|

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

Lesson

10

The

Organization Development

Practitioner:

A

closer look at OD practitioners can

provide a more personal

perspective on the field and

can help us

understand

the essential character of OD as a

helping profession, involving

personal relationships between

practitioners

and organization members.

Much

of the literature about OD practitioners views them as

internal or external consultants

providing

professional

services--diagnosing problems, developing solutions,

and helping to implement them.

More

recent

perspectives expand the practice

scope to include professionals in related

disciplines, such as

industrial

psychology and organization theory, as

well as line managers who

have learned how to carry

out

OD

to change and develop their

departments.

A

great deal of opinion and

some research studies have

focused on the necessary skills

and knowledge of

an

effective OD practitioner. Studies of the

profession provide a comprehensive

list of basic skills

and

knowledge

that all effective OD practitioners must

possess.

Most

of the relevant literature focuses on people

specializing in OD as a profession and

addresses their

roles

and careers. The OD role

can be described in relation to the

position of practitioners: internal to

the

organization,

external to it, or in a team comprising

both internal and external

consultants. The OD

role

also

can be examined in terms of

its marginality in organizations, of the

emotional demands made on

the

practitioner,

and of where it fits along a

continuum from client-centered to

consultant-centered

functioning.

Finally, organization development is an emerging

profession providing alternative

opportunities

for gaining competence and developing a

career. The stressful nature

of helping professions,

however,

suggests that OD practitioners must

cope with the possibility of

professional burnout.

As

in other helping professions,

such as medicine and law,

values and ethics play an

important role in

guiding

OD practice and in minimizing the

chances that clients will be

neglected or abused.

Who

is the Organization Development

Practitioner?

The

term organization development practitioner refers to

at least three sets of

people. The most

obvious

group

of OD practitioners are those people

specializing in OD as a profession. They

may be internal or

external

consultants who offer

professional services to organization

clients, including top

managers,

functional

department heads, and staff groups. OD

professionals traditionally have

shared a common set of

humanistic

values promoting open communications,

employee involvement, and

personal growth and

development.

They tend to have common

training, skills, and

experience in the social processes

of

organizations

(for example, group

dynamics, decision making,

and communications). In recent

years, OD

professionals

have expanded those

traditional values and skill

sets to include more concern

for

organizational

effectiveness, competitiveness, and

bottom-line results, and

greater attention to the

technical,

structural,

and strategic parts of

organizations. That expansion, mainly in

response to the highly

competitive

demands facing modern organizations, has

resulted in a more diverse

set of OD professionals

geared

to helping organizations cope

with those pressures.

Second:

the term OD

practitioner applies to people

specializing in fields related to OD,

such as reward

systems,

organization design, total quality,

information technology, and business

strategy. These

content-

oriented

fields increasingly are becoming

integrated with OD's process

orientation, particularly as OD

projects

have become more

comprehensive, involving multiple

features and varying parts of

organizations.

For

example is the result of marrying OD with

business strategy. A growing number of

professionals in

these

related fields are gaining experience

and competence in OD, mainly

through working with

OD

professionals

on large-scale projects and

through attending OD training sessions.

For example, most of

the

large

accounting firms have diversified

into management consulting and

change management. In

most

cases,

professionals in these related fields do

not subscribe fully to

traditional OD values, nor do they

have

extensive

OD training and experience.

Rather, they have formal

training and experience in

their respective

specialties,

such as industrial relations,

management consulting, information

systems, health care, and

work

design.

They are OD practitioners in the sense

that they apply their special

competence within an

OD-like

process,

typically by engaging OD professionals

and managers to design and

implement change programs.

They

also practice OD when they apply their OD

competence to their own

specialties, thus spreading

an

OD

perspective into such areas

as compensation practices, work

design, labor relations, and

planning and

strategy.

Third:

the term OD

practitioner applies to the increasing

number of managers and administrators

who

have

gained competence in OD and

who apply it to their own

work areas. Studies and

recent articles argue

that

OD applied by managers rather than OD

professionals is growing rapidly.

They suggest that the

faster

pace

of change affecting organizations today is

highlighting the centrality of the manager in

managing

change.

Consequently, OD must become a

general management skill.

Along those lines, Kanter

studied a

growing

number of firms, such as General Electric, Hewlett-Packard,

and 3M, where managers

and

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

employees

have become "change masters.

They have gained the expertise to

introduce change and

inno-

vation

into the organization.

Managers

tend to gain competence in OD

through interacting with OD professionals

in actual change

programs.

This on-the-job training

frequently is supplemented with

more formal OD training,

such as the

variety

of workshops offered by the National

Training Laboratories, the Center for

Creative Leadership,

the

Gestalt Institute, UCLA's Extension

Service, University Associates,

and others. Line

managers

increasingly

are attending such external programs.

Moreover, a growing number of

organizations, including

Texas

Instruments, Motorola, and General Electric,

have instituted in-house

training programs for

managers

to learn how to develop and

change their work units. As

managers gain OD competence,

they

become

its most basic

practitioners.

In

practice, the distinctions among the

three sets of OD practitioners are

blurring. A growing number of

managers

have transferred, either temporarily or

permanently, into the OD profession. For

example,

companies

such as Procter & Gamble have trained

and rotated managers into

full-time OD roles so

that

they

can gain skills and

experience needed for higher-level

management positions. Also, it is

increasingly

common

to find managers using their

experience in OD to become external

consultants. More OD

practitioners

are gaining professional competence in

related specialties, such as

business process

reengineering,

reward systems, and organization

design. Conversely, many

specialists in those related

areas

are

achieving professional competence in

OD. Cross-training and

integration are producing a

more

comprehensive

and complex kind of OD practitioner,

one with a greater diversity of

values, skills, and

experience

than a traditional

practitioner.

External

and Internal Practitioners:

In

every large-scale planned change

program, some person or

group is usually designated to

lead the

change;

sometimes it is the OD practitioner. The

practitioner then, is the change leader,

the person leading

or

guiding the process of change in an

organization. Internal practitioners are

already members of the

organization.

They may be either managers practicing OD

with their work groups or OD

specialists that

may

be from the human resources or

organization development department. External practitioners

are

brought

in from outside the organization as OD

specialists and are often

referred to as consultants. Both

the

use of external and internal

practitioners have advantages and

disadvantages.

The

OD practitioners who are specialists,

whether from within or outside of the

organization are

professionals

who have specialized and

trained in OD and related areas,

such as the social

sciences,

interpersonal

communications, decision making,

and organization behavior. These

specialists, often

referred

to as OD consultants, have a more

formal and involved process

when they enter the client

system

than

managers who are doing OD

with their work group.

Although much of the chapter is

directed at OD

practitioners

who are specialists, the

concepts also apply to OD practitioners

who are managers and

team

leaders

implementing OD.

The

External Practitioner:

The

external

practitioner is

someone not previously associated

with the client system. Coming from

the

outside,

the external practitioner sees things

from a different viewpoint

and from a position of

objectivity.

Because

external practitioners are invited into

the organization, they have increased

leverage (the degree of

influence

and status within the client

system) and greater freedom of

operation than internal

practitioners.

Research

evidence suggests that top

managers view external practitioners as having a

more positive role in

large-scale

change programs than

internal practitioners.

Since

external practitioners are not a part of

the organization, they are less in awe of

the power wielded by

various

organization members. Unlike internal

practitioners, they do not depend upon

the organization for

raises,

approval, or promotions. Because they

usually have a very broad career

base and other clients to

fall

back

on, they tend to have a more independent

attitude about risk-taking and

confrontations with the

client

system.

At McKinsey & Co., a leading

management consulting firm, consultants

are direct, outspoken, and

challenge

the client's opinions. Once

"The Firm" (as McKinsey is

called) is hired, a four- to

six-person

"engagement

team" is assembled, with an experienced

consultant to coordinate the effort. Bear in

mind,

though,

that McKinsey's

management consulting work is not

necessarily organization development.

The

disadvantages of external practitioners result

from the same factors as the

advantage. Outsiders

are

generally

unfamiliar with the organization system

and may not have

sufficient knowledge of its

technology,

such

as aerospace or chemistry. They

are unfamiliar with the culture,

communication networks, and formal

or

informal power systems. In some

situations, practitioners may have

difficulty gathering pertinent

information

simply because they are outsiders.

Our Changing World

illustrates problems that

outside

management

consulting firms face in Germany.

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

The

Internal Practitioner:

The

internal

practitioner is

already a member of the organization: a

top executive, an organization

member

who initiates change in his or

her work group, or a member of the

human resources or

organization

development department. Many large

organizations have established offices

with the specific

responsibility

of helping the organization implement change

programs. In the past few years, a

growing

number

of major organizations (including Disney,

IBM, General Electric, General Motors,

Honeywell,

Union

Carbide, and the US. Army

and Navy) have created

internal OD practitioner groups.

These internal

practitioners

often operate out of the

human resources area and

may report directly to the

president of the

organization.

Internal

practitioners have certain advantages

inherent in their relationship with the

organization. They are

familiar

with the organization's culture and

norms and probably accept

and behave in accordance

with the

norms.

This means that they need

not waste time becoming

familiar with the system and

winning

acceptance.

Internal practitioners know the power

structure, which are the

strategic people, and how

to

apply

leverage. They are already

known to the employees, and

have a personal interest in

seeing the

organization

succeed. Unfortunately, it is by no means

easy for internal practitioners to

acquire all the

skills

they

will need. The proof is in

the problems encountered by new, not

quite ready internal practitioners

or

managers

who take on projects before they

are fully comfortable with

their practitioner roles in

the

organization,

and before they understand and

have developed critical skills.

The

position of an internal practitioner

also has disadvantages. One of

these may be a lack of

the

specialized

skills needed for organization

development. The lack of OD skills

has become a less

significant

factor

now that more universities

have OD classes and programs

and their graduates have

entered the

workforce.

Another disadvantage relates to

lack of objectivity. Internal

practitioners may be more likely

to

accept

the organizational system as a given and

accommodate their change

tactics to the needs of

management.

Being known to the workforce

has advantages, but it can

also work against the

internal

practitioner.

Other employees may not

understand the practitioner's role and

will certainly be influenced by

his

or her previous work and relationships in

the organization, particularly if the work and

relationships

have

in anyway been questionable.

Finally, the internal practitioner

may not have the necessary

power and

authority;

internal practitioners are sometimes in a

remote staff position and

report to a mid-level

manager.

The

OD practitioner must break

through the barriers of bureaucracy

and organizational politics to

develop

innovation,

creativity, teamwork, and trust within

the organization.

The

External-Internal Practitioner

Team:

The

implementation of a large-scale change

program is almost impossible without the

involvement of all

levels

and elements of the organization. One

approach to creating a climate of

change uses a team

formed

of

an external practitioner working directly

with an internal practitioner to

initiate and facilitate

change

programs

(known as the external-internal

practitioner team).This is

probably the most effective

approach.

OD researcher John Lewis, for

example, found that

successful external OD practitioners

assisted

in

the development of their internal

counterparts. The partners

bring complementary resources to the

team;

each

has advantages and strengths

that offset the disadvantages

and weaknesses of the other.

The external

practitioner

brings expertise, objectivity,

and new insights to organization

problems. The

internal

practitioner,

on the other hand, brings

detailed knowledge of organization issues

and norms, a

long-rime

acquaintance

with members, and an

awareness of system strengths

and weaknesses. For change

programs

in

large organizations, the team

will likely consist of more

than two practitioners.

The

collaborative relationship between internal

and external practitioners provides an integration

of

abilities,

skills, and resources. The

relationship serves as a model for the

rest of the organization--a model

that

members can observe and see

in operation, one that

embodies such qualities as trust,

respect, honesty,

confrontation,

and collaboration. The team

approach makes it possible to

divide the change

program's

workload

and share in the diagnosis,

planning, and strategy. The

external-internal practitioner team

less

likely

to accept watered-down or compromised

change programs because each

team member provides

support

to the other. As an example, during the

U.S. Navy's Command

Development (OD) Program,

the

internal

change agents recommended

that training seminars be

conducted away from the

Navy

environment

(i.e., at a resort) and the participants

dress in civilian clothing to

lessen authority it

issues.

Higher

authority, however, ordered the seminars to he held on

naval bases and in

uniform--ground rules

that

the internal practitioners reluctantly accepted. In

this situation an external practitioner with

greater

leverage

might have provided enough support

and influence to gain approval to the

desired program.

Another

reason for using an external-internal

practitioner team is to achieve

greater continuity over

the

entire

OD program. Because external practitioners

are involved in other

outside activities, they generally

are

available

to the organization only a few days a

month, with two- or

three-week intervals between visits.

The

internal

practitioner, on the other hand, provides

a continuing point of contact

for organization members

whenever

problems or questions arise.

Because many OD programs are

long-term efforts, often

lasting

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

three

to five Years, the external-internal

combination may provide the

stimulation and motivation

needed

to

keep the change program moving

during periods of resistance.

The team effort is probably

the most

effective

approach because it combines the

advantages of both external and

internal practitioners while

minimizing

the disadvantages.

Practitioner

Style Model:

There

is often a gap between the practitioner's

and the client's understandings

about OD and change.

The

practitioner

needs to assess the degree of this

gap, because a relationship is possible

only if the practitioner

can

be flexible enough to understand

where the client is and help

the client to learn about the OD

change

process.

In this sense, the practitioner must

have clarity about the purpose of OD in

the organization. The

practitioner

brings certain knowledge, skills,

values, and experience to the situation.

In turn, the client

system

has its own values

and a set of expectations

for the practitioner. The

target organization within the

client

system has its own

subculture and level of readiness

for change.

The

practitioner's task and the scope,

difficulty, and complexity of the

changes to be implemented affect

the

relationship as well. Finally, the target

organization's readiness, for change,

level of resistance, and

culture

also influence the practitioner's style

and the change approaches

that may be successful in a

given

situation.

The OD practitioner needs to

involve organization members at all

levels and convince them to

"buy

in" on the change program--in effect, to

get involved in soling the

problems.

Developing

a Trust Relationship:

The

development of openness and trust between

practitioner and client is an essential

aspect of the OD

program.

It is important because trust is

necessary for cooperation and

communication. When there is no

trust,

people will tend to be dishonest,

evasive, and not authentic

with one another, and communication

is

often

inaccurate, distorted, or incomplete. There are

several basic responses that

the practitioner may use

in

the

communication process aimed at developing

a trust relationship:

�

Questions

--"How do

you see the organization?"

�

Applied

expertise (advising) --"One

possible intervention is team

building."

�

Reflection

"It

sounds like you would

like to see a participative form of

leadership."

�

Interpretation

--"From

your description, inter-team conflict could be the

problem."

�

Self-disclosure

--"I've

felt discouraged myself when my

ideas were rejected."

�

Silence

--Say

nothing, let the client sort

out his or her

thoughts.

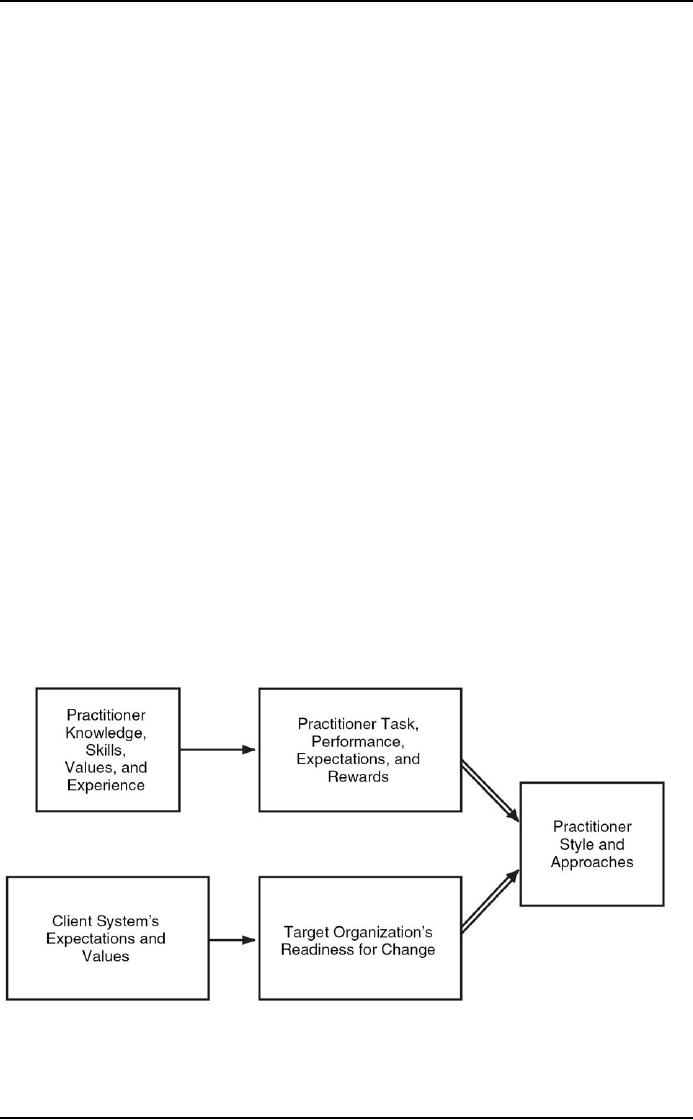

Figure:

09 Practitioner Style Model

How

these basic responses are

used is important in developing the

practitioner-client relationship, in

general

the more balanced the practitioner's use

of these responses and the

more open the range of

responses,

the higher level of trust. For example,

some practitioners rely almost

exclusively on questions

without

sharing their own ideas

and feelings. This tends to

create a one-way flow of

information. Other

Organization

Development MGMT

628

VU

practitioners

rely heavily on advising responses, which

may tend to develop a dependency

relationship. It is

important

for the practitioner to be aware of the

range of responses and to

use those that will

build an

open

and trusting relationship.

During

the first several contacts

with the client system, the

following types of questions

may be reflected

upon:

�

What

is the attitude of the client system

toward OD? Is there a real

underlying desire for

change?

Or

is the attitude superficial?

�

What

is the gut-level meaning of the client's

problem? How realistic is the

client's appraisal of

its

own

problems?

�

What

are the possibilities that an OD program

will alleviate the problem?

Can OD solve the

problem

or are other change programs

more appropriate?

�

What

is the practitioner's potential impact on the

system? Based on feedback

from the client, how

probable

is it that the practitioner can

bring about significant

change?

Once

these questions are

answered, the practitioner can

decide whether to continue the change

efforts or

to

discontinue and terminate the relationship. Most OD

practitioners recommend an open discussion

with

the

client on these issues at an early

stage.

Table of Contents:

- The Challenge for Organizations:The Growth and Relevance of OD

- OD: A Unique Change Strategy:OD consultants utilize a behavioral science base

- What an “ideal” effective, healthy organization would look like?:

- The Evolution of OD:Laboratory Training, Likert Scale, Scoring and analysis,

- The Evolution of OD:Participative Management, Quality of Work Life, Strategic Change

- The Organization Culture:Adjustment to Cultural Norms, Psychological Contracts

- The Nature of Planned Change:Lewin’s Change Model, Case Example: British Airways

- Action Research Model:Termination of the OD Effort, Phases not Steps

- General Model of Planned Change:Entering and Contracting, Magnitude of Change

- The Organization Development Practitioner:External and Internal Practitioners

- Creating a Climate for Change:The Stabilizer Style, The Analyzer Style

- OD Practitioner Skills and Activities:Consultant’s Abilities, Marginality

- Professional Values:Professional Ethics, Ethical Dilemmas, Technical Ineptness

- Entering and Contracting:Clarifying the Organizational Issue, Selecting an OD Practitioner

- Diagnosing Organizations:The Process, The Performance Gap, The Interview Data

- Organization as Open Systems:Equifinality, Diagnosing Organizational Systems

- Diagnosing Organizations:Outputs, Alignment, Analysis

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Outputs

- Diagnosing Groups and Jobs:Design Components, Fits

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Methods for Collecting Data, Observations

- Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic information:Sampling, The Analysis of Data

- Designing Interventions:Readiness for Change, Techno-structural Interventions

- Leading and Managing Change:Motivating Change, The Life Cycle of Resistance to Change

- Leading and managing change:Describing the Core Ideology, Commitment Planning

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Measurement

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions:Research Design

- Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization Development Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Group Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Leadership and Authority, Group Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Third-Party Interventions

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Building, Team Building Process

- Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches:Team Management Styles

- Organization Process Approaches:Application Stages, Microcosm Groups

- Restructuring Organizations:Structural Design, Process-Based Structures

- Restructuring Organizations:Downsizing, Application Stages, Reengineering

- Employee Involvement:Parallel Structures, Multiple-level committees

- Employee Involvement:Quality Circles, Total Quality Management

- Work Design:The Engineering Approach, Individual Differences, Vertical Loading

- Performance Management:Goal Setting, Management by Objectives, Criticism of MBO

- Developing and Assisting Members:Career Stages, Career Planning, Job Pathing

- Developing and Assisting Members:Culture and Values, Employee Assistance Programs

- Organization and Environment Relationships:Environmental Dimensions, Administrative Responses

- Organization Transformation:Sharing the Vision, Three kinds of Interventions

- The Behavioral Approach:The Deep Assumptions Approach

- Seven Practices of Successful Organizations:Training, Sharing Information