|

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

23

Leading

and Managing Change

After

diagnosis reveals the cause of

problem or opportunities for development,

organization members

begin

planning and subsequently

leading and implementing the changes

necessary to improve organization

effectiveness

and performance. A large

part of OD is concerned with

interventions for

improving

organization.

Changes

can vary in complexity from the

introduction of relatively simple process

into a small work

group

to

transformation the strategies and

design features of the whole

organization. Although change

management

differs across situation, here we

discuss tasks that must be

performed in managing any

kind of

organization

change.

Overview

of Changes Activities:

The

OD literature has directed considerable

attention to leading and

managing change. Much of

the

material

is highly prescriptive, advising mangers

about how to plan and implement

organizational changes.

Traditionally,

change management has

focused on identifying sources of

resistance to change and

offering

ways

to overcome them. More

recent contribution has

challenged the focus on resistance

and has been

aimed

at creating vision and

desired future, gaining political

support for them, and

managing the transition

of

the organization toward them.

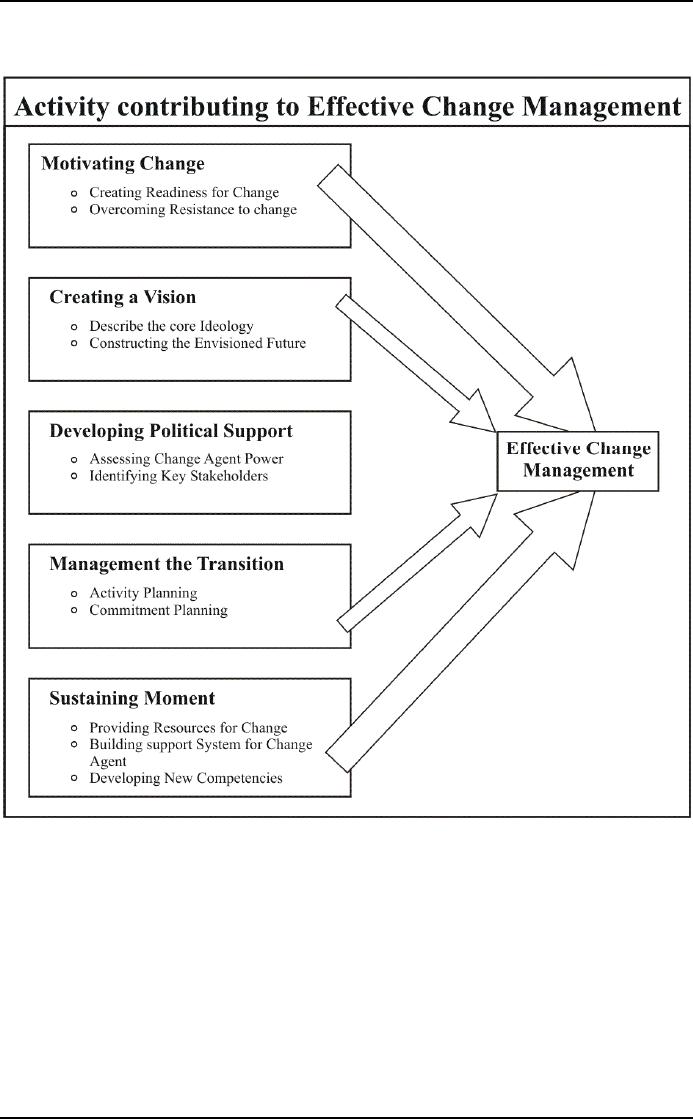

The

diversity of practical advice for

managing change can be

organized into five major

activities, as shown

in

figure 33. The activities

contribute to effective change management

and are listed roughly in the

order in

which

they typically are performed. Each

activity represents a key

element in change leadership.

The first

activity

involves motivating change

and includes creating a

readiness for change among

organization

member

and helping them address

resistance to change. Leadership

must create an environment in

which

people

accept the need for change

and commit physical and

psychological energy to it.

Motivation is a

critical

issue in starting change because

ample evidence indicates

that people and organization seek

to

preserve

the status quo and are

willing to change only when

there is compelling reason to do so.

The

second

activity is concerned with

creating a vision and is

closely aligned with

leadership activities.

The

vision

provides a purpose and reason

for change and describes the

desired future state.

Together, they

provide

the "why" and "what" of planned

change. The third activity

involves developing political

support

for

change. Organizations are

composed of powerful individuals

and groups that can either

block or

promote

change. The fourth activity

is concerned with managing the

transition from the current state

to

the

desired future state. It involves

creating a plan for managing

the change activities as well as

planning

special

management structure for operating the

organization during the transition. The

fifth activity

involves

sustaining momentum for change so

that it will be carried to

completion. This includes

providing

resources

for implementation the changes,

building a support system

for change agent, developing

new

competencies

and skills, and reinforcing

the new behaviors needed to implement the

changes.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Figure

33. Activity Contributing to

Effective Change

Management

Each

of the activities shown in Figure 33 is

important for managing

change. Although little

research has

been

conducted on their relative

contributions, organization leaders must

give careful attention to

each

activity

when planning and implementing organizational

change. Unless individuals

are motivated and

committed

to change, unfreezing the status quo

will be extremely difficult. In the

absence of vision,

change

is

likely to be disorganized and diffuse.

Without the support of powerful

individuals and groups,

change

may

be blocked and possibly sabotaged.

Unless the transition process is

managed carefully, the organization

will

have difficulty functioning

while it moves from the current

state to the future state.

Without efforts to

sustain

momentum for change, the organization

will have problems carrying

the changes through to

completion.

Thus, all five activities

must be managed effectively to

realize success.

Let's

now discuss more fully

each of these change

activities, directing attention to how

the activities

contribute

to planning and implementing organizational

change.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Motivating

Change:

Organizational

change involves moving from

the known to the unknown. Because the

future is uncertain

and

may adversely affect people's

competencies, worth and coping abilities,

organization members generally

do

not support change unless

compelling reason convince them to do so. Similarly,

organizations tend to

be

heavily invested in the status quo, and

they resist changing it in the face of

uncertain future benefits.

Consequently,

a key issue in planning for

action is how to motivate commitment to organizational

change.

As

shown in figure 33, this

requires attention to two

related tasks: creating

readiness for change

and

overcoming

resistance to change.

Creating

Readiness for

Change:

One

of the more fundamental axioms of OD is

that people's readiness for

change depends on creating

a

felt

need for change. This

involves making people so dissatisfied

with the status quo that

they are motivated

to

try new work process,

technology, or ways of behaving. Creating

such dissatisfaction can be

difficult, as

any

one knows who has tried to

lose weight, stop smoking, or

change some other habitual

behavior.

Generally,

people and organizations need to

experience deep levels of

hurt before they will

seriously

undertake

meaningful change. For example

IBM, GM and Sears

experienced threats to their very

survival

before

they undertook significant change

program. The following three

methods can help

generate

sufficient

dissatisfaction to produce

change:

1.

Sensitize

organizations to pressure for change.

Innumerable

pressures for change operate

both

externally

and internally to organizations. As

mentioned earlier, modern organizations

face

unprecedented

environmental pressures to change

themselves, including heavy

foreign

competition,

rapidly changing technology,

and the draw of global

markets. Internally pressures

to

change

include new leadership, poor

product quality, high

production costs and

excessive

employee

absenteeism and turnover. Before

these pressures can serve as

triggers for change,

however,

organizations must be sensitive to

them. The pressure must

pass beyond an

organization's

threshold of awareness if managers are to

respond to them. Many

organizations,

such

as Kodak, Apple, Polaroid

and Jenny Craig, set

their threshold of awareness too

high and

neglected

pressure for changes until

those pressures reached

disastrous levels. Organizations

can

make

themselves more sensitive to

pressure for change by

encouraging leaders to surround

themselves

with devil's advocate; by cultivating

external network that comprise people

or

organizations

with different perspective

and views; by visiting other

organizations to gain

exposure

to

new ideas and methods;

and by using external standards of

performance, such as competitions'

progress

or benchmarks, rather than the organization's

own past standards of

performance.

2.

Reveal

discrepancies between current and

desired states. In this

approach to generating a

felt

need for change, information

about the organization's current functioning is

gathered and

compared

with desired states of operation.

(See "Creating a Vision"

later for more

information

about

desired future states.)

These desired states may

include organizational goals and

standards,

as

well as general vision of a

more desirable future state.

Significant discrepancies between

actual

and

ideal states can motivate

organization members to initiate corrective

changes, particularly

when

members are committed to achieving

those ideals. A major goal of

diagnosis, as described

earlier,

is to provide members with

feedback about current organizational functioning so

that the

information

can be compared with goals

or with desired function

states. Such feedback

can

energize

action to improve the organization.

3.

Convey

credible positive expectation

for the change. Organization

members invariably

have

expectations

about the result of organizational changes.

The contemporary approach to

planned

change

described earlier suggest

that these expectations can

play an important role in

generating

motivation

for change. The expectations

can serve as a fulfilling prophecy,

leading members to

invest

energy in changes program that they

expect will succeed. When

members expect

success,

they

are likely to develop greater commitment

to the change process and to direct

more energy

into

the constructive behaviors needed to implement

it. The key to achieving

these positive

effects

is to communicate realistic, positive

expectation about the organizational changes.

Organization

members also can be taught about the

benefit of positive expectations

and be

encouraged

to set credible positive expectations

for the change

program.

Overcoming

Resistance to Change:

Change

can generate deep resistance

in people and in organization, thus making it

difficulty, if not

possible,

to

implement organizational improvement. At a personal level,

change can arouse

considerable anxiety

about

letting go of the known and

moving to an uncertain future. People

may be unsure whether

their

existing

skills and contribution will

be valued in the future, or have significant

questions about whether they

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

can

learn to function effectively

and to achieve benefits in the

new situation. At the organization level,

resistance

to change can come from

three sources. Technical

resistance comes from the

habit of following

common

producers and the consideration of sunk

costs invested in the status quo.

Political resistance

can

arise

when organization changes threaten powerful

stakeholders, such as top

executive or staff personal, or

call

into question the past decisions of

leaders. Organization change often

implies a different allocation of

already

scare resources, such as

capital, training budgets

and good people. Finally cultural

resistance takes

the

form of systems and

procedures that reinforce the status quo,

promoting conformity to existing

values,

norms,

and assumptions about how

things should operate.

There

are at least three major

strategies for dealing with

resistance to change.

1.

Empathy

and support. A

first step in overcoming resistance is to

learn how people are

experiencing

change. This strategy can

identify people who are having

trouble accepting the

changes,

the nature of their resistance,

and possible ways to

overcome it, but it requires

a great deal

of

empathy and support. It demands

willingness to suspend judgment and to

see the situation from

another's

perspective, a process called

active listening. When people feel that

those people who are

responsible

for managing change are

genuinely interested in their feelings

and perception, they are

likely

to be less defensive and

more willing to share their

concern and fears. This

more open

relationship

not only provides useful

information about resistance

but also helps establish the

basis

for

the kind of joint problem solving

needed to overcome barriers to

change.

2.

Communication.

People

resist change when they are uncertain

about its consequences. Lack of

adequate

information fuels rumors and

gossip and adds to the anxiety

generally associated

with

change.

Effective communication about changes

and their likely result

can reduce this

speculation

and

allay unfounded fears. It

can help members

realistically prepare for

change.

However,

communication is also one of the most

frustrating aspects of managing

change.

Organization

members constantly receive data

about people, changes and politics.

Managers and

OD

practitioners must think seriously about

how to break through this

stream of information.

One

strategy is to make change

information salient by communicating

through a new

different

channel.

If most information is delivered through

memos and emails, the change

information can

be

sent through meeting and

presentations. Another method that

can be effective during

large-

scale

change is to substitute change

information for normal operating

information deliberately.

This

sends a message that

changing one's activities is a critical

part of a member's

job.

3.

Participation

and involvement. One of the

oldest and most effective

strategies for overcoming

resistance

is to involve organization members directly in

planning and implementing

change.

Participation

can lead both to designing

high quality changes and to

overcoming resistance to

implementing

them. Members can provide a

diversity of information and ideas,

which can

contribute

to making the innovations effective and appropriate to

the situation. They also

can

identify

pitfalls and barriers to implementation.

Involvement in planning the changes

increases the

likelihood

that members' interest and

needs will be accounted for

during the intervention.

Consequently,

participants will be committed to implementing the

changes because doing so

will

suit

their interests and meet

their needs. Moreover, for

people having strong needs for

involvement,

the act of participation itself

can be motivating, leading to

greater effort to make

the

changes

work.

The

Life Cycle of Resistance to

Change:

Organization

programs such as downsizing,

reengineering and total

quality management

involve

innovations

and changes that will

probably encounter some degree of

resistance. This resistance

will be

evident

in individuals and groups in

such forms as controversy, hostility, and

conflict, either overt or

covert.

The response to change tends

to move through a life

cycle.

Phase

1

In

the first phase, there are

only a few people who see the

need for change and

take reform seriously, As

a

fringe

element of the organization, they may be

openly criticized, ridiculed, and

persecuted by whatever

methods

the organization has at its disposal

and thinks appropriate to handle

dissidents and force them to

conform

to established organizational norms. The

resistance looks massive. At this

point the change

program

may die, or it may continue to

grow. Large organizations

seem to have more difficulty

bringing

about

change than smaller

organizations. One of IBM's business

partners has said, for

example, that trying

to

get action from IBM is like

swimming through "giant pools of

peanut butter."

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Phase

2

As

the movement for change begins to grow

the forces for and against

it become identifiable. The

change

is

discussed, and is more

thoroughly understood by more of the

organizations members. Greater

understanding

may lessen the perceived threat of the

change. In time, the novelty and

strangeness of the

change

tends to disappear.

Phase

3

In

this phase there is a direct conflict

and showdown between the forces

for and against the change.

This

phase

will probably mean life or

death to the change effort,

because the exponents of the change

often

underestimate

the strength of their opponents. Those in

organization who see change as

good and needed

often

find it difficult to believe

how far the opposition will

go to put a stop to the

change.

Phase

4

If

the supporters of the change are in power

after the decisive battles, they will see

the remaining resistance

as

stubborn and a nuisance. There is

still a possibility that the

resisters will mobilize enough

support to shift

the

balance of power. Wisdom is

necessary in dealing with

overt opposition and also

with the sizable

element

that are not openly

opposed to the change but

also not convinced of its

benefits.

Phase

5

In

the last phase, the resisters to the

change are as few and as

alienated as the advocates were in the

first

phase.

Although the description of the five

phases may give the

impression that a battle is being

waged

between

those trying to bring about

change and those resisting

the change (and sometimes this is

the

situation),

the actual conflict is usually

more subtle and may

only surface in small verbal

disagreements,

questions,

reluctance, and so

forth.

To

better understand the phases, see the

Five Phases of Resistance to

Change in Action.

Regardless

of how much resistance there

is to the organizations change program,

the change will to

some

extent

evolve through the five phases

described above.

Depending

on the change program, however, some of

the phases may be brief,

omitted, or repeated. If the

last

phase is not solidified, the

change process will move

into first phase again.

General Electric's retired

CEO,

John F. Welch, has

written:

People

always ask, "Is the change

over? Can we stop now? "

You've got to tell them,

"No, it's just begun."

They

must come to understand that

it is never ending. Leaders must

create an atmosphere where

people

understand

that change is continuing

process, not an

event.

The

Five Phases of Resistance to

Change

Phase

1

In

the 1970s the environmental movement

began to grow. The First

Earth Day was held in

1970.

Widespread

interest in environmental concerns

subsided during the 1980s.

Some political

officials

neglected

environmental concerns, and

environmentalists were often portrayed as

extremists and

radicals

(even

antidevelopment). The forces for

change were small, but

pressure for change

persisted through

court

actions,

elected officials, and group

actions.

Phase

2

Environmental

supporters and opponents became

more identifiable in the 1980s.

Secretary of the Interior

James

Watt was perhaps the most

vocal and visible opponent of

environmental concerns and

served as a

"lightening

rod" for pro-environmental

forces like the Sierra Club

and the Wilderness Society. As

time

passed,

educational efforts by environmental

groups increasingly delivered their

message. The public

now

has

information and scientific data

that enabled it to understand the

problem.

Phase

3

The

Clean Air Act passed by

Congress in 1990 represented the

culmination of years of

confrontation

between

pro- and anti-environmental

forces. The bill was

passed several months after national

and

worldwide

Earth Day events. Corporations criticized

for contributing to environmental

problems took out

large

newspaper and television ads to explain

how they were reducing

pollution and cleaning up

the

environment.

The "greening" of corporations became

very popular.

Phase

4

One

example is the confrontation between

Greenpeace (an environmental

group) and Shell Oil.

The

Greenpeace

group had been campaigning

for weeks to block the Royal

Dutch/Shell group from

disposing

of

the towering Brent Spar

oil-storage rig by sinking it deep in the

Atlantic Ocean. As a small

helicopter

sought

to land Greenpeace protesters on the

rig's deck, Shell blasted

high-powered water canons to

fend

off

the aircraft. This was all captured on

film and shown on TV around the

world. Four days after

the

incident,

Shell executives made a

humiliating about-face; they agreed to

comply with Greenpeace

requests

and

dispose of the Brent Spar on land.

The incident, like the Exxon

Valdez oil spill, shows how

high-

profile

cases can ignite worldwide

public interest.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Phase

5

Much

of the world now sees

environmentally responsible behavior as a

necessity. Near-zero automobile

emissions

are moving closer to a

reality. Recycling has

become a natural part of everyday

life for many

people.

But new ways to be

environmentally responsible are

still being sought.

Table of Contents:

- The Challenge for Organizations:The Growth and Relevance of OD

- OD: A Unique Change Strategy:OD consultants utilize a behavioral science base

- What an “ideal” effective, healthy organization would look like?:

- The Evolution of OD:Laboratory Training, Likert Scale, Scoring and analysis,

- The Evolution of OD:Participative Management, Quality of Work Life, Strategic Change

- The Organization Culture:Adjustment to Cultural Norms, Psychological Contracts

- The Nature of Planned Change:Lewin’s Change Model, Case Example: British Airways

- Action Research Model:Termination of the OD Effort, Phases not Steps

- General Model of Planned Change:Entering and Contracting, Magnitude of Change

- The Organization Development Practitioner:External and Internal Practitioners

- Creating a Climate for Change:The Stabilizer Style, The Analyzer Style

- OD Practitioner Skills and Activities:Consultant’s Abilities, Marginality

- Professional Values:Professional Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, Technical Ineptness

- Entering and Contracting:Clarifying the Organizational Issue, Selecting an OD Practitioner

- Diagnosing Organizations:The Process, The Performance Gap, The Interview Data

- Organization as Open Systems:Equifinality, Diagnosing Organizational Systems

- Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Methods for Collecting Data, Observations

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Sampling, The Analysis of Data

- Designing Interventions:Readiness for Change, Techno-structural Interventions

- Leading and Managing Change:Motivating Change, The Life Cycle of Resistance to Change

- Leading and managing change:Describing the Core Ideology, Commitment Planning

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Measurement

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Research Design

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Group Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Leadership and Authority, Group Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Third-Party Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Building, Team Building Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Management Styles

- Organization Process Approaches:Application Stages, Microcosm Groups

- Restructuring Organizations:Structural Design, Process-Based Structures

- Restructuring Organizations:Downsizing, Application Stages, Reengineering

- Employee Involvement:Parallel Structures, Multiple-level committees

- Employee Involvement:Quality Circles, Total Quality Management

- Work Design:The Engineering Approach, Individual Differences, Vertical Loading

- Performance Management:Goal Setting, Management by Objectives, Criticism of MBO

- Developing and Assisting Members:Career Stages, Career Planning, Job Pathing

- Developing and Assisting Members:Culture and Values, Employee Assistance Programs

- Organization and Environment Relationships:Environmental Dimensions, Administrative Responses

- Organization Transformation:Sharing the Vision, Three kinds of Interventions

- The Behavioral Approach:The Deep Assumptions Approach

- Seven Practices of Successful Organizations:Training, Sharing Information