|

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

13

Professional

Values

Values

have played an important

role in organization development from its

beginning. Traditionally, OD

professionals

have promoted a set of

values under a humanistic framework,

including a concern for

inquiry

and

science, democracy and being

helpful. They have sought to

build trust and collaboration; to

create an

open,

problem-solving climate; and to

increase the self-control of organization

members. More recently,

OD

practitioners have extended those

humanistic values to include a concern

for improving organizational

effectiveness

(for example, to increase

productivity or to reduce turnover)

and performance (for

example,

to

increase profitability). They have

shown an increasing desire to

optimize both human benefits

and

production

objectives.

We

can gain some understanding of the

values represented by OD by referring to

sensitivity training. This

method

of education and change has

a humanistic value orientation, the

belief that it is worthwhile to

have

the

opportunity throughout their

lives to learn and develop

personally toward a full realization

and

actualization

of individual potential.

Another

OD value that came even

more directly from sensitivity

training is that people's

feelings are just as

important

a source of data for

diagnosis and have as much

implication for change as do

facts or so-called

hard

data and people's thoughts

and opinions, and that

these feelings should be considered as

legitimate for

expression

in the organization as any thought, fact,

or opinion.

Yet

another OD value stemming from

sensitivity training is that conflict,

whether interpersonal or inter-

group,

should be brought to the surface and

dealt with directly, rather

than ignored, avoided, or

manipulated.

When

sensitivity training was at the height of

its popularity, two main

value systems considered

were: a

spirit

of inquiry, and

democracy.

The

spirit

of inquiry comes

from the values of science.

Two parts of it are relevant: the

hypothetical spirit

being tentative checking on the validity of

assumptions, and allowing

for errors; and experimentation

putting

ideas or assumptions to the test. In

sensitive training, "all

experienced behavior is subjected

to

questioning

and examination, limited only by the

threshold of tolerance to truth and

new ideas".

The

second main value system,

the democratic

value has

two elements: collaboration,

and conflict

resolution

through rational means. The

learning process in sensitivity training is

collaborative between

participant

and trainer, not a

traditional authoritarian student-teacher

relationship. By conflict

resolution

through

rational means, it is meant

that irrational behavior or

emotion was off limits, but

"that there is a

problem-solving

orientation to conflict rather than the

more traditional approaches

based on bargains,

power

plays, suppression, or

compromise".

More

recently, OD practitioners have extended

those humanistic values to include a

concern for:

improving

organizational effectiveness (for

example, to increase productivity or to

reduce turnover), and

improving

performance (for example, to

increase profitability).

They

have shown an increasing

desire to optimize both

human benefits and production

objectives.

It

is painfully obvious that

most organizations treat their

most valued resources

employees as if they

were

expendable. The all-too-frequent

attitude among managers is,

"If our employees don't like

the jobs we

provide,

they can find employment elsewhere, we

pay them a fair wage and

they receive excellent

fringe

benefits."

In the name of efficiency and economic or

top management pressure,

some people in

organizations

may be bored, some may be

discriminated against, and

many may be treated unfairly

or

inequitably

regarding their talent and

performance. If OD helps correct

these imbalances, it is

long

overdue,

but what about the organization? If it doesn't

survive, there will be no

jobs, no imbalances to

correct.

Of the two words, represented by

OD, Practitioners have spent

more time on development than

on

organization. They are equally important;

however, if either is out of balance, the OD

consultant's goal

is

to redress the imbalance.

OD's

right goal grows from

its proper setting. If the

proper setting is organizations,

then there is only

one

right

goal for OD, i.e. to

confront an issue that is the tension

between freedom and constraint. OD's

right

purpose

is to redress the balance between freedom

and constraint.

There

is always tension between the two

the autonomy of the individual and the

requirements of the

organization.

It is practically impossible to determine the

proper balance but, when

either factor is

obviously

out of balance, the OD consultant's

goal is to work toward

reducing the heavier

side.

The

joint values of humanizing organizations

and improving their

effectiveness have received

widespread

support

in the OD profession as well as increasing

encouragement from managers,

employees, and union

officials.

Indeed, it would be difficult

not to support those joint

concerns. But in practice OD

professionals

face

serious challenges in simultaneously

pursuing greater humanism and

organizational effectiveness. More

practitioners

are experiencing situations in

which there is conflict

between employees' needs for

greater

meaning

and the organization's need

for more effective and

efficient use of its

resources. For

example,

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

expensive

capital equipment may run

most efficiently if it is highly

programmed and routinized,

but people

may

not derive satisfaction from

working with such technology. Should

efficiency be maximized at the

expense

of people's satisfaction? Can technology

be changed to make it more humanly

satisfying while

remaining

efficient? What compromises are

possible? How do these tradeoffs

shift when they are applied in

different

social cultures? These are

the value dilemmas often

faced when we try to

optimize both human

benefits

and organizational effectiveness.

In

addition to value issues

within organizations, OD practitioners

are dealing more and

more with value

conflicts

with powerful outside

groups. Organizations are open systems

and exist within

increasingly

turbulent

environments. For example, hospitals

are facing complex and

changing task environments.

This

has

led to a proliferation of external stakeholders

with interests in the organization's

functioning, including

patients,

suppliers, medical groups,

insurance companies, employers, the

government, stockholders, unions,

the

press, and various interest

groups. Those external groups

often have different and

competing values for

judging

the organization's effectiveness. For

example, stockholders may

judge the firm in terms of

earnings

per

share, the government in terms of

compliance with equal employment

opportunity legislation, patients

in

terms of quality of care,

and ecology groups in terms

of hazardous waste disposal.

Because organizations

must

rely on these external groups for

resources and legitimacy, they cannot simply ignore

these competing

values.

They must somehow respond to them

and try to reconcile the

different interests.

Recent

attempts to help firms manage external

relationships suggest the need for

new interventions and

competence

in OD. Practitioners must

have not only social

skills but also political

skills. They must un-

derstand

the distribution of power, conflicts of

interest, and value dilemmas

inherent in managing external

relationships

and be able to manage their

own role and values

with respect to those

dynamics,

Interventions

promoting collaboration and

system maintenance may he

ineffective in this larger

arena,

especially

when there are power and

dominance relationships among

organizations and competition

for

scarce

resources. Under those conditions, OD

practitioners may need more

power-oriented interventions,

such

as bargaining, coalition forming, and

pressure tactics.

For

example, firms in the tobacco industry

have waged an aggressive

campaign against the efforts

of

external

groups, such as the ILS.

Surgeon general, the American Lung

Association, and local

governments,

to

limit or ban the smoking of

tobacco products. They have

formed a powerful industry coalition to

lobby

against

antismoking legislation; they have spent

enormous sums of money advertising

tobacco products,

conducting

public relations campaigns, and

refuting research purportedly showing the

dangers of smoking.

Such

power-oriented strategies are intended to

manage an increasingly hostile

environment and may

be

necessary

for the industry's survival.

People

practicing OD in such settings may

need to help organizations implement

such strategies if

organizations

are to manage their environments

effectively. That effort

will require political skills

and

greater

attention to how the OD practitioner's

own values fit with

those of the organization.

Professional

Ethics:

Ethical

issues in OD are concerned

with how practitioners perform

their helping relationship

with

organization

members. Inherent in any

helping relationship is the potential for

misconduct and client

abuse.

OD practitioners can let personal

values stand in the way of

good practice or use the power

inherent

in

their professional role to

abuse (often unintentionally)

organization members.

Ethical

Guidelines:

To

its credit, the field of OD always

has shown concern for the

ethical conduct of its practitioners.

There

have

been several articles and

symposia about ethics in OD.

In addition, statements of ethics

governing

OD

practice have been sponsored

by the Organization Development Institute, the

American Society for

Training

& Development, and a consortium of

professional associations in OD.

The consortium has

jointly

sponsored

an ethical code derived from a

large-scale project conducted at the

Center for the Study

of

Ethics

in the Professions at the Illinois

Institute of Technology- The

project's purposes included

preparing

critical

incidents describing ethical

dilemmas and using that

material for professional

and continuing

education

in OD, providing an empirical basis

for a statement of values

and ethics for OD

professionals,

and

initiating a process for making the

ethics of OD practice explicit on a

continuing basis. The

ethical

guidelines

from that project appear in

the appendix to this chapter.

Ethical

Dilemmas:

Although

adherence to statements of ethics

helps prevent the occurrence of ethical

problems, OD

practitioners

still can encounter ethical

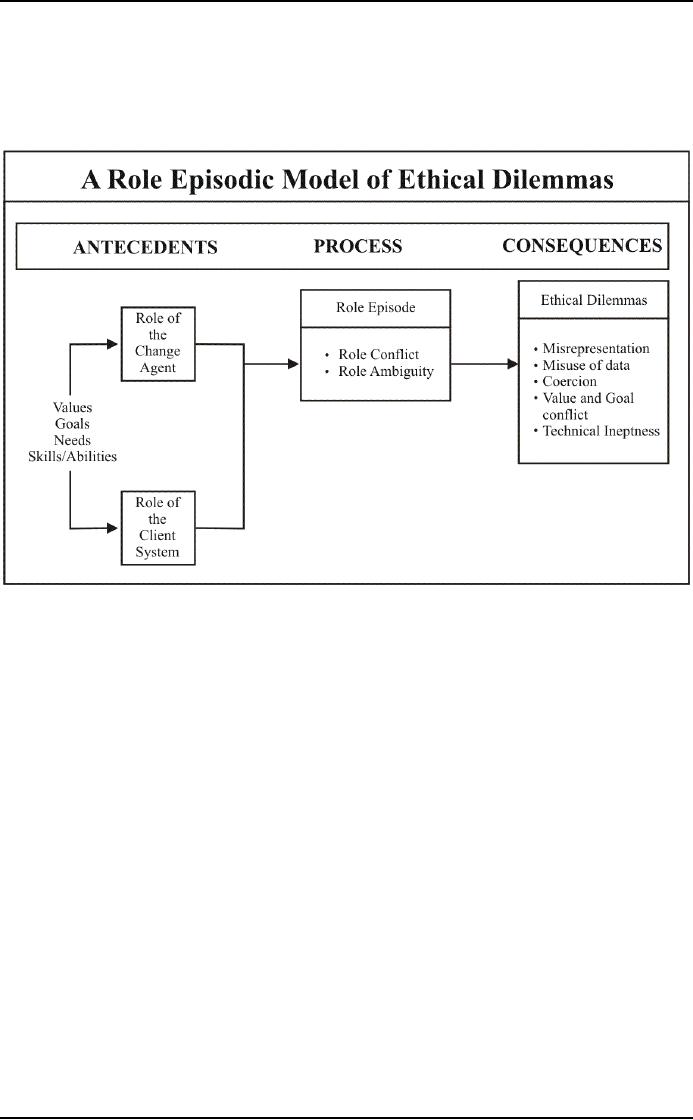

dilemmas. Figure 17 is a process model

that explains how

ethical

dilemmas

can occur in OD. The

antecedent conditions include an OD

practitioner and a client system

with

different

goals, values, needs,

skills, and abilities. During the

entry and contracting phase

these differences

may

or may not be addressed and

clarified. If the contracting process is incomplete, the

subsequent

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

intervention

process or role episode is

subject to role conflict and

role ambiguity. Neither the

client nor the

OD

practitioner is clear about

respective responsibilities. Each party

is pursuing different goals, and

each is

using

different skills and values

to achieve those goals. The

role conflict and ambiguity

may produce five

types

of ethical dilemmas: misrepresentation,

misuse of data, coercion,

value and goal conflict,

and

technical

ineptness.

Figure:

17

Misrepresentation:

Misrepresentation

occurs when OD practitioners claim

that an intervention

will

produce

results that are

unreasonable for the change program or

the situation. The client can

contribute to

the

problem by portraying inaccurate

goals and needs. In either

case, one or both parties

are operating

under

false pretenses and an

ethical dilemma exists. For

example, in an infamous case called

"The

Undercover

Change Agent." an attempt was

made to use laboratory

training in an organization whose

top

management

did not understand it and

was not ready for

it. The OD consultant sold

T-groups as the

intervention

that would solve the

problems facing the organization. After

the president of the firm made

a

surprise

visit to the site where the

training was being held, the consultant

was fired because the nature

and

style

of the T-group was in direct

contradiction to the president's concepts

about leadership.

Misrepresentation

is likely to occur in the entering and

contracting phases of planned change when

the

initial

consulting relationship is being established- To

prevent misrepresentation, OD practitioners

need to

gain

clarity about the goals of the change

effort and to explore openly

with the client its expected

effects, its

relevance

to the client system, and the

practitioner's competence in executing the

intervention.

Misuse

of Data: Misuse

of data occurs when information

gathered during the OD process is

used

punitively.

Large amounts of information

are invariably obtained during the

entry and diagnostic phases

of

OD.

Although most OD practitioners value

openness and trust, it is important

that they be aware of

how

such

data are going to be used. It is a

human tendency to use data

to enhance a power position.

Openness

is

one thing, but leaking

inappropriate information can be

harmful to individuals and to the

organization. It

is

easy for a consultant, under the

guise of obtaining information, to

gather data about whether a

particular

manager

is good or bad. When, how,

or if this information can be used is an

ethical dilemma not

easily

resolved.

To minimize misuse of data, practitioners should

reach agreement up front

with organization

members

about how data collected

during the change process

will be used. This agreement

should be

reviewed

periodically in light of changing

circumstances.

Coercion:

Coercion

occurs when organization members

are forced to participate in an OD

intervention.

People

should have the freedom to choose whether to

participate in a change program if they are to

gain

self-reliance

to solve their own problems.

In team building, for

example, team members should

have the

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

option

of deciding not to become involved in the

intervention. Management should not

decide unilaterally

that

team building is good for

members. However, freedom to make a

choice requires knowledge

about

OD.

Many organization members have

little information about OD

interventions, what they involve,

and

the

nature and consequences of

becoming involved with them.

This makes it imperative for OD

practitioners

to educate clients about interventions

before choices are made for

implementing them.

Coercion

also can pose ethical

dilemmas for the helping relationship

between OD practitioners and

organization

members. Inherent in any

helping relationship are possibilities

for excessive manipulation

and

dependency,

two facets of coercion.

Kelman pointed out that

behavior change "inevitably

involves some

degree

of manipulation and control,

and at least an implicit

imposition of the change agent's

values on the

client

or the person he [or she] is

influencing." This places the

practitioner on two horns of a dilemma:

(1)

any

attempt to change is in itself a change

and thereby a manipulation, no matter

how slight, and (2)

there

exists

no formula or method to structure a

change situation so that

such manipulation can be

totally absent.

To

attack the first aspect of the

dilemma, Kelman stressed freedom of

choice, seeing any action

that limits

freedom

of choice as being ethically ambiguous or

worse. To address the second

aspect, Kelman argued

that

the 00 practitioner must remain keenly

aware of her or his own

value system and alert to

the possibility

that

those values are being

imposed on a client. In other words, an

effective way to resolve this dilemma

is

to

make the change effort as open as

possible, with the free

consent and knowledge of the

individuals

involved.

The

second facet of coercion

that can pose ethical

dilemmas for the helping relationship

involves

dependency.

Helping relationships invariably create

dependency between those who

need help and

those

who

provide it, A major goal in OD is to

lessen clients' dependency on

consultants by helping clients

gain

the

knowledge and skills to address

organizational problems and manage

change themselves. In some

cases,

however,

achieving independence from OD

practitioners can result in clients being

either counter

dependent

or over dependent, especially in the

early stages of the relationship. To

resolve dependency

issues,

consultants can openly and

explicitly discuss with the

client how to handle the

dependency problem,

especially

what the client and consultant expect of

one another. Another

approach is to focus on

problem

finding.

Usually, the client is looking for a

solution to a perceived problem.

The consultant can redirect the

energy

to improved joint diagnosis so

that both are working on

problem identification and

problem

solving.

Such action moves the energy of the

client away from dependency.

Finally, dependency can

be

reduced

by changing the client's expectation from

being helped or controlled by the practitioner to a

greater

focus

on the need to manage the problem. Such a

refocusing can reinforce the

understanding that the

consultant

is working for the client

and offering assistance that

is at the client's discretion.

Value

and Goal Conflict: This

ethical conflict occurs when

the purpose of the change effort is

not clear

or

when the client and the practitioner

disagree over how to achieve

the goals. The important

practical

issue

for OD consultants is whether it is

justifiable to withhold services

unilaterally from an organization

that

does not agree with

their values or methods. OD pioneer

Gordon Lippitt suggested

that the real

question

is the following: assuming that

some kind of change is going to

occur anyway, doesn't the

con-

sultant

have a responsibility to try to guide the

change in the most constructive fashion

possible? That

question

may be of greater importance and

relevance to an internal consultant or to a consultant

who

already

has an ongoing relationship with the

client.

Argyris

takes an even stronger

stand, maintaining that the responsibilities of

professional OD practitioners

to

clients are comparable to

those of lawyers or physicians,

who, in principle, may not

refuse to perform

their

services. He suggests that the very

least the consultant can do is to provide

"first aid" to the

organization,

as long as the assistance does

not compromise the consultant's

values. Argyris suggests

that if

the

Ku Klux Klan asked for

assistance and the consultant could at

least determine whether the KKK

was

genuinely

interested in assessing itself and

willing to commit itself to all

that a valid assessment

would entail

concerning

both itself and other

groups, the consultant should be willing to help. If

later the Klan's

objectives

proved to be less than honestly

stated, the consultant would be free to

withdraw without being

compromised.

Technical

Ineptness: This

final ethical dilemma occurs

when OD practitioners try to implement

inter-

ventions

for which they are not

skilled or when the client attempts a

change for which it is not

ready.

Critical

to the success of any OD program is the

selection of an appropriate intervention,

which depends,

in

turn, on careful diagnosis of the

organization. Selecting an intervention is

closely related to the

practitioner's

own values, skills, and

abilities. In solving organizational problems, many OD

consultants

emphasize

a favorite intervention or technique,

such as team building, total

quality management, or

self-

managed

teams. They let their

own values and beliefs

dictate the change method, Technical

ineptness

dilemmas

also can occur when

interventions do not align with the

ability of the organization to implement

them.

Again, careful diagnosis can

reveal the extent to which the organization is ready

to make a change

and

possesses the skills and knowledge to

implement an ethical dilemma that

arises frequently in OD con-

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

sulting.

What points in the process

represent practical opportunities to

intervene? Do you agree

with

Kindred's

resolution to the problem? What

other options did she

have?

Table of Contents:

- The Challenge for Organizations:The Growth and Relevance of OD

- OD: A Unique Change Strategy:OD consultants utilize a behavioral science base

- What an “ideal” effective, healthy organization would look like?:

- The Evolution of OD:Laboratory Training, Likert Scale, Scoring and analysis,

- The Evolution of OD:Participative Management, Quality of Work Life, Strategic Change

- The Organization Culture:Adjustment to Cultural Norms, Psychological Contracts

- The Nature of Planned Change:Lewin’s Change Model, Case Example: British Airways

- Action Research Model:Termination of the OD Effort, Phases not Steps

- General Model of Planned Change:Entering and Contracting, Magnitude of Change

- The Organization Development Practitioner:External and Internal Practitioners

- Creating a Climate for Change:The Stabilizer Style, The Analyzer Style

- OD Practitioner Skills and Activities:Consultant’s Abilities, Marginality

- Professional Values:Professional Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, Technical Ineptness

- Entering and Contracting:Clarifying the Organizational Issue, Selecting an OD Practitioner

- Diagnosing Organizations:The Process, The Performance Gap, The Interview Data

- Organization as Open Systems:Equifinality, Diagnosing Organizational Systems

- Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Methods for Collecting Data, Observations

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Sampling, The Analysis of Data

- Designing Interventions:Readiness for Change, Techno-structural Interventions

- Leading and Managing Change:Motivating Change, The Life Cycle of Resistance to Change

- Leading and managing change:Describing the Core Ideology, Commitment Planning

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Measurement

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Research Design

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Group Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Leadership and Authority, Group Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Third-Party Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Building, Team Building Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Management Styles

- Organization Process Approaches:Application Stages, Microcosm Groups

- Restructuring Organizations:Structural Design, Process-Based Structures

- Restructuring Organizations:Downsizing, Application Stages, Reengineering

- Employee Involvement:Parallel Structures, Multiple-level committees

- Employee Involvement:Quality Circles, Total Quality Management

- Work Design:The Engineering Approach, Individual Differences, Vertical Loading

- Performance Management:Goal Setting, Management by Objectives, Criticism of MBO

- Developing and Assisting Members:Career Stages, Career Planning, Job Pathing

- Developing and Assisting Members:Culture and Values, Employee Assistance Programs

- Organization and Environment Relationships:Environmental Dimensions, Administrative Responses

- Organization Transformation:Sharing the Vision, Three kinds of Interventions

- The Behavioral Approach:The Deep Assumptions Approach

- Seven Practices of Successful Organizations:Training, Sharing Information