|

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

28

Interpersonal

and Group Process

Approaches

Process

Interventions:

Process

interventions are in OD skill

used by OD practitioners, whether managers or OD

professionals, to

help

work groups become more

effective. The purpose of process

interventions is to help the work

group

become

more aware of the way it

operates and the way its

members work with one

another. The work

group

uses this knowledge to develop its own

problem-solving ability. Process

interventions, then, aim at

helping

the work group to become

more aware of its own

processes, including the way it

operates, and uses

this

knowledge to solve its own

problems.

The

manager practicing process intervention

observes individuals and

teams in action and helps them

learn

to

diagnose and solve their

own problems. The manger

refrains from telling them

how to solve their

problems

but instead asks questions,

focuses their attention on

how they are working together,

teaches or

provides

resources where necessary,

and listens. On of the major advantages

is that teams becomes

more

independent

to solve problems.

Now

we will discuss change

programs relating to interpersonal relations and

group dynamics. These

change

programs

are among the earliest ones

devised in OD and represent

attempts to improve people's

working

relationships

with one another. The

interventions are aimed at

helping group members assess

their

interactions

and devise more effective

ways of working together. These

interventions represent a basic

skill

requirement

for an OD practitioner.

Interpersonal

relationships and group dynamics,

involve four types of

interventions:

1.

T-group.

2.

Process consultation.

3.

Third-party intervention.

4.

Team building.

1.

T-Groups

As

discussed earlier, sensitivity training, or the

T-group, is an early forerunner of modern

OD

interventions.

Its direct use in OD has

lessened considerably. The

National Training Laboratories

(NTL)

and

UCLA are among the few remaining

organizations that offer

T-groups on a regular basis.

OD

practitioners

often attend T-groups to improve

their own functioning. For

example, T-groups can help

OD

practitioners

become more aware of how

others perceive them and

thus increase their

effectiveness with

client

systems. In addition, OD practitioners

often recommend that organization

members attend a T-

group

to learn how their behaviors

affect others and to develop more

effective ways of relating to

people.

What

Are the Goals?

T-groups

traditionally are designed to

provide members with experiential

learning about group dynamics,

leadership,

and interpersonal relations. The

basic T-group consists of ten to

fifteen strangers who

meet

with

a professional trainer to explore the social

dynamics that emerge from

their interactions. Modifications

of

this basic design have

generally moved in two directions. The

first path has used

T-group methods to

help

individuals gain deeper

personal understanding and development.

This intrapersonal focus typically

is

called

an encounter group or a personal-growth group. It

generally is considered outside the

boundaries of

OD

and should be conducted only by

professionally trained clinicians. The

second direction uses

T-group

techniques

to explore group dynamics and

member relationships within an intact

work group. Considerable

training

in T-group methods and group

dynamics should he acquired before trying

these interventions.

This

group

focus has led to the OD intervention

called team building, which

is discussed later.

Extensive

review of the literature reveals that

there are six overall

objectives common to most

T-groups,

although

not every practitioner need

accomplish every objective in every

T-group. These objectives

are:

1.

Increased

understanding, insight, and

self-awareness about one's

own behavior and its

impact on

others,

including the ways in which

others interpret one's

behavior.

2.

Increased

understanding and sensitivity about the

behavior of others, including

better

interpretation

of both verbal and nonverbal

clues, which increases

awareness and understanding

of

what

other people are thinking

and feeling.

3.

Better

understanding and awareness of group

and inter-group processes,

both those that

facilitate

and

those that inhibit group

functioning.

4.

Increased

diagnostic skills in interpersonal and

inter-group situations. Accomplishing the

first three

objectives

provides the basic tools for

accomplishing the fourth

objective.

5.

Increased

ability to transform learning

into action so that

real-life interventions

will

be successful in increasing member

satisfaction, output, or

effectiveness.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

6.

Improvement

in individuals' ability to analyze

their own interpersonal behavior as

well as to learn

how

to help themselves and

others with whom they come

in contact, achieve more

satisfying,

rewarding,

and effective interpersonal

relationships.

These

goals seem to meet many

T-group applications, although

any one training program may

emphasize

one

goal more than the others.

One trainer may emphasize understanding

group process as applied to

organizations;

another may focus on group

process as a way of developing

individuals' understanding of

themselves

and others; and a third

trainer may concentrate

primarily on interpersonal and

intrapersonal

learning.

Application

Stages

Application

4 illustrates the activities occurring in a typical unstructured

strangers T-group, one of the

most

popular

approaches.

Application

4: Unstructured Strangers

T-group

A

typical T-group session for

strangers might consist of

five or six T-groups of ten to

fifteen members who

have

signed up for a Session

conducted by the National Training

Laboratories, UCLA's Ojai program,

a

university,

or a similar organization. The T-group

sessions may be combined with

cognitive learning, such

as

brief lectures on general

theory, designed exercises, or

management games.

Each

T-group comprises people who

have not previously known

one another. If several people

from the

same

organization attend, they are put into

different T-groups. At the beginning of the training

session, the

trainer

makes a brief and ambiguous

statement about either his or her

role or some ground rules

and lapses

into

silence. Because the trainer has

not taken a leadership role

or provided goals for the group, a

dilemma

of

leadership and agenda is

created. The group must

work out its own

methods to proceed further; it

must

fill

the void left by the lack of a

leader or of group

objectives.

As

the group fills the void, the

individuals' behaviors become the

"here-and-now" basic data

for the

learning

experiences. As the group struggles

with procedure, individual

members try out different

behaviors

and

roles, many of which are

unsuccessful. One T-group member

might make a number of direct,

forceful,

and

unsuccessful attempts to take

over the leadership role, trying

first one style, then

another. Finally, he or

she

conspicuously withdraws from the group,

falls silent, and appears to

be thinking about other

things.

Group

members might observe that

this person has two basic

styles of working with

others; when one

style

is

unsuccessful, he or she adopts the

other--withdrawal.

As

appropriate, the trainer will make an

"intervention," an observation or comment

about the group, its

behavior

or the activities that are

taking place. The type and

nature of the intervention will

vary, depending

on

the purpose of the laboratory and the

trainer's own style. Usually, the trainer

encourages individuals to

understand

what is going on in the group, their own

feelings and behaviors, and

the impact their behavior

has

on themselves and others.

The primary emphasis is on the here-and-now

experience, rather than on

anecdotes

or "back at the ranch"

experiences.

The

emphasis on openness and leveling in a

supportive and caring

environment enables the participants

to

gain

insight into their own

and others' feelings and

behaviors. A better understanding of group

dynamics

also

can make them more

productive individuals.

2.

Process Consultation:

Process

consultation (PC) is a general framework

for carrying out helping

relationships. It is oriented to

helping

managers, employees, and

groups assess and improve

processes, such as communication,

interpersonal

relations, decision making and

task performance. Schein

argues that effective consultants

and

managers

should be good helpers, aiding others in

getting things done and in achieving the

goals they have

set.

Thus, PC is more a philosophy

than a set of techniques

aimed at performing this helping

relationship.

The

philosophy ensures that

those who are receiving the

help own their problems,

gain the skills and

expertise

to diagnose them, and solve

them themselves. Thus, it is an approach

to helping people and

groups

help themselves.

Schein

defines process consultation as "the

creation of a relationship that permits the

client to perceive,

understand,

and act on the process

events that occur in

(her/his) internal and external

environment in

order

to improve the situation as defined by the

client." The process consultant

does not offer expert

help

in

the form of solutions to problems, as in the

doctor-patient model. Rather, the process

consultant works

to

develop relationships, observes groups

and people in action, helps them diagnose

the way they are

carrying

out tasks, and helps them

learn how to he more

effective.

In

the OD literature, team building is not

clearly differentiated from

process consultation. This

confusion

exists

because most team building

includes process consultation--helping

the group diagnose

and

understand

its own internal processes.

However, process consultation is a more

general approach to

helping

relationships than is team building.

Team building focuses

explicitly on helping groups

perform

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

tasks

and solve problems more

effectively. Process consultation, on the

other hand, is concerned

with

establishing

effective helping relationships in organizations. It

is seen as key to effective management

and

consultation

and can be applied to any

helping relationship, from subordinate development to

interpersonal

relationships

to group development. Thus, team

building consists of process consultation

plus other, more

task-oriented

interventions.

Group

Process:

Process

consultation deals primarily with

five important interpersonal and

group processes;

1.

communications,

2.

the functional roles of group

members,

3.

the ways in which the group

solves problems and makes

decisions,

4.

group norms development,

and

5.

The use of leadership and

authority.

Communications

One

of the process consultant's areas of

interest is the nature and

style of communication at both the

overt

and

covert levels. At the overt level, communication

issues involve who talks to

whom, for how long,

and

how

often. One method for

describing group communication is to keep

a time log of how often and

to

whom

people talk. For example, at an

hour-long meeting conducted by a

manager, the longest

anyone

other

than the manager got to

speak was one minute, and

that minute was allotted to

the assistant manager.

Rather

than telling the manager

that he is cutting people off, the

consultant can give descriptive

feedback

by

citing the number of times others

tried to talk and the amount of time they

were given. The consultant

must

make certain that the

feedback is descriptive and

not evaluative (good or bad), unless the

individual or

group

is ready for evaluative

feedback.

By

keeping a time log, the consultant also can

note who talks and

who interrupts. Frequently,

certain

people

are perceived as being quiet, when in fact they

have tried to say something

and have been

interrupted.

Such interruptions are one

of the most effective ways of reducing

communications and

decreasing

participation in a meeting.

Body

language and other nonverbal

behavior also can be a

highly informative method

for understanding

communication

processes. For example, at another

meeting conducted by a manager, the

animated

discussion

at the start of the meeting was

interrupted by the second-in-command, who

said, "This is a

problem-solving

meeting, not a gripe session." As the

manager continued to talk, the

fourteen other

members

present assumed expressions of

concentration. Within twenty-five

minutes, all of them

had

folded

their arms and were

leaning backward, a sure

sign that they were blocking

out or shutting off the

message.

Within ten seconds of the manager's

subsequent statement, "We

are interested in getting

your

ideas,"

those present unfolded their

arms and began to lean

forward, a clear nonverbal

sign that they were

involved

once again.

The

manager uses several

techniques to analyze the communications

processes in a work group.

Observe.

How

often and how long

does each member talk

during a group discussion?

These observations

can

be easily recorded on paper

and referred to later when analyzing

group behavior. It is also

useful to

keep

a record of who talks to

whom.

Identify.

Who

are the most influential

listeners in the group? Noticing

eye contact between members

can

give

insights on the communication processes.

Sometimes one person, and

perhaps not even the

person

who

speaks most frequently, is the

one focused on by others as they

speak.

Interruptions.

Who

interrupts whom? Is there a pattern in

the interruptions? What are the

apparent

effects

of the interruptions?

The

manager will probably share

this information with the group to

enable the members to better

understand

how they communicate with

one another.

Feedback

may be given intermittently during the

meeting or at the conclusion of the

meeting. The purpose

of

feedback is to enable group

members to learn about the way they

communicate with one

another.

At

the covert or hidden level of communication, sometimes

one thing is said but

another meant, thus

giving

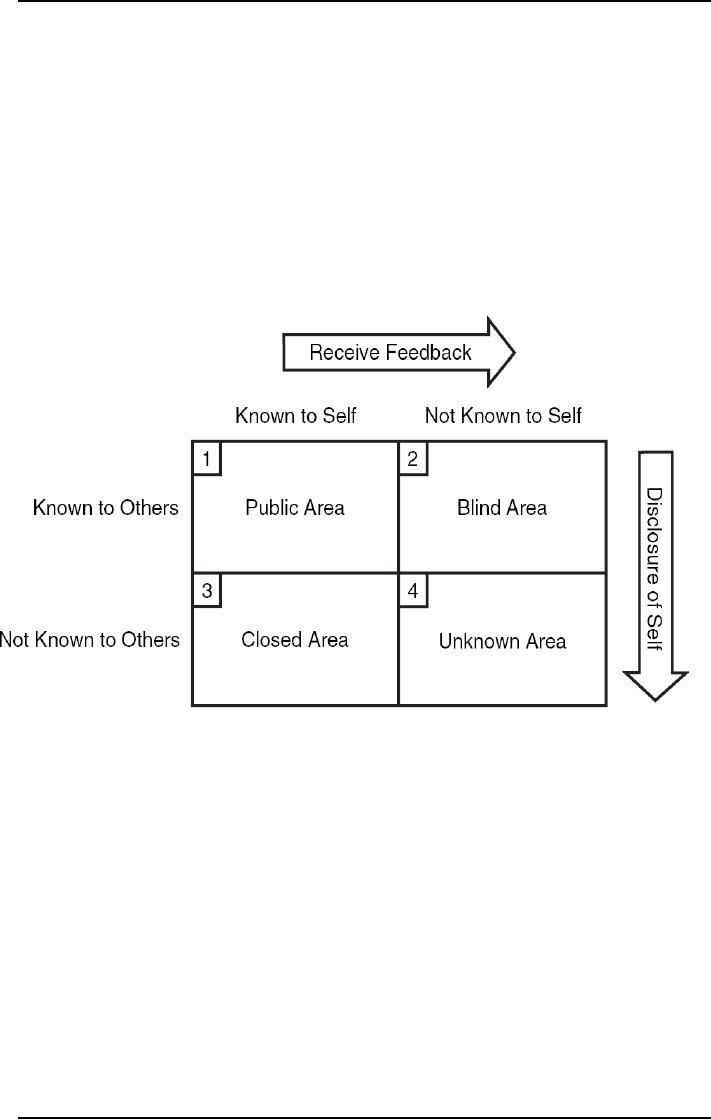

a double message. Luft has

described this phenomenon in what is called the

Johari Window. Figure

38,

a diagram of the Johari Window,

shows that some personal

issues are perceived by both

the individual

and

others (cell 1). Other

people are aware of their

own issues, but they conceal

them from others (cell

2).

People

with certain feelings about

themselves or others in the work

group may not share

with others unless

they

feel safe and protected; by not

revealing reactions they feel might be

hurtful or impolite, they

lessen

the

degree of communication.

Cell

3 comprises personal issues

that are unknown to the

individual but that are

communicated clearly to

others.

For example, an individual

may shout, "I'm not

angry," as he or she slams a

fist on the table, or

say,

"I'm

not embarrassed at all," as

lie or she blushes scarlet.

Typically, cell-3 communication conveys

double

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

messages.

For example, one manager

who made frequent business

trips invariably told his

staff to function

as

a team and to make decisions

in his absence. The staff, however

consistently refused to do this because

it

was

clear to them, and to the

process consultant, that the

manager was really saying,

"Go ahead as a team

and

make decisions in my absence,

but be absolutely certain they

are the exact decisions I

would make if I

were

here." Only after the manager

participated in several meetings in which

he received feedback was

he

able

to understand that he was

sending a double message. Thereafter, he

tried both to accept

decisions

made

by others and to use

management by objectives with

his staff and with

individual managers.

Cell

4 of the Johari Window represents

those personal aspects that

are unknown to either the individual

or

others.

Because such areas are

outside the realm of the process

consultant and the group, focus is

typically

on

the other three

cells.

The

consultant can encourage individuals to

be more open with others about

their views,

opinions,

concerns,

and emotions, thus reducing

cell 2. Further, the consultant can

help individuals give feedback

to

others,

thus reducing cell 3.

Reducing the size of these

two cells helps improve the

communication process

by

enlarging cell I, the "sell" that is open

to both the individual and

others.

Figure

38: Johari Window

Disclosure

and Feedback of Johari

Window:

As

indicated in Figure, movement along the vertical and

horizontal dimensions enables

individuals to

change

their interpersonal styles by increasing

the amount of communication in the public or shared

area.

To

enlarge the public area, a

person may move vertically by

reducing the closed area. As a

person behaves

less

defensively and becomes more

open, trusting and risk taking,

others will tend to react

with increased

openness

and trust. This process

termed, disclosure, involves the open

disclosure of one's

feelings,

thoughts

and candid feedback to

others. The openness of communication

leads more to open

and

congruent

relationships.

The

behavioral process used to enlarge the

public area horizontally

termed, feedback,

allows us to reduce

the

blind area. The only

way to become aware of our

blind spots is for others to

give information or

feedback

about our behavior.

The

blind area can only be

reduced with the help and

cooperation of others, and this requires

a willingness

to

invite and accept such

feedback.

Almost

every organization finds that

poor communication is the most important

problem preventing

organizational

effectiveness.

Table of Contents:

- The Challenge for Organizations:The Growth and Relevance of OD

- OD: A Unique Change Strategy:OD consultants utilize a behavioral science base

- What an “ideal” effective, healthy organization would look like?:

- The Evolution of OD:Laboratory Training, Likert Scale, Scoring and analysis,

- The Evolution of OD:Participative Management, Quality of Work Life, Strategic Change

- The Organization Culture:Adjustment to Cultural Norms, Psychological Contracts

- The Nature of Planned Change:Lewin’s Change Model, Case Example: British Airways

- Action Research Model:Termination of the OD Effort, Phases not Steps

- General Model of Planned Change:Entering and Contracting, Magnitude of Change

- The Organization Development Practitioner:External and Internal Practitioners

- Creating a Climate for Change:The Stabilizer Style, The Analyzer Style

- OD Practitioner Skills and Activities:Consultant’s Abilities, Marginality

- Professional Values:Professional Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, Technical Ineptness

- Entering and Contracting:Clarifying the Organizational Issue, Selecting an OD Practitioner

- Diagnosing Organizations:The Process, The Performance Gap, The Interview Data

- Organization as Open Systems:Equifinality, Diagnosing Organizational Systems

- Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Methods for Collecting Data, Observations

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Sampling, The Analysis of Data

- Designing Interventions:Readiness for Change, Techno-structural Interventions

- Leading and Managing Change:Motivating Change, The Life Cycle of Resistance to Change

- Leading and managing change:Describing the Core Ideology, Commitment Planning

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Measurement

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Research Design

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Group Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Leadership and Authority, Group Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Third-Party Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Building, Team Building Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Management Styles

- Organization Process Approaches:Application Stages, Microcosm Groups

- Restructuring Organizations:Structural Design, Process-Based Structures

- Restructuring Organizations:Downsizing, Application Stages, Reengineering

- Employee Involvement:Parallel Structures, Multiple-level committees

- Employee Involvement:Quality Circles, Total Quality Management

- Work Design:The Engineering Approach, Individual Differences, Vertical Loading

- Performance Management:Goal Setting, Management by Objectives, Criticism of MBO

- Developing and Assisting Members:Career Stages, Career Planning, Job Pathing

- Developing and Assisting Members:Culture and Values, Employee Assistance Programs

- Organization and Environment Relationships:Environmental Dimensions, Administrative Responses

- Organization Transformation:Sharing the Vision, Three kinds of Interventions

- The Behavioral Approach:The Deep Assumptions Approach

- Seven Practices of Successful Organizations:Training, Sharing Information