|

THE EFFICIENT MARKET HYPOTHESIS (EMH) |

| << COMMON STOCK: ANALYSIS AND STRATEGY |

| Behavioral Finance >> |

Investment

Analysis & Portfolio Management

(FIN630)

VU

Lesson

# 23

MARKET

EFFICIENCY

The

fair price function of the

capital markets provides

assurance that investors can

sell stock

at

the going price and not be

taken to the cleaners. A discussion of

fair pricing

inevitably

leads

to the efficient market

hypothesis (EMH), the theory

supporting the nation that

market

prices

are in fact fair. The EMH is

probably the single most

important paradigm in

finance.

Like

technical analysis, market

efficiency is a controversial part of

finance. In an efficient

market

security prices are based on

the available information so as to

offer and expected

return

consistent with their level

of risk. While most professors

are convinced that

the

markets

are quite efficient and that

free lunches are as scarce

as Ty Cobb baseball cards,

some

professional money managers

believe otherwise. Capital

market prices are presumed

to be

fair because they are

the equilibrium result of

the analyses of many people, each

of

whom

is seeking to increase personal wealth.

When a listed stock is put

up for sale,

hundreds

of people can bid for it.

The markets ensure that the

seller trades with the

highest

bidder.

Conversely, a buyer is confronted

with numerous potential

sellers, and the

system

ensures

that the buyer's order is

matched up with the best

price, which from the

buyer's

perspective

is the lowest price. The

greater the number of participants and

the more formal

the

marketplace, the more an

investor is assured of a good (fair)

price.

THE

EFFICIENT MARKET HYPOTHESIS

(EMH):

To

speak intelligently about

the efficient market

hypothesis a person must under-stand

what

the

hypothesis says and what it

does not say. Efficiency can

be categorized by both type

and

degree.

Types

of Efficiency:

The

two types of efficiency are

operational efficiency and informational

efficiency.

Operational

efficiency is a measure of how

well things function in

terms of speed of

execution

and accuracy. At a stock exchange,

operational efficiency is measured by

such

factors

as the number of orders lost or

filled incorrectly and the

elapsed time between

the

receipt

of an order and its execution. All

market participants are

concerned with these

matters,

but the EMH does not

refer to this type of

efficiency.

Informational

efficiency is a measure of how

quickly and accurately the

market1 reacts to

new

information. New data

constantly enter the

marketplace via economic

reports, company

announcements,

political statements, or public opinion

surveys, to name a few sources.

What

does all this information

mean? Is raising unemployment in

the United Kingdom

good

or

bad for holders of U.S.

Treasury bonds? How about a

company's announcement that

it

intends

to split its stock five

for one? Suppose the

price of gold jumps $10 an

ounce in one

day,

what effect, if any, is this

event likely to have on

stock prices?

We

know security prices adjust

rapidly and accurately to the

news without the need

to

digest it

very long. Sometimes the

speed of adjustment is remarkably

fast. For instance,

the

author

was once sitting in a brokerage firm

punching up his current

stock on the Quotron

machine.

One of his holding was

common stock in MGM Grand

Hotel. The stock was

trading

at $10�. At that very

moment, across the room,

the bell rang and the red

light

flashed

on the Dow Jones News

Service monitor, indicating

hot news. The headline

read,

"Fire

at the MGM Grand Hotel". In

the seconds it took the

author to walk from the

service

142

Investment

Analysis & Portfolio Management

(FIN630)

VU

monitor

back to the Quotron machine,

the stock fell to $7�,

which is approximately

where

it

remained the rest of the

day.

One

need not be a Mensa member

to realize that a hotel fire

is bad news. In an

informationally

efficient market, prices are

going to react fast, just as

they did in the MGM

situation.

An investor cannot expected to read

about the fire in The

Wall Street journal

the

following

day and think, "Well, I'll bet

that hammers the stock; I'd

better sell," and

then

expect

to find that the market is

still trying to sort out

the news. Prices would

have dropped

long

ago.

Because

the market is efficient, the

meaning of the news is

discovered quickly, and prices

adjust.

Students in an investments course are

sometimes disappointed to learn that

simply

taking

a stock market course does

not ordain them with

the power to read the

financial

pages

and fluently pick stocks that will

double in price by next

week. Things do not

work

that

way.

Still,

the market is not completely

efficient. It still rewards people

who process the

news

better

than the next person. For

one thing, not everyone has

access to the same news,

nor

does

everyone receive the news in

a timely fashion. Because of

this discrepancy,

market

participants

commonly talk about three

forms of the EMH, each of

which is based on the

availability

of a different level of

information.

The

efficient market hypothesis is one of

the most important paradigms in

finance.

The

efficient market hypothesis

deals with informational

efficiency, which is a measure

of

how

quickly and accurately the

market digests new

information. It is well established

that

the

market is informationally

efficient.

Degrees

of Informational Efficiency:

1.

Weak form

Efficiency:

The

least restrictive form of the EMH is

weak form efficiency, which

states that future

stock

prices

cannot be predicted by analyzing

price from the past. In

other words, charts are of

no

use

in predicting future prices.

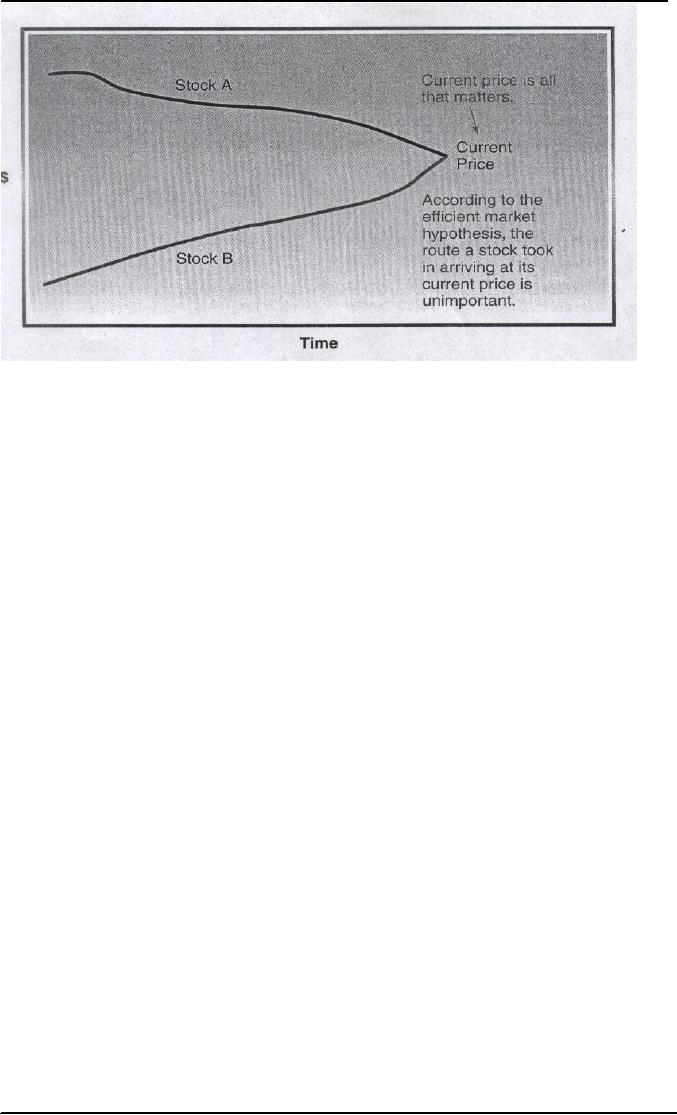

According

to the weak form of the

EMH, how a stock arrived at

its current price is

irrelevant.

It could have followed the

route of Stock A, or it could

have behaved like

Stock

B.

The only thing that

matters is the current

price. Any information contained in

the past

price

series is already included in

the current price.

The

realization is a difficult pill

for most people to swallow. A

survey of a variety of people

would

reveal that virtually

everyone would identify

stock B as clearly a better

buy than

stock

A. After all, B is "rising"

while A is "falling". Who

would want to buy a

declining

stock?

143

Investment

Analysis & Portfolio Management

(FIN630)

VU

The

point that is missed in this

logic was made earlier: past

prices do not matter; future

ones

do.

Everyone has access to past

price information2.

According to the EMH, so

many people

are

looking at these same

numbers that any "free

lunches" have already been

consumed.

The

current price is a fair one

that takes into account

any information contained in

the past

price

data.

Human

nature is prone to extrapolate

the past into the

future. Business Week conducted

a

poll3 in late 1999 asking investors

their views on the stock

market. Fifty-eight

percent

indicated

they believed the stock

market was "very" or "somewhat"

overpriced, but 52

percent

of the respondents believed that stocks

would be higher a year

later. Respondents

aged

18 to 24 were most bullish,

with 63 percent predicting

the market would be higher

in

2000.

Oddly, though, 67 percent of

this same group predicted a

market crash in the

coming

year.

Charting

is a topic discussed in hundreds of

books. In the same way we

look for identifiable

forms

in the clouds or in star constellations,

our brains are creative

enough to find

patterns

in a

sequence of stock prices. Technical

analysts learn "important"

patterns through

folklore

or

their own

imagination.

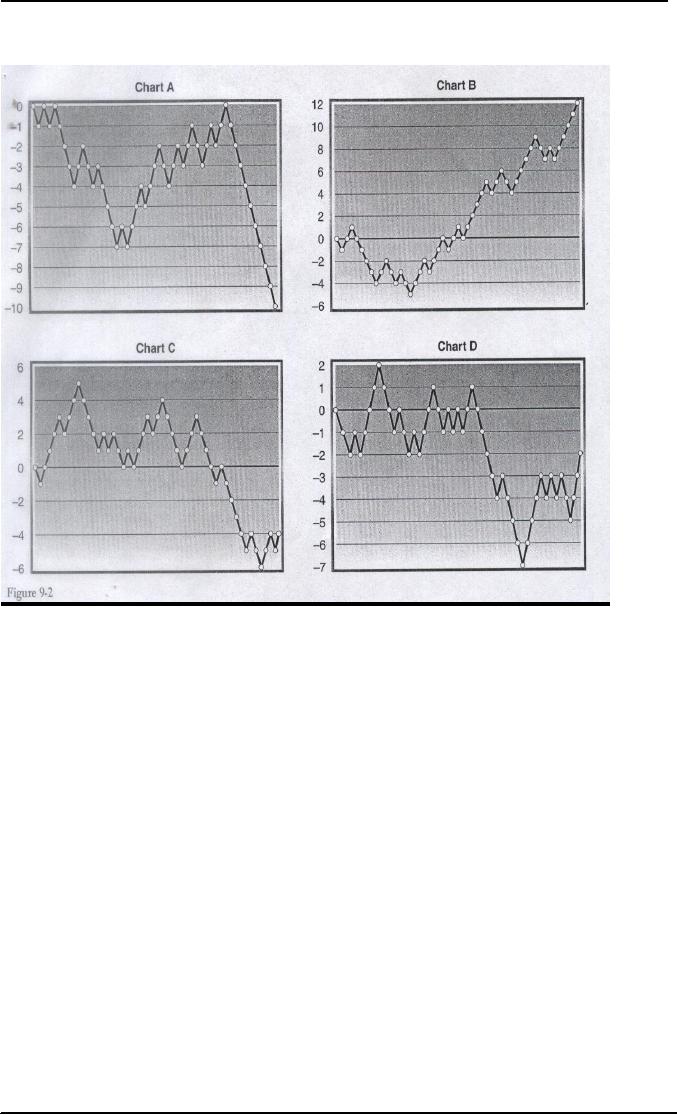

Look

at the four graphs in Figure

9-2. Are these random

patterns, or is one or more of

them

revealing

something? Some technical

analysts would look at Chart

A and see a stock

that

has

been unsuccessful in penetrating a

"resistance level" at 0. Its failure to

rise above this

point

after several attempts is

followed by a major downturn in

the stock price.

Chart

B shows a pattern that looks

appealing. This stock is on a sustained

rise. Chart C

shows

a bearish situation. Here a stock

has penetrated its support

level at 0, resulting in a

significant

decline to the -5 area. A

technical analyst would call

this a breakout on

the

downside.

Chard D shows congestion in

the -2 to +1 range, followed by a sharp break to

a

new

equilibrium level around

-4.

What

do these patterns mean?

Would an investor be more

inclined to buy one of

these

stocks

than the others? Is one clearly

inferior to the others? Actually,

each of these figures

was

created using the random

number generating function of

Lotus 1-2-3. These are

four

successive

Lotus graph; each graph

has a different seed number

to start its series. In all

four

graph,

each observation is either one

unit greater than the

previous observation or one

unit

144

Investment

Analysis & Portfolio Management

(FIN630)

VU

smaller,

and each of the two possible

out-comes had a 50 percent probability of

occurring.

Are

these graphs useful in predicting

what Lotus will select next?

Probably not.

Past

prices do not matter; future

ones do. Weak form

efficiency

145

Investment

Analysis & Portfolio Management

(FIN630)

VU

Table

9-2 shows the procedures for

the test.

146

Investment

Analysis & Portfolio Management

(FIN630)

VU

when

they rise x percent from a subsequent

low. Because anyone can

calculate these

realized

percentages, filter rules

should not work if the

markets are weak form

efficient.

Fama

also investigated the performance of

filter rules, as have

numerous other

researchers.

The

results are similar to those of

the autocorrelation tests. Occasionally

one reads reports

of

successful filters, but they

still prove uneconomic when

the effect of transaction

costs is

included.

The

evidence against predictive chart

patterns and valuable filter

rules is so powerful

that

anything

new about this topic

seldom appears in the

finance literature. People

who review

articles

for the various academic

journals have seen

overwhelming evidence that

the market

is

weak form efficient, and

editors rarely want to

devote space to another

article confirming

decades

of prior work in this

area.

2.

Semi-strong Form:

The

weak form of the EMH states

that security prices fully reflect

any information

contained

in the past series of stock

prices. Semi-strong form efficiency

takes the

information

set s step further and

includes all publicly

available information. The

semi-

strong

form of the EMH states that

security prices fully reflect all

relevant publicly

available

information.

A

plethora of information holds

potential interest to investors. In

addition to past

stock

prices,

economic reports, brokerage firm

recommendations, investment advisory

letters, and

so on

all contain a myriad of

details about what affects

business performance and

stock

value.

While no one sees every one of

these items, the market

does, and prices move as

people make

decisions to buy and sell based on

what they learn from

the information set

available

to them.

The

news item about the MGM

Grand Hotel fire was not

past price data, but it was

publicly

available

and the stock did decline

because of it. According to

the semi-strong form of

the

EMH,

this behavior is exactly

what is expected.

Semi-strong

form efficiency states that

security prices reflect all

publicly available

information.

Tests

of Semi-strong Form

Efficiency:

Extensive

academic research supports

the semi-strong version of

the efficient market

hypothesis.

The literature devotes much

more attention to tests of

semi-strong form

efficiency

than to weak form tests. Studies

have investigated the extent

to which people can

profit

by acting on various corporate

announcements such as stock

splits, cash

dividends,

and

stock dividends. While and

occasional research paper

shows that small profits

could

have

been made in a particular

case, the general result is

consistent: The market

reacts to

public

information efficiency, and investors

will seldom outperform the

market averages by

analyzing

public news, especially if

they must pay commissions to

buy and sell.

We

recognize that the market is

pretty efficient. We have

seen time after time

that when we

get

the word that a Wall Street

firm is now recommending a

stock that stock is already

up a

point-and-a-half.

The market is that

efficient. As soon as anyone gets

wind of a firm's

recommendation-boom-people

are buying it, and that

stock's price goes up. By

then, the

value

[of the information] is

diminished.

147

Investment

Analysis & Portfolio Management

(FIN630)

VU

-Michael

J. C. Roth

Executive

Vice President

USAA

Investment Management

In

fact, academic evidence

indicates that active

portfolio managers (those

who frequently

change

their portfolios to include

"better" stocks) tend to

subtract value rather than

add it.

Most

people try to beat the Standard &

Poor's Stock Index by

picking better stocks or

moving

to better sectors of the

market. But studies show it is a

game that

underperforms.

-Leonard

H. Wissner

Chief

Investment Officer

Ward

& Winsser Capital

Management

Researchers

at The Wall Street Journal, in

conjunction with Zack's

Investment Research,

report

that for the 5-year

period ending 30 September 1999

the stock recommendations

of

only

3 of the 15 major brokerage firms

managed to outperform the

205.6 percent earned

by

the

S&P 500 index.7

In the

first nine months of 1998,

88 percent of the actively

managed

U.S.

mutual funds trailed the

performance of the S&P 500.

Most people would expect

that if

anyone

could analyze the market

better than average, the

well-trained, experienced analysts

at

the major investment houses

could. These "experts" did

not do well during this

period.

Their

substandard performance is discouraging

but surprisingly

common.

One

particularly famous study by

Ball and Brown deals with

the market's reaction

to

corporate

earnings announcements.8 This research reported

that stock prices react

favorably

to

better-than-expected earnings, and vice

versa. However, they also reported

that security

prices

seemed to anticipate the

news as much as a year prior

to the announcement, and

that

by

the time the actual

earnings were made public

and investor has little

opportunity to

capitalize

on the news.

Another

noteworthy event study

looked at the market

reaction to the death of a

corporate

chief

executive officer. Interestingly,

market prices declined when

the CEO was a

professional

manager. But when the CEO

was the company founder, the

death was

associated

with an increase in the

stock price. This finding

may mean the market

was

encouraged

about the prospect of a new

"professional" company leader.

Many

investors view stock splits

favorably, as mentioned earlier in

the book. Companies

announce

splits in advance of the actual

split date. Can investors earn

abnormal profits by

buying

shares that are about to

split? Fama is also associated

with the classic study on

this

topic.

The study found several

things. First, companies usually

increase their

dividends

when

they split their shares. If

the firm fails to do so,

the market reacts adversely

to this

preceding

the split, but once the

split is announced they

cease to accrue any further.

To

profit

from the split, investors

would have had to have

bought the shares months in

advance

of

the split date. Once

the split is announced, the

free lunch is gone.

Many

tests of semi-strong form

efficiency use the event

study methodology. In an

event

study,

a phenomenon occurring at a known

point in time, such as a

stock split or the

announcement

of corporate earnings, is designated as

time zero. Two days prior to

the event

is

day "T minus two," while

two days after would be "T

plus two." In the typical

conduct of

an

event study, a researcher

would gather a sample of firms

showing one or more instances

of

the event of interest.

Security returns before and

after the event would be

collected.

Depending

on the researcher's hypothesis, the

data might be collected for

monthly, weekly,

148

Investment

Analysis & Portfolio Management

(FIN630)

VU

daily,

or even intraday returns

how far before the

event and how long after

would also

depend

on the particular study.

Typically, the length of the

before and after periods is

the

same.

Regardless

of the month or year in

which the event occurred,

each stream of returns is

then

"lined

up" so that each company's

event corresponds to day zero.

For instance, the

first

observation

might be a split that

occurred on March 4, 1988.

The second company

might

have

had a split on August 15,

1992. Both of these dates

would be time zero in the

event

study.

In both instances the following

day would be day T plus

one.

3. Strong

Form Efficiency:

The

most extreme version of the

EMH is strong form efficiency.

This version states

that

security

prices fully reflect all public and

private information. In other

words, even

corporate

insiders cannot make abnormal

profits by exploiting their

private; inside

information

about their company. Inside

information is formally called

material, nonpublic

information.

Section

16 of the Securities Exchange

Act of 1934 defines an insider as

"an officer or

director

of a public company, or an individual or

entity owning 10 percent or

more of any

class

of a company's shares." The law

requires insiders to report

their holdings of

corporate

securities

within 10 days of becoming an insider.

They must also report

subsequent

transactions

in these securities for

themselves or a member of their

family by the tenth

day

of

the month following the

trade.

The

evidence does not support

this form of the EMH.

Insiders can make a profit on

their

knowledge,

and every year people go to jail, get

fined, or get suspended from

trading for

doing

so. Inside information gives

an unfair advantage that can be used to

extract millions

of

dollars out of the

marketplace. Where did these

millions in profit come from?

They came

from

the pockets of individual investor

who did not have

access to the

confidential

corporate

news. Society does not

feel this advantage is fair;

consequently, insider trading

is

illegal.

The

Enforcement Division of the

Securities and Exchange Commission is

responsible for

detecting

and prosecuting insider trading

violations. People sometimes believe

they can stay

at

arm's length from the

law by passing the inside

information to a relative, who

passes it to

a

friend, who passes it to

someone else who then

acts upon it to the benefit

of all parties

concerned.

This strategy seldom works

unless the trades are

small. (Investigating

small

potential

violations is not economically

feasible). All brokerage accounts are

computerized,

and it is a

relatively simple matter to

screen for unusual account

activity surrounding

mergers,

important corporate announcements, and

similar events.

The

Insider Trading Sanctions

Act of 1984 permits the

courts to impose civil penalties of

up

to

three times the profit

gained or loss avoided because of the

use of material,

nonpublic

information,

plus it provides for a

criminal fine of up to $100,000. It also

precludes

corporate

officers, directors, and anyone

owning 10 percent or more of a

firm's equity

securities

from making a profit on a purchase and

sale of the company's equity

within a six-

month

period. These people also may not

sell the company's equity

short.

The

Insider Trading and Securities

Fraud Enforcement Act of 1988 is

related legislation.14 It

increased

criminal fines to $1 million,

raised the maximum jail

term to ten years,

and

required

firms involved in the

securities business to implement

programs to prevent

insider

trading

by their employees. The real

teeth of the law comes

from holding a firm liable

if its

149

Investment

Analysis & Portfolio Management

(FIN630)

VU

employees

engage in insider trading, and

providing a 10 percent bounty to

encourage

informants

to come forward.

The

strong form of EMH states

that security prices fully reflect

all relevant public

and

private

information.

Tests

of Strong Form Efficiency:

Strong

form tests are more

difficult to conduct because it

would be hard to do so

without

breaking

the law. We can, however,

find evidence to support the

potential value of

inside

information.

Business

Week publishes a column

called "Inside Wall Street,"

in some respects similar

to

The

Wall Street Journal's "Heard on

the Street" column. Stock

prices often react to news in

these

types of articles, but they

should not react until the

publication hits the streets.

The

magazine

is not released to the

public until 5:15 PM on

Thursdays, so news of stocks

mentioned

in the "Inside Wall Street"

column in not public

information during the

Thursday

trading

day.

Unusual

trading activity in a number of stocks

mentioned in the column over

a period of

five

months led McGraw-Hill; the

publisher of Business Week, to inform

officials at the

Securities

and Exchange Commission as well as at

the exchange.15 Table 9-4 shows

the

suspicious

price movement.

For

seven issues of the magazine

over this period, stocks

mentioned in the article

rose an

average

of 11.54 percent compared to an average

rise of 0.12 percent in the Standard

&

Poor's

500 stock index. The large

Thursday rise and increased trading

volume was

compelling

evidence that someone was

trading ahead of the public

distribution of the

magazine.

This act was illegal trading on

inside information.

The

Semi-Efficient Market

Hypothesis:

The

essence of the semi-efficient

market hypothesis (SEMH), a

cousin to the EMH, is

the

notion

that some stocks are priced

more efficiently than

others. This idea is

appealing to

many

market analysts. Consider

two very different companies

such as IBM and a

hypothetical

start-up firm called

Triple-Scan Video. Everyone

has heard of international

Business

Machines, which trades on

the New York Stock

Exchange and many

regional

exchanges.

Thousands of portfolios contain

its shares, and virtually

all security analysts

watch

it. The likelihood of

realizing an unusual gain in

the shares of IBM is

extremely

small.

The stock is priced fairly,

and investors who buy some

will likely earn a long-term

return

consistent with the stock's

level of risk.

What

about Triple-Scan Video?

According to the SEMH, fewer

people are watching

this

company,

which implies a greater likelihood

these shares will be undervalued. In

other

words,

the stock might not be

priced as efficiently as the

shares of IBM or other

well-known

companies.

This

idea is sometimes used in support of

the thesis that the market

has several tiers.

The

first

tier contains IBM, GM, Exxon, and

other large firms. The

second tier might

contain

lesser-known

but well-established companies such as

those that trade on the

American

Stock

Exchange or the NASDAQ

National Market System. The

third tier might be

companies

such as Triple-Scan Video.

Another tier might be pink

sheet stocks. The

further

down

the tier list an investor

goes, the less efficient

the pricing, or so the

reasoning goes.

150

Investment

Analysis & Portfolio Management

(FIN630)

VU

It is

probably safe to say that

most students of the market

are generally sympathetic to

the

logic

of the semi-efficient market

hypothesis. It is not possible to follow

every security.

Analysts

need to follow the big

names, and simply do not

have time to research the

ever-

expanding

list of emerging companies.

The

essence of the semi-efficient

market hypothesis is the

notion that some stocks

are

priced

more efficiently that

others.

Security

Prices and Random

Walks:

The

efficient market hypothesis

states that the current

stock price fully reflects

relevant

news

information. While some of

the news is expected, much of it is

unexpected. The

unexpected

portion of the news, by

definition, arrives randomly

the essence of the

notion

that

security prices follow a random

walk because of the random

nature of the news.

Some

days

the news is good, some days

it is bad. Specifics of the

news cannot be predicted

with

great

accuracy.

Substantial

uncertainty even surrounds

news that seems reasonably

predictable. An article

in

Forbes reported the result

of a study showing that over

the period 1973-1990, the

average

error

made by security analysts in

forecasting the next

quarter's corporate earnings

for the

firms

they covered was 40 percent. On an

annual basis, the average

error was never less

than

25

percent. From 1985 to 1990,

the average error was 52

percent, indicating that

the

analysts'

forecasting ability had not

improved over the

period.

It is

perfectly possible for analysts to

disagree in an efficient market. As an

example, on

November

30, 1998, the firm

Van Kasper and Company reaffirmed

its "Strong Buy"

recommendation

on Transocean Offshore (RIG,

NYSE). That same day

Janney

Montgomery

Scott changed its recommendation

from "Moderate Buy" to

"Strong Sell."

When

the news relevant to a

particular stock is good, people

adjust their estimates of

future

returns

upwards or they reduce the

discount rate they attach to

these returns. Either way

the

stock

price goes up. Conversely,

when the news is bad,

the stock price goes

down.

Many

people misunderstand what the

random walk idea really

means. It does not say

that

stock

prices move randomly. Rather, it

says that the unexpected

portion of the news

arrives

randomly,

and that stock prices adjust to

the news, whatever it

is.

In a

famous analogy, a drunk

staggers from lamppost to

lamppost with a point of

departure

and a

target destination. The path

of the drunk shows a trend

from one post to the

next.

Along

the way, however, the

path is erratic. The drunk

wanders right and left,

perhaps

occasionally

out into the street or into

a building wall. The precise

route cannot be

predicted.

The same is true of a

security price and its

consequent return. Over the

long run,

security

returns are consistent with

what we expect, given their

level of risk. In the

short

run,

however, many ups and downs

seem to cloud the long-run

outlook. The stock

price

behaviors

shown in the four charts of

Figure 9-2 are random

walks. Each succeeding

observation

is just as likely to be up as

down.

ANOMALIES:

This

section reviews several

important market anomalies

that financial researchers

actively

explore.

In finance, the term anomaly

refers to unexplained results

that deviate from

those

expected

under finance theory,

especially those related to the

efficient market

hypothesis.

Familiar

anomalies include the low PE

effect, the small firm

effect, the neglected

firm

effect,

the January effect, and the

overreaction effect.

151

Investment

Analysis & Portfolio Management

(FIN630)

VU

The

Low PE Effect:

Numerous

academic studies have uncovered

evidence that stocks with

low PEs provides

higher

returns than stocks with

higher PEs. This tendency is

called the low PE effect.

The

studies

show this result even

after accounting for risk

differentials, which seems to be

in

direct

conflict with the capital

asset pricing model and the

theory behind it.

Some

evidence indicates that low PE

stocks outperform higher PE

stocks of similar

risk.

Low-Priced

Stock:

Many

people believe that certain

stock price levels are

either too high or too

low.

Equivalently,

they believe the price of

every stock has an optimum

trading range. By

finance

theory, the stock price

should be merely a marker

and, by itself, be of no value

in

comparing

firms. The size (and value)

of a piece of pie depends on the

number of pieces

into

which the pie is cut.

Still,

folklore surrounds stock prices. As

early as 1936, the academic

literature showed

that

low-priced

common stock tended to earn higher

returns as stock with a high

price. 18

In

the

classic

investment book by Graham and

Dodd, the authors state, "It is a

commonplace of the

market

that an issue will rise more

steadily from 10 to 40 than

from 100 to 400."

Consider

the following question: Is it

easier for a stock to rise

from $5 to $6 than it is for

it

to rise

from $50 to $60? Most people

who play the market

believe it is. If it is the

case

(which

theory and empirical evidence

dispute), then every firm

whose stock sold for

$50

should

split ten for one so that

its share price would

advance faster.

The

Small Firm and Neglected

Firm Effects:

Like

the low PE effect, the

small firm effect and the

neglected firm effect are

two important

market

anomalies that influence the

stock selection of some

investors (and some

portfolio

managers).

The

Small Firm

Effect:

The

small firm effect recognizes

that investing in small

firms (those with low

capitalization)

seems

to, on average; provide superior

risk-adjusted returns. Solid

financial research

supports

this hypothesis. Important

papers on this topic include

those by Reinganum20 and

by

Banz.

The

obvious implication of the

small firm effect is that

portfolio managers should

give

small

firms particular attention in

the security selection

process. We do not know why

the

small

firm effect exists, but it

seems to persist. In the past,

some anomalies tended to

disappear

soon after they were

reported. The small firm

effect is still with

us.

The

Neglected Firm

Effect:

The

neglected firm effect is a

cousin to the small firm

effect and the semi-efficient

market

hypothesis.

Institutional investors are sometimes

limited to larger capitalization

firms. As a

consequence,

security analysts do not pay

as much attention to those firms

that are unlikely

portfolio

candidates. One paper by Arbel,

Carvell, and Strebel investigated 510

firms over a

ten-year

period and found, as expected, that

the smaller firms

outperformed those widely

152

Investment

Analysis & Portfolio Management

(FIN630)

VU

22

held

by institutions. The authors

postulated that institutions

might perceive more risk

with

the

smaller firms, and hence they

ignore them. In a related

paper, Arbel and Strebel

showed

other

evidence that the attention

of security analysts does

affect the way shares

are priced,

and

that if analysts neglect a

firm it has a systematic

impact on the share

value.

The

implication is the same as

with the small firm

effect: Neglected firms seem

to offer

superior

returns with surprising

regularity. When the Arbel,

Carvell, and Strebel paper

was

published

in 1983, the authors closed by

stating that the effect was

"unlikely to persist over

time."

Neglected firms continue to be an

important research area that

we have not yet

figured

out.

Market

Overreaction:

Another

area of current research

interest lies in the observed

tendency for the market

to

overreact

to extreme news, with the

general result that

systematic price reversals

can

sometimes be

predicted. For instance, if stocks

fall dramatically, they have

a tendency to

perform

better than their betas

indicate they should in the

following period. De Bondt

and

Thaler

have written several

important papers dealing

with this subject.

Experimental

psychologists know that people

often rely too heavily on

recent data at the

expense

of the more extensive set of

prior data. At a race track,

for instance the

betting

pattern

on the following race, even

if the handicapper was largely inaccurate

on previous

races.

In their studies, De Bondt and Thaler

found "systematic price

reversals for stocks

that

experience

extreme long-term gains or losses:

Past losers significantly outperform

past

winners."

Brown

and Harlow found that the

overreaction is stronger to bad

news than to good

news

during

the period of their study.

After an especially large

drop, security returns over

the

following

period were unusually large

and persistent.

The

January Effect:

Another

well-known anomaly is called

the January effect. Numerous

studies show

persuasive

evidence that stock returns

are inexplicably high in

January, and that small

firms

do

better than large firms in

January.

In

Richard Roll's Journal of

Portfolio Management study,

the begins by reporting, "For

18

consecutive

years, from 1963 through

1980, average returns of

small firms have been

larger

than

average returns of large

firms on the first trading

day of the calendar year."

Comparing

AMEX stocks,

which are generally smaller

firms, with those on the

NYSE, Roll found

that

the

average return differential was

1.16 percent in favor of the

small firms, and that the

t-

statistic

for significance of the

difference was a whopping

8.18.

Several

explanations of this phenomenon

have been proposed. Branch

proposes that the

superior

January performance comes

from tax loss trading late

in December.27 A better

explanation

is probably provided by Rogalski and

Tinic, who provide evidence

that the risk

of

small stocks is not constant

over the year, and tends to be

especially high early in

the

year.

The reason for this

higher risk phenomenon is

itself unexplained. Kiem

explains this

result

by reporting another anomaly.

For some reason, stocks tend to trade

near the bid price

at

the end of the year and

toward the ask price at

the beginning of the year.

In any event,

January

tends to be a good month for the

stock market.

Some

analysts will argue that this

effect should really be

called the "November

through

January"

effect because these three

months stand out for their

good performance. Time

153

Investment

Analysis & Portfolio Management

(FIN630)

VU

30

magazine

recently reported on a study by

the Hirsch Organization that

shows since 1950

the

S&P 500 index was up an average 1.7

percent in November, 1.8

percent in December,

and

another 1.7 percent in

January. The next best

month was April at 1.4

percent.

(September is

the only month that is

negative, down 0.2 percent

on average.)

Other

studies find evidence of a January

effect in securities other

than common stock.

Chen

documents

the presence of the effect

with high, medium and

speculative grades of

preferred

stock.31 Wilson and Jones do so for

corporate bonds and commercial

paper.32

Gay and

Kim

look

at seasonality in the futures

markets.34

The

January effect is a pervasive

result that

puzzles

many people.

Further,

some people consider the

first five trading days of

January to be a harbinger of

how

stocks will

perform for the rest of the

year. Since 1950 in only three years

(1966, 1973 and

1990)

has the S&P 500 been

higher at the end of the

first week of the year,

but lower by the

end of

the year. Some people refer

to this as the January

indicator to distinguish it from

the

January

effect. It is probably not an

especially useful indicator.

The market is usually up

for

the

year, and the historical

data indicate a bad first

week for the S&P 500

does not predict a

down

year for the

market.

Stock

returns are inexplicably

high in January, and small

firms' stocks do better than

large

firms'

in this month.

The

Weekend Effect:

The

weekend effect is the observed

phenomenon that security

price changes tend to

be

negative

on Mondays and positive on the

other days of the week, with

Friday being the

best

of

all.35 This persistent

result does not yet

have a satisfactory explanation.

Some

behaviorists

claim that people are upbeat on

Fridays, and this attitude

translates into stock

market

optimism. Monday is a down

day in other ways, so it

might as well be a down

day

for

the market, too, or so the

thinking goes. Whatever the

cause, the weekend effect

remains

as

anomaly. Once again,

however, the effect is too

small to be economically

significant.

The

Persistence of Technical

Analysis:

Market

efficiency tests, especially those

dealing with the weak

form; have routinely

found

that

any evidence of market

inefficiency cannot be profitably

exploited after including

the

effects

of transaction costs. Still, an immense

amount of literature is printed

each year based

in

varying degrees on technical

techniques that, if the EMH is

true, should be

useless.

Even

finance professors seem less

than totally committed to

the EMH paradigm. In a

national

survey pf investment professionals, 40

percent of the respondents with a

Ph. D. in

finance

felt that advance-decline

lines (a popular technical

analysis tool) were "useful"

or

"very

useful." One-fourth of the respondents

agreed that "charts enhance

investment

performance."

Needless

to say, we do not fully understand

the theory or practice of

technical analysis.

Its

techniques

are generally imprecise and do

not lend themselves to

rigorous statistical

testing.

Certain

phenomena from the clinical

psychology literature seem to be at least

partially

operative

in the stock market. At a casino

craps table, for instance,

shooters throw the dice

harder

when trying for a high

number. Low numbers, of course,

require an easier toss.

Even

though

no connection can be made between

the random number that

occurs and the

strength

of

the toss, the shooters

experience a psychological illusion of

control. Similarly,

humans

suffer

from hindsight bias. With

trading techniques, people tend to

remember their

154

Investment

Analysis & Portfolio Management

(FIN630)

VU

successes

and displace their failures. One

investor, for example, owned

200 shares of a

common

stock, his only investment.

On days when the stock was up a

point, he would brag,

"I

made $200 today." On days when

the stock was down, he said

nothing. Later, when

the

stock

rose a point again, in his

view he "made another $200."

He made that same

$200

many

times.

Final

Thoughts:

The

U.S capital markets are

informationally and operationally quite

efficient from the

individual

investor's perspective. They

are the envy of much of

the world, and many

developing

second and third world

cultures emulate them.

Portfolio managers, however,

are

hired

and fired largely on the

basis of realized return, and a

few basis points can make

a

significant

difference in the progression of

their careers. Inefficiencies

that may be

economically

insignificant to a retail customer

after considering trading

fees may be much

more

attractive to an institutional

investor.

Eugene

Fama and Kenneth French

recently reported updated research on

the nature of asset

pricing

that may eventually be

helpful in explaining market

anomalies. Expanding on

their

earlier

work, they find "anomalies

largely disappear in a three-factor

model," where

security

prices

are determined by the excess

return on the market

portfolio, the difference

between

the

returns on portfolio of small stocks and

a portfolio of large stocks, and finally

the

difference

between the returns on a

portfolio of high book-to-market stocks

and low book-

to-market

stocks. Importantly, though, they state,

"The three-factor risk-return

relation is,

however,

just a model. It surely does

not explain expected returns on

all securities and

portfolio."

In

sum, much is not yet

known about asset pricing.

The markets are not

perfect. Still, the

vast

number of securities traded on the

exchanges, the rapid introduction of

new financial

products,

and the globalization of world economies

provide a fair, but

complicated financial

battleground.

Summary:

The

efficient market hypothesis

(EMH) relates to informational efficiency

and the fair

pricing

function as opposed to operational

efficiency. The essence of

the EMH is that so

many

people watch the marketplace

that few if any individuals

can consistently make

windfall

profits by picking stocks better

than the next person.

There

are three forms of the

EMH. The weak form

says that past prices, or

charts, are of no

value

in predicting future stock

price performance. The

semi-strong form says that

security

prices

already fully reflect all

relevant publicly available

information. The strong form

of

the

EMH includes private, inside

information as well. Considerable

empirical research

supports

the semi-strong form;

however, we know that

insiders can make illegal

profits.

The

random walk theory does

not state that security

prices move randomly. Rather

it

maintains

that the news arrives

randomly, and that in accordance

with the EMH security

prices

rapidly adjust to this

random arrival of

news.

Anomalies

are occurrences in the

market that are inexplicable

by finance theory. Stocks

with

low PEs tend to show

unusually higher returns;

January is a good month for

the stock

market;

and small firms tend to do

especially well in January.

Technical analysis is

diametrically

opposed to the efficient

market hypothesis, yet it

has many advocates,

including

well-educated finance professors and

practitioners.

155

Table of Contents:

- INTRODUCTION OF INVESTMENT

- THE ROLE OF THE CAPITAL MARKETS

- THE NASDAQ STOCK MARKET

- Blue Chip Stocks, Income Stock, Cyclical Stocks, Defensive Stocks

- MARKET MECHANICS

- FUNDAMENTAL STOCK ANALYSIS

- BEYOND FUNDAMENTAL ANALYSIS

- What is Technical Analysis

- Indicators with Economic Justification

- Dow Theory

- VALUATION PHILOSOPHIES

- Ratio Analysis

- INVESTMENT RATIOS

- Bottom-Up, Top-Down Approach to Fundamental Analysis

- The Industry Life Cycle

- COMPANY ANALYSIS

- Analyzing a Company’s Profitability

- Objective of Financial Statements

- RESEARCH PHILOSPHY

- What Is An Investment Company

- Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs)

- COMMON STOCK: ANALYSIS AND STRATEGY

- THE EFFICIENT MARKET HYPOTHESIS (EMH)

- Behavioral Finance

- MARKET INDEXES

- POPULAR INDEXES

- BOND PRINCIPLES

- BOND PRICING AND RETURNS

- Accrued Interest

- BOND RISKS

- UNDERSTANDING RISK AND RETURN

- TYPES & SOURCES OF RISK

- Measuring Risk

- ANALYZING PORTFOLIO RISK

- Building a Portfolio Using Markowitz Principles

- Capital Market Theory: Assumptions, The Separation Theorem

- Risk-Free Asset, Estimating the SML

- Formulate an Appropriate Investment Policy

- EVALUATION OF INVESTMENT PERFORMANCE

- THE ROLE OF DERIVATIVE ASSETS

- THE FUTURES MARKET

- Using Futures Contracts: Hedgers

- Financial Futures: Short Hedges, Long Hedges

- Risk Management, Risk Transfer, Financial Leverage

- OVERVIEW