|

Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs |

| << Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis |

| Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits >> |

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

18

Diagnosing

Groups and Jobs

Diagnosis

is the second major phase in the model of planned

change. Based on open-systems

theory, a

comprehensive

diagnostic framework for organization-, group-,

and job-level systems was

discussed. The

organization-level

diagnostic model was elaborated

and applied. After the organization level, the

next two

levels

of diagnosis are the group

and job. Many large

organizations have groups or

departments that are

themselves

relatively large. Diagnosis of large

groups can follow the

dimensions and relational

fits

applicable

to organization-level diagnosis. In essence,

large groups or departments

operate much like

organizations,

and their functioning can be

assessed by diagnosing them as

organizations.

Small

departments and groups, however,

can behave differently from

large organizations and so they

need

their

own diagnostic models to reflect

those differences. In the first

section, we discuss the diagnosis

of

work

groups. Such groups

generally consist of a relatively small

number of people working face-to-face

on

a

shared task. Work groups

are prevalent in all sizes of

organizations. They can he relatively

permanent and

perform

an ongoing function, or they can be

temporary and exist only to

perform a certain task or to

make

a

specific decision.

Finally,

we describe and apply a diagnostic model

of individual jobs--the smallest

unit of analysis in

organizations.

An individual job is constructed to

perform a specific task or

set of tasks. How jobs

are

designed

can affect individual and organizational

effectiveness.

Group-Level

Diagnosis:

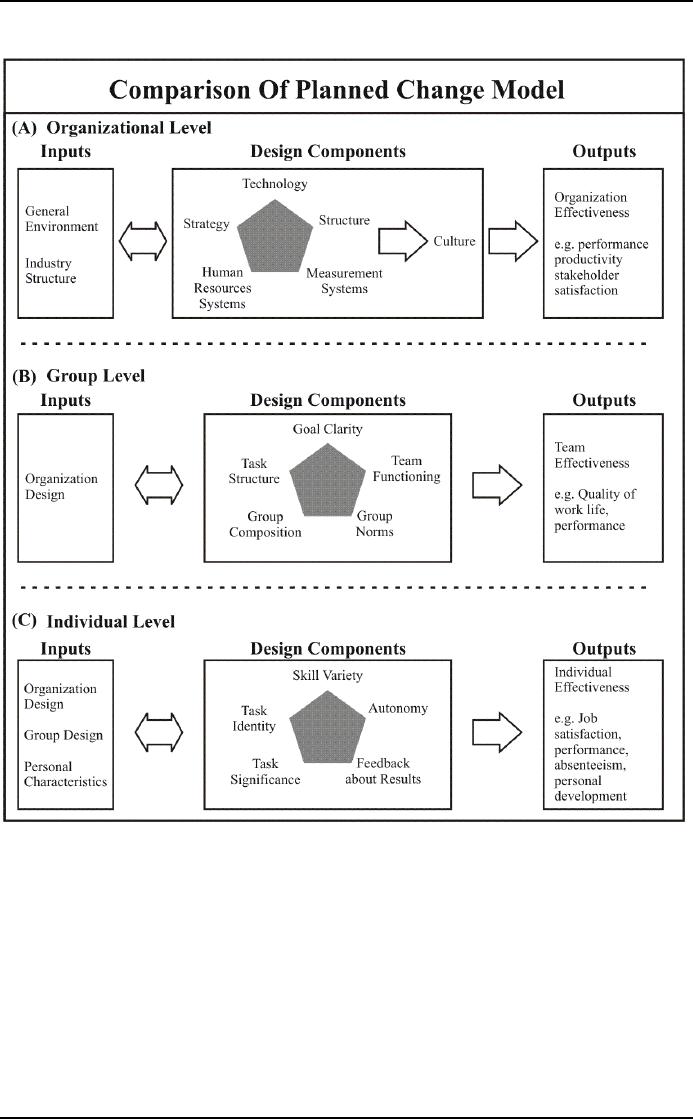

Figure

24 replicates the comprehensive model

discussed earlier but

highlights the group- and

individual-

level

models. It shows the inputs, design

components, outputs, and relational fits

for group-level diagnosis.

The

model is similar to other popular

group-level diagnostic models,

such as Hackman and Morris's

task

group

design model, McCaskey's framework for

analyzing groups, and

Ledford, Lawler, and

Mohrman's

participation

group design model.

Inputs:

Organization

design is clearly the major input to

group design. It consists of the

design components

characterizing

the larger organization within which the

group is embedded: technology,

structure,

measurement

systems, and human resources

systems, as well as organization culture.

Technology can

determine

the characteristics of the group's task;

structural systems can

specify the level of coordination

required

among groups. The human

resources and measurement

systems, such as performance

appraisal

and

reward systems, play an important

role in determining team functioning.

For example,

individually

based

performance appraisal and

reward systems tend to

interfere with team

functioning because

members

may

be more concerned with maximizing

their individual performance to the

detriment of team

performance.

Collecting information about the group's

organization design context can

greatly improve the

accuracy

of diagnosis.

Design

Components:

Figure

24 (B) shows that groups

have five major components:

goal clarity, task

structure, group

composition,

group functioning, and

performance norms.

Goal

clarity involves how well the

group understands its

objectives. In general, goals should be

moderately

challenging;

there should be a method for

measuring, monitoring, and feeding

back information about

goal

achievement;

and the goals should be clearly

understood by all members.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Figure

24: Comprehensive Model for

Diagnosing Organizational

Systems

Task

structure is concerned with

how the group's work is

designed. Task structures

can vary along two

key

dimensions;

coordination of members' efforts

and regulation of their task

behaviors. The

coordination

dimension

involves the degree to which

group tasks are structured

to promote effective interaction

among

group

members. Coordination is important in

groups performing interdependence

tasks, such as

surgical

teams

and problem-solving groups. It is

relatively unimportant, however, in groups

composed of members

who

perform independent tasks, such as a

group of telephone operators or

salespeople. The regulation

dimension

involves the degree to which members

can control their own

task behaviors and be

relatively

free

from external controls such as

supervision, plans, and

programs. Self-regulation generally

occurs when

members

can decide on such issues as

task assignments, work

methods, production goals,

and membership.

Composition

concerns the membership of groups.

Members can differ on a number of

dimensions having

relevance

to group behavior. Demographic variables,

such as age, education,

experience, and skills

and

abilities,

can affect how people behave

and relate to each other in

groups. Demographics can

determine

whether

the group is composed of people having

task-relevant skills and knowledge,

including

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

interpersonal

skills. People's internal

needs also can influence

group behaviors. Individual

differences in

social

needs can determine whether

group membership is likely to be

satisfying or stressful.

Group

functioning is the underlying basis of

group life. How members

relate to each other is

important in

work

groups because the quality of

relationships can affect task

performance. In some groups,

for example

interpersonal

competition and conflict

among members result in

their providing little

support and help

for

each

other. Conversely groups may

become too concerned about

sharing good feelings and

support and

spend

too little time on task

performance. In organization development considerable

effort has been

invested

to help work group members

develop healthy interpersonal relations, including

ability and a

willingness

to share feelings and

perceptions about members' behaviors so

that inter-personal problems

and

task difficulties can he

worked through and resolved.

Group functioning therefore involves

task-related

activities,

such as giving and seeking

information and elaborating,

coordinating, and evaluating

activities;

and

the group-maintenance function, which is

directed toward holding the

group together as a cohesive

team

and includes encouraging, harmonizing,

compromising, setting standards, and

observing.

Performance

norms are member beliefs

about how the group should perform

its task and include

acceptable

levels of performance. Norms derive

from interactions among members

and serve as guides

to

group

behavior. Once members agree

on performance norms, either implicitly

or explicitly, then

members

routinely

perform tasks according to

those norms. For example,

members of problem-solving groups

often

decide

early in the life of the group

that decisions will be made

through voting; voting then

becomes a

routine

part of group task

behavior.

Outputs:

Group

effectiveness has two

dimensions: performance and

quality of work life.

Performance is measured in

terms

of the group's ability to control or

reduce costs, increase

productivity, or improve quality.

This is a

"hard"

measure of effectiveness. In addition,

effectiveness is indicated by the group

member's quality of

work

life. It concerns work

satisfaction, team cohesion,

and organizational commitment.

Fits:

The

diagnostic model in Figure 24(B) shows

that group design components

must fit inputs if groups

are to

be

effective in terms of performance and the

quality of work life.

Research suggests the following

fits

between

the inputs and design

dimensions:

1.

Group

design should be congruent with the

larger organization design. Organization

structures

with

low differentiation and high

integration should have work

groups that are composed of

highly

skilled

and experienced members

performing highly interdependent tasks.

Organizations with

differentiated

structures and formalized human

resources and information

systems should spawn

groups

that have clear,

quantitative goals and

support standardized behaviors.

Although there is

little

direct research on these fits, the

underlying rationale is that congruence

between organization

and

group designs support

overall integration within the

company. When group designs

are not

compatible

with organization designs, groups

often conflict with the organization.

They may

develop

norms that run counter to organizational

effectiveness, such as occurs in

groups

supportive

of horseplay, goldbricking, and

other counterproductive

behaviors.

2.

When

the organization's technology results in interdependent

tasks, coordination among

members

should

be promoted by task structures,

composition, performance norms, and

group functioning.

Conversely

when technology permits independent

tasks, the design components should

promote

individual

task performance. For

example, when coordination is

needed, task structure

might

physically

locate related tasks together;

composition might include members with

similar

interpersonal

skills and social needs;

performance norms would

support task-relevant

interactions;

and

healthy interpersonal relationships would be

developed.

3.

When

the technology is relatively uncertain and requires

high amounts of information

processing

and

decision making, group task

structure, composition, performance

norms, and group

functioning

should promote self-regulation. Members should

have the necessary freedom,

information,

and skills to assign members

to tasks, to decide on production

methods, and to set

performance

goals. When technology is relatively

certain, group designs should

promote

standardization

of behavior, and groups should be

externally controlled by supervisors,

schedules,

and

plans. For example, when self-regulation

is needed, task structure

might be relatively flexible

and

allow the interchange of members

across group tasks;

composition might include

members

with

multiple skills, interpersonal

competencies, and social

needs; performance norms

would

support

complex problem solving; and efforts

would be made to develop healthy

interpersonal

relations.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Application

3: Top-Management Team at Ortiv Glass

Corporation

The

Ortiv Glass Corporation

produces and markets plate

glass for use primarily in

the construction and

automotive

indulines. The multiplant company

has been involved in OD for

several years and

actively

supports

participative management practices and

employee involvement programs.

Ortiv's organization

design

is relatively organic, and the manufacturing

plants are given freedom and

encouragement to develop

their

own organization designs and

approaches to participative management. It

recently put together a

problem-solving

group made up of the top-management

team at its newest

plant.

The

team consisted of the plant

manager and the managers of the

five functional departments

reporting to

him:

engineering (maintenance), administration,

human resources, production,

and quality control.

In

recruiting

managers for the new plant,

the company selected people with

good technical skills

and

experience

in their respective functions. It also

chose people with some

managerial experience and a

desire

to

solve problems collaboratively, a

hallmark of participative management. The

team was relatively new,

and

members had been working

together for only about five

months.

The

team met formally for

two hours each week to

share pertinent information

and to deal with plant

wide

issues

affecting all of the departments, such as

safety procedures, interdepartmental

relations, and

personnel

practices.

Members described these

meetings as informative but

often chaotic in terms of

decision making.

The

meetings typically started

late as members straggled in at

different times. The

latecomers generally

offered

excuses about more pressing

problems occurring elsewhere in the

plant. Once started, the

meetings

were

often interrupted by "urgent"

phone messages for various

members, including the plant

manager, and

in

most cases the recipient would

leave the meeting hurriedly to

respond to the call.

The

group had problems arriving

at clear decisions on particular issues.

Discussions often rambled

from

topic

to topic, and members tended

to postpone the resolution of problems to

future meetings. This led

to

a

backlog of unresolved issues,

and meetings often lasted

far beyond the two-hour limit.

When group

decisions

were made, members often

reported problems in their implementation.

Members typically

failed

to

follow thorough on agreements,

and there was often

confusion about what had actually

been agreed

upon.

Everyone expressed dissatisfaction with

the team meetings and their

results.

Relationships

among team members were

cordial yet somewhat strained,

especially when the team

was

dealing

with complex issues in which

members had varying opinions

and interests. Although the

plant

manager

publicly stated that he

wanted to hear all sides of

the issues, he often interrupted the

discussion or

attempted

to change the topic when members

openly disagreed in their

views of the problem. This

interruption

was typically followed by an

awkward silence in the group. In many

instances when a solution

to

a pressing problem did not

appear forthcoming, members either moved

on to another issue or they

informally

voted on proposed options, letting

majority rule decide the outcome.

Members rarely

discussed

the

need to move on or vote; rather, these

behaviors emerged informally

over time and became

acceptable

ways

of dealing with difficult

issues.

Analysis:

Application

3 presents an example of applying

group-level diagnosis to a top-management

team engaged in

problem

solving.

The

group is having a series of ineffective

problem-solving meetings. Members

report a backlog of

unresolved

issues, poor use of meeting

time, lack of follow through

and decision implementation, and

a

general

dissatisfaction with the team

meeting. Examining group

inputs and design components

and how

the

two fit can help explain the

causes of those group

problems.

The

key issue in diagnosing

group inputs is the design of the

larger organization within which the

group is

embedded.

The Ortiv Glass

Corporation's design is relatively

differentiated. Each plant is allowed to

set up

its

own organization design. Similarly,

although no specific data

are given, the company's

technology,

structure,

measurement systems, human

resources systems, and culture

appear to promote flexible

and

innovative

behaviors at the plant level. Indeed,

freedom to innovate in the manufacturing plants is

probably

an

outgrowth of the firm's OD activities and

participative culture.

In

the case of decision-making groups

such as this one, organization design

also affects the nature of

the

issues

that are worked on.

The team meetings appear to

be devoted to problems affecting all of

the

functional

departments. This suggests

that the problems entail high

interdependence among the

functions;

consequently

high coordination among

members is needed to resolve

them. The team meetings

also seem

to

include many issues that are

complex and not easily

solved, so there is probably a relatively

high amount

of

uncertainty in the technology or work process.

The causes of the problems or

acceptable solutions are

not

readily available. Members must

process considerable information

during problem solving,

especially

when

there are different

perceptions and opinions

about the issues.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Diagnosis

of the team's design components

answers the following

questions:

1.

How

clear are the group's

goals? The

team's goals seem relatively

clear: they are to

solve

problems.

There appears to be no clear agreement,

however on the specific problems to be

addressed. As a

result,

members come late because

they have "more

pressing"

problems needing

attention.

2.

What

is the group's task structure?

The

team's task structure

includes face-to-face

interaction

during the weekly meetings.

That structure allows

members from

different

functional

departments to come together physically

to share information and to

solve

problems

mutually affecting them. It facilitates

coordination of problem solving

among the

departments

in the plant. The structure

also seems to provide team

members with the freedom necessary

to

regulate

their task behaviors in the

meetings. They can adjust

their behaviors and interactions to

suit the

flow

of the discussion and problem-solving

process.

3.

What

is the composition of the group?

The

team is composed of the plant

manager and

managers

of five functional departments.

All members appear to have

task-relevant skills and

experience,

both

in their respective functions

and in their managerial

roles. They also seem to be

interested in solving

problems

collaboratively. That shared

interest suggests that

members have job-related social

needs and

should

feel relatively comfortable in group problem-solving

situations.

4.

What

are the group's performance

norms? Group

norms cannot be observed directly

but must

be

inferred from group

behaviors. The norms involve

member beliefs about how

the group should

perform

its task, including

acceptable levels of performance. A

useful way to describe norms

is to list

specific

behaviors that complete the

sentences "A good group

member should...." and "its

okay to...."

Examination

of the team's problem-solving behaviors

suggests the following performance

norms are

operating

in the example:

·

"It's

okay to come late to team

meetings."

·

"It's

okay to interrupt meetings with

phone messages."

·

"It's

okay to leave meetings to respond to

phone messages."

·

"It's

okay to hold meetings longer than

two hours."

·

"A

good group member should not

openly disagree with others'

views."

·

"It's

okay to vote on

decisions."

·

"A

good group member should be cordial to

other members."

·

"It's

okay to postpone solutions to immediate

problems."

·

"It's

okay not to follow through on previous

agreements."

5.

What

is the nature of team

functioning in the group?

The

case strongly suggests

that

interpersonal

relations are not healthy on the

management team. Members do

not seem to

confront

differences openly. Indeed, the

plant manager purposely intervenes when

conflicts

emerge.

Members feel dissatisfied with the

meetings, but they spend

little time talking about

those

feelings.

Relationships are strained,

but members fail to examine

the underlying causes.

The

problems facing the team can

now be explained by assessing how

well the group design fits

the inputs.

The

larger organization design of Ortiv is

relatively differentiated and promotes

flexibility and innovation

in

its

manufacturing plants. The firm

supports participative management, and

the team meetings can be

seen

as

an attempt to implement that approach at the

new plant. Although it is

too early to tell whether the

team

will

succeed, there does not

appear to be significant incongruity

between the larger organization design

and

what

the team is trying to do. Of

course, team problem solving

may continue to be ineffective,

and the

team

might revert to a more autocratic

approach to decision making. In

such a case, a serious

mismatch

between

the plant management team

and the larger company would

exist, and conflict between

the two

would

likely result.

The

team's issues are highly

interdependent and often uncertain, and

meetings are intended to resolve

plant

wide

problems affecting the various functional

departments. Those problems

are generally complex

and

require

the members to process a great

deal of information and

create innovative solutions. The

team's task

structure

and composition appear to be the nature

of team issues. The

face-to-face meetings help

to

coordinate

problem solving among the department

managers, and except for the

interpersonal skills,

members

seem to have the necessary

task-relevant skills and

experience to drive the

problem-solving

process.

There appears, however, to be a conflict in the

priority between the problems to be

solved by the

team

and the problems faced by

individual managers.

More

important, the key difficulty

seems to be a mismatch between the

team's performance norms

and

interpersonal

relations and the demands of the

problem-solving task. Complex, interdependent

problems

require

performance norms that

support sharing of diverse

and often conflicting kinds of

information. The

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

norms

must encourage members to

generate novel solutions and to

assess the relevance of

problem-solving

strategies

in light of new issues.

Members need to address

explicitly how they are

using their knowledge

and

skills

and how they are weighing

and combining members'

individual contributions.

In

our example, the team's

performance norms fail to support complex

problem solving; rather, they

promote

a problem-solving method that is

often superficial, haphazard,

and subject to external

disruptions.

Members'

interpersonal relationships reinforce adherence to the

ineffective norms. Members do

not

confront

personal differences or dissatisfactions

with the group process. They

fail to examine the very

norms

contributing to their problems. In this

case, diagnosis suggests the

need for group

interventions

aimed

at improving performance norms

and developing healthy interpersonal

relations.

Table of Contents:

- The Challenge for Organizations:The Growth and Relevance of OD

- OD: A Unique Change Strategy:OD consultants utilize a behavioral science base

- What an “ideal” effective, healthy organization would look like?:

- The Evolution of OD:Laboratory Training, Likert Scale, Scoring and analysis,

- The Evolution of OD:Participative Management, Quality of Work Life, Strategic Change

- The Organization Culture:Adjustment to Cultural Norms, Psychological Contracts

- The Nature of Planned Change:Lewin’s Change Model, Case Example: British Airways

- Action Research Model:Termination of the OD Effort, Phases not Steps

- General Model of Planned Change:Entering and Contracting, Magnitude of Change

- The Organization Development Practitioner:External and Internal Practitioners

- Creating a Climate for Change:The Stabilizer Style, The Analyzer Style

- OD Practitioner Skills and Activities:Consultant’s Abilities, Marginality

- Professional Values:Professional Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, Technical Ineptness

- Entering and Contracting:Clarifying the Organizational Issue, Selecting an OD Practitioner

- Diagnosing Organizations:The Process, The Performance Gap, The Interview Data

- Organization as Open Systems:Equifinality, Diagnosing Organizational Systems

- Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Methods for Collecting Data, Observations

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Sampling, The Analysis of Data

- Designing Interventions:Readiness for Change, Techno-structural Interventions

- Leading and Managing Change:Motivating Change, The Life Cycle of Resistance to Change

- Leading and managing change:Describing the Core Ideology, Commitment Planning

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Measurement

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Research Design

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Group Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Leadership and Authority, Group Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Third-Party Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Building, Team Building Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Management Styles

- Organization Process Approaches:Application Stages, Microcosm Groups

- Restructuring Organizations:Structural Design, Process-Based Structures

- Restructuring Organizations:Downsizing, Application Stages, Reengineering

- Employee Involvement:Parallel Structures, Multiple-level committees

- Employee Involvement:Quality Circles, Total Quality Management

- Work Design:The Engineering Approach, Individual Differences, Vertical Loading

- Performance Management:Goal Setting, Management by Objectives, Criticism of MBO

- Developing and Assisting Members:Career Stages, Career Planning, Job Pathing

- Developing and Assisting Members:Culture and Values, Employee Assistance Programs

- Organization and Environment Relationships:Environmental Dimensions, Administrative Responses

- Organization Transformation:Sharing the Vision, Three kinds of Interventions

- The Behavioral Approach:The Deep Assumptions Approach

- Seven Practices of Successful Organizations:Training, Sharing Information