|

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

15

Diagnosing

Organizations

All

consultants advocate expert diagnosis

and action-taking. Engineers and

behavioral scientists alike have

diagnoses

of organizational conflict and prescription

for solving it. Diagnosis

is

medical jargon for the

gap

between

sickness and health. As biology exploded

in the late 19th century, the human body,

like the

workplace,

was divided into manageable

components, too. Doctors

became the industrial engineers of

the

human

physique. Their claim of

expertise was based on their

ability to factor in every relevant

"variable"

and

thus heal the sick.

It

is no surprise that, applying to

industrial science, diagnosis is

conceived as identifying and

closing gaps

between

how things are and how they

should be, using all the

tools of science and

technology.

Lewin

added a new dimension to this model. He

highlighted processes unseen

through 19th-century

eyes

because

nobody had a conceptual lens

powerful enough.

The

concept he developed goes by the name of

the "task/process"

relationship the

subtle chicken/egg

interplay

between ends and means,

methods and goals. A task is

something concrete, observable,

and thing-

oriented.

It can be converted into criteria,

measurements, targets, and

deadlines.

A task

group dynamics

people

were fond of saying

refers to what is to be done.

Process

refers to how. It reflects

perceptions, attitudes, reasoning.

Process diagnosticians ask,

"Why aren't

we

making progress?" They don't ask

when, where, and how

many but why, how,

and whether.

Task/process

thinking can be likened to the

famous visual paradox of the Old

Woman/Young Woman.

Do

you see a young beauty with

her head turned or an old

woman in profile?

Figure

18: Old woman/young

girl

You

can't see both at once. By

some mental gyration, you

can learn to shift between

them.

Action,

on the other hand, reflects pure

process. We guide it largely on

automatic pilot, fueled by

little

explosions

of energy in the right brain of

creativity, insight, synthesis that

can't be quantified or

specified

as "targets."

Through

trained observation, you can diagnose

ingenious linkages between task

and process. When

work

stops,

for example, determine what is

not being talked about the gap

between word and deed, the

all-too-

human

shortfall between aspiration and action.

You must shift attention the

way a pilot scans

instruments

from

compass to altimeter to air speed

indicator to keep task

and process synchronized.

That requires

skills

few of us learn in school.

Unfortunately,

left-brain diagnostic thinking

perfected by scientists for

more than 100 years

leads

people

to pay attention to the compass

and to consider the altimeter a frill.

The diagnoser is assumed

to

stand

outside, impartial, "objective," and

aloof from what is observed. If

you add to this your propensity

to

defer

to authority parents, boss,

and experts you have a

setup for disappointment. For

the

authority/dependency

relationship itself becomes a "process"

issue, especially when the

person invested

with

abilities lacks satisfactory

"answers."

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Group

dynamics' great contribution to

management was its

relentless gaze at the process as

inseparable

from

the task, the diagnoser inseparable

from the diagnosis, a leader's

effectiveness inseparable

from

follower

contributions.

What

is Diagnosis?

Diagnosis

is the process of understanding how the

organization is currently functioning, and it provides

the

information

necessary to design change

interventions. It generally follows

from successful entry

and

contracting,

which set the stage for

successful diagnosis. They

help OD practitioners and client

members

jointly

determine organizational issues to focus

on, how to collect and

analyze data to understand

them,

and

how to work together to develop action

steps from the

diagnosis.

Unfortunately,

the term diagnosis can be misleading when

applied to organizations. It suggests a model

of

organization

change analogous to medicine: an

organization (patient) experiencing problems

seeks help

from

an OD practitioner (doctor); the practitioner

examines the organization, finds the

causes of the

problems,

and prescribes a solution.

Diagnosis in organization development, however, is

much more

collaborative

than such a medical

perspective implies and does

not accept the implicit

assumption that

something

is wrong with the organization.

First,

the values and ethical

beliefs that underlie OD suggest

that both organization members

and change

agents

should be involved in discovering the

determinants of current organizational effectiveness.

Similarly,

both

should be involved actively in developing appropriate

interventions and implementing them.

For

example,

a manager might seek OD help

to reduce absenteeism in his or

her department. The manager

and

an

OD consultant jointly might decide to

diagnose the cause of the problem by

examining company

absenteeism

records and by interviewing

selected employees about possible

reasons for

absenteeism.

Alternatively,

they might examine employee

loyalty and discover the organizational

elements that

encourage

people

to stay. Analysis of those

data could uncover determinants of

absenteeism or loyalty in the

department,

thus helping the manager and

the practitioner to develop an appropriate

intervention to

address

the issue. The choice about

how to approach the issue of

absenteeism and the decisions about

how

to

address it are made jointly

by the OD practitioner and the

manager.

Second,

the medical model of diagnosis also

implies that something is

wrong with the patient and

that one

needs

to uncover the cause of the illness. In

those cases where

organizations do have specific

problems,

diagnosis

can be problem oriented, seeking

reasons for the problems. On the

other hand, as suggested

by

the

absenteeism example above, the

practitioner and the client

may choose to frame the

issue positively.

Additionally,

the client and OD practitioner

may be looking for ways to

enhance the organization's existing

functioning.

Many managers involved with

OD are not experiencing

specific organizational problems.

Here,

diagnosis is development oriented. It assesses the

current functioning of the organization to

discover

areas

for future development. For

example, a manager might be

interested in using OD to improve

a

department

that already seems to be

functioning well. Diagnosis might include

an overall assessment of

both

the task-performance capabilities of the department

and the impact of the department on

its

individual

members. This process seeks

to uncover specific areas for

future development of the

department's

effectiveness.

In

organization development, diagnosis is used

more broadly than a medical

definition would suggest. It

is

a

collaborative process between organization

members and the OD consultant to collect

pertinent

information,

analyze it, and draw

conclusions for action planning

and intervention. Diagnosis

may be aimed

at

uncovering the causes of specific

problems; be focused on understanding

effective processes; or be

directed

at assessing the overall functioning of

the organization or department to discover areas

for future

development.

Diagnosis provides a systematic understanding of

organizations so that appropriate

interventions

may be developed for solving problems

and enhancing

effectiveness.

Organizational

diagnosis is a major practitioner skill.

It usually examines two broad

areas.

The

first area comprises

the various interacting sub-elements that

make up the organization. These

include

the

divisions, departments, products, and the

relationships between them. The

diagnosis may also include

a

comparison

of the top middle, and lower

levels of management in the

organization.

The

second area of

diagnosis concerns the organizational

processes. These include

communication

networks,

team problem-solving, decision-making,

leadership and authority

styles, goal-setting and

planning

methods,

and the management of conflict

and competition.

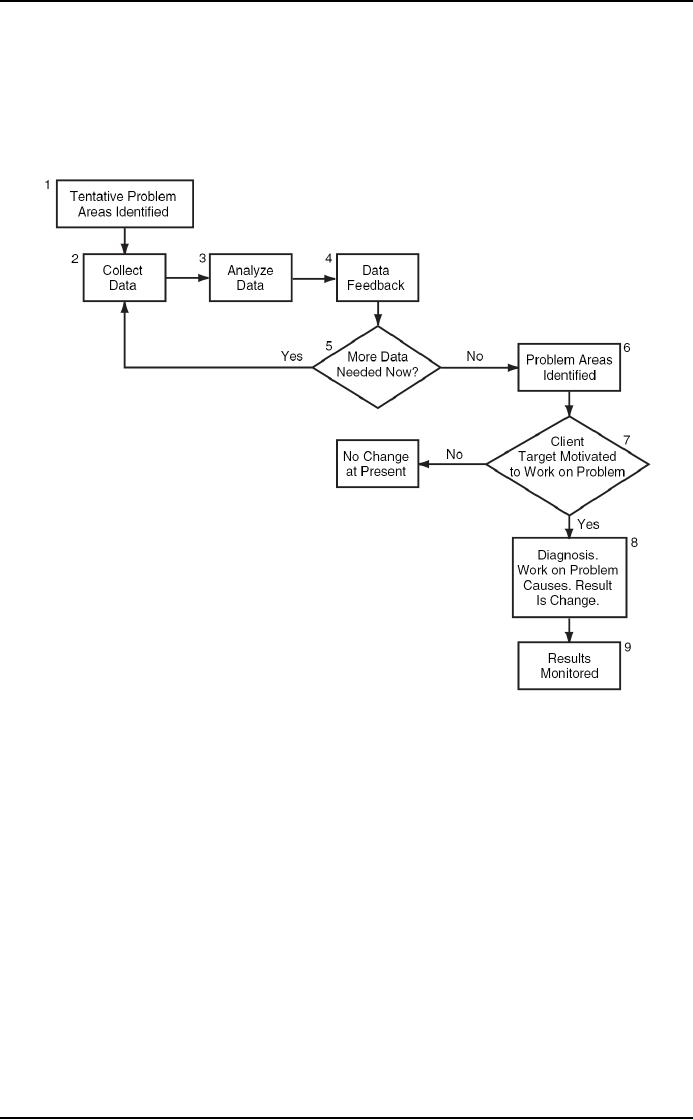

The

Process:

Diagnosis

is a cyclical process that

involves data gathering, interpretations,

and identification of

problem

areas

and possible action programs, as

shown in Figure 19. The

first step is the preliminary

identification of

possible

problem areas. These

preliminary attempts often

bring out symptoms as well

as possible problem

areas.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

The

second step involves gathering

data based on the preliminary

problem identified in the preceding

step.

These

data are categorized,

analyzed and presented to the

client in a feedback session

(steps 3 and 4). If it

is

determined

that enough data are

available (step 5), the

client and practitioner

jointly diagnose and

identify

likely

problem areas (step 6). At

this point, the client's level of

motivation to work on the problems

is

determined

(step 7). Based upon the

diagnosis, the target systems

are identified and the

change strategy is

designed

(step 8). Finally (step

9), the results are

monitored to determine the degree of

change that has

been

attained versus the desired change

goals.

Fig

19: The Diagnostic

Process

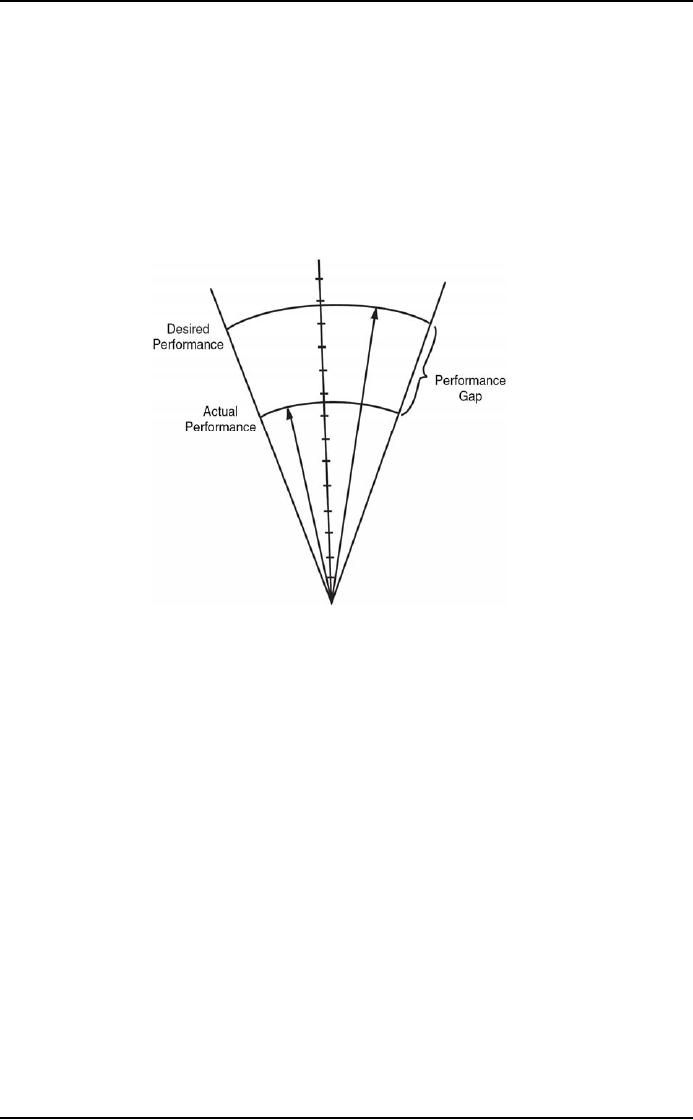

The

Performance Gap:

One

method in the diagnostic process is to

determine the performance

gap---the difference

between

what

the organizations could do by virtue of

its opportunity in its

environment and what it actually

does.

This

leads to an approach that

may be termed gap analysis.

In this method, data are collected on the

actual

state

of the organization on a varying set of dimensions

and also on the ideal or

desired state, that

is,

"where

the organization should be. As shown in Figure

20, the gap, or discrepancy,

between the actual

state

and

the ideal form a basis for

diagnosis and the design of

interventions. The gap may

be the result of

ineffective

performance by internal units or may

emerge because of competitive changes or

new

innovations.

A performance gap may also

occur when the organization fails to

adapt to changes in

its

external

environment.

Competent

organizational diagnosis does not simply

provide information about the system; it

is also helpful

in

designing and introducing action

alternatives for correcting possible

problems. The diagnosis affirms

the

need

for change and the benefits of

possible changes in the client

system. Important problems

are very

often

hidden or obscure, whereas the

more conspicuous and obvious

problems are relatively

unimportant.

In

such situations, dealing

with the obvious may not be

a very effective way to manage change;

this

underscores

the importance of the diagnostic

stage.

A

performance gap may continue

for some time before it is recognized, in

fact, it may never be

recognized.

On

the other hand, the awareness of a

performance gap may unfreeze

the functions within the

organization

that

are most in need of change.

When this happens, conditions

are present for altering the

structure and

function

of the organization by introducing OD

interventions.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

One

OD practitioner suggests a self

assessment version of gap analysis

using questionnaires to

gather

information

in four key areas:

1.

The organization's strengths.

2.

What can be done to take

advantage of the strengths?

3.

The organization's weaknesses.

4.

What can be done to alleviate the

weaknesses?

In

organizational diagnosis, the practitioner is

looking for causality

that is, an implication that

change in

one

factor (such as compensation)

will cause change in another

factor (productivity): a

cause-effect

relationship.

The client is often aware of

the evidence of the problem, such as declining

sales, high

turnover,

or loss of market share the

symptom of a problem. In the diagnosis

phase, the practitioner

tries

to

identify what factors are

causing the problem, and therefore what

needs to be changed to fix

it.

Fig

20: The Performance Gap

The

process of identifying the

organization's strengths

and

weaknesses

often

leads

to

recognition

of performance gaps and to

change programs.

The

Need for Diagnostic

Models:

Entry

and contracting processes can

result in a need to understand a

whole system or some part,

process,

or

feature of the organization. To diagnose an

organization, OD practitioners and organization

members

need

to have an idea about what

information to collect and analyze.

Choices about what to look

for

invariably

depend on how organizations

are perceived. Such

perceptions can vary from

intuitive hunches to

scientific

explanations of how organizations

function. Conceptual frameworks

that people use to

understand

organizations are referred to as

diagnostic models. They

describe the relationships among

different

features of the organization, its context,

and its effectiveness. As a

result, diagnostic models

point

out

what areas to examine and what

questions to ask in assessing

how an organization is

functioning.

However

all models represent simplifications of

reality and therefore choose certain

features as critical.

Focusing

attention on those features,

often to the exclusion of others,

can result in a biased

diagnosis. For

example,

a diagnostic model that relates

team effectiveness to the handling of

interpersonal conflict would

lead

an OD parishioner to ask questions about

relationships among members,

decision-making processes,

and

conflict resolution methods.

Although relevant, those questions ignore

other group issues such as

the

composition

of skills and knowledge, the complexity

of the tasks performed by the group, and

member

inter-dependencies.

Thus, diagnostic models must

be chosen carefully to address the

organization's

presenting

problems as well as to ensure

comprehensiveness.

Potential

diagnostic models are

everywhere. Any collection of

concepts and relationships that

attempts to

represent

a system or explain its

effectiveness can potentially

qualify as a diagnostic model. Major

sources

of

diagnostic models in OD are the

thousands of articles and books

that discuss, describe, and

analyze how

organizations

function. They provide information about

how and why certain

organizational systems,

processes,

or functions are effective. The

studies often concern a

specific facet of organizational

behavior,

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

such

as employee stress, leadership,

motivation, problem solving, group

dynamics, job design, and

career

development

they also can involve the

larger organization and its

con text, including the

environment,

strategy,

structure, and culture. Diagnostic models

can be derived from that

information by noting the

dimensions

or variables that are

associated with organizational

effectiveness.

Another

source of diagnostic models is OD

practitioners' experience in organizations.

That field

knowledge

is a wealth of practical information about

how organizations operate.

Unfortunately only a

small

part

of that vast experience has

been translated into

diagnostic models that

represent the professional

judgments

of people with years of experience in

organizational diagnosis. The models

generally link

diagnosis

with specific organizational processes,

such as group problem solving,

employee motivation, or

communication

between managers and

employees. The models list

specific questions for

diagnosing such

processes.

Let's

look at a general framework for

diagnosing organizations. The

framework describes the

systems

perspective

prevalent in OD today and integrates

several of the more popular

diagnostic models.

The

systems

model provides a useful starting point

for diagnosing organizations or

departments.

Open-Systems

Model:

This

section introduces systems

theory, a set of concepts

and relationships describing the properties

and

behaviors

of things called systems - organizations,

groups, and people, for

example. Systems are viewed

as

unitary

wholes composed of parts or

subsystems; the system serves to

integrate the parts into a

functioning

unit.

For example, organization systems

are composed of departments

such as sales, operations,

and

finance.

The organization serves to coordinate

behaviors of its departments so

that they function together

in

service of a goal or strategy.

The general diagnostic model

based on systems theory that

underlies most

of

OD is called the open -systems

model.

Organization

as Open Systems:

Systems

can vary in how open they are to

their outside environments. Open

systems, such as

organizations

and

people, exchange information

and resources with their

environments. They cannot completely

control

their

own behavior and are

influenced in part by external forces.

Organizations, for example,

are affected

by

such environmental conditions as the

availability of raw material,

customer demands, and

government

regulations.

Understanding how these external forces

affect the organization can help explain

some of its

internal

behavior.

Open

systems display a hierarchical ordering.

Each higher level of system comprises

lower-level systems:

systems

at the level of society comprise

organizations; organizations comprise

groups (departments);

and

groups

comprise individuals. Although

systems at different levels vary in

many ways--in size

and

complexity,

for example--they have a number of common

characteristics by virtue of being open

systems,

and

those properties can be applied to

systems at any level. The

following key properties of open

systems

are

described below: inputs, transformations, and outputs;

boundaries; feedback; equifinality;

and

alignment.

Case:

The Old Family

Bank

The

Old Family Bank is a large bank in a

southeastern city. As a part of a

comprehensive internal

management

study, H. Day, the data-processing

vice-president, examined the turnover,

absenteeism, and

productivity

figures of all the bank's

work groups. The results

Day obtained offered no real

surprises except

in

the case of the check-sorting and

data-processing departments.

The

study

The

study revealed that, in general, the

departments displaying high turnover

and absenteeism rates had

low

production

figures, and those with

low turnover and absenteeism

were highly productive. When

the check-

sorting

and data-processing figures

were analyzed, Day

discovered that two

departments were tied for

the

lead

for the lowest turnover and

absenteeism figures. What

was surprising was the

check-sorting

department

ranked first as the most

productive unit, whereas the electronic

data-processing department

ranked

last.

This

inconsistency was further

complicated by the fact that the

working conditions for

check-sorting

employees

are very undesirable. They work in a

large open room that is hot

in the summer and cold in

the

winter.

They work alone and operate

high-speed check-sorting machines

requesting a high degree

of

accuracy

and concentration. There is little chance

for interaction because they

take rotating coffee

breaks.

The

computer room is air-conditioned, with a

stable temperature year around: it

has perfect lighting and

is

quiet

and comfortable. Both groups

are known to be highly

cohesive, and the workers in

each department

function

well with one another. This

observation was reinforced by the study's

finding of the low levels

of

turnover

and absenteeism.

The

Interview Data

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

In

an effort to understand this phenomenon,

Day decided to interview the

members of both

departments

in

order to gain some insight

into the dynamics of each group's

behavior. Day discovered

that the check-

sorting

department displayed a great deal of

loyalty to the company. Most of the

group members are

unskilled

or semiskilled workers; although they

have no organized union, they

all felt that the company

had

made

special efforts to keep

their wages and benefits in

line with unionized

operations. They knew that

their

work required team effort

and were committed to high

performance.

A

quite different situation

existed in the data-processing

department. Although the workers

liked their

fellow

employees, there was a

uniform feeling among this highly skilled

group that management put

more

emphasis

on production than on staff units. They

felt that the operating departments

had gotten better pay

raises,

and that the wag gap

did not reflect the skill

differences between employees. As a

result, a large

percentage

of the group's members displayed little

loyalty to the company, even

though they were very

close

to one another.

Case

Analysis Form

Name:

____________________________________________

I.

Problems

A.

Macro

1.

____________________________________________________

2.

____________________________________________________

B.

Micro

1.

_____________________________________________________

2.

_____________________________________________________

II.

Causes

1.

_____________________________________________________

2.

_____________________________________________________

3.

_____________________________________________________

III.

Systems affected

1.

Structural

____________________________________________

2.

Psychosocial

__________________________________________.

3.

Technical

______________________________________________

4.

Managerial

_____________________________________________

5.

Goals

and values

__________________________________________

IV.

Alternatives

1.

_________________________________________________________

2.

_________________________________________________________

3.

________________________________________________________

V.

Recommendations

1.

_________________________________________________________

2.

__________________________________________________________

3.

__________________________________________________________

Case

Solution: The Old Family

Bank

I.

Problems

A.

Macro

1.

The

lack of loyalty to the entire bank could

affect the effectiveness (and

profitability) of the bank.

2.

The

bank may have a poor process

for setting pay

policies.

B.

Micro

1.

Though

the personnel in the data-processing department

have a strong team, they are

not

loyal

to the larger organization.

2.

Data-processing

personnel believe that

management does not

appreciate them, their

skills, and

contributions.

3.

Data-processing

personnel may be underpaid when compared

to similar workers in

other

companies.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

II.

Causes

1.

The

skilled workers in the data-processing department do

not recognize all of the

factors that may

affect

pay and rewards.

2.

The

data-processing personnel possibly

has access to more

company-wide information by

virtue

of

the type of work their department does

than do personnel in other

departments. Consequently, they

get

a

portion of the data without understanding

how managers make

decisions based upon

that data.

III.

Systems affected

The

attitude of the data-processing personnel

to the bank likely affects the entire

bank's

operations.

IV.

Alternatives

1.

H.

Day gathers more data to

confirm/disprove initial

diagnosis.

2.

Use

a diagnosis model such as force-field

analysis to better understand the

problem. Working

through

the model may bring to light

ways to change the situation in the

data-processing

department.

3.

Day

checks on regional employment data to

determine if data-processing personnel

are being paid

competitively

with similar workers in

other companies. Adjust pay

if warranted by the data.

4.

Meet

with the department and explain the

bank's procedures and rationale

for how pay levels

are

set.

V.

Recommendations

All

of the alternatives listed above

can be undertaken by Day.

Table of Contents:

- The Challenge for Organizations:The Growth and Relevance of OD

- OD: A Unique Change Strategy:OD consultants utilize a behavioral science base

- What an “ideal” effective, healthy organization would look like?:

- The Evolution of OD:Laboratory Training, Likert Scale, Scoring and analysis,

- The Evolution of OD:Participative Management, Quality of Work Life, Strategic Change

- The Organization Culture:Adjustment to Cultural Norms, Psychological Contracts

- The Nature of Planned Change:Lewin’s Change Model, Case Example: British Airways

- Action Research Model:Termination of the OD Effort, Phases not Steps

- General Model of Planned Change:Entering and Contracting, Magnitude of Change

- The Organization Development Practitioner:External and Internal Practitioners

- Creating a Climate for Change:The Stabilizer Style, The Analyzer Style

- OD Practitioner Skills and Activities:Consultant’s Abilities, Marginality

- Professional Values:Professional Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, Technical Ineptness

- Entering and Contracting:Clarifying the Organizational Issue, Selecting an OD Practitioner

- Diagnosing Organizations:The Process, The Performance Gap, The Interview Data

- Organization as Open Systems:Equifinality, Diagnosing Organizational Systems

- Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Methods for Collecting Data, Observations

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Sampling, The Analysis of Data

- Designing Interventions:Readiness for Change, Techno-structural Interventions

- Leading and Managing Change:Motivating Change, The Life Cycle of Resistance to Change

- Leading and managing change:Describing the Core Ideology, Commitment Planning

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Measurement

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Research Design

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Group Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Leadership and Authority, Group Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Third-Party Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Building, Team Building Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Management Styles

- Organization Process Approaches:Application Stages, Microcosm Groups

- Restructuring Organizations:Structural Design, Process-Based Structures

- Restructuring Organizations:Downsizing, Application Stages, Reengineering

- Employee Involvement:Parallel Structures, Multiple-level committees

- Employee Involvement:Quality Circles, Total Quality Management

- Work Design:The Engineering Approach, Individual Differences, Vertical Loading

- Performance Management:Goal Setting, Management by Objectives, Criticism of MBO

- Developing and Assisting Members:Career Stages, Career Planning, Job Pathing

- Developing and Assisting Members:Culture and Values, Employee Assistance Programs

- Organization and Environment Relationships:Environmental Dimensions, Administrative Responses

- Organization Transformation:Sharing the Vision, Three kinds of Interventions

- The Behavioral Approach:The Deep Assumptions Approach

- Seven Practices of Successful Organizations:Training, Sharing Information