization as Open Systems:Equifinality, Diagnosing Organizational Systems

- Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Methods for Collecting Data, Observations

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Sampling, The Analysis of Data

- Designing Interventions:Readiness for Change, Techno-structural Interventions

- Leading and Managing Change:Motivating Change, The Life Cycle of Resistance to Change

- Leading and managing change:Describing the Core Ideology, Commitment Planning

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Measurement

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Research Design

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Group Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Leadership and Authority, Group Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Third-Party Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Building, Team Building Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Management Styles

- Organization Process Approaches:Application Stages, Microcosm Groups

- Restructuring Organizations:Structural Design, Process-Based Structures

- Restructuring Organizations:Downsizing, Application Stages, Reengineering

- Employee Involvement:Parallel Structures, Multiple-level committees

- Employee Involvement:Quality Circles, Total Quality Management

- Work Design:The Engineering Approach, Individual Differences, Vertical Loading

- Performance Management:Goal Setting, Management by Objectives, Criticism of MBO

- Developing and Assisting Members:Career Stages, Career Planning, Job Pathing

- Developing and Assisting Members:Culture and Values, Employee Assistance Programs

- Organization and Environment Relationships:Environmental Dimensions, Administrative Responses

- Organization Transformation:Sharing the Vision, Three kinds of Interventions

- The Behavioral Approach:The Deep Assumptions Approach

- Seven Practices of Successful Organizations:Training, Sharing Information