|

Principles

of Marketing MGT301

VU

Lesson

25

Lesson

overview and learning objectives:

In

last Lesson we discussed the

price its definition, focused on

the problem of setting prices

and

considered

the factors marketers must

consider when setting prices today we

will look at general

pricing

approaches, we will also

examine pricing strategies

for new-product pricing,

product mix

pricing.

PRICE

THE 2ND P OF MARKETING MIX.

A.

Setting

Pricing Policy

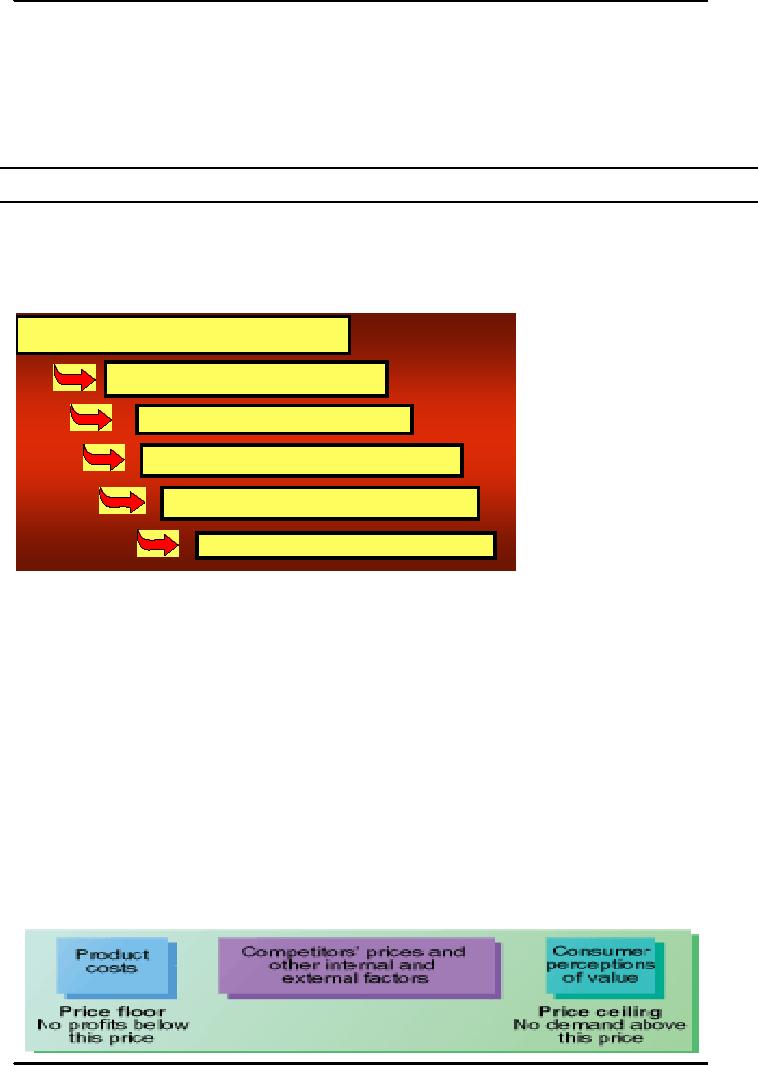

Pricing

policy setting starts with setting

the pricing objective that

can be: Profit

Oriented

(concerned

with increase in profit),

Sales Oriented (basically concerned

with increase in sales)

and

Status

Quo Oriented. Whereas costs

set the lower limit of

prices, the market and

demand set the

upper

limit.

Both

consumer

and industrial

1

. S e le c tin g t h e p r ic in g o b je c tiv e

buyers

balance the price

of

a product or service

2

. D e te r m in in g d e m a n d

against

the benefits of

owning

it. Thus, before

3

. E s tim a tin g c o s ts

setting

prices,

the

marketer

must

4

. A n a ly z in g c o m p e tito r s '

c

o s ts , p r ic e s , a n d o ffe r s

understand

the

relationship

between

5

. S e le c tin g a p r ic in g m e th o d

price

and demand for its

product.

In this section,

6

. S e le c tin g fin a l p r ic e

we

explain how

the

pricedemand

relationship

varies for different types

of markets and how buyer

perceptions of price affect

the

pricing

decision. Costs set the

floor for the price

that the company can

charge for its product.

The

company

wants to charge a price that

both covers all its costs

for producing, distributing,

and

selling

the product and delivers a

fair rate of return for its

effort and risk. A company's costs

may

be

an important element in its pricing strategy.

Companies with lower costs

can set lower

prices

that

result in greater sales and

profits. Company's pricing decisions

are also affected by

competitors'

costs and prices and

possible competitor reactions to

the company's own

pricing

moves

there fore while setting the

prices theses facts should

also kept in mind. Final

step is setting

the

final price by using different

methods.

B.

General Pricing Approaches

The

price the company charges

will be somewhere between one

that is too low to produce a

profit

and

one that is too high to produce any

demand. Figure summarizes the

major considerations in

setting

price. Product costs set a

floor to the price; consumer perceptions

of the product's value

set

the

ceiling. The company must

consider competitors' prices

and other external and

internal factors

to

find the best price

between these two extremes.

Companies set prices by

selecting a general

119

Principles

of Marketing MGT301

VU

pricing

approach that includes one or more of

three sets of factors. We examine

these approaches:

the

cost-based

approach (cost-plus

pricing, break-even analysis,

and target profit pricing);

the buyer-

based

approach (value-based

pricing); and the competition-based

approach (going-rate

and sealed-bid

pricing).

a)

Cost-Based Pricing

Cost-Plus

Pricing

The

simplest pricing method is

cost-plus pricing--adding a standard

markup to the cost of

the

product.

Construction companies, for

example, submit job bids by

estimating the total project

cost

and

adding a standard markup for

profit. Lawyers, accountants, and

other professionals

typically

price

by adding a standard markup to

their costs. Some sellers

tell their customers they

will charge

cost

plus a specified markup; for

example, aerospace companies

price this way to the

government.

To

illustrate markup pricing,

suppose any manufacturer had

the following costs and

expected sales:

Then

the manufacturer's cost per

toaster is given by:

Unit

Cost = variable Cost + Fixed

Cost

---------------

Price

- Variable Cost

The

manufacturer's markup price is given

by:

Markup

Price

=

Unit

Cost

---------------

(1-desired

return on sale)

Do

using standard markups to set prices

make sense? Generally, no.

Any pricing method

that

ignores

demand and competitor prices

is not likely to lead to the

best price. Markup pricing

works

only

if that price actually brings in

the expected level of sales.

Still, markup pricing

remains popular

for

many reasons. First, sellers

are more certain about costs

than about demand. By tying

the price

to

cost, sellers simplify

pricing--they do not have to

make frequent adjustments as

demand

changes.

Second, when all firms in

the industry use this

pricing method, prices tend

to be similar

and

price competition is thus

minimized. Third, many

people feel that cost-plus

pricing is fairer to

both

buyers and sellers. Sellers

earn a fair return on their

investment but do not take

advantage of

buyers

when buyers' demand becomes

great.

Break-even

Analysis and Target Profit

Pricing

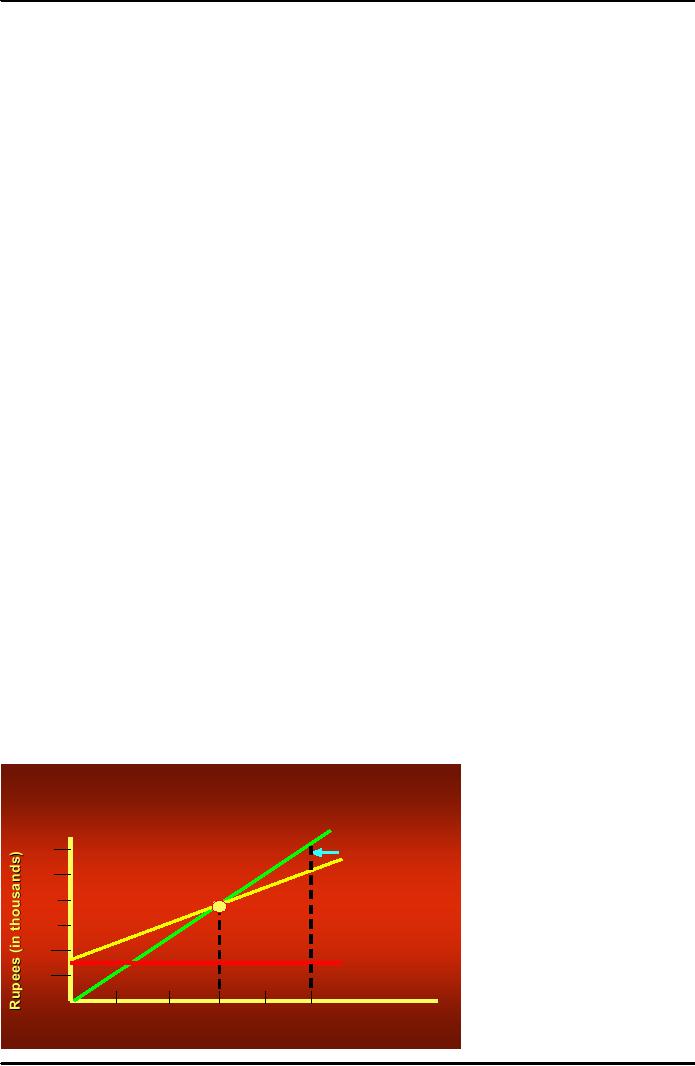

Another

cost-oriented pricing approach is

break-even pricing(or a variation

called target profit

pricing

he firm tries to determine the

price at which it will break

even or make the target

profit it is

seeking.

This pricing method is also

used by public utilities,

which are constrained to make a

fair

return

on their investment.

Target

pricing uses the

concept

of

a break-even

chart, which

T

o ta l re v e n u e

shows

the total cost and

total

T

a rg e t p ro fit

1200

revenue

expected at different

T

o ta l c o s t

sales

volume levels. Figure

1000

B

r e a k -e v e n p o in t

shows

a break-even point.

800

Fixed

costs are same

regardless

600

of

sales volume. Variable

costs

400

are

added to fixed costs

to

F

ix e d c o s t

form

total costs, which

rise

200

with

volume. The total

revenue

0

curve

starts at zero and

rises

10

20

30

40

50

S

a le s v o l u m e in u n it s ( t h o u s a n d s )

with

each unit sold.

120

Principles

of Marketing MGT301

VU

Fixed

Cost

Break-even

Volume =

---------------

Price

- Variable Cost

The

manufacturer should consider

different prices and

estimate break-even volumes,

probable

demand,

and profits for

each.

b)

Value-Based Pricing

An

increasing number of companies

are basing their prices on

the product's perceived

value.

Value-based

pricing uses buyers' perceptions of value,

not the seller's cost, as

the key to pricing.

Value-based

pricing means that the

marketer cannot design a product

and marketing program and

then

set the price. Price is

considered along with the

other marketing mix variables

before

the

marketing

program is set.

Figure

compares cost-based pricing

with value-based pricing.

Cost-based pricing is product

driven.

The

company designs what it

considers to be a good product,

totals the costs of making

the

product,

and sets a price that

covers costs plus a target

profit. Marketing must then

convince

buyers

that the product's value at

that price justifies its

purchase. If the price turns

out to be too

high,

the company must settle

for lower markups or lower

sales, both resulting in

disappointing

profits.

Cost-based

versus value-based

pricing

Value-based

pricing reverses this

process. The company sets

its target price based on

customer

perceptions

of the product value. The

targeted value and price

then drive decisions about

product

design

and what costs can be

incurred. As a result, pricing

begins with analyzing consumer

needs

and

value perceptions, and price is set to

match consumers' perceived value.

A

company using value-based pricing

must find out what value

buyers assign to different

competitive

offers. However, measuring

perceived value could be difficult.

Sometimes, consumers

are

asked how much they

would pay for a basic

product and for each

benefit added to the

offer.

Or

a company might conduct experiments to

test the perceived value of

different product

offers.

If

the seller charges more

than the buyers' perceived value,

the company's sales will

suffer. Many

companies

overprice their products, and

their products sell poorly.

Other companies under

price.

Under

priced products sell very

well, but they produce less

revenue than they would have

if price

were

raised to the perceived-value

level.

During

the past decade, marketers

have noted a fundamental

shift in consumer attitudes toward

price

and quality. Many companies

have changed their pricing

approaches to bring them

into line

with

changing economic conditions and consumer

price perceptions. The best way to

hold your

customers

is to constantly figure out

how to give them more

for less."

Thus,

more and more, marketers

have adopted value pricing

strategies--offering just the

right

combination

of quality and good service

at a fair price. In many

cases, this has involved

the

introduction

of less expensive versions of

established, brand-name products. In many

business-to-

business

marketing situations, the pricing

challenge is to find ways to

maintain the company's

121

Principles

of Marketing MGT301

VU

pricing

power--its

power to maintain or even

raise prices without losing market

share. To retain

pricing

power--to escape price

competition and to justify

higher prices and margins--a

firm must

retain

or build the value of its marketing

offer. This is especially

true for suppliers of

commodity

products,

which are characterized by

little differentiation and

intense price competition. In

such

cases,

many companies adopt value-added

strategies.

Rather than cutting prices

to match

competitors,

they attach value-added services to

differentiate their offers

and thus support

higher

margins.

c)

Competition-Based Pricing

Consumers

will base their judgments of

a product's value on the prices

that competitors charge

for

similar

products. One form of competition-based

pricing is going-rate

pricing, in

which a firm bases

its

price largely on competitors' prices,

with less attention paid to

its own costs or to demand.

The

firm

might charge the same,

more, or less than its major

competitors. In oligopolistic

industries

that

sell a commodity such as steel,

paper, or fertilizer, firms

normally charge the same

price. The

smaller

firms follow the leader:

They change their prices

when the market leader's

prices change,

rather

than when their own

demand or costs change. Some

firms may charge a bit

more or less,

but

they hold the amount of

difference constant. Thus, minor

gasoline retailers usually

charge a

few

cents less than the

major oil companies, without

letting the difference

increase or decrease.

Going-rate

pricing is quite popular.

When demand elasticity is hard to

measure, firms feel that

the

going

price represents the

collective wisdom of the

industry concerning the

price that will yield

a

fair

return. They also feel that

holding to the going price

will prevent harmful price

wars.

Competition-based

pricing is also used when

firms bid

for

jobs. Using sealed-bid

pricing, a firm

bases

its

price on how it thinks

competitors will price

rather than on its own costs

or on the demand.

The

firm wants to win a contract,

and winning the contract

requires pricing less than

other firms.

Yet

the firm cannot set its

price below a certain level. It

cannot price below cost

without harming

its

position. In contrast, the

higher the company sets its

price above its costs, the

lower its chance

of

getting the contract.

Pricing

decisions are subject to an incredibly

complex array of environmental

and competitive

forces.

A company sets not a single

price, but rather a

pricing

structure that

covers different items

in

its

line. This pricing structure

changes over time as

products move through their

life cycles. The

company

adjusts product prices to

reflect changes in costs and

demand and to account

for

variations

in buyers and situations. As the

competitive environment changes,

the company

considers

when to initiate price

changes and when to respond to

them.

C.

New-Product Pricing

Strategies

Pricing

strategies usually change as

the product passes through

its life cycle. The

introductory stage

is

especially challenging. Companies

bringing out a new product

face the challenge of setting

prices

for

the first time. They

can choose between two broad

strategies: market-skimming

pricing and

market-

penetration

pricing.

a)

Market-Skimming Pricing

Many

companies that invent new

products initially set high

prices to "skim" revenues

layer by layer

from

the market. Intel is a prime

user of this strategy, called

market-skimming

pricing.

Market

skimming

makes sense only under

certain conditions. First, the

product's quality and image

must

support

its higher price, and enough

buyers must want the product

at that price. Second, the

costs

of

producing a smaller volume cannot be so

high that they cancel

the advantage of charging

more.

Finally,

competitors should not be

able to enter the market

easily and undercut the

high price.

b)

Market-Penetration

Pricing

Rather

than setting a high initial

price to skim

off

small but profitable market segments,

some

companies

use market-penetration

pricing.

They set a low initial

price in order to penetrate

the

market

quickly and deeply--to

attract a large number of buyers

quickly and win a large

market

share.

The high sales volume

results in falling costs, allowing

the company to cut its price

even

122

Principles

of Marketing MGT301

VU

further.

Several conditions must be

met for this low-price

strategy to work. First, the

market must

be

highly price sensitive so

that a low price produces

more market growth. Second,

production and

distribution

costs must fall as sales

volume increases. Finally,

the low price must

help keep out

the

competition,

and the penetration pricer

must maintain its low-price

position--otherwise, the

price

advantage

may be only

temporary.

D.

Product Mix Pricing Strategies

The

strategy for setting a product's

price often has to be

changed when the product is

part of a

product

mix. In this case, the

firm looks for a set of

prices that maximizes the

profits on the total

product

mix. Pricing is difficult because

the various products have

related demand and costs

and

face

different degrees of competition. We

now take a closer look at

the five product mix

pricing

situations

a)

Product Line Pricing

Companies

usually develop product lines

rather than single products.

In product line

pricing,

management

must decide on the price

steps to set between the

various products in a line.

The

price steps should take

into account cost differences

between the products in the

line,

customer

evaluations of their different features,

and competitors' prices. In

many industries, sellers

use

well-established price

points for

the products in their line.

The seller's task is to

establish

perceived

quality differences that support

the price differences.

b)

Optional-Product Pricing

Many

companies use optional-product

pricing--offering to sell optional or

accessory products

along

with their main product.

For example, a car buyer

may choose to order power

windows,

cruise

control, and a CD changer. Pricing these

options is a sticky problem. Automobile

companies

have

to decide which items to

include in the base price

and which to offer as

options. Until recent

years,

The economy model was

stripped of so many comforts and

conveniences that most

buyers

rejected

it.

c)

Captive-Product Pricing

Companies

that make products that

must be used along with a

main product are using

captive-

product

pricing. Examples of captive products are

razor blades, camera film,

video games, and

computer

software. Producers of the main

products (razors, cameras, video game

consoles, and

computers)

often price them low

and set high markups on the

supplies. Thus,

camera

manufactures

price its cameras low

because they make its money

on the film it sells. In the

case of

services,

this strategy is called

two-part

pricing. The

price of the service is

broken into a fixed

fee plus

a

variable

usage rate. Thus,

a telephone company charges a monthly

rate--the fixed fee--plus

charges

for

calls beyond some minimum

number--the variable usage

rate. Amusement parks

charge

admission

plus fees for food,

midway attractions, and rides

over a minimum. The service

firm must

decide

how much to charge for

the basic service and

how much for the

variable usage. The

fixed

amount

should be low enough to induce

usage of the service; profit

can be made on the

variable

fees.

d)

By-Product Pricing

In

producing processed meats,

petroleum products, chemicals,

and other products, there

are often

by-products.

If the by-products have no value

and if getting rid of them is

costly, this will

affect

the

pricing of the main product.

Using by-product pricing,

the manufacturer will seek a

market for

these

by-products and should

accept any price that covers

more than the cost of

storing and

delivering

them. This practice allows

the seller to reduce the

main product's price to make

it more

competitive.

By-products can even turn

out to be profitable. For

example, many lumber mills

have

begun

to sell bark chips and

sawdust profitably as decorative

mulch for home and

commercial

landscaping.

Sometimes,

companies don't realize how

valuable their by-products

are.

123

Principles

of Marketing MGT301

VU

e)

Product

Bundle Pricing

Using

product bundle pricing,

sellers often combine several of

their products and offer

the bundle

at

a reduced price. Thus,

theaters and sports teams

sell season tickets at less

than the cost of

single

tickets;

hotels sell specially priced

packages that include room,

meals, and entertainment;

computer

makers

include attractive software packages

with their personal computers.

Price bundling can

promote

the sales of products consumers

might not otherwise buy, but

the combined price

must

be

low enough to get them to

buy the bundle.

124

Table of Contents:

- PRINCIPLES OF MARKETING:Introduction of Marketing, How is Marketing Done?

- ROAD MAP:UNDERSTANDING MARKETING AND MARKETING PROCESS

- MARKETING FUNCTIONS:CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP MANAGEMENT

- MARKETING IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE AND EVOLUTION OF MARKETING:End of the Mass Market

- MARKETING CHALLENGES IN THE 21st CENTURY:Connections with Customers

- STRATEGIC PLANNING AND MARKETING PROCESS:Setting Company Objectives and Goals

- PORTFOLIO ANALYSIS:MARKETING PROCESS,Marketing Strategy Planning Process

- MARKETING PROCESS:Analyzing marketing opportunities, Contents of Marketing Plan

- MARKETING ENVIRONMENT:The Company’s Microenvironment, Customers

- MARKETING MACRO ENVIRONMENT:Demographic Environment, Cultural Environment

- ANALYZING MARKETING OPPORTUNITIES AND DEVELOPING STRATEGIES:MIS, Marketing Research

- THE MARKETING RESEARCH PROCESS:Developing the Research Plan, Research Approaches

- THE MARKETING RESEARCH PROCESS (Continued):CONSUMER MARKET

- CONSUMER BUYING BEHAVIOR:Model of consumer behavior, Cultural Factors

- CONSUMER BUYING BEHAVIOR (CONTINUED):Personal Factors, Psychological Factors

- BUSINESS MARKETS AND BUYING BEHAVIOR:Market structure and demand

- MARKET SEGMENTATION:Steps in Target Marketing, Mass Marketing

- MARKET SEGMENTATION (CONTINUED):Market Targeting, How Many Differences to Promote

- Product:Marketing Mix, Levels of Product and Services, Consumer Products

- PRODUCT:Individual product decisions, Product Attributes, Branding

- PRODUCT:NEW PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT PROCESS, Idea generation, Test Marketing

- NEW PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT:PRODUCT LIFE- CYCLE STAGES AND STRATEGIES

- KEY TERMS:New-product development, Idea generation, Product development

- Price the 2nd P of Marketing Mix:Marketing Objectives, Costs, The Market and Demand

- PRICE THE 2ND P OF MARKETING MIX:General Pricing Approaches, Fixed Cost

- PRICE THE 2ND P OF MARKETING MIX:Discount and Allowance Pricing, Segmented Pricing

- PRICE THE 2ND P OF MARKETING MIX:Price Changes, Initiating Price Increases

- PLACE- THE 3RD P OF MARKETING MIX:Marketing Channel, Channel Behavior

- LOGISTIC MANAGEMENT:Push Versus Pull Strategy, Goals of the Logistics System

- RETAILING AND WHOLESALING:Customer Service, Product Line, Discount Stores

- KEY TERMS:Distribution channel, Franchise organization, Distribution center

- PROMOTION THE 4TH P OF MARKETING MIX:Integrated Marketing Communications

- ADVERTISING:The Five M’s of Advertising, Advertising decisions

- ADVERTISING:SALES PROMOTION, Evaluating Advertising, Sales Promotion

- PERSONAL SELLING:The Role of the Sales Force, Builds Relationships

- SALES FORCE MANAGEMENT:Managing the Sales Force, Compensating Salespeople

- SALES FORCE MANAGEMENT:DIRECT MARKETING, Forms of Direct Marketing

- DIRECT MARKETING:PUBLIC RELATIONS, Major Public Relations Decisions

- KEY TERMS:Public relations, Advertising, Catalog Marketing

- CREATING COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE:Competitor Analysis, Competitive Strategies

- GLOBAL MARKETING:International Trade System, Economic Environment

- E-MARKETING:Internet Marketing, Electronic Commerce, Basic-Forms

- MARKETING AND SOCIETY:Social Criticisms of Marketing, Marketing Ethics

- MARKETING:BCG MATRIX, CONSUMER BEHAVIOR, PRODUCT AND SERVICES

- A NEW PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT:PRICING STRATEGIES, GLOBAL MARKET PLACE