|

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

26

Evaluating

and Institutionalizing Organization

Development Interventions

Measurement:

Providing

useful implementation and evaluation

feedback involves two

activities:

selecting

the appropriate variables and designing

good measures.

Selecting

Variables:

Ideally,

the variables measured in OD evaluation should derive

from the theory or conceptual

model

underlying

the intervention. The model should incorporate the

key features of the intervention as

well as its

expected

results. The general

diagnostic models described

earlier meet these criteria.

For example, the job-

level

diagnostic model proposes several major

features of work: task

variety, feedback, and

autonomy. The

theory

argues that high levels of

these elements can be

expected to result in high

levels of work quality

and

satisfaction.

In addition, as we shall see, the

strength of this relationship varies with

the degree of employee

growth

need: the higher the need, the more

that job enrichment produces

positive results.

The

job-level diagnostic model suggests a

number of measurement variables for

implementation and

evaluation

feedback. Whether the intervention is being

implemented could be assessed by determining

how

many

job descriptions have been

rewritten to include more responsibility or

how many organization

members

have received cross-training in

other job skills. Evaluation

of the immediate and long-

term

impact

of job enrichment would include measures

of employee performance and

satisfaction over time.

Again,

these measures would likely

be included in the initial diagnosis,

when the company's problems

or

areas

for improvement are

discovered.

Measuring

both intervention and

outcome variables is necessary

for implementation and

evaluation

feedback.

Unfortunately, there has

been a tendency in OD to measure

only outcome variables

while

neglecting

intervention variables altogether. It

generally is assumed that the

intervention has been

implemented

and attention, therefore, is directed to

its impact on such organizational

outcomes as

performance,

absenteeism, and satisfaction. As

argued earlier, implementing OD interventions

generally

take

considerable time and learning. It must

be empirically determined that the intervention

has been

implemented;

it cannot simply be assumed.

Implementation feedback serves this

purposes guiding the

implementation

process and helping to

interpret outcome data Outcome

measures are ambiguous

without

knowledge

of how well the intervention

has been implemented. For

example, a negligible change in

measures

of performance and satisfaction could

mean that the wrong

intervention has been

chosen, that

the

correct intervention has not

been implemented effectively, or that the

wrong variables have

been

measured.

Measurement of the intervention variables

helps determine the correct

interpretation of out-

come

measures.

As

suggested above, the choice of

intervention variables to measure should

derive from the conceptual

framework

underlying the OD intervention. OD

research and theory

increasingly have come to

identify

specific

organizational changes needed to implement particular

interventions. These variables should

guide

not

only implementation of the intervention

but also choices about what

change variables to measure

for

evaluative

purposes.

The

choice of what outcome variables to

measure also should be dictated by

intervention theory,

which

specifies

the kinds of results that can be

expected from particular change

programs. Again, the material

in

this

book and elsewhere identifies

numerous outcome measures,

such as job satisfaction,

intrinsic

motivation,

organizational commitment, absenteeism, turnover,

and productivity.

Historically,

OD assessment has focused on

attitudinal outcomes, such as

job satisfaction, while

neglecting

hard

measures, such as performance.

Increasingly, however, managers and

researchers are calling

for

development

of behavioral measures of OD outcomes.

Managers are interested

primarily in applying OD

to

change work-related behaviors that

involve joining, remaining, and

producing at work, and are

assessing

OD

more frequently in terms of

such bottom-line

results.

Designing

Good Measures:

Each

of the measurement methods described

earlier has advantages and

disadvantages. Many of

these

characteristics

are linked to the extent to which a

measurement is operationally defined, reliable,

and valid.

These

assessment characteristics are

discussed below.

1.

Operational

definition. A

good measure is operationally defined;

that is, it specifies the empirical

data

needed

how they will be collected

and, most important, how

they will be converted from data

to

information.

For example, Macy and Mirvis

developed operational definitions for the behavioral

outcomes

(see

Table 9). They consist of

specific computational rules that

can be used to construct

measures for each

of

the behaviors. Most of the behaviors

are reported as rates adjusted

for the number of employees in the

organization

and for the possible

incidents of behavior. These

adjustments make it possible to

compare the

measures

across different situations

and time periods. These operational

definitions should have wide

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

applicability

across both industrial and

service organizations, although

some modifications, deletions,

and

additions

may be necessary for a particular

application.

Operational

definitions are extremely

important in measurement because they

provide precise

guidelines

about

what characteristics of the situation are

to be observed and how they

are to he used. They tell

OD

practitioners

and the client system exactly

how diagnostic, intervention,

and outcome variables will

be

measured.

2.

Reliability.

Reliability concerns the extent to which

a measure represents the "true"

value of a variable;

that

is, how accurately the operational

definition translates data

into information. For

example, there is

little

doubt

about the accuracy of the number of cars leaving an

assembly line as a measure of

plant productivity;

although

it is possible to miscount, there

can be a high degree of confidence in the

measurement. On the

other

hand, when people are asked

to rate their level of job

satisfaction on a scale of 1 to 5, there

is

considerable

room for variation in their

response. They may just have

had an argument with

their

supervisor,

suffered an accident on the job, been

rewarded for high levels of

productivity, or been given

new

responsibilities. Each of these

events can sway the response

to the question on any given day.

The

individuals'

"true" satisfaction score is

difficult to discern from this

one question and the measure

lacks

reliability.

OD

practitioners can improve the reliability

of their measures in four

ways. First, rigorously and

operationally

define the chosen variables. Clearly

specified operational definitions

contribute to reliability

by

explicitly describing how

collected data will be converted

into information about a variable. An

explicit

description

helps to allay the client's

concerns about how the

information was collected

and coded. Second,

use

multiple methods to measure a particular

variable. The use of

questionnaires, interviews, observation,

and

unobtrusive measures can

improve reliability and

result in more comprehensive

understanding of the

organization.

Because each method contains

inherent biases, several

different methods can be

used to

triangulate

on dimensions of organizational problems. If the

independent measures converge or

show

consistent

results, the dimensions or problems

likely have been diagnosed

accurately.' Third, use

multiple

items

to measure the same variable on a

questionnaire. For example, in

Job Diagnostic Survey

for

measuring

job characteristics, the intervention

variable "autonomy" has the following

operational

definition:

the average of respondents' answers to

the following three questions

(measured on a seven--

point

scale):

1.

The job permits me to decide

on my own how to go about

doing the work.

2.

The job denies me any

chance to use my personal

initiative or judgment in carrying out

the work.

(Reverse

scored)

3.

The job gives me

considerable opportunity for

independence and freedom in how I do the

work.

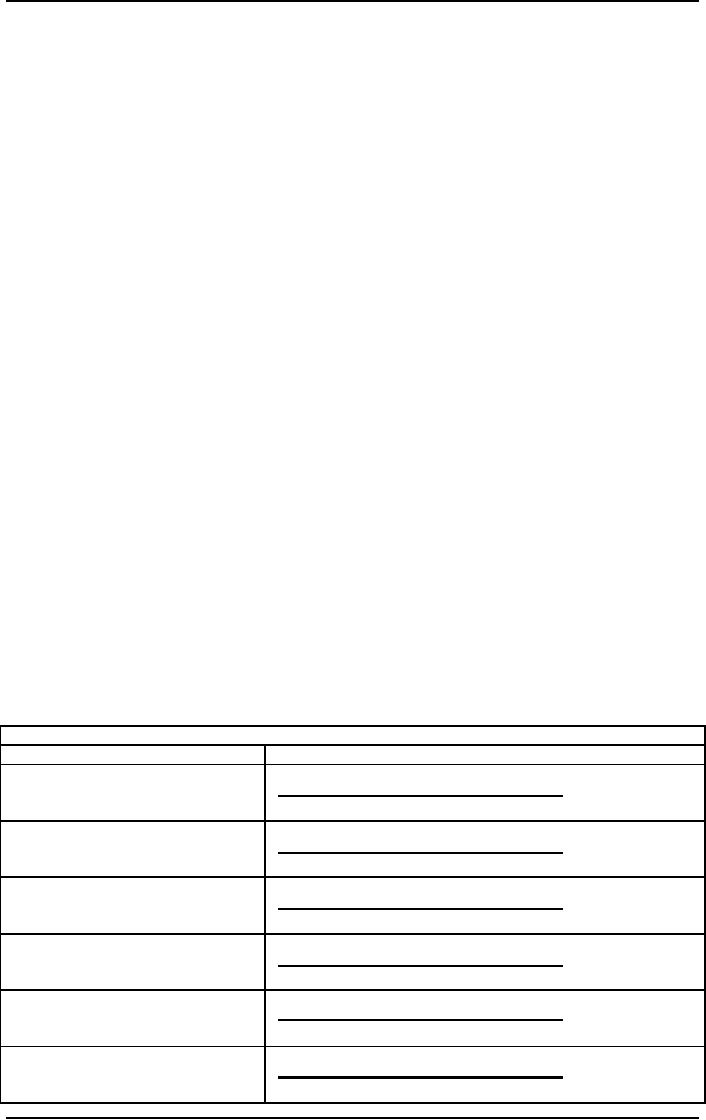

Table

9: Behavioral Outcomes for Measuring OD

Interventions: Measures and

Computational

Formulas

Behavioral

Outcomes for measuring OD Interventions:

Measures and Computational

Formulae

Behavioral

Measure

Computational

Formula

Absenteeism

rate (monthly)

∑

Absence

days

Average

workforce size x working

days

Turnover

rate (monthly

∑

Tardiness

incidents

Average

workforce size x working

days

Internal

stability rate

(monthly)

∑

Turnover

incidents

Average

workforce size

Strike

rate (yearly)

∑

Internal

movement incidents

Average

workforce size

Accident

rate (yearly)

∑

Striking

Workers x Strike days

Average

workforce size x working

days

Grievance

rate (yearly)

∑

of

Accidents, illnesses

X

200,000

Total

yearly hours worked

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

∑

Grievance

incidents

Plant:

Average

workforce size

∑

Aggrieved

individuals

Individual:

Average

workforce size x working

days

Productivity

Output

of goods or services (units or $)

Total

Direct

and/or indirect labor (hours

or $)

Below

standard

Actual

versus engineered

standard

Below

budget

Actual

versus budgeted

standard

Variance

Actual

versus budgeted

variance

Per

employee

Output/average

workforce size

Quality:

Scrap

+ customer returns + Rework

Recoveries ($, units or

Total

hours)

Below

standard

Actual

versus engineered

standard

Below

budget

Actual

versus budgeted

standard

Variance

Actual

versus budgeted

variance

Per

employee

Output/average

workforce size

Downtime

Labor

($) + Repair costs or dollar

value of replaced equipment

($)

Inventory,

supply and material

usage

Variance

(actual versus standard

utilization) ($)

By

asking more than one

question about "autonomy," time survey

increases the accuracy of

its

measurement

of this variable. Statistical analyses

(called psychometric tests)

are readily available

for

assessing

the reliability of perceptual measures,

and OD practitioners should apply these

methods or seek

assistance

from those who can apply

them.'' Similarly, there are methods

for analyzing the content of

interview

and observational data, and OD

evaluators can use these

methods to categorize such

information

so

that it can be understood and

replicated. Fourth, use

standardized instruments. A growing

number of

standardized

questionnaires are available

for measuring OD intervention

and outcome

variables.

3.

Validity.

Validity concerns the extent to which, a

measure actually reflects the variable it

is intended to

reflect.

For example, the number of cars leaving

an assembly line might be a reliable

measure of plant

productivity

but it may not be a valid

measure. The umber of cars

is only one aspect of

productivity; they

may

have been produced at an unacceptably

high cost. Because the number of

cars does not account

for

cost,

it is not a completely valid measure of

plant productivity.

OD

practitioners can increase the validity

of their measures in several

ways. First, ask colleagues

and clients

if

a proposed measure actually

represents a particular variable. This is

called face validity or

content validity.

If

experts and clients agree

that the measure reflects the variable of

interest, then there is

increased

confidence

in the measure's validity. Second,

use multiple measures of the

same variable, as described in

the

section

about reliability, to make preliminary

assessments of the measure's criterion or

convergent validity.

That

is, if several different

measures of the same variable correlate

highly with each other,

especially if one

or

more of the other measures

have been validated in prior

research, then there is

increased confidence in

the

measure's validity. A special

case of criterion validity,

called discriminant validity, exists

when the

proposed

measure does not correlate

with measures that it is not

supposed to correlate with.

For example,

there

is no good reason for daily

measures of assembly--line productivity to

correlate with daily air

temperature.

The lack of a correlation

would be one indicator that

the number of cars is measuring

productivity

and not some other variable.

Finally, predictive validity is

demonstrated when the variable of

interest

accurately forecasts another variable

over time. For example, a

measure of team cohesion can

be

said

to be valid if it accurately predicts

improvements in team performance in the

future.

It

is difficult, however, to establish the

validity of a measure until it

has been used. To address

this concern,

OD

practitioners should make heavy use of

content validity processes and

use measures that already

have

been

validated. For example, presenting

proposed measures to colleagues

and clients for evaluation

prior to

measurement

has several positive

effects: it builds ownership and commitment to the

data-collection

process

and improves the likelihood that the

client system will find the

data meaningful. Using measures

that

have been validated through

prior research improves confidence in the

results and provides a

standard

that

can be used to validate any

new measures used in collecting the

data.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Research

Design:

In

addition to measurement, OD practitioners

must make choices about how

to design the evaluation to

achieve

valid results. The key

issue is how to design the

assessment to show whether the

intervention did in

fact

produce the observed results.

This is called internal

validity. The secondary question of

whether the

intervention

would work similarly in other

situations is referred to as external validity.

External validity is

irrelevant

without first establishing an

intervention's primary effectiveness, so

internal validity is the

essential

minimum requirement for assessing OD

interventions. Unless managers

can have confidence

that

the

outcomes are the result of the

intervention, they have no rational

basis for making decisions

about

accountability

and resource allocation.

Assessing

the internal validity of an intervention

is, in effect, testing a

hypothesis--namely, that

specific

organizational

changes lead to certain

outcomes. Moreover, testing the

validity of an intervention

hypothesis

means that alternative hypotheses or

explanations of the results must be

rejected. That is, to

claim

that an intervention is successful, it is

necessary to demonstrate that

other explanations-- in the

form

of

rival hypotheses--do not

account for the observed

results. For example, if a

job enrichment program

appears

to increase employee performance,

such other possible explanations as

new technology, improved

raw

materials, or new employees

must be eliminated.

Accounting

for rival explanations is not a

precise, controlled, experimental process

such as might be

found

in

a research laboratory. OD interventions

often have a number of features

that make determining whether

they

produced observed results difficult.

They are complex and often

involve several interrelated

changes

that

obscure whether individual features or

combinations of features are accounting

for the results. Many

OD

interventions are long-term

projects and take

considerable time to produce desired

outcomes. The

longer

the time period of the change program,

the greater are the chances

that other factors, such

as

technology

improvements, will emerge to affect the

results. Finally, OD interventions

almost always are

applied

to existing work units rather than to

randomized groups of organization

members. Ruling out

alternative

explanations associated with randomly

selected intervention and

comparison groups is,

therefore,

difficult.

Given

the problems inherent in assessing OD

interventions, practitioners have turned

to quasi-

experimental

research designs. These

designs are not as rigorous

and controlled as are

randomized

experimental

designs, but they allow

evaluators to rule out many

rival explanations for OD results

other

than

the intervention itself, Although several

quasi-experimental designs are

available, those with

the

following

three features are particularly

powerful for assessing

changes:

1.

Longitudinal

measurement. This

involves measuring results

repeatedly over relatively long

time

periods.

Ideally, the data collection should

start before the change program is implemented

and continue

for

a period considered reasonable

for producing expected

results.

2.

Comparison

unit. It is

always desirable to compare

results in the intervention situation

with those in

another

situation where no such

change has taken place.

Although it is never possible to

get a matching

group

identical to tile intervention group,

most organizations include a number of

similar work units

that

can

be used for comparison

purposes.

3.

Statistical

analysis.

Whenever possible, statistical

methods should be used to rule out the

possibility

that

the results are caused by random

error or chance. Various

statistical techniques are

applicable to quasi-

experimental

designs, and OD practitioners should apply

these methods or seek help

from those who

can

apply

them.

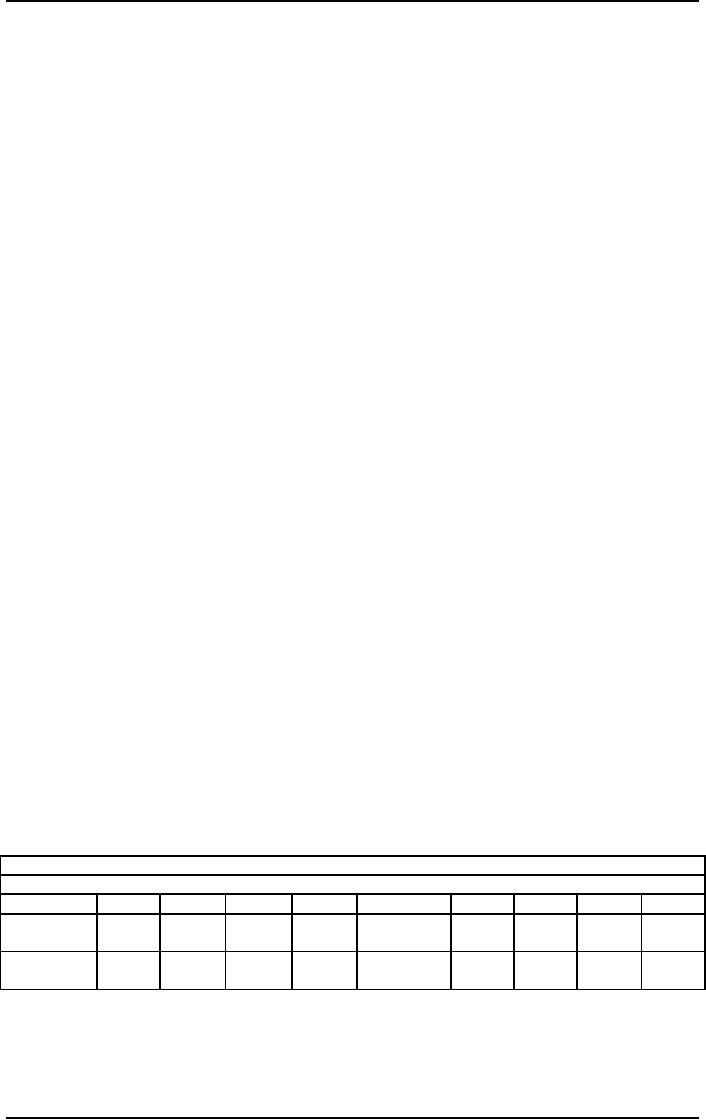

Table

10: Quasi Experimental

Research Design

Quasi-

Experimental Research

Design

Monthly

Absenteeism (%)

SEP.

OCT.

NOV.

DEC.

JAN

FEB

MAR

APR

Intervention

2.1

5.3

5.0

5.1

Start

of

4.6

4.0

3.9

3.5

group

intervention

Comparison

2.5

2.6

2.4

2.5

2.6

2.4

2.5

2.5

group

Table

10 provides an example of a quasi-experimental

design having these three

features. The

intervention

is

intended to reduce employee absenteeism.

Measures of absenteeism are

taken from company

monthly

records

for both the intervention

and comparison groups. The

two groups are similar

yet geographically

separate

subsidiaries of a multi-plant company.

Table 10 shows each plant's

monthly absenteeism rate

for

four

consecutive months both before and after

the start of the intervention. The

plant receiving the

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

intervention

shows a marked decrease in

absenteeism in the months following the

intervention, whereas

the

control plant shows

comparable levels of absenteeism in

both time periods. Statistical

analyses of these

data

suggest that the abrupt downward

shift in absenteeism following the

intervention was not

attributable

to

chance variation. This research

design and the data provide

relatively strong evidence that

the

intervention

was successful.

Quasi-experimental

research designs using

longitudinal data, comparison

groups, and statistical

analysis

permit

reasonable assessments of intervention

effectiveness. Repeated measures

often can be

collected

from

company records without

directly involving members of the

experimental and comparison

groups.

These

unobtrusive measures are

especially useful in OD assessment

because they do not interact with

the

intervention

and affect the results. More obtrusive

measures, such as questionnaires

and interviews, are

reactive

and can sensitize people to the

intervention. When this happens, it is

difficult to know whether the

observed

findings are the result of the

intervention, the measuring methods, or

some combination of

both.

Multiple

measures of intervention and

outcome variables should be applied to minimize

measurement and

intervention

interactions. For example, obtrusive

measures such as questionnaires could be

used sparingly,

perhaps

once before and once after the

intervention. Unobtrusive measures,

such as the behavioral

outcomes

shown in Table 9, could be used

repeatedly, thus providing a

more extensive time series

than the

questionnaires.

When used together the two kinds of

measures should produce accurate

and non-reactive

evaluations

of the intervention.

The

use of multiple measures

also is important in assessing

perceptual changes resulting from

intervention.

Considerable

research has identified

three types of change alpha,

beta, and gamma--that occur

when using

self-report,

perceptual measures.

Alpha

Change concerns

a difference that occurs along some

relatively stable dimension of reality.

This

change

is typically a comparative measure before

and after an intervention. For

example, comparative

measures

of perceived employee discretion might

show an increase after a job enrichment

program. If this

increase

represents alpha change, it

can be assumed that the job

enrichment program actually

increased

employee

perceptions of discretion.

If

comparative measures of trust among

team members showed an

increase after a team-building

intervention,

then we might conclude that

our OD intervention had made

a difference.

Beta

Change: Suppose,

however, that a decrease in trust

occurred or no change at all. One

study has

shown

that, although no decrease in trust

occurred, neither did a

measurable increase occur as

a

consequence

of team-building intervention. Change may

have occurred, however. The difference

may be

what

is called a beta change. As a

result of team-building intervention,

team members may view trust

very

differently.

Their basis for judging the

nature of trust changed, rather than

their perception of a simple

increase

or decrease in trust along some stable

continuum. This difference is called

beta change.

For

example, before-and-after measures of

perceived employee discretion can

decrease after a job

enrichment

program. If beta change is

involved; it can explain this apparent

failure of the intervention to

increase

discretion. The first measure of

discretion may accurately reflect the

individual's belief about the

ability

to move around and talk to fellow

workers in the immediate work

area. During implementation

of

the

job enrichment intervention, however, the

employee may learn that the

ability to move around is not

limited

to the immediate work area. At a

second measurement of discretion, the

employee, using this

new

and

recalibrated understanding, may

rate the current level of discretion as lower

than before.

Gamma

change involves

fundamentally redefining the measure as a

result of an OD intervention. In

essence,

the framework within which a phenomenon is

viewed changes. A major change in the

perspective

or

frame of reference occurs.

Staying with the example, after the

intervention team members

might

conclude

that trust was not a relevant variable in

their team building

experience. They might believe

that

the

gain in their clarity and responsibility

was the relevant factor and

their improvement as a team

had

nothing

to do with trust.

For

example, the presence of gamma

change would make it

difficult to compare measures of

employee

discretion

taken before and after a job enrichment

program. The measure taken after the

intervention

might

use the same words, but they

represent an entirely different

concept.

The

term "discretion" may originally refer to

the ability to move about the department and interact

with

other

workers. After the intervention,

discretion might be defined in terms of

the ability to make

decisions

about

work rules, work schedules,

and productivity levels. In

sum, the job enrichment intervention

changed

the

way discretion is perceived and

how it is evaluated.

These

three types of change apply to

perceptual measures. When

other than alpha changes

occur,

interpreting

measurement changes becomes the

more difficult. Potent OD

interventions may produce

both

beta

and gamma changes, which

severely complicates interpretations of

findings reporting change or

no

change.

Further, the distinctions among the three

different types of change

suggest that the heavy

reliance

on

questionnaires, so often cited in the

literature, should be balanced by using

other measures, such

as

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

interviews

and unobtrusive records.

Analytical methods have been

developed to assess the three kinds

of

change,

anti OD practitioners should gain

familiarity with these

recent techniques.

Case:

The Farm Bank

The

Farm Bank is one of the state's

oldest and most solid

banking institutions. Located in a

regional

marketing

center, the bank has been

active in all phases of banking,

specializing in farm loans. The

bank's

president,

Frank Swain, 62, has

been with the bank for many

years and is prominent in

local circles.

The

bank is organized into six

departments (as shown in Figure below). A

senior vice president heads

each

department.

All six of them have been

with the bank for years, and

in general they reflect a stable

and

conservative

outlook.

The

Management Information

System

Two

years ago, President Swain

felt that the bank needed to

"modernize its operations.

With the approval

of

the board of directors, he decided to

design and install a comprehensive

management information

system

(MIS). The primary goal was

to improve internal operations by supplying

necessary information on

a

more expedited basis, thereby decreasing

the time necessary to service customers.

The system was also

to

be

designed to provide economic operating

data for top management

planning and decision-making.

To

head

this department he selected Al Hassier,

58, a solid operations manager who

had some knowledge

and

experience

in the computer department.

After

the system was designed and

installed, Al hired a young woman as his

assistant. Valerie Wyatt was

a

young

MBA with a strong systems analysis

background. In addition to bring the only

woman and

considerably

younger than any of the other

managers at this level, Wyatt was the

only MBA.

In

the time since the system was

installed, the MIS has

printed thousands of pages of

operating

information,

including reports to all the vice

presidents, all the branch

managers, and the president.

The

reports

include weekly, monthly, and quarterly

summaries and include cost of

productions, projected labor

costs,

overhead costs, and projected

earnings figures for each

segment of the bank's

operations.

The

MIS Survey

Swain

was pleased with the system

but noticed little improvement in

management operations. In fact,

most

of

the older vice presidents

were making decisions and

function pretty much as they

did before the MIS

was

installed. Swain decided to

have Wyatt conduct a survey of the users

to try to evaluate the impact

and

benefits

of the new system. Wyatt was

glad to undertake the survey,

because she had long

felt the system

was

too elaborate for the bank's

needs. She sent out a

questionnaire to all department heads,

branch

managers,

and so on, inquiring into

their uses of the

system.

As

she began to assemble the

survey data, a pattern began to

emerge. In general, most of the

managers

were

strongly in favor of the system but

felt that it should be modified. As Wyatt

analyzed the responses,

several

trends and important points

came out: (1) 93 percent

reported that they did not regularly

use the

reports

because the information was

not in a useful form, (2) 76

percent reported that the printouts

were

hard

to interpret, (3) 72 percent

stated that they received

more data than they wanted,

(4) 57 percent

reported

finding some errors and

inaccuracies, and (5) 87

percent stated that they

still kept manual

records

because

they did not fully trust the

MIS.

The

Meeting

Valerie

Wyatt finished her report, excitedly

rushed into Al Hassler's

office, and handed it to

him. Hassler

slowly

scanned the report and then

said, "You've done a good

job here, Val. But

now that we have the

system

operating, I don't think we should upset

the apple cart, do you? Let's just

keep this to ourselves

for

the

time being, and perhaps we

can correct most of these

problems. I'm sure Frank

wouldn't want to hear

this

kind of stuff. This system

is his baby, so maybe we shouldn't

rock the boat with this

report."

Valeries

returned to her office feeling uncomfortable.

She wondered what to do.

Case

Analysis Form

Name:

____________________________________________

I.

Problems

A.

Macro

1.

____________________________________________________

2.

____________________________________________________

B.

Micro

1.

_____________________________________________________

2.

_____________________________________________________

II.

Causes

1.

_____________________________________________________

2.

_____________________________________________________

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

3.

_____________________________________________________

III.

Systems affected

1.

Structural

____________________________________________

2.

Psychosocial

__________________________________________.

3.

Technical

______________________________________________

4.

Managerial

_____________________________________________

5.

Goals

and values

__________________________________________

IV.

Alternatives

1.

_________________________________________________________

2.

_________________________________________________________

3.

________________________________________________________

V.

Recommendations

1.

_________________________________________________________

2.

__________________________________________________________

3.

__________________________________________________________

Case

Solution: The Farm

Bank

I.

Problems

A.

Macro

1.

Client

system unprepared for

change.

2.

Client

system unfamiliar with and

unprepared for MIS.

B.

Micro

1.

Top-down

approach (Swain's) excluded staff

from decision and preparation

for MIS.

2.

Survey

should have preceded, not

followed, MIS.

3.

Hassler

not assertive enough to fulfill

Swain's goals by keeping Swain

informed.

4.

Particulars

in MIS need to be changed

(limit info after determining needs,

change format, etc.).

5.

Valarie

Wyatt has been charged by

Swain to make survey but

her boss, Hassler, has

told her not to

give

the report to Swain.

II.

Causes

1.

Conservative

nature of firm (and age of

staff).

2.

Lack

of education regarding MIS.

3.

Lack

of planning regarding functions

MIS would perform for

managers and firm.

4.

Hassler

more interested in personal

security than in fulfilling

purpose for which he was

hired.

III.

Systems affected

1.

Structural

- Chain of command prohibited Wyatt from

improving MIS through using

results of

report.

2.

Technical

- MIS needs new form

and new limitations. These

are not being carried

out.

3.

Behavioral

Wyatt's "fulfillment" and

satisfaction of job well done

are restricted. Other

staff's

expectations

brought on by survey are frustrated by

lack of follow-through. Swain

hopes are not

fulfilled.

Hassler knows, somewhere, he is

not fulfilling his role. Managerial

decisions company-

wide

are not being made in the

best possible way, since

information is not being managed in

the

most

effective way possible.

4.

Managerial

Hassler is uncomfortable about

taking things up the chain. Possibly the

president,

Frank

Swain, has intimidated

subordinates in the past. Or Hassler

does not want to rock the

boat,

has

a "full plate", or maybe is

lazy. It is difficult to access

motives of managers.

5.

Goals

and values Excellence

and organization improvement does

not seem to be valued by

most

managers

except possibly

Wyatt.

IV.

Alternatives

1.

Wyatt

could convince Hassler it's in his best

interest to show Swain

results of survey.

2.

Wyatt

could go along with Hassler's

inaction.

3.

Wyatt

could go around Hassler and tell

Swain.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

V.

Recommendations

Wyatt

needs to submit the report to Swain

since this is the person who

assigned her to do the survey.

She

needs

to explain tactfully to Hassler the importance of

her giving Swain the report.

Once the report is

sent

to

Swain, The Farm Bank needs

to embark on a strategy of solving the

problems identified in the

survey.

The

approach should be an integrated one

involving the people who use the

MIS with them

identifying

specific

problems and the steps to

correct the problems. Hassler

needs to be involved in making the

changes

as well as Wyatt.

Table of Contents:

- The Challenge for Organizations:The Growth and Relevance of OD

- OD: A Unique Change Strategy:OD consultants utilize a behavioral science base

- What an “ideal” effective, healthy organization would look like?:

- The Evolution of OD:Laboratory Training, Likert Scale, Scoring and analysis,

- The Evolution of OD:Participative Management, Quality of Work Life, Strategic Change

- The Organization Culture:Adjustment to Cultural Norms, Psychological Contracts

- The Nature of Planned Change:Lewin’s Change Model, Case Example: British Airways

- Action Research Model:Termination of the OD Effort, Phases not Steps

- General Model of Planned Change:Entering and Contracting, Magnitude of Change

- The Organization Development Practitioner:External and Internal Practitioners

- Creating a Climate for Change:The Stabilizer Style, The Analyzer Style

- OD Practitioner Skills and Activities:Consultant’s Abilities, Marginality

- Professional Values:Professional Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, Technical Ineptness

- Entering and Contracting:Clarifying the Organizational Issue, Selecting an OD Practitioner

- Diagnosing Organizations:The Process, The Performance Gap, The Interview Data

- Organization as Open Systems:Equifinality, Diagnosing Organizational Systems

- Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Methods for Collecting Data, Observations

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Sampling, The Analysis of Data

- Designing Interventions:Readiness for Change, Techno-structural Interventions

- Leading and Managing Change:Motivating Change, The Life Cycle of Resistance to Change

- Leading and managing change:Describing the Core Ideology, Commitment Planning

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Measurement

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Research Design

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Group Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Leadership and Authority, Group Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Third-Party Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Building, Team Building Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Management Styles

- Organization Process Approaches:Application Stages, Microcosm Groups

- Restructuring Organizations:Structural Design, Process-Based Structures

- Restructuring Organizations:Downsizing, Application Stages, Reengineering

- Employee Involvement:Parallel Structures, Multiple-level committees

- Employee Involvement:Quality Circles, Total Quality Management

- Work Design:The Engineering Approach, Individual Differences, Vertical Loading

- Performance Management:Goal Setting, Management by Objectives, Criticism of MBO

- Developing and Assisting Members:Career Stages, Career Planning, Job Pathing

- Developing and Assisting Members:Culture and Values, Employee Assistance Programs

- Organization and Environment Relationships:Environmental Dimensions, Administrative Responses

- Organization Transformation:Sharing the Vision, Three kinds of Interventions

- The Behavioral Approach:The Deep Assumptions Approach

- Seven Practices of Successful Organizations:Training, Sharing Information