|

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

27

Evaluating

and Institutionalizing Organization

Development Interventions

Institutionalizing

interventions:

Once

it is determined that a change has

been implemented and is effective,

attention is directed at

institutionalizing

the changes--making them a permanent part of the

organization's normal functioning.

Lewin

described change as occurring in three

stages: unfreezing, moving, and

refreezing. Institutionalizing

an

OD intervention concerns refreezing. It

involves the long-term persistence of organizational

changes: to

the

extent that changes persist, they

can be said to be institutionalized.

Such changes are not

dependent on

any

one person but exist as a

part of the culture of an organization. This means

that numerous others

share

norms

about the appropriateness of the

changes.

How

planned changes become institutionalized

has not received much

attention in the OD literature.

Rapidly

changing environments have led to admonitions

from consultants and practitioners to

"change

constantly,"

to "change before you have

to," and "if it's not broke,

fix it anyway." Such a context

has

challenged

the utility of the institutionalization

concept. Why endeavor to make

any change permanent

given

that it may require changing

again soon? However, the admonitions

also have resulted in

institutionalization

concepts being applied in new ways.

Change itself has become the

focus of

institutionalization.

Total quality management, organization

learning, integrated strategic change,

and self-

design

interventions all are aimed

at enhancing the organization's capability for

change. In this vein,

processes

of institutionalization take on increased

utility. This section

presents a framework identifying

factors

and processes that

contribute to the institutionalization of OD

interventions, including the

process

of

change itself.

Institutionalization

Framework:

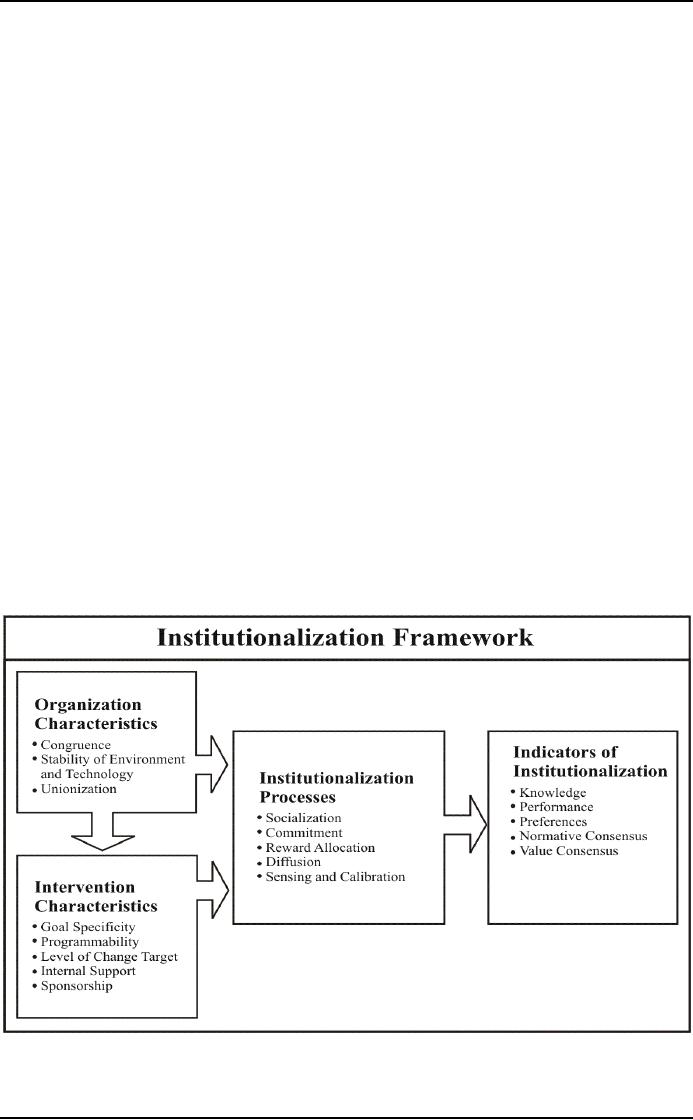

Figure

37 presents a framework that identifies

organization and intervention

characteristics and

institutionalization

processes affecting the degree to which

change programs are

institutionalized. The

model

shows that two key

antecedents--organization and intervention

characteristics--affect different

institutionalization

processes operating in organizations.

These processes, in turn, affect

various indicators

of

institutionalization. The model also

shows that organization characteristics

can influence intervention

characteristics.

For example, organizations having

powerful unions may have

trouble gaining internal

support

for OD interventions.

Figure

37: Institutionalization

Framework

Organization

Characteristics:

Figure

37 show that the following

three key dimensions of an organization

can affect intervention

characteristics

and institutionalization

processes.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

1.

Congruence. This

is the degree to which an intervention is

perceived as being in harmony with

the

organization's

managerial philosophy, strategy,

and structure; its current

environment; and other

changes

taking

place. When an intervention is congruent

with these dimensions, the

probability is improved that

it

will

be institutionalized. Congruence can

facilitate persistence by making it easier to

gain member

commitment

to the intervention and to diffuse it to

wider segments of the organization. The

converse also

is

true; many OD interventions promote

employee participation and

growth. When applied in

highly

bureaucratic

organizations with formalized structures

and autocratic managerial

styles, participative

interventions

are not perceived as congruent

with the organization's managerial

philosophy.

2.

Stability

of environment and technology: This

involves the degree to which the

organization's

environment

and technology are changing.

Unless the change target is

buffered from these changes

or

unless

the changes are dealt with

directly by the change program, it may be

difficult to achieve

long-term

intervention

stability. For example,

decreased demand for the

firm's products or services can

lead to

reductions

in personnel that may change

the composition of the groups involved in

the intervention.

Conversely,

increased product demand can

curtail institutionalization by bringing

new members on board

at

a rate faster than they can be

socialized effectively.

3.

Unionization.

Diffusion of interventions may be

more difficult in unionized

settings, especially if the

changes

affect union contract issues, such as

salary and fringe benefits,

ob design, and employee

flexibility.

For

example, a rigid union

contract can make it

difficult to merge several

job classifications into

one, as

might

be required to increase task variety in a

job enrichment program. It is important

to emphasize,

however,

that unions can be a powerful force

for promoting change, particularly

when a good relationship

exists

between union and

management.

Intervention

characteristics:

Figure

37 shows that the following

five major features of OD interventions

can affect institutionalization

processes:

1.

Goal

specificity. This involves the

extent to which intervention goals

are specific rather than

broad.

Specificity

of goals helps direct socializing

activities (for example. training

and orienting new members)

to

particular

behaviors required to implement the intervention. It

also helps operationalize the new

behaviors

so

that rewards can be linked

clearly to them. For

example, an intervention aimed

only at increasing

product

quality is likely to be more

focused and readily put into

operation than a change program

intended

to

improve quality, quantity,

safety, absenteeism, and

employee development.

2.

Programmability. This

involves the degree to which the changes

can be programmed or the extent to

which

the different intervention

characteristics can be specified

clearly in advance to enable

socialization,

commitment,

and reward allocation. For

example, job enrichment specifies

three targets of

change:

employee

discretion, task variety, and

feedback. The change program

can be planned and designed

to

promote

those specific

features.

3.

Level

of change target. This

concerns the extent to which the change

target is the total organization,

rather

than a department or small work group.

Each level of organization has facilitators

and inhibitors of

persistence.

Departmental and group changes

are susceptible to countervailing

forces from others in

the

organization.

These can reduce the

diffusion of the intervention and

lower its ability to impact

organization

effectiveness.

However, this does not

preclude institutionalizing the change

within a department that

successfully

insulates itself from the

rest of the organization. Such insulation

often manifests itself as

a

subculture

within the organization.

Targeting

the intervention to wider segments of the

organization, on the other hand, also

can help or

hinder

change persistence. A shared

belief about the intervention's value

can be a powerful incentive to

maintain

the change, and promoting a

consensus across organizational

departments exposed to the

change

can

facilitate institutionalization. But targeting the

larger system also can

inhibit institutionalization.

The

intervention

can become mired in political

resistance because of the "not

invented here" syndrome

or

because

powerful constituencies oppose

it.

4.

Internal

support. This

refers to the degree to which

there is an internal support system to

guide the

change

process. Internal support, typically

provided by an internal consultant,

can gain commitment for

the

changes

and help organization members implement

them. External consultants

also can provide

support,

especially

on a temporary basis during the early

stages of implementation. For example, in

many

interventions

aimed at implementing high--involvement

organizations, both external and

internal

consultants

provide change support. The external

consultant typically brings expertise on

organizational

design

and trains members to implement the

design. The internal consultant

generally helps members

relate

to

other organizational units, resolve conflicts

and legitimize the change activities

within the organization.

5.

Sponsorship. This

concerns the presence of a powerful

sponsor who can initiate,

allocate, and

legitimize

resources for the intervention.

Sponsors must come from

levels in the organization high

enough

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

to

control appropriate resources, and they

must have the visibility and

power to nurture the intervention

and

see that it remains viable. There

are many examples of OD

interventions that persisted

for several years

and

then collapsed abruptly when the

sponsor, usually a top administrator,

left the organization. There also

are

numerous examples of middle

managers withdrawing support for

interventions because

top

management

did not include them in the change

program.

Institutionalization

Processes:

The

framework depicted in Figure 37 shows the

following five institutionalization

processes that can

directly

affect the degree to which OD

interventions are

institutionalized.

1.

Socialization. This

concerns the transmission of information

about beliefs, preferences, norms,

and

values

with respect to the intervention.

Because implementation of OD

interventions generally involves

considerable

learning and experimentation, a continual

process of socialization is necessary to

promote

persistence

of the change program. Organization

members must focus attention

on the evolving nature of

the

intervention and its ongoing

meaning. They must communicate this

information to other

employees,

especially

new members. Transmission of

information about the intervention helps

bring new members

onboard

and allows participants to reaffirm the

beliefs, norms, and values

underlying the intervention.

For

example,

employee involvement programs

often include initial transmission of

information about the

intervention,

as well as retraining of existing participants

and training of new members.

Such processes are

intended

to promote persistence of the program as

both new behaviors are

learned and new members

are

introduced.

2.

Commitment. This binds people

to behaviors associated with the

intervention. It includes

initial

commitment

to the program, as well as recommitment over time.

Opportunities for commitment

should

allow

people to select the necessary behaviors

freely, explicitly, and

publicly. These conditions

favor high

commitment

and can promote stability of

the new behaviors. Commitment should derive

from several

organizational

levels, including the employees

directly involved and the

middle and upper managers

who

can

support or thwart the intervention. In

many early employee

involvement programs, for

example,

attention

was directed at gaining workers' commitment to

such programs. Unfortunately,

middle managers

were

often ignored and considerable

management resistance to the

interventions resulted.

3.

Reward

allocation. This

involves linking rewards to the new

behaviors required by an

intervention.

Organizational

rewards can enhance the

persistence of interventions in at least

two ways. First, a

combination

of intrinsic and extrinsic rewards

can reinforce new behaviors.

Intrinsic rewards are

internal

and

derive from the opportunities for

challenge, development, and

accomplishment found in the

work.

When

interventions provide these

opportunities, motivation to perform

should persist. This behavior

can

be

further reinforced by providing extrinsic

rewards, such as money, for

increased contributions.

Because

the

value of extrinsic rewards tends to

diminish over time, it may be

necessary to revise the reward

system

to

maintain high levels of desired

behaviors.

Second,

new behaviors will persist

to the extent that rewards are

perceived as equitable by

employees.

When

new behaviors are fairly

compensated. People are

likely to develop preferences for

those behaviors.

Over

time, those preferences should lead to

normative and value

consensus about the appropriateness

of

the

intervention. For example,

many employee involvement

programs fail to persist

because employees feel

that

their increased contributions to

organizational improvements are unfairly

rewarded. This is especially

true

for interventions relying

exclusively on intrinsic rewards.

People argue that an

intervention that

provides

opportunities for intrinsic

rewards also should provide

greater pay or extrinsic rewards

for higher

levels

of contribution to the organization.

4.

Diffusion. This

refers to the process of transferring

interventions from one

system to another.

Diffusion

facilitates

institutionalization by providing a wider

organizational base to support the new

behaviors. Many

interventions

fail to persist because they

run counter to the values and

norms of the larger organization.

Rather

than support the intervention, the

larger organization rejects the changes

and often puts pressure

on

the

change target to revert to old

behaviors. Diffusion of the intervention

to other organizational units

reduces

this counter implementation force. It tends to

lock in behaviors by providing

normative consensus

from

other parts of the organization.

Moreover, the act of transmitting

institutionalized behaviors to

other

systems

reinforces commitment to the

changes.

5.

Sensing

and calibration. This

involves detecting deviations from

desired intervention behaviors

and

taking

corrective action, institutionalized behaviors

invariably encounter destabilizing forces,

such as

changes

in the environment, new technologies,

and pressures from other

departments to nullify

changes.

These

factors cause some variation

in performances preferences norms,

and values. To detect this

variation

and

take corrective actions, organizations

must have some sensing

mechanism. Sensing mechanisms,

such

as

implementation feedback, provide

information about the occurrence of

deviations. This knowledge can

then

initiate corrective actions to ensure

that behaviors are more in

line with the intervention.

For example,

if

a high level of job discretion associated

with a job enrichment intervention

does not persist,

information

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

about

this problem might initiate' corrective

actions, such as renewed

attempts to socialize people or to

gain

commitment to the intervention.

Indicators

of Institutionalization:

Institutionalization

is not an all-or-nothing concept

but reflects degrees of

persistence of an intervention.

Figure

37 shows five indicators of the extent of an

intervention's persistence. The extent to

which the

following

factors arc present or

absent: indicates the degree of

Institutionalization

1.

Knowledge. This

involves the extent to which organization

members have knowledge of the

behaviors

associated

with an intervention, it is concerned

with whether members know enough to

perform the

behaviors

and to recognize the consequences of

that performance. For

example, job enrichment includes

a

number

of new behaviors, such as

performing a greater variety of tasks,

analyzing information about

task

performance,

and making decisions about

work methods and

plans.

2.

Performance. This is

concerned with the degree to

which intervention behaviors

are actually performed.

It

may be measured by counting the

proportion of relevant people performing the

behaviors. For

example,

60

percent of the employees in a particular

work unit might be

performing the job enrichment

behaviors

described

above. Another measure of

performance is the frequency with

which the new behaviors

are

performed.

In assessing frequency, it is important to

account for different variations of the

same essential

behavior,

as well as highly institutionalized

behaviors that need to be

performed only

infrequently.

3.

Preferences. This

involves the degree to which organization

members privately accept the

organizational

changes.

This contrasts with acceptance

based primarily organizational sanctions

or group pressures.

Private

acceptance usually is reflected in

people's positive attitudes

toward the changes and can

be

measured

by the direction and intensity of

those attitudes across the

members of the work unit

receiving

the

intervention. For example, a

questionnaire assessing members'

perceptions of a job enrichment

program

might show that most

employees have a strong

positive attitude toward making

decisions,

analyzing

feedback, and performing a variety of

tasks.

4.

Normative

consensus. This

focuses on the extent to which people

agree about the appropriateness

of

the

organizational changes. This indicator of

institutionalization reflects how

fully changes have

become

part

of the normative structure of the organization.

Changes persist to the degree

members feel that they

should

support them. For example, a

job enrichment program would become

institutionalized to the extent

that

employees support it and see it as appropriate to

organizational functioning.

5.

Value

consensus. This is

concerned with social

consensus on values relevant to the

organizational

changes.

Values are beliefs about how people

ought or ought not to

behave. They are

abstractions from

more

specific norms. Job enrichment,

for example, is based on

values promoting employee

self-control and

responsibility.

Different behaviors associated

with job enrichment, such as making

decision and

performing

a

variety of tasks, would persist to the

extent that employees widely

share values of self-control

and

responsibility.

These

five indicators can be used to

assess the level of institutionalization of an OD

intervention. The

more

the indicators are present in a situation, the higher

will be the degree of

institutionalization. Further;

these

factors seem to follow a

specific development order: knowledge, performance,

preferences, norms,

and

values. People must first

understand flew behaviors or

changes before they can perform

them

effectively.

Such performance generates

rewards and punishments,

which in time affect people's

preferences.

As many individuals come to

prefer the changes, normative

consensus about their

appropriateness

develops. Finally, if there is

normative agreement about the changes

reflecting a particular

set

of values, over time there should be

some consensus on those

values among organization

members.

Given

this developmental view of institutionalization, it is

implicit that whenever one

of the last indicators

is

present, all the previous ones

are automatically included as well. For

example, if employees

normatively

agree

with the behaviors associated

with job enrichment, then they

also have knowledge about the

behaviors,

can perform them effectively,

and prefer them. An OD

intervention is fully institutionalized

only

when

all five factors are

present.

Table of Contents:

- The Challenge for Organizations:The Growth and Relevance of OD

- OD: A Unique Change Strategy:OD consultants utilize a behavioral science base

- What an “ideal” effective, healthy organization would look like?:

- The Evolution of OD:Laboratory Training, Likert Scale, Scoring and analysis,

- The Evolution of OD:Participative Management, Quality of Work Life, Strategic Change

- The Organization Culture:Adjustment to Cultural Norms, Psychological Contracts

- The Nature of Planned Change:Lewin’s Change Model, Case Example: British Airways

- Action Research Model:Termination of the OD Effort, Phases not Steps

- General Model of Planned Change:Entering and Contracting, Magnitude of Change

- The Organization Development Practitioner:External and Internal Practitioners

- Creating a Climate for Change:The Stabilizer Style, The Analyzer Style

- OD Practitioner Skills and Activities:Consultant’s Abilities, Marginality

- Professional Values:Professional Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, Technical Ineptness

- Entering and Contracting:Clarifying the Organizational Issue, Selecting an OD Practitioner

- Diagnosing Organizations:The Process, The Performance Gap, The Interview Data

- Organization as Open Systems:Equifinality, Diagnosing Organizational Systems

- Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Methods for Collecting Data, Observations

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Sampling, The Analysis of Data

- Designing Interventions:Readiness for Change, Techno-structural Interventions

- Leading and Managing Change:Motivating Change, The Life Cycle of Resistance to Change

- Leading and managing change:Describing the Core Ideology, Commitment Planning

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Measurement

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Research Design

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Group Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Leadership and Authority, Group Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Third-Party Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Building, Team Building Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Management Styles

- Organization Process Approaches:Application Stages, Microcosm Groups

- Restructuring Organizations:Structural Design, Process-Based Structures

- Restructuring Organizations:Downsizing, Application Stages, Reengineering

- Employee Involvement:Parallel Structures, Multiple-level committees

- Employee Involvement:Quality Circles, Total Quality Management

- Work Design:The Engineering Approach, Individual Differences, Vertical Loading

- Performance Management:Goal Setting, Management by Objectives, Criticism of MBO

- Developing and Assisting Members:Career Stages, Career Planning, Job Pathing

- Developing and Assisting Members:Culture and Values, Employee Assistance Programs

- Organization and Environment Relationships:Environmental Dimensions, Administrative Responses

- Organization Transformation:Sharing the Vision, Three kinds of Interventions

- The Behavioral Approach:The Deep Assumptions Approach

- Seven Practices of Successful Organizations:Training, Sharing Information